Bitter from Bitterfeld

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| Original title | Bitter from Bitterfeld. An inventory |

| Country of production | Federal Republic of Germany |

| original language | German |

| Publishing year | 1988 |

| length | 30 minutes |

| Rod | |

| Director | Rainer Hällfritzsch, Margit Miosga, Ulrich Neumann |

| production | Workshop for intercultural media work e. V. (WIM) |

| camera | Rainer Hällfritzsch |

| cut | Rainer Hällfritzsch, Margit Miosga, Ulrich Neumann |

Bitter from Bitterfeld. An inventory , generally short bitter from Bitterfeld , is illegal in the GDR turned documentary from the year 1988 . It showed the extent of environmental pollution in the industrial region around Bitterfeld, which is characterized by chemical plants . This attempt to create a counter- public was a joint undertaking by East Berlin oppositionists from the Arche green-ecological network , local environmentalists and West Berlin filmmakers.

The video film was initially shown in private and church circles in the GDR. The ARD magazine Kontraste broadcast excerpts for the first time in autumn 1988; they have been adopted by many television stations abroad. The show was the talk of the day in Bitterfeld. In the GDR she made the Ark known. The GDR State Security did not succeed in convicting those involved in the production of the film. After the fall of the Berlin Wall , reporting by German and foreign journalists on the situation in the “ chemical triangle ” was based on these film clips.

content

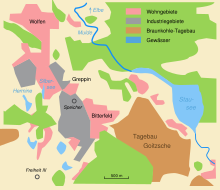

Entrance pictures show the landscape devastated by the lignite opencast mine , high factory chimneys with exhaust plumes in different colors, a granary in front of a plant for chlorine production as well as urban residential streets with gray facades and crumbling buildings. From the off , a spokeswoman explains that around 2000 products for household and garden, industry and agriculture are manufactured in Bitterfeld, including detergents and plastics , paints and fertilizers , weed and pesticides . The chemical industry gets rid of its waste by dumping it in the extensive pits of the opencast mines, by discharging it into the Elbe tributary Mulde and by releasing it into the air. The spokeswoman comments: “Bitterfeld is falling apart. Bitterfeld is soot-black. Bitterfeld stinks. Bitterfeld is now considered the dirtiest city in Europe. "

The old, barely modernized factories run with "three times the capacity utilization". Only ten percent of the large chimneys are registered as emitters and are controlled by the state. The costly decision to trigger the only smog alarm system in the GDR rests with the General Director of the Bitterfeld Chemical Combine . Liquid waste flows as diluted, colored waste water directly into the biologically dead hollow. Vapors, bubbles, and odors indicate chemical reactions. The only purification method is the addition of limestone . Samples showed values for nitrates and nitrites that were five to ten times higher .

The brown coal seams are up to 90 meters deep. Amber is often found here, which is sold to the west with the indication of origin from the Baltic Sea . Since the level of the groundwater is 22 meters under natural conditions, the water is pumped into the basin. Neighboring areas dry out, the plants die. Charred opencast mines served and still serve as unsupervised, uncontrolled and undocumented waste dumps. According to the spokeswoman, warfare agents from weapons production during the Second World War , halogenated and chlorinated hydrocarbons , including residues from the production of DDT and other substances , are stored under embrittled cover layers . Under landfill conditions, sealed and with heat development over 170 degrees, the " Seveso- Poison" dioxin can arise. Camera pans show tipped barrels and canisters with warning labels in the Freedom III pit . Substances run out of the transport containers. The soil is wet with chemicals.

Phenyl chloride disease , fluorosis and graphite diseases occur more frequently among employees . They show up in the degenerating bones of the fingertips and “outgrowths the size of a tomato on the wrists.” Some employees have to wash for up to an hour a day. The earnings of the employees contain up to seven percent risk allowances. The shift workers among the total of 23,000 employees in the combine get 38 days of annual leave. Five to eight times more people than the national average develop bronchitis and pseudocroup . Life expectancy is several years below average.

