Six children's pieces for the pianoforte

The Six Children's Pieces for the Pianoforte op. 72 ( MWV U 171, U 170, U 164, U 169, U 166, U 168) are almost the only evidence of music composed by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy especially for children . In 1846 the composer prepared the piano pieces from 1842, which are close to the Lieder without words , for publication with the last work number 72, which he himself assigned. The children's pieces, however, only appeared after Mendelssohn's death in December 1847. With the children's pieces, Mendelssohn proves to be an important composer for children too. However, his approach to music for children differs from that of many contemporary and subsequent composers, especially Robert Schumann .

Creation of the children's pieces

During his seventh stay in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from late May to mid-July 1842, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy and his wife Cécil lived with their aunt Henriette Benecke in London. At the time, the Benecke family had seven children between the ages of one and fourteen. The unnamed author of an article on the composer's 100th birthday in The Musical Times cites a member of the Benecke family in his report:

“He [Mendelssohn] felt drawn to the children, nothing gave him more pleasure than romping around with Benecke's boys and girls - who, as adults, had the best memories of this happy time of their childhood. ... He composed the 'Kinderstücke' op. 72 for the Benecke children. Although known as 'Christmas Pieces' in England, they were written into children's albums in Denmark Hill [a London borough] during the summer days of 1842. ... "

In connection with the Six Children's Pieces, two more pieces were created, which Mendelssohn did not include in op. 72 (MWV U 165, U 167). These “two more children's pieces” were first published in 1969 and 2009, respectively. A piano piece written on the farewell day (July 11, 1842), the “Bärentanz”, whose title alludes jokingly to the gooseberries in the Beneckes' garden popular with the children and Mendelssohn, has not yet appeared in print (MWV U 174).

Piano music for children in the mid-19th century

In the 18th century , which was shaped by the Enlightenment , a new understanding of the child developed. Childhood was no longer understood as the sum of deficits that had to be remedied by adulthood, but as a precious, indispensable and independent part of life. “Nature wants children to be children before they become men. If we reverse this order, we get precocious fruits that are neither ripe nor tasty and soon rot: we have young scholars and old children. Childhood has its own way of seeing, thinking and feeling, and nothing is more unreasonable than trying to attribute our way to it. ”( Rousseau ) Christian Felix Weisse (who is considered the founder of German children's literature), Johann Adam Hiller (who is regarded as the "nursery rhyme father") and many others tried very much in this sense to a childhood appropriate literature and music. For the first time in this “pedagogical” century, several works specially developed for music and instrumental lessons appeared. The turn to children continued increasingly in the 19th century . Until 1847, Eicker z. B. 50 collections of piano pieces that are addressed to children or related to the theme of childhood. By the end of the century the number grows exponentially to 743. Many of these works are now forgotten. The publication of 29 German-language piano schools is documented for the period from 1802 to 1847 . The outstanding importance of the piano and the piano literature written for children is undoubtedly related to the strengthening of the middle class. Children playing the piano were particularly obvious evidence of wealth and education. Robert Schumann's piano music for children was and is z. Even today as a standard (often as the sole standard) for piano music aimed at children. Schumann writes about his work on the album for the youth : "I felt as if I were starting all over again." As with many other composers, his pieces for children differ significantly from the other piano compositions. Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy takes a decidedly different path.

