Swill milk scandal

Swill milk scandal (German about pig feed milk scandal ) describes a food scandal in the US state of New York in the 1850s. The New York Times suggested in 1858 that approximately 8,000 infants had died as a result in 1857.

Name and background

The name comes from feeding cows with pig feed, more precisely with fermentation residues ( vinasse ) of distilleries in the city. The milk was also adulterated with plaster of paris, starch and molasses , and the cows themselves were kept under completely unacceptable hygienic and animal husbandry conditions. The additives made the milk keep a little longer and made it appear sweet-tasting longer.

At that time, milk from the rural environment was also massively adulterated and added with additives. In 1853 around 90,000 quarts of cow's milk were imported into the city, but just under 120,000 quarts of land milk (1 US liq.qt. corresponds to 0.9464 liters) were sold to end customers.

The pasteurization process, invented in 1876, was not systematically applied to milk until the turn of the century (by Franz von Soxhlet ). The connections were only recognized precisely in the course of the 20th century.

consequences

Of almost 15,000 deaths in New York in 1857, more than half were children under the age of 5, which was considered an exceptionally high child mortality rate at that time . The New York Times assigned 8,000 dead children to swill milk .

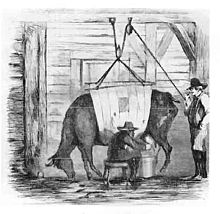

New York was then a city overpopulated by poor immigrants, with cholera outbreaks in 1854 and yellow fever outbreaks in 1856 , each with several hundred deaths. Adequate cooling technology did not come into large-scale use until 20 years later. The connection was uncovered in a sensation-seeking manner by Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper , among others . Leslie especially fought with the Irish-born transport workers and major distillers such as Bradish Johnson . The cattle stalls and dairies close to the city , which were built next to the schnapps distilleries, were notorious for miles of unpleasant smells and unbearable hygienic conditions. The still hot fodder from the mash waste from the distillers contained not only some nutrients but also a certain alcohol content, which the cows quickly got used to and dulled. The animals lay in their own droppings and were milked, despite udder diseases and rashes, without meeting a minimum of hygienic standards.

Despite the exposure and the public demand to restrict the practice, local politicians, in particular the Democratic Alderman Michael Tuomey (aka "Butcher Mike"), tried to prevent any further investigation, which initially succeeded. Leslie's anti-Irish reservations also played a role. Butcher Mike had grown up within Tammany Hall , a political clan of the Democratic Party . Among other things, reference was made to chemical studies that confirmed the products sold under fancy names such as Orange County Milk to have a higher nutrient content than natural milk.

Due to the public outcry that followed and the involvement of external authorities, the first regulatory measures were taken in 1862. Improvements in quality as a result were due to increasingly better competition from the rural area. The official control capacities had rather decreased in the wake of the civil war .

A nationwide stricter legislation came about in 1905 through the Pure Food and Drug Act and was founded in particular by Upton Sinclair's socially critical novel The jungle about the meat industry in Chicago, also against massive opposition from the Democrats who dominated there.

reception

In the USA, parallels were drawn with the Chinese milk scandal in 2008 , in both cases there was great economic growth and a government that was either unable or unwilling to regulate. In both cases, it was a functioning public that ultimately pushed through the education and improvements in food control.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Swill - Milk and Infant Mortality , in: The New York Times , May 22, 1858

- ↑ a b John Mullaly: The Milk Trade in New York and Vicinity: Giving an account of the Sale of Pure and adults Rated Milk . Fowlers and Wells, 1853, pp. 39 ( digitized in Google book search).

- ↑ a b c d David B. Sachsman, David W. Bulla: Sensationalism: Murder, Mayhem, Mudslinging, Scandals, and Disasters in 19th-Century Reporting . Transaction Publishers, 2013, ISBN 978-1-4128-5171-8 , pp. 132 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Andy Hwang, Huang Lihan: Ready-to-Eat Foods: Microbial Concerns and Control Measures . CRC Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4200-6862-7 , pp. 88 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Bee Wilson : The Swill is Gone. In: The New York Times. September 29, 2008, accessed September 30, 2008 .

- ↑ GS Wilson: The Pasteurization of Milk. In: British medical journal. Volume 1, Number 4286, February 1943, ISSN 0007-1447 , pp. 261-262, PMID 20784713 , PMC 2282302 (free full text).

- ↑ a b The Swill-Milk Nuisance , in: The New York Times , June 8, 1858

- ↑ Bee Wilson: Swindled . Princeton University Press, 2008, pp. 162 .

- ↑ Bee Wilson: The Swill is Gone. In: The New York Times. September 29, 2008, accessed September 30, 2008 .