Quem quaeritis trope

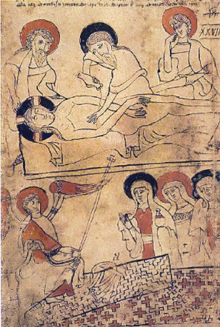

The Quem quaeritis trope (also Visitatio sepulchri: 'Visit to the Grave') is the first dialogical text that has been handed down in the context of the medieval liturgy , a question-and-answer game between angels and mourning women (sometimes called Mary ) at the empty tomb of Christ. Presumably it was sung antiphonally in the service, i.e. by dividing the singers in two halves. It is considered to be the nucleus of medieval theater .

With the words Quem quaeritis ( Latin: 'Who are you looking for?') Begins a newly composed addition ( trope ) to the introitus of the Easter mass . It appears for the first time in a manuscript of the St. Gallen monastery from the 10th century , spreads over the whole of Europe in the following years and is expanded in later versions to include extensive spiritual games , later to mystery games in the urban public (e.g. . in the Muri Easter play , 1250).

text

-

Interrogation. Quem quaeritis in sepulchro, o Christicolae?

-

Responsio. Jesum Nazarenum crucifixum, o caelicolae.

- Angeli. Not est hic. Surrexit, sicut praedixerat. Ite, nuntiate, quia surrexit de sepulchro.

-

Question: Who are you looking for in the grave, you followers of Christ?

-

Answer: Jesus of Nazareth, the crucified, you heavenly messengers.

- Angel: He's not here. He was resurrected just as he foretold. Go and announce that he is resurrected from the grave.

-

Question: Who are you looking for in the grave, you followers of Christ?

meaning

The salvation event is not only told here, but the acting figures speak up themselves. This is a break with the biblical and liturgical custom ( influenced by Neoplatonism ) that only narration should be given, but the narrative should not be visualized in dialogue (saying instead of showing). As a question in direct speech is Quem quaeritis? only handed down in the non-liturgical Gospel of Peter .

In the Regularis Concordia of the Benedictine monks of Winchester around 970, stage directions for the sung text are preserved, which show that the trope was actually staged in the manner of a small play. Three figures detach themselves from the choir of the monks and walk towards the altar towards an "angel" who gives them the message of the resurrection of Christ . In these instructions, the remaining garment of Christ is added to the conquered cross (which he would have taken with him had he gone away alive). The relics prove both the absence and omnipresence of Christ, so they are not traces in the criminalistic sense.

The misleading impression from a medieval perspective that the actors and spectators saw themselves transferred directly to the grave is balanced and justified by the message of the disappearance of Christ without a trace. The statement of the angels must be believed without evidence that could be secured on site that would make belief into knowledge.

Only the lack of the essential can be shown. At its core, this is already the medieval vanitas rhetoric: By warning against the nullity of showing, showing becomes legitimate. This paradoxical justification for showing becomes important for its emancipation in European media history .

Whether the defense of mimesis by Aristotle has been taken in the 10th century note can only speculate. There is evidence of an influence from the Eastern Churches at that time , in which ancient theater traditions were more likely than in the West. Certainly, the increased importance of the public and representativeness in the course of the enlargement of monasteries and cities contributed to the upgrading of the display at the time.

literature

- Nils Holger Petersen: Les textes polyvalents du Quem quaeritis à Winchester au Xe siècle. In: Revue de musicologie. Vol. 86, 2000, ISSN 0035-1601 , pp. 105-118.

Individual evidence

- ↑ John Gassner (Ed.): Medieval and Tudor Drama. Applause, New York NY 1987, ISBN 0-936839-84-8 , pp. 37f.