Mendelssohn's personal style and the children's pieces

In the children's pieces, the composer takes up the style of composition developed in his songs without words. Six piano pieces are summarized in each of the songs without words - also in op. 72. The children's pieces can be assigned to the types of movements described by Christa Jost for songs without words. The first and third pieces of the children's songs can be seen in connection with the so-called “choir songs” - short, chordal piano movements in which choral singing is alluded to. The second children's piece belongs to the group of "introductory pieces", the first pieces in the booklets of the songs without a word. These pieces were considered to be the epitome of the intimacy of expression associated with the songs without words and are at a slow pace. The melody played around by accompanying figures dominates the piano setting. The fourth children's piece has a relationship with songs without words, the special feature of which is the “follow-up accompaniment” in the middle register. The accompanying voices often follow the melody at a distance of one sixteenth, the tempo and tone of voice of these songs without words can be very different. Like numbers 1 and 3, the fifth piece can be seen in relation to the “choral songs” because of the chordal accompaniment, but also in relation to the so-called “agitato pieces” because of the very fast tempo. The sixth children's piece undoubtedly belongs to this group of virtuoso piano music. A group of pieces that Mendelssohn usually provided with headings in the songs without words is not represented. In particular, a piano piece comparable to the Venetian Gondola Songs is not included in op. 72. Missing headlines are an obvious difference to Robert Schumann's Album für die Jugend . Schumann endeavored to clarify his intention to make a statement in addition to the titles with illustrative drawings. The arrangement of the Children's Pieces op. 72 can be related to the two-part arrangement of the piano pieces often preferred by Mendelssohn from volume 4 (op. 53) - e.g. B. slow-fast or even-odd. In contrast to op. 53, 62 and 67, the children's pieces do not begin in the Andante, but in the Allegro. One could interpret: the adults assure themselves of their calm and equilibrium in the first pieces of the songs without words, the children assure themselves of their impetuousness in the first children's piece. Such an impression can be reinforced by the Vivace ending of op. 72. Similar to the songs without words from op. 53 onwards, the children's pieces are also linked by a key plan, in the center of which is the C minor, which is not the basic key. In the children's pieces there is also clear evidence of Mendelssohn's way of composing outside of the songs without words or outside of the piano music. This includes, in particular, avoiding contrasting themes, instead creating melodic, rhythmic or metrical similarities between the limbs. The various melodic sections, but also the accompanying voices, are interwoven through combination, variation, sequence, spinning or differentiation. Despite constant change, this often gives the impression of hearing familiar things, of being “at home”. In many of Mendelssohn's compositions, the melody is particularly prominent. The expression of a song melos - also in instrumental works - reinforces an already existing tendency towards repetition.

The Children's Pieces op.72

Basic information on the six children's pieces is given in the following overview:

| No. 1 in G major | ||

| No. 2 in E flat major | ||

| No. 3 in G major | ||

| No. 4 in D major | ||

| No. 5, G minor | ||

| No. 6 in F major |

Mendelssohn connects the six children's pieces with each other in terms of motifs. In this way, the compositional principle of creating melodic, rhythmic or metrical similarities is carried beyond the boundaries of the individual composition.

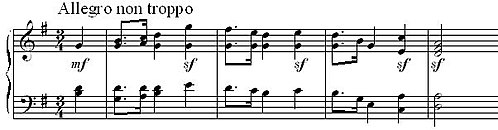

The first children's piece

The first children's piece comprises 44 bars. Two eight-bar groups open the piece and present two motifs that determine the further events in the following pieces. The first motif - it would be easy to sing in a slightly lower register - is based on an upward melody oriented towards the triad. The prelude and the dotted rhythm on the first beat determine almost the entire course of the piece. The melody almost completely fills the octave space with relatively small tone jumps and tone steps in the opposite direction - except for a ', which is only reached in bar 4 with the dominant closure.

| Measures 1 to 4, a1 |

In the following four bars, the downward-pointing melody part of a1 is repeated and changed to the tonic closure.

| Bars 4 to 8, a2 |

This melody contains a downward six-note series from h ′ to d ′. Their reversal is the basis of the second motif with which the following eight bar group begins. Rhythmically, this motif takes over the prelude and the dotted rhythm of bar 1, but then continues in a different way.

| Bars 8 to 12, b1 |

The following section, consisting of 12 bars, begins with a melody derived from the previous motifs, which is varied and has a final effect at the end.