The serious chemical accident of 1968 is well known, but nothing of "minor accidents" has been made public. A pipeline that allegedly only transports ashes from lignite combustion that have been extinguished in water bursts in cold winters. The broth then flows uncontrollably into the area. The film shows residues from the paper, plastic and other chemical industries at the outflow of the pipeline. At the edge of a wide wasteland with shimmering sludge , to which the pipeline leads, are new residential buildings. The Hermann Falke hiking trail runs through the desert. A sign can be seen announcing danger to life if the path is left.

The Silbersee , which is surrounded by dead trees and also a former opencast mine, has been taking in all the wastewater from the Orwo film factory for 70 years through open supply lines . They are diluted in the lake before they drain through the trough. The water contains heavy metals and is very acidic , "our analyzes" confirm.

Bitterfeld offers "the image of a dirty and barren provincial town," says the spokeswoman. The city once belonged to the "red heart of Central Germany" and was a center of the workers' protest on June 17, 1953 , "which was only ended by Russian tanks at the gates of the chemical combine". Now, however, it is intimidated whoever names the environmental problems by name. The film ends with a quote from the novel Flugasche by the writer Monika Maron : “The people in Bitterfeld have settled down and got used to being residents of Bitterfeld and being sprinkled with dirt. Perhaps it is nothing but crude and heartless to tell them: You have been forgotten, sacrificed for more important things. And I can't change it. "

Between the sections of the film, images of emergency money from the city of Bitterfeld from 1921 with motifs from lignite mining and processing are faded in. The text is spoken by two female voices. The pictures are accompanied by jazz music. The opening and closing credits of the film were handwritten. The credits show the person in charge “The green network i. of the Protestant Church Arche and Ätz-Film-KGB ”.

Emergence

Idea and project

In the spring of 1988, the opposition movement split in the GDR capital (East) Berlin. In addition to the environmental library , the Arche green-ecological network was created . Its activists counted on a nationwide coordination of working-sharing environmental groups and thus were seen by the employees of the environmental library as centralistic and too little democratic. In order to establish contacts, Arche members such as Carlo Jordan and Ulrich Neumann have been visiting the industrial region of Halle since the beginning of 1988 .

Neumann got to know Hans Zimmermann in Bitterfeld , a skilled chemical worker and head of a construction crew whose child was sick with pseudo croup. For years Zimmermann has been researching the improper handling of production residues from the chemical combine, the health impact of the residents and the damage to nature. He also wrote petitions to the district council . Now he showed the Berliners around the region.

In spring 1988, the West Berlin SFB radio journalist Margit Miosga, who was friends with Neumann, took part in a visit to Bitterfeld. On the trip they discussed the possibilities of an Arche film about Bitterfeld. In May the project was decided in a small group.

technology

In the GDR, amateurs used the widely popular Super 8 cine film format to record moving pictures in their private lives. Synchronous sound-image recordings and non-industrial copying of films were hardly technically possible. The medium was therefore hardly considered for political-documentary work.

Video technology was still not widely used. For private or church use, players could officially “only at utopian prices” for marks , in Intershops for DM or through Western contacts. Some smuggled cameras ended up in the hands of employees of critical groups. But the few video editing stations were hardly accessible, even for approved productions by independent filmmakers. The Ark activists had no access to a camera or a production studio.

Because no counter -public could be created without editing and copying options, Miosga turned to the West Berlin documentary filmmaker Rainer Hällfritzsch, who she knew. He had just co-founded the independent workshop for intercultural media work (WIM eV) in Berlin-Schöneberg , had the necessary technology with a VHS camcorder and the studio and was ready to take part in the conspiratorial project.

Film team and shooting

The shooting day was Sunday, June 25, 1988. On this day the final of the European Football Championship 1988 between the Netherlands and the Soviet Union took place in Munich . The game started at 3:30 pm; ZDF broadcast with pre- and post-coverage from 2:45 p.m. to 6:10 p.m. The GDR television also showed the final. The GDR team was not qualified and the FRG team was eliminated in the semi-finals on June 21st. Nevertheless, the film team expected that only a few people would be around. “Hopefully the Stasi will also be sitting in front of the television,” the environmental activists calculated. The Evangelical Church Congress in Halle also tied Stasi and police forces in the region.

