Kifu

Kifu ( Japanese 棋譜 ) is the Japanese name for a game notation for a Go or Shogi game. Traditionally, kifu is used to plot a game on a grid diagram.

description

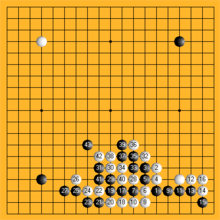

In Go, in contrast to chess, the pieces that are placed remain in the same place throughout the game. A move-by-move notation as in chess notation is therefore not necessary. To note a game, in Kifu only the number of moves in which the stone was placed on the corresponding place is noted in the grid diagram. The notation in Shogi, however, is similar to that in chess.

history

A large inventory - many thousands of games - of kifu records from the Edodynasty have come down to us. A relatively small number was published in book form; good players usually make hand copies of interesting games. This reflects a characteristic of this recording method: large parts of the endgame are often left out, since the reconstruction of the short endgame is routine for strong players. This also explains the transmission of some games in different versions and possible inaccuracies in the endgames.

The early Western Go players found kifu unsatisfactory for a variety of reasons and tried to replace it with the use of algebraic notation to move the stones. However, this did not catch on and almost all Go books and magazines use a variant of Kifu to depict games, variations and problems. While a typical chess publication consists of algebraic notation and occasional diagrams, Go publications mostly consist of diagrams with some sequences of marked moves and a comment in text form.

The rejection of kifu by the first European player Oskar Korschelt came about because Chinese numbers were always used in the early 19th century. The numbering in this way continued until 1945.

Tournament practice

Professional games are often recorded by other professional players who have been assigned for this purpose (not, as is the case with chess game forms, by the opponents themselves). Such recordings are not only interesting in terms of sports reporting , but are also recreated by many Go players in order to learn from them.

Recordings of one's own games are also often analyzed, often with the help of stronger players, who can answer questions to which one could not find an answer during the game, which can draw attention to mistakes or interesting possible variations and point out strengths and weaknesses in one's own style of play .

In amateur tournaments, you can see many participants taking notes on their games on special forms or on pocket computers. Others avoid this as a burden on their time budget and concentration, especially when they are not dependent on it. Players with Dan rank can usually add a game from their head after they have finished and then record it on this occasion.

application

Re-enacting a game that was noted as kifu on a single diagram is still very difficult for beginners as the moves have to be found on the diagram. An advanced player needs about 20 minutes for a full game. A professional would need about ten minutes and could easily see highlights of the game from the kifu. The strong player can easily find the moves in games at his level, as the number of useful possibilities is often not great.

In most games there are a small number of moves on crossing points that were already occupied (this happens e.g. during a Kō fight). Annotations in the margin of the kifu usually give this information in the form 57 on 51 or in a similar way. Match records are often supplemented with information about the strength of the players, the date, the tournament and the venue.

Databases

Many of the major games are now available in machine readable form using a small number of Go file formats. This has many advantages in terms of replayability and archiving of games. However, the general opinion is that replaying it on a real board is better than just on the screen.

copyright

The question of whether a game record is a suitable subject of copyright is judged differently. In Japan, the Association of Japanese Professional Go Players Nihon Kiin is assuming copyright protection. Sponsors do not acquire the rights from individual Go players, but collectively from the association. Internationally, however, copyright protection is by no means recognized. Rather, kifus are widely used on the Internet without first asking for permission.