| Bars 16 to 20, c1 |

But before a downward movement guided by the right and left hand reaches a conclusion in bars 27 and 28, the last section, consisting of 16 bars, begins in bar 28, with an almost literal repetition of the first eight bars of the piece. The movement of a2 is picked up by the left hand in a further four-bar group a3 (bars 36 to 40) and carried out into the aftermath (bars 41 to 44). The scale already known from bars 27 and 28 dominates here - but now upwards. The piece fades away with soft chords. The shape could be shown in an overview like this:

| part | A1 | B. | C. | A2 |

| Bars | 8th | 8th | 12 | 16 |

| Four-stroke groups | a1, a2 | b1, b2 | c1, c2, c3 | a1, a2, a3, c4 |

| Remarks | c3 as sequel 1 | c4 as sequel 2 |

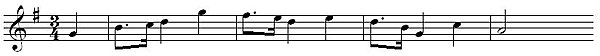

The second children's piece

The second children's piece is the only one with a 4-measure prelude and epilogue. The sequence of notes at the beginning of the first four bar group corresponds completely to the opening motif of the first children's piece (without a prelude).

| Bars 4 to 8, a |

The following group begins like a, but extends further. So the way back to the tonic tone is further. It seems like a reflection of the further melodic path that the form is stretched by two bars compared to a.

| Bars 8 to 14, b |

In sections a and b, the main harmonic functions and the parallels between the tonic and subdominant can be heard, a ends in the dominant, b in the tonic. As a rule, the harmonious change takes place on each quarter, adapted to the calm melody. The melody in measure 9, which is more extensive than at the beginning, is harmoniously marked by the double dominant. The third group expands the upwardly directed series of notes at the beginning by f1 and by the a1 pushed between a flat 1 and b1. This chromaticism is found again at the beginning of the fourth children's piece. The stretching of the initial notes also causes a formal expansion. The climax in the melody is now at the end of bar 15, actually only at the beginning of bar 16. The harmonic course is also expanded, a temporary change to B flat major and the double dominants indicate this.

| Bars 14 to 18, c |

In the following part the downward fourths from part b are taken up melodically.

| Measures 18 to 22, i.e. |

The beginning of section e appears new, yet familiar. Already in c the upswing began with f1, a note repetition in a similar context could already be heard in bar 6, and in bar 23 the rhythmic sequence is similar to bars 5 and 9. Still, activate two upward fourths and a third downward.

| Bars 22 to 26, e |

In bars 6 to 8 and 20 to 22 a certain pause was discernible. In the following sections these figures are taken up, but enhanced by variation (including four additional bars) so that instead of calming down they lead to a climax - harmoniously emphasized by a diminished seventh chord and excessive fifth sixth chord in bar 32. At this point there follows, unique in the children's pieces, an instrumental recitative that merges into the aftermath.

| Bars 34 to 38, recitative |

The second children's piece impresses with its “interweaving” rich in relationships, which also includes the formal and harmonious processes. Mendelssohn creates a wonderfully “poetic” soundscape that is immediately familiar to the listener. The shape of the second children's piece can be represented as follows:

| foreplay | A. | B. | C. | recitative | Aftermath | |

| Bars from-to | 1-4 | 4-14 | 14-22 | 22-34 | 34-38 | 38-42 |

| Parts | a, b | c, d | e, f, g | |||

| Bars (total) | 4th | 4, 6 | 4, 4 | 4, 4, 4 | 4th | 4th |

The third children's piece

The third children's piece is the shortest and simply built with 36 bars.

| part | A1 | B. | A2 | C. |

| Bars | 8th | 8th | 8th | 8 + 4 |

| Four-stroke groups | a1, a2 | b1, b2 | a1, a3 | c1, c2, c3 |

In the first motif of the piece, references to the initial motif of children's piece 1 are clearly recognizable. This relates both to the triad structure and to the downward melody in the second part.

| Measures 1 to 4, a1 |

The second motif turns out to be a derivation from a1. The sixteenths of the first measure have been moved forward by one basic beat and are connected to the downward-leading tone steps beginning in measure 2 (a1).

| Bars 8 to 12, b1 |

The third motif, characterized by the tone repetition, obviously has a relation to ostinato-like tone repetitions in children's piece 1 (g1 - lower part of the right hand in bars 1 to 3), but also in children's piece 3 (e.g. d1 - lower part of the right Hand in bars 9 to 11). The section clearly refers to Mendelssohn's compositional technique, in which accompanying figures can also be given thematic significance.

