Battle of Isandhlwana

Coordinates: 28 ° 21 ′ 32 ″ S , 30 ° 39 ′ 9 ″ E

| date | January 22, 1879 |

|---|---|

| place | Isandhlwana |

| output | Victory of the Zulu |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 1,800 men | over 20,000 men |

| losses | |

|

1,329 dead |

around 1,000 dead, 2,000 injured (estimate) |

Isandhlwana - Nyezane - Rorke's Drift - Ntombe - Hlobane - Kambula - Gingindlovu - Ulundi

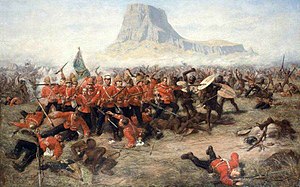

The Battle of Isandhlwana was the first and at the same time one of the largest battles in the Zulu War (1879) between the British Empire and the Zulu State. A force of more than 20,000 Zulu defeated a much smaller British division, which was completely wiped out.

The way to Isandhlwana

The British Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford had crossed the border to Zululand from Natal in Britain with around 5,000 regular troops and 8,000 auxiliary troops at the beginning of January 1879 . The British Army was organized in five divisions that penetrated the Zulu area in three columns. Chelmsford himself commanded the middle of the three departments. It consisted of five companies of the 1st Battalion of the 24th Foot , one company of the 2nd Battalion of this regiment, two cannons, two rocket launchers, 800 men from African auxiliaries and 104 men from a volunteer militia. Chelmsford made camp at Isandhlwana after crossing the border river. King Cetshwayo had sent the main Zulu army against him . This was commanded by Ntshingwayo Khoza , to whom, due to his age, Mavumengwana kaNdlela , one of Ndlela kaSompisi's sons , had been assigned, so to speak , as a “junior commander”.

The battle

Since Chelmsford had little cavalry and refused to use local auxiliaries as scouts, the main Zulu army, which was already nearby, was not identified. Isandhlwana was also only intended as a short stop on the way to the Zulu capital Ulundi , and so Chelmsford also - contrary to the usual practice of the British Army - refrained from fortifying the camp. On January 21, he received news of the Zulu troop movements and on the morning of the 22nd decided to advance with one of his two battalions for reconnaissance in the hilly terrain. However, the Zulu sighted were only weak forces that were not part of the main army and quickly retreated as the British approached. The second battalion, reinforced by an enlisted cavalry division ( Natal Native Horse ) and local auxiliaries from the Natal Native Contingent under Colonel Anthony Durnford , was to guard the camp. The camp was commanded by Brevet Colonel Henry Pulleine. In fact, however, the total strength of the Zulu Army was much closer to the camp than Chelmsford assumed.

When the battle broke out around noon on January 22nd, he was too far away to be able to intervene, and he mistakenly interpreted the noise of the battle as target practice. The 1,800 soldiers left behind faced a Zulu force that was more than ten times as strong. Disagreements about the command structure between Pulleine and Durnford also had a negative impact on the defense of the camp. Although Durnford was in rank above Pulleine, he had no clear order to take command of the camp. He therefore set out with his troops in pursuit of smaller Zulu units. At the time of the main attack, he was therefore about two kilometers from the camp. In addition, Pulleine, an administrative officer with no combat experience, had made no preparations to defend the camp, especially since he was unaware of the danger of attack. The British were therefore in a nearly two-kilometer rifle line when the Zulu attacked in full combat formation . The regular troops were able to repel the onslaught of the Zulu for a while with their aimed fire, while parts of the auxiliary troops quickly fled for lack of rifles. The British then withdrew in the direction of the camp when the ammunition shortage began, but were partly bypassed, partly overtaken by the Zulu and cut down in a scuffle between spear and bayonet . When Chelmsford returned at nightfall, he found a field of corpses. More than 1,300 defenders had died, while some 1,000 Zulu warriors paid with their lives for the attack and an estimated 2,000 others were wounded.

aftermath

In retrospect, Chelmsford blamed Durnford for the lost battle, as Durnford had been ordered to stay in the camp instead of pursuing the Zulu. Since both Durnford and Pulleine had died in the battle, they could not comment on this. All that has been preserved is an order that instructed Durnford to come to the camp . This also disregards factors such as a lack of clarification and the failure to fortify the camp, which were certainly within Chelmsford's sphere of influence.

Interest in the campaign was aroused in the British public by the defeat and the ensuing battle for Rorke's Drift . The British government, which had not supported the project until then, changed its mind and sent more troops to reinforce it.

The further campaign

King Cetshwayo did not use the victory at Isandhlwana to counterattack Natal. The battle was a catastrophic defeat for the British and forced them to break off their invasion of Zululand for the time being; but ultimately it could not change the outcome of the war. The victory of the Zulu against the better equipped and well-trained British troops was bought at a high price and could be compensated for by reinforcements within a few months. On the same day, in the battle for Rorke's drift, 139 British were able to withstand the attack of around 4,000 Zulu of the uNdi corps under Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande. In the summer Lord Chelmsford began to restructure his troops. The British sent troops from across the Empire to South Africa during this period . Lieutenant General Garnet Joseph Wolseley was sent to South Africa to replace Lord Chelmsford. Chelmsford sought a decision on July 4th in the battle of Ulundi and destroyed the Zulu army.

The battle of Isandhlwana is remembered as one of the worst defeats for a British field division.

The events of the Battle of Isandhlwana were filmed in the 1978 film The Final Offensive with Peter O'Toole in the role of Lord Chelmsford and Burt Lancaster as Colonel Durnford.

literature

- William Clive: The Tune That They Play . Macmillan, London 1973, ISBN 0-7221-2428-7 .

- According to Col. Mike Snook: How Can Man Die Better? The Secrets Of Isandlwana Revealed . Greenhill Books, London 2005, ISBN 1-85367-656-X .

- Kingston WHG: Blow the Bugle, Draw the Sword. The Wars, Campaigns, Regiments and Soldiers of the British and Indian Armies in the Victorian Era. Leonaur, Driffield 2007, ISBN 978-1-84677-266-5 .

Web links

- Description at rorkesdriftvc.com (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hamilton Wende: Isandlwana: The defeat that stunned Victorian Britain. BBC News, January 25, 2014, accessed January 25, 2014 .

- ↑ Kingston: Blow the Bugle p. 289