Time competition

Time competition (also time management, not to be confused with personal time management , English time based competition or time based management) is a business concept in the field of strategic controlling in which time is placed in the foreground instead of costs and quality as the primary target variable . In the time competition, the position of a time-oriented company relative to other competitors is examined. The aim of the time management approach is to increase the effectiveness and efficiency with regard to time, while focusing on the own company, in order to achieve strategic competitive advantages over competitors.

history

The time competition can be seen as a further development of the competition strategies previously developed - price, cost and quality competition . With these, a competitive advantage should be achieved through lower prices, lower costs or higher quality compared to competing products / services. After these strategies were exhausted in some industries, the importance of time as a competitive factor was recognized.

As early as the 1920s, the American automobile manufacturer Henry Ford viewed time as a strategic resource that, like materials, should be used economically, i.e. not wastefully. He established a just-in-time production system , which led to an enormous reduction in production times while at the same time limiting flexibility. A consistent and holistic further development of this system can be found in the Toyota production system, which was developed in the Toyota Motor Corporation from the 1950s and which set itself the goal of eliminating waste of resources and expressly including the time factor. The elimination of waste for the benefit of improving added value has been extended to the entire company processes such as production, but also management, research & development and order processing. With Toyota's economic success, its time-oriented competitive strategy also found increasing acceptance in other Japanese companies. In contrast, the importance of this strategic approach in the western world was only recognized in the late 1980s and early 1990s and was developed and recommended by various consulting companies.

Time as a competitive factor

In many industries, companies have been facing the following economic challenges since the late 1980s:

- dynamically changing and steadily tightening competitive conditions in partially saturated markets,

- the fragmentation of the mass markets into small niches, mainly caused by the increasing individualization of demand and, as a result, a wider variety of products to be offered with sales volumes that are difficult to predict,

- the shortening of the product life cycle and the increasing difficulty of forecasting future customer requirements and sales volumes.

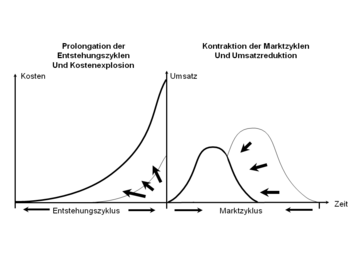

This means that customer-oriented companies are faced with the task of developing a broader range of products and of renewing them at ever shorter intervals, which shortens the time a product remains on the market and thus worsens the possibility of amortizing the development expenses already made. In the literature, two effects are described that illustrate the importance of time in today's economy. These are the time trap and the time scissors.

Time trap

The time trap is used when, due to shortened market cycles, exploding development costs and increasing complexity and duration of development processes, the research and development costs exceed the profits that are realized during the marketing phase.

Time scissors

Companies are forced to constantly adapt to their environment in order to remain competitive. In the context of increasing market dynamics , this means a reduction in the available response time. In contrast, however, there is an increase in the required response time in connection with increasing complexity. The difference between the required reaction time with increasing complexity and the available reaction time with increasing dynamics is called the time gap.

Time management

Time management tasks

Become one of the tasks of time management

- the economic design of time periods, i.e. optimization from a time perspective, also called speed management, and

- the economical design of times, also called optimal timing,

counted.

The task of speed management is to sustainably accelerate operational processes and generally to acquire the ability to do this repeatedly. However, this is not an end in itself (general time minimization), but with a view to the company's success (time optimization). The essential task of optimal timing is to determine the optimal time to enter and exit the market. If a product is introduced too early or too late in relation to the set goals, this can have significant consequences, see the section on the time trap. Here the concept of the “strategic window” is of great importance. It is assumed that there is only a certain period of time in which the marketing of the product is promising because market requirements and company capabilities match well. The aim of optimal timing is therefore to set the time of market entry as close as possible to the time at which the “strategic window” opens.

Time management principles

Time orientation

The value chain is organized in a time-oriented manner, time targets are collected and used as the basis for aligning competitive strategies.

Quantum leap orientation

With the objective of accelerating operational processes and for the purpose of securing competitive advantages, small changes are not primarily sought, but quantum leap-like shortening of response times.

Process orientation

Similar to the concepts of lean manufacturing (lean production) and the lean management (lean management), the focus is on continuous processes as opposed to structured functional organizational units. In this way, process-inhibiting interfaces are recognized and smoothed out for the benefit of accelerating operational processes. The aim is to eliminate time spent on non-value-adding activities in the sense of wasting time as a resource by setting up a continuous production process.

Value orientation

In interaction with process orientation, operational processes should be designed in such a way that the proportion of value-adding activities is maximized.

Team orientation

Personnel are process-oriented, temporarily or permanently, grouped together in teams in order to avoid function-related interfaces and thus the potential for wasting time. Teams are measured by their overall success.

Response times as a target of time management and time competition

In general, the response time is the time span between an impulse to the company and the company's reaction to it. Compared to other economic time models, such as the product life cycle , time management naturally distinguishes between entrepreneurial processes and production phases in much more detail:

- system-internal response times, such as

-

Manufacturing lead time, which is divided into

- direct processing time ( standard time ), d. H. the time devoted to value-adding activities

- indirect processing time (time for changes and reworking, coordination time, set-up time , transport time), d. H. process driving activities without monetary increase in benefit,

- Lay time , d. H. process inhibiting activities;

-

Manufacturing lead time, which is divided into

- externally relevant response times, such as

- Replacement time for parts and components (time-to-production),

- Delivery time (delivery service) (time-to-customer), time between receipt of order and order fulfillment,

- Service time, time between service order and execution,

- (Market-into-time) introduction time, consisting of the development time (time to market-) and the market introduction and market penetration time;

- Behavioral response times, like

- Decision time,

- Learning time.