| Bars 24 to 28, c1 |

The fourth children's play

The fourth children's piece comprises 44 bars. The first motif, derived from the first motif of the first children's piece, takes up the triad structure that dominates at the beginning, but not in the melody. The first and second triad tone sound in the accompaniment. The rise to the fifth is also colored by chromatics.

| Bars 1 to 5, a1 |

The second motif is derived from measures 2 and 3 of motif a1:

| Bars 17 to 21, b1 |

The piece begins with the accompanying figure, which is significant in terms of motif. However, the upbeat motif does not begin until the end of the first measure, so that the accompanying figure almost looks like a prelude (see sound and note example above - No. 4 beginning). This meeting is repeated similarly at the beginning of each four-bar group. Motif and form are interrelated, at the end the incomplete prelude and the shortened aftermath complement each other to form a four-bar group. The form could be represented as follows (the same designations do not necessarily mean identity):

| part | A1 | A2 | B1 | A3 | B2 | Aftermath |

| Bars | 8th | 8th | 8th | 8th | 8th | 4th |

| Four-stroke groups | a1, a2 | a1, a3 | b1, b2 | a1, a3 | b3, a4 | c |

The fifth children's play

The fifth children's piece is relatively extensive with 65 bars and has a richly structured form. The piece can be divided into three larger parts (the same names do not necessarily mean identity).

| part One | a1, 4 bars | a2, 4 bars | b1, 4 bars | b2, 4 bars | b3, 5 bars |

| Part II | a1, 4 bars | a2, 4 bars | b4, 4 bars | b5, 4 bars | b6, 7 bars |

| Part III | a1, 4 bars | a2, 4 bars | a3, 4 bars | a4, 4 bars | a5, 5 bars |

The beginning of motif a1 relates to the rhythm in bars 1/2, 9/10 and 17 f. as well as to the upward five-tone row in measure 9 of children's piece 1.

| Measures 1 to 4, a1 |

While a1 ends in the major dominant, the almost literal repetition in a2 finds its way back to the minor tonic.

The motif b1 is characterized by the constant eighth note movement and a motif core made up of two tone steps followed by a third in the opposite direction. Melodic or rhythmic references exist e.g. B. to the beginning of the third children's play or to eighth runs in the first children's play.

| Bars 8 to 12, b1 |

The motif, which is particularly suitable for spinning and changing, undergoes various changes in the further course. In Part III, further voices are added to a or parts of the motif are made independent, varied and led to a conclusion that acts as a sequel.

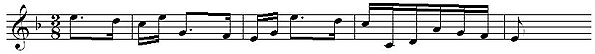

The sixth children's play

The sixth children's piece has a special position in op. 72 - because of the very fast pace, because of the volume, the pianistic demands and also because of the differentiated form that cannot be presented in detail here. The starting motif is in 3/8 time.

| Measures 1 to 6 |

The triad-oriented structure of the initial motif from the first children's piece can be found in the downward triads. The listener encounters the melody tones of bar 1 of the first children's piece (without a prelude) in the step-wise upward leading tones of the triad figures and in the jump to the tonic keynote. The melody, which is led downwards in steps, corresponds to the melody in bars 1 and 2 of the first children's piece. In bar 17, a figure appears for the first time that has a rhythmic relationship to the downward triads of the beginning.

| Bars 14 to 18 |

In fact, it also sounds with triad notes in the further course. The decisive factor, however, is that this figure is divided into two parts, which in the further course leads to an extraordinary animation. From bar 67 this "two-parter" is also offset, ie it exceeds the bar limit. In the piece, comprehensibility is ensured primarily through the sophisticated motivic references. Mendelssohn's way of composing, called “interweaving”, leads to a very variable development of forms.

