Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913

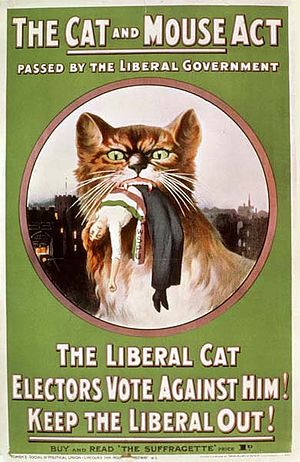

The Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act , commonly known as the Cat and Mouse Act , was a law of the British Parliament passed in Britain in 1913 under the government of Herbert Henry Asquith . Some members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU, commonly known as suffragettes ) had been jailed for vandalism in support of women's suffrage. Some of the suffragettes went on hunger strikes to protest the detention . The hunger strikers were then force-fed by prison staff , which caused a public outcry. The law was a response to the riot and allowed inmates to be released temporarily if the hunger strike affected their health. They were then given a predetermined period of time to recover, after which they were arrested again and taken back to prison to serve the remainder of their sentences. The prisoners could be made subject to conditions during their release. One effect of the law was to de facto legalize hunger strikes. The law's nickname originated from the domestic cat's habit of playing with a mouse so that it can temporarily escape a few times before it is killed.

Application by the government

After the law was passed, force-feeding was no longer used to fight hunger strikes. Instead, the suffragettes on hunger strike were held in prison until they became extremely weak and then released to recover. This allowed the government to claim that any suffering (or even death) resulting from the debilitation from starvation was entirely the fault of the suffragette. During the recovery period, any wrongdoing on the part of the suffragette took them straight back to prison.

background

In order to achieve equal voting rights as men, the WSPU (Women's Social and Political Union, colloquially known as the Suffragettes) took part in protests such as breaking windows, setting fire to police officers, and attacking police officers, but without causing them any harm. Many WSPU members were jailed for these crimes. In response to what they saw as brutal punishment and harsh treatment by the government, the detained WSPU members began an ongoing hunger strike campaign. Some women were released during this operation, but that made the policy of detaining suffragettes pointless. The prison authorities then began force-feeding hunger strikers through a nasogastric tube . Repeated use of this practice often caused illnesses that served the WSPU's goal of demonstrating the government's harsh treatment of prisoners.

Given the growing public concern about the force-feeding and the determination of the detained suffragettes to continue their hunger strikes, the government rushed parliament to pass the law. The law allowed the prisoners to be released so they could recover from hunger strike, while the police had the option to re-arrest the perpetrators after they recovered. The law was intended to counteract hunger strike tactics and the decline in government support from (male) voters for force-feeding female prisoners. Instead, it reduced, if any, support for the Liberal Party government .

Force-feeding reporting women

In the book Suffrage and the Pankhursts , Jane Marcus argues that force-feeding was the main image of the women's election movement in public imagination. Women wrote about how they felt about them in letters, diaries, speeches and publications from the women's suffrage movement , including Votes for Women and The Suffragette . One of the force-fed suffragettes, Lady Constance Lytton , noted in her memory book that working class women were more likely to be force-fed in prison than upper class women. In general, the medical practice of force-feeding has been described as a physical and mental injury that caused pain, suffering, emotional distress, humiliation, fear, and anger.

Violet Bland , too, wrote about her experience of force-feeding in Votes for Women , stating that "they twisted my neck, held my head back, held my throat, and I was held in a vice the entire time" while they tried to shut Bland feed. She wrote that the guards were always six or seven and that “there was really no way the victim could protest much except verbally to express his horror at this; thus no excuse for the brutality that has been shown on several occasions ”. When she did not get up from her chair quickly enough at the end of the assault because she was "helpless and breathless," they grabbed the chair from under her and tossed her on the floor. She had no doubt that the attacks were made with the intent to break the hunger strikers.