In addition to this classification, the introduction time is assigned to the innovative activity cycle and the replacement, production, delivery and service time to the operational activity cycle. The two activity cycles are based on the systemic product life cycle , a further development of the integrated product life cycle , with the former essentially corresponding to the creation cycle and the latter to the production, market and aftercare cycles.

A shortening of the response times contributes significantly to the fulfillment of the tasks of the time management, the acceleration of operational processes and thus also the possibility to choose operational decision times more freely, with the benefit of an optimal timing.

Time-based competitive strategies

In accordance with the tasks of time management, time-based competitive strategies aim at time spans of operational processes and the optimal choice of times. In general, time-based competition strategies are promising if there is a market in which the customer, corresponding to the time competitor, places a strong focus on time aspects, customers, their needs, for example

- Time saving,

- Punctuality,

- Topicality and novelty and

- Time flexibility

are described. In order to satisfy time-based customer needs, a company can rely on a time-based differentiation strategy in order to strive for price leadership through a noticeable increase in the benefit of time-oriented customers . Conversely, time-based strategies can be used in cost leadership strategies because of the elimination of time wasted in the production process and the associated cost reduction . Time competition strategies naturally lead to a combination of the two classic strategies and can therefore be viewed as a time-based outpacing strategy. Since several competitive factors such as costs, quality and time are recorded by time-based strategies, they are expected to have a particularly lasting effect. Regarding the choice of an optimal time to enter the market, the following options are available, see also time-oriented competitive strategies :

- Pioneer (company that is the first to launch the new product on the market and is initially unrivaled),

- Early follower (will be active in the market soon after the pioneer),

- Later follower (enters the market with a significant delay).

In general, all strategies have their advantages and disadvantages, which makes it all the more important to be able to choose your own strategy through short response times, instead of being pushed into the next role by innovative competitors.

With regard to the market battle with competing time competitors, a distinction is made between direct and indirect strategies. Direct strategies aim at an open discussion about a massive increase in product diversity, a significant shortening of the product life cycle and the necessary shortening of development time. Direct strategies require a high level of resources and involve a high level of risk. In the case of indirect strategies, a distinction is made between the systematic strategy of delay and the strategy of deception. With the systematic delay strategy, the time reductions are made step by step so as not to arouse the attention of competitors and to prevent possible countermeasures. If, after some time, the competitor realizes the full extent of the competitor's time advantage, the market can even exit. In the case of the deception strategy, misleading information is made available to competitors in which, for example, false reasons for the improvements achieved are published in the media.

Time cost accounting

A time cost accounting was developed for the quantitative support of management decisions and for the planning, management and control of time-relevant processes . Your task is to determine the proportion of time-driven costs in the total costs and to break them down according to time cost types. In terms of time-relevant costs, a further distinction is made between those with a clear time driver and those without a clear time driver. In particular, the time cost calculation also includes values that are not classically counted as costs. These are also known as opportunity costs . In time cost accounting, this includes lost revenue due to time problems such as exceeding delivery times.

Conceptually, the expected value and variance of certain response times, mostly the lead time, are examined. Considering the variance, a distinction is made between time compliance costs for a given delivery time, i.e. H. Costs incurred as a result of increased efforts to meet delivery times and time deviation costs, d. H. Opportunity costs or contractual penalties for non-compliance with delivery dates. With regard to the expected value of the lead time, a balance is drawn between the costs of accelerating value creation processes and the cost savings potential through the acceleration. In terms of time optimization taking into account, there is no acceleration at any price, but taking into account the respective costs.

Individual evidence

- ↑ H.-G. Baum, AG Coenenberg , T. Günther: Strategic Controlling. 4th edition. Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 2007, p. 138.

- ↑ K. Bleicher: On the temporal in corporate cultures. In: The company. Vol. 40, No. 4, 1986, pp. 259-288.

- ↑ V. Kirschbaum: Business success through time competition: strategy, implementation and success factors . Dissertation. Munich 1995, p. 54.

- ^ DF Abell: Strategic Windows. In: Journal of Marketing. Volume 42, No. 7, 1978, pp. 21-26.

- ↑ G. Stalk, TM Hout: Time competition. 3rd, revised edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York, 1992, p. 76f.

- ↑ H.-G. Baum, AG Coenenberg, Th. Günther: Strategic Controlling. 4th edition. Schäffer Poeschel, 2007, p. 171.

- ^ Th. Günther, J. Fischer: Time costs. In: Th. M. Fischer (Ed.): Cost Controlling - New Methods and Contents. Schäffer-Poeschel, 1999, p. 602.

literature

- DF Abell: Strategic Windows. In: Journal of Marketing. Volume 42, No. 7, 1978, pp. 21-26.

- H.-G. Baum, AG Coenenberg, Th. Günther: Strategic Controlling. 4th edition. Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-7910-2545-2 .

- K. Bleicher: On the temporal in corporate cultures. In: The company. Volume 40, No. 4, 1986, pp. 259-288.

- H. Drüke: Competence in the time competition. Policies and strategies in the development of new products. Springer, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-540-62458-9 .

- J. Fischer: Time competition: Basics, strategic direction and economic evaluation of time-based competition strategies. Verlag Franz Vahlen, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-8006-2667-5 .

- Th. Günther, J. Fischer: Time costs. In: Th. M. Fischer (Ed.): Cost Controlling - New Methods and Contents. Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-7910-1407-2 , pp. 591-624.

- V. Kirschbaum: Company success through time competition: strategy, implementation and success factors. Hampp, Munich / Mering 1995, ISBN 3-87988-137-5 .

- G. Stalk, TM Hout: Time Contest. 3rd, revised edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 1992, ISBN 3-593-34409-2 .