Features of the composition for children

Mendelssohn's children's pieces show that he also retained his compositional principles in music for children. When he wrote for children, he didn't start over with composing. Perhaps his style is particularly clear and condensed in the children's pieces. The pianistic demands of the pieces are especially adapted to children. Nevertheless, obviously those children are meant who have already made progress on the instrument. Using the example of a comparison of the fourth and sixth children's pieces (follow-up accompaniment or agitato piece) with songs without words belonging to the same type, it can be made clear: Compared to songs without words, the children's pieces tend to have fewer accidentals and are only in frequently used ones Time signatures and tend to be shorter.

| follow-up accompaniment | sign | Time signature | Bars |

| Children's play, Op. 72 No. 4 | 2 (D major) | 6/8 time | 44 bars |

| Song without words, op.38, no.2 | 3 (C minor) | 2/4 | 28 |

| Song without words, Op. 53, No. 6 | 3 (A major) | 6/8 | 126 |

| Song without words, Op. 67, No. 3 | 2 (B flat major) | 2/4 | 49 |

| Agitato piece | sign | Time signature | Bars |

| Children's play, Op. 72 No. 6 | 1 (F major) | 3/8 | 97 |

| Song without words op.19b no.5 | 3 (F sharp minor) | 6/4 | 119 |

| Song without Words, Op. 30, No. 4 | 2 (B minor) | 3/8 | 178 |

| Song without words, op.38, no.5 | - (A minor) | 12/8 | 54 |

In all children's pieces the span of an octave is assumed for the right and left hand (e.g. No. 1 bars 4 and 8, No. 2 bars 2 and 34, No. 3 bars 8 and 12, No. 4 bars 3, No. 5 bars 2 and 3, No. 6 bars 5 and 11). This also makes it clear that the pieces are not intended for small children. However, intervals that go beyond the octave are deliberately excluded, as they occur in some songs without words (e.g. op. 19b No. 4 bar 2 - right a 'and h ″, 19b No. 1 bar 6 - left D and f, op. 30 no.1 bar 2 - right h ′ and g, op.38 no.2 bar 12 - left E and g). Some adult pianists will also play a “compromise legato” at these points. This way of playing, to be learned in class, could also be used for small hands for octaves in children's pieces. In contrast to the children's pieces, the songs without words contain more extensive and technically more demanding passages or require e.g. B. the independent management of different voices in one hand. A comparison of the “initial pieces” from the children's pieces (op. 72 no. 2) and from booklet 6 of the songs without a word (op. 67 no. 1) shows, for example. B .: In the song without words, the alternation of the accompanying figures between the hands (bars 1 and 5), the simultaneous playing of melody and accompaniment in one hand (bar 5) and the ostinate h ′ (bar 29) also appear in other places Accompanying figures and melody stand out as technical and musical requirements.

Reception of the children's pieces

Music written for children is often given less attention in the overall work of a composer. In the case of Mendelssohn, there is also the fact that he wrote only a few pieces for children. It is known from letters that the composer also wrote children's symphonies in addition to the “Two Other Children's Pieces” and the “Bear Dance”. These pieces were performed in the family at Christmas in 1827, 1828, and probably 1829. The locations of the autographs are not known or the autographs are lost. The small number of pieces expressly intended for children and the special charisma of Schumann's albums for young people are probably the main reasons why Mendelssohn's children's pieces often receive little or no attention. This concerns z. B. Hans Christoph Worbs: Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1974), Karl-Heinz Köhler: Mendelssohn (1995) or Arnd Richter: Mendelssohn Life, Works, Documents (2000). In some cases, comparisons are made with Schumann. If Schumann's differently designed music for children is taken as a model for children's music at all, the comparison can be unfavorable:

“Certain compositions by Mendelssohn, even if they are characteristic, have been saved from oblivion by the name of the creator. One should pay more attention to the last work Mendelssohn himself published, the “Kinderstücke” Werk 72, than is usually the case. It is true that these are not Schumann's “children's scenes” and none of the other Schumann's pieces for children and adults, and the wonderful poetry and gripping power of these are not present here. But taking into account Mendelssohn's dampening spirit, these things also retain their value. "

If it is noted that Mendelssohn has found his own way of composing for children - against the background of an extraordinarily extensive life's work in terms of music education - the children's pieces can also appear in a different light.

literature

- Carl Dahlhaus: Songs without words (= ders .: Collected writings in 10 volumes. Ed. By Hermann Danuser, Volume 5: 19th century II). Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2003, pp. 518-522.