Unintended consequences

The ineffectiveness of the law very quickly became apparent as the authorities had much more difficulty than expected in getting the released hunger strikers back into custody. Many of them evaded arrest with the help of a network of suffragette sympathizers and an all-female team of bodyguards who used tactics of deception, cunning and the occasional face-to-face confrontation with the police. One of the first suffragettes to be released on the basis of this law, Elsie Duval , fled abroad. The government's inability to apprehend notable suffragettes turned what was meant to be a discreet means of controlling the hunger strikers into a public scandal.

This law aimed to suppress the power of the organization by demoralizing the activists, but was found to be counterproductive as it undermined the moral authority of the government. The law was seen as a violation of basic human rights, not just of suffragettes but of other prisoners as well. The law's nickname, the Cat and Mouse Act, which refers to the way the government appeared to play with the prisoners as a cat does with a captured mouse, underscored the cruelty of repeated discharges and recurring Imprisonment turned the suffragettes from despised to popular figures.

The implementation of the law by the Asquith government led the militant WSPU and the suffragettes to view Asquith as an enemy to be defeated in what the organization viewed as war. A related effect of this law was to increase support for the Labor Party , many of its founders who supported women's suffrage. For example, the philosopher Bertrand Russell left the Liberal Party and wrote leaflets denouncing the law and the Liberals for making what he believed to be an illiberal and unconstitutional law. So the controversy helped accelerate the decline in the Liberals' electoral position as segments of the middle class began to overflow with Labor.

The law also gave the WSPU a motive to fight and mobilize against other sections of the British establishment - particularly the Anglican Church . During 1913 the WSPU attacked the Bishop of Winchester, Edward Talbot, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson , the Bishop of London, Arthur Winnington-Ingram , the Archbishop of York, Cosmo Gordon Lang , and the Bishops of Croydon , Lewes , Islington and Stepney . Each of them was besieged by delegations in their respective official residences until an audience was granted at which church leaders were invited to protest the force-feeding. Norah Dacre Fox headed many of these delegations on behalf of the WSPU, which are detailed in The Suffragette . In connection with allegations that female prisoners were poisoned while being force-fed, the Bishop of London was persuaded to visit Holloway Prison in person. He made several visits to the prison but it did not work, and his public statements that he could find no evidence of force-feeding abuse - he even believed that force-feeding was carried out "in a benevolent spirit" - were backed by the WSPU viewed as a collaboration with the government and prison authorities. If the WSPU hoped to win the support of the Church for its further goals through the issue of force-feeding, it was disappointed. The church resolved not to be drawn into a fight between the WSPU and the authorities, maintaining the position that militancy is a cause of force-feeding and that since militancy is against the will of God, the church cannot act against force-feeding.

Research suggests that the law did little to deter suffragettes from their activities. Their militant actions did not stop until the outbreak of World War I and their support for the war effort. However, the start of the war in August 1914 and the end of all suffragette activity for the duration of the war meant that the possible effects of the Cat and Mouse Act will never be fully known.

See also

Web links

- How the act politicized the penal system

- Further Cat and Mouse Act Information

- 1913 Cat and Mouse Act

Individual evidence

- ↑ Manchester Guardian , Aug. 24, 1912, p. 6

- ^ Cat and Mouse Act first page. Retrieved September 2, 2018 .

- ↑ June Purvis: Emmeline Pankhurst - A Biography . Taylor & Francis Ltd, London, p. 134 .

- ^ Votes for Women newspaper , July 5, 1912 issue

- ↑ Rachel Williams: Edith Garrud: A public vote for the suffragette who taught martial arts. The Guardian, June 25, 2012

- ↑ Elizabeth Crawford: The Women's Suffrage Movement. A Reference Guide 1866-1928 . Routledge, London 2000, ISBN 978-0-415-23926-4 , pp. 179-180 .

- ^ Paula Bartley: Emmeline Pankhurst . Ed .: Routledge. London [u. a.] 2002, ISBN 978-0-415-20651-8 , pp. 132 .

- ↑ Angela McPherson: Mosley's Old Suffragette - A Biography of Norah Elam . 2011, ISBN 978-1-4466-9967-6 (English, archive.org [accessed September 15, 2015]).