Mokomokai

Mokomokai (also Toi Moko called) are preserved heads of Maori , the indigenous people of New Zealand , whose faces with Tā moko - tattoos were decorated. They were valuable merchandise during the Musket Wars of the early 19th century.

Moko

Moko face tattoos were a tradition of Māori culture until they began to disappear in the mid-19th century. In the pre-European period they indicated a high social rank. Usually only men wore full face moko, while high-ranking women often had tattoos on their lips and chin.

Moko showed rites of passage for people with the rank of chief as well as important events in their lives. Each moko was unique and contained information about a person's rank, tribe, parentage, occupation, and heroism. Mokos were expensive to make and more elaborate mokos were usually restricted to chiefs and high-ranking warriors. In addition, Maori who designed and made Moko, like Moko himself, were surrounded by taboo and protocol. The tradition has been revived since the middle of the 20th century.

Mokomokai

When someone died with moko, the head was often preserved. The brain and eyes were removed, all openings sealed with kauri resin and fibers from New Zealand flax. The head was boiled or steamed in an oven, then smoked over an open fire and dried in the sun for several days. He was then treated with shark oil . Heads prepared in this way - mokomokai - were kept by the families in carved boxes and only brought out for religious ceremonies.

The heads of enemy chiefs killed in battle were also preserved. These mokomokai were viewed as war trophies, displayed in the marae and mocked. However, they were important in diplomatic negotiations between warring tribes. The return and exchange of Mokomokai were an important prerequisite for a peace agreement.

Musket Wars

In the early 19th century, tribes who had contact with European seamen, traders and settlers were given access to firearms, which gave them a military advantage over their neighbors. Since the other tribes were now also forced to obtain firearms - even for self-defense - the musket wars broke out. During this time of social instability, mokomokai became a commodity that fetched high prices as curiosities, works of art or museum pieces in Europe and America and could be exchanged for firearms and ammunition.

The high demand for firearms led tribes to raid neighbors to find heads for sale. They also tattooed slaves and prisoners (albeit with meaningless motifs and non-traditional moko) in order to be able to deliver. The peak of the moko trade was between 1820 and 1831. In 1831 the governor of New South Wales banned exports from New Zealand. At the same time, the demand for firearms decreased in the 1830s due to market saturation. By the time the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 and New Zealand became a British colony, exports had all but ceased and moko became less common in Māori society. An occasional smaller-scale trade passed on in later years, however.

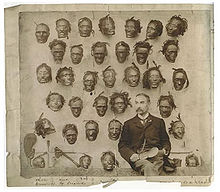

The Robley Collection

Horatio Gordon Robley was a British army officer and artist who served in New Zealand during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s. He was interested in ethnology and fascinated by the art of tattooing. He was a talented illustrator and wrote the work on Moko Moko published in 1896 ; or Maori tattooing . After his return to England he built up a collection of 35-40 Mokomokai, which he later offered to the New Zealand government for sale. When this refused, the American Museum of Natural History acquired most of the collection.

repatriation

Efforts have been made since the beginning of the 21st century to return the hundreds of museum and privately owned Mokomokai to New Zealand. There they should be returned to their relatives or kept in the Museum of New Zealand , but not exhibited. This campaign has had some success so far.

literature

- Horatio Gordon Robley: Moko; or Maori tattooing . Chapman & Hall, London 1896. ( Full text in the New Zealand Electronic Text Collection (NZETC))

- Robert. R. Janes, Gerald T. Conaty: Looking Reality In The Eye: Museums and Social Responsibility . University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta 2005, ISBN 978-1-55238-143-4 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ The heads of the Maori. In: Der Tagesspiegel of October 5, 2012. Accessed January 7, 2019.

- ^ A b c d e Christian Palmer, Mervyn L. Tano: Mokomokai: Commercialization and Desacralization . International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management: Denver 2004. ( PDF ) accessed November 25, 2008. Palmer & Tano (2004), pp. 1-6

- ^ NZETC: Mokomokai: Preserving the past . Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ↑ Janes & Conaty (2005), pp. 156-157.

- ↑ a b Sunday Star Times. January 16, 2008. Anthony Hubbard : "The trade in preserved Maori heads"

- ^ Reuters / One News. November 6, 2003. Maori heads may return home

- ^ French city vows to return Maori head. ; Associated Press, Paris January 4, 2008.