- Eduard Devrient: My memories of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy and his letters to me. Weber publishing house, Leipzig 1891.

- Sebastian Hensel: The Mendelssohn family 1729 to 1847. According to letters and diaries. Behr-Verlag, Berlin 1908.

- Donald Mintz: Mendelssohn as Performer and Teacher. In: Douglass Seaton (ed.): The Mendelssohn Companion. Greenwood Press, London 2001, pp. 87-142.

Web links

- Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Six Children's Pieces, op. 72 : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Six children's pieces for the pianoforte op. 72. In: Ulrich Scheideler, Christa Jost (eds.): Mendelssohn piano works, Urtext. Volume II. G. Henle, Berlin 2009, pp. 192 to 202.

- ↑ cf. R. Larry Todd: Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. His life His music. Carus, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-89948-098-6 , p. 481.

- ^ A b o. V .: Mendelssohn in England: A centenary tribute. In: The Musical Times. February 1, 1909, pp. 87 f. ( JSTOR 906967 ).

- ↑ cf. Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Two more children's pieces. In: Ulrich Scheideler, Christa Jost (ed.): Mendelssohn piano works. Urtext, Volume II. G. Henle, Berlin 2009, pp. 203 and 204.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Emil or about education. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 1971, p. 69.

- ↑ cf. Wilfried Gruhn: History of Music Education. 2nd Edition. Wolke, Hofheim 2003, ISBN 3-936000-11-5 , p. 25.

-

↑ These include:

Johann Joachim Quantz: Attempting an instruction to play the flute traversière. Reprint of the edition Berlin 1752. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Bärenreiter-Verlag, Munich Kassel 1992.

Friedrich Reichardt: About the application of music in early education. In: Johann Friedrich Reichardt: Letters concerning the music. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, p. 164 f.

Johann Friedrich Reichardt: To the youth. In: Johann Friedrich Reichardt: Letters concerning the music. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, p. 165 ff.

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Attempt on the true way of playing the piano. First and second part. Facsimile reprint of the 1st edition, Berlin 1753 and 1762. VEB Breitkopf & Härtel Musikverlag, Leipzig 1969.

Johann Adam Hiller: Instructions for musically correct singing with sufficient examples. Johann Friedrich Junius, Leipzig 1774.

Johann Adam Hiller: Instructions for musical, delicate singing. Photomechanical reprint of the original Leipzig 1780 edition. Edition Peters, Leipzig 1976.

Leopold Mozart: Thorough violin school. Facsimile reprint of the 3rd edition, Augsburg 1789. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1968. - ↑ cf. Isabel Eicker: Children's pieces. Albums in 19th century piano literature addressed to children and composed on the theme of childhood. Bosse, Kassel 1995, ISBN 3-7649-2623-6 , p. 14.

- ↑ cf. Irmgard Heimlich: German-language piano textbooks from 1750 - 1850 in their social contexts. Investigation of the content design and reflection of music-cultural processes. Dissertation A, Humboldt University Berlin, 1990, pp. 3–9, 206 ff., 90.

- ↑ cf. Hermann Erler: Robert Schumann's life. Described from his letters. Volume II. Ries & Erler, Berlin 1887, p. 61 f.

-

↑ cf. Isabel Eicker: Children's pieces. Albums in 19th century piano literature addressed to children and composed on the theme of childhood. Bosse, Kassel 1995, ISBN 3-7649-2623-6 , p. 248

. also Matthias Schmidt: Composed Childhood (= spectrum of music. Volume 7). Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2004, ISBN 3-89007-585-1 , p. 52. - ↑ Book 1 (1832, op. 19), Book 2 (1835, op. 30), Book 3 (1837, op. 38), Book 4 (1841, op. 53), Book 5 (1844, op. 62) , Book 6 (1845, op.67)

- ↑ cf. Christa Jost: Mendelssohn's songs without words (= Frankfurt contributions to musicology. Volume 14). Hans Schneider, Tutzing 1988, ISBN 3-7952-0515-8 , pp. 72-186.

