Paikuli inscription

The Paikuli inscription ( Arabic بيكولي, DMG Baikūlī ; Kurdish په يكولي Peykulî ) contains bilingual texts in Parthian and Middle Persian from the Sassanid period and tells of the triumph of the Sassanid king Narseh over his great-nephew Bahram III. The monument originally consisted of an approximately 8.40 m by 12.60 m high tower with inscriptions on two sides and is located in the Paikuli Pass, a few hundred meters west of the village of Barkal in the Iraqi governorate of as-Sulaimaniya . The location marks the place where Narseh is said to have met with his noble supporters and the overthrow of Bahram was decided.

Historical background

Narseh was the youngest son of Shapur I , who was passed over several times in the line of succession. Nonetheless, Narseh apparently served his brother Bahram I and his nephew Bahram II loyally. In 293, however, Narseh rose against his young great-nephew Bahram III with the support of several nobles . , who had recently ascended the throne, and took military action against his rival. At this point, Narseh had already reached an advanced age and could look back on many years of administrative experience. According to the description of the inscription, he had apparently followed the request of several Persian greats who met at the coronation of Bahram III. Had not felt sufficiently taken into account, wanted a more experienced king in the political situation at the time and therefore chose Narseh as the new king. From the short civil war against Bahram III. Narseh emerged victorious and ascended the throne of Persia.

exploration

The monument, called Bot-ḵāna (" temple of idols") by local residents , was discovered by European travelers in the 19th century and was first explored in 1844 by British major and explorer Henry Creswicke Rawlinson . He passed his notes on to Edward Thomas, who published them with extensive comments in 1868. Ernst Herzfeld visited the site in the summer of 1911 and took some impressions of the inscription . He forwarded his drawings and photographs to Carl Friedrich Andreas in Göttingen. In the summer of 1913 he came back and continued his work, this time systematically. He made impressions of 97 blocks, began to arrange the scattered blocks and made the first hypothetical reconstructions. In 1924 he published all of his knowledge about the monument. His reconstruction and reading of the inscriptions were for the most part correct. The researchers Prods Oktor Skjærvø and Helmut Humbach later re-examined the inscription and also published their reading, and from 2006 an Italian team from the University of Florence under Carlo G. Cereti carried out conservation and excavation work in cooperation with the local Kurdish authorities. They discovered 19 previously unknown labeled blocks in the area, which they published in 2014. All labeled blocks are in a museum in Sulaimaniya .

construction

The monument has a square floor plan with a side length of about 8.40 m. Herzfeld could only estimate the height, since the monument had long since collapsed. With a height-to-width ratio of 3: 2, he stated the tower height to be 12.60 m. At the edges were three-quarter pillars that protruded about 12.50 cm. The monument must have been wider, however, since according to Skjærvø and Humbach the Middle Persian text is already 9.30 m wide.

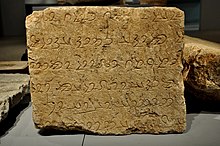

The rectangular monument consists of individual limestone blocks with an average size of 40 × 60 × 40 cm. The interior is filled with a concrete mix of river stones and pebbles, which is held together by plaster as a binding agent instead of cement. The outer blocks were only loosely connected to the filler material, which Herzfeld referred to as a "sloppy technique". The individual blocks show two holes a few centimeters deep on their upper side, in which were located metal clips that held the blocks together. Some of the blocks are labeled while most of the blocks have a smooth outer surface. The limestone was probably extracted directly from the area. On all four upper edges of the pages there were busts of Narseh, which are still preserved.

Due to the location in a valley, strong, sandy winds occur that grind the stones down. In addition to these grinding marks, many blocks are colonized with fungi or bacterial colonies.

text

Two sides of the tower were labeled: the western side contained the Middle Persian text and the eastern wall opposite the Parthian text. The deciphered text consists of an introduction, main part and conclusion. The main part describes three events. The events up to the meeting of Narseh with the nobles, the defeat of Bahram III. and the negotiations between Narseh and the nobles over the future of the empire and the accession to the throne. It goes without saying that the text reflects the victor's, Narseh, view of the conflict. The content can be summarized as follows:

1 Introduction:

Narseh's genealogy is reproduced.

2. main part:

Narseh's nephew and reigning King Bahram II dies. Without Narseh's knowledge, Bahram's son becomes Bahram III. new king. A group of nobles asks Narseh if he could return from Armenia to defeat the usurper and take his rightful place on the throne. Narseh sets out and meets the nobles at Paikuli. Bahram III pulls against his uncle and both sides mobilize their allies. But in the end Bahram III succumbs. and is punished. After his victory, Narseh has a congregation of nobles choose the appropriate king. The choice falls on Narseh, who accepts.

3rd degree:

Narseh pacifies the country and also makes peace with the Roman Empire . Then follows a list of all the rulers who recognize Narseh as King of Kings.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Herzfeld, p. 23

- ↑ On Narseh see the remarks by Ursula Weber: Narseh, King of the Kings of Ērān and Anērān. In: Iranica Antiqua 47 (2012), pp. 153–302, which Narseh does not regard as a usurper.

- ↑ Skjærvø et Humbach 1978, 1980, 1983

- ↑ Cereti et Terribili, 2014

- ↑ Herzfeld, p. 23

- ↑ Herzfeld, p. 24

- ↑ Skjærvø et Humbach, Part 2, p. 10

- ↑ Herzfeld, p. 24

- ↑ Skjærvø et Humbach, Part 3.1; Pp. 3-5

literature

- Ernst Herzfeld : The recording of the Sassanid monument of Paikūli. APAW, born 1914, phil.-hist. Kl., No.1, Berlin 1914

- Prods Oktor Skjærvø and Helmut Humbach: The Sassanian Inscription of Paikuli- Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag Wiesbaden

- Part 1: Supplement to Herzfeld's Paikuli. Munich 1978, ISBN 9783882260182

- Part 2: Synoptic Tables. Munich 1980, ISBN 9783882260823

- Part 3.1: Restored Text and Translation. Part 3.2. Commentary. Munich 1983, ISBN 9783882261561

- Carlo G. Cereti and Gianfilippo Terribili: The Middle Persian and Parthian Inscriptions on the Paikuli Tower. In: Iranica Antiqua 49, 2014, pp. 347-412, doi : 10.2143 / IA.49.0.3009246

Web links

- Herzfeld and the Paikuli Inscription . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica (English, including references)

- The Sassanian Inscription of Paikuli, Part 3 by Prods Oktor Skjærvø and Helmut Humbach

- Digitized edition of Ernst Herzfeld's work , 1924 in English

- The Paikuli project , website about the Italian-Kurdish excavations

- 2006 excavation report

- Photos for Paikuli from the Smithsonian Institution database

Coordinates: 35 ° 6 ′ 2 ″ N , 45 ° 34 ′ 59 ″ E