- ↑ cf. Christa Jost: Mendelssohn's songs without words (= Frankfurt contributions to musicology. Volume 14). Hans Schneider, Tutzing 1988, ISBN 3-7952-0515-8 , p. 72 ff. (E.g. op.19b, 4, op.30,3, op.38,4)

- ↑ cf. Christa Jost: Mendelssohn's songs without words (= Frankfurt contributions to musicology. Volume 14). Hans Schneider, Tutzing 1988, ISBN 3-7952-0515-8 , p. 182 ff. (E.g. op.19b, 1, op.30,1, op.38,1)

- ↑ cf. Christa Jost: Mendelssohn's songs without words (= Frankfurt contributions to musicology. Volume 14). Hans Schneider, Tutzing 1988, ISBN 3-7952-0515-8 , pp. 139 ff. (E.g. op.38.2, op.38.5, op.53.6)

- ↑ cf. Christa Jost: Mendelssohn's songs without words (= Frankfurt contributions to musicology. Volume 14). Hans Schneider, Tutzing 1988, ISBN 3-7952-0515-8 , p. 100 ff. (E.g. op. 30,2)

- ↑ cf. Bernhard R. Appel: Robert Schumann's "Album for the Young", introduction and commentary. Atlantis Musikbuch-Verlag, Zurich and Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-254-00237-7 (new edition: Schott, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-7957-8746-2 ), p. 85 ff.

- ↑ cf. Christa Jost: Mendelssohn's songs without words (= Frankfurt contributions to musicology. Volume 14). Hans Schneider, Tutzing 1988, ISBN 3-7952-0515-8 , p. 68 ff.

- ↑ cf. Isabel Eicker: Children's pieces. Albums in 19th century piano literature addressed to children and composed on the theme of childhood. Bosse, Kassel 1995, p. 177.

-

↑ cf. Friedhelm Krummacher: On Mendelssohn's type of composition. Theses using the example of string quartets. In: Carl Dahlhaus (ed.): The Mendelssohn problem (= studies on the history of music in the 19th century. Volume 14). Bosse, Regensburg 1974, pp. 174 and 182.

cf. Friedhelm Krummacher: Mendelssohn - the composer. Studies in chamber music for strings. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 1978, p. 136 ff. - ↑ cf. Friedhelm Krummacher: On Mendelssohn's type of composition. Theses using the example of string quartets. In: Carl Dahlhaus (ed.): The Mendelssohn problem (= studies on the history of music in the 19th century. Volume 14). Bosse, Regensburg 1974, p. 177 ff.

- ↑ The following sound files were created automatically via the MIDI export of a notation program.

-

↑ cf. Friedhelm Krummacher: On Mendelssohn's type of composition. Theses using the example of string quartets. In: Carl Dahlhaus (ed.): The Mendelssohn problem (= studies on the history of music in the 19th century. Volume 14). Bosse, Regensburg 1974, pp. 174 and 182.

cf. Friedhelm Krummacher: Mendelssohn - the composer. Studies in chamber music for strings. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 1978, p. 136 ff. - ↑ cf. Christa Jost: Mendelssohn's songs without words (= Frankfurt contributions to musicology. Volume 14). Hans Schneider, Tutzing 1988, ISBN 3-7952-0515-8 , pp. 139 ff. And p. 100 ff. The songs without words used for comparison are sometimes viewed by Jost as particularly characteristic of the respective type (prototype).

- ↑ cf. Ralf Wehner: Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Thematic-systematic directory of musical works (MWV) (= Leipzig edition of the works of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Series XIII, catalog of works Volume 1A). Study edition. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 2009, pp. 242–245 (P 4, P 6, P 8).

-

↑ Hans Christoph Worbs: Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy ( Rowohlt's monographs ). Rowohlt, Hamburg 1974.

Karl-Heinz Köhler: Mendelssohn ( The great composers ). JB Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar 1995.

Arnd Richter: Mendelssohn life works documents. Atlantis Musikbuch-Verlag, Zurich and Mainz 2000. - ^ Bernhard Bartels: Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Man and work. Walter Dorn Verlag, Bremen and Hanover 1947, p. 236.

- ↑ cf. z. B. Leipzig University of Music