The driver was the East Berlin doctor Edgar Wallisch, who had applied for an exit visa and had just been banned from working at the Charité . He owned a Lada "like the one that the Stasi drove". The car was dark blue and had a Berlin license plate. It was often used for ark activities. He was supposed to go to Halle for Environment Day that weekend and was directed to Leipzig at short notice on Saturday .

Miosga and Hällfritzsch also traveled to the GDR the day before the shooting. With a rental car to make it difficult to trace the number plate, Miosga took the border crossing point Invalidenstrasse . Hällfritzsch entered via the Friedrichstrasse S-Bahn station . His video camera, hidden in a shoulder bag, went unnoticed. The import would have been legal, but could have left a trace for the GDR authorities if customs had registered it. The two empty cassettes intended for the recordings were confiscated from Hällfritzsch's travel bag. Miosga picked Hällfritzsch up at the train station and bought two new ones in the nearby Intershop.

In the evening, most of the participants met in a restaurant in Leipzig. Wallisch only found out now that an illegal film project was planned. He, Neumann, Miosga and Hällfritzsch stayed with the exhibition organizer Peter Lang to avoid registering in a hotel. Alcohol consumption delayed the group's departure by an hour on the day of shooting.

In order to distract the Stasi, Neumann drove to the Kirchentag in Halle in the morning and distributed the first copies of Arche Nova No. 1 there. Wallisch took the two West Berliners to Zimmermann in Bitterfeld and the three to the locations chosen by Zimmermann. They began shooting with the Goitzsche's large open-cast mine , drove up the Muldensteiner Berg with its view of the granary in Greppin and the Mulde weir in Jeßnitz . At around 2 p.m. they reached the Silbersee, the remaining hole in the St. Johannes opencast mine. Wallisch took water samples there; the video shows his arms and hands filling a plastic bottle. Then they changed the vehicle. Zimmermann, Miosga and Hällfritzsch let the activist Jörg Klöpzig drive them. From his Lada, which had a less conspicuous local license plate, they filmed the deserted Bitterfeld during the football game. In the evening the shooting followed at the dump Freedom III .

Then Wallisch brought Miosga and Hällfritzsch back to Leipzig. With the rental car that was left there, they drove to a suburb of Leipzig where Hällfritzsch's mother had lived. There they took safe recordings on the second cassette so that Hällfritzsch could have justified carrying the camera at the border. The cassette with the raw material from Bitterfeld initially stayed in the east.

The next day, Miosga and Hällfritzsch left separately. Border officials held Hällfritzsch in an adjoining room for an hour - as it turns out in the end, only because of a mistake during the visa control. The camera was not discovered again. The doctor Wallisch found out later through a professional call to Zimmermann that he was fine. The “outstanding example of the possibilities offered by cross-border cooperation between opposition activists and exiles” was a success. The Stasi had been "tricked".

Illegality and repression

Everyone involved knew that what they were doing was illegal. Official environmental data was inaccessible and had to be treated as " confidential classified information " since 1972, and as "secret classified information" since 1982. The resolution of the Council of Ministers on the protection of environmental information of November 16, 1982 and two documents from 1984 on implementation, all themselves classified as "Confidential Information ", were first published by Arche Nova in the 2nd edition of October 1988.

According to Section 219 of the Criminal Code (“ Illegal connection ”) , “anyone who disseminates or lets disseminate messages abroad that is likely to harm the interests of the GDR or produces or has records made for this purpose ” could be punished with several years imprisonment "Whoever surrenders or has surrendered writings, manuscripts or other materials which are likely to harm the interests of the GDR, by circumventing legal provisions, to organizations, institutions or persons abroad”. The environmental data, according to the logic of criminal prosecution, would be used by the class enemy to discredit the GDR. Also into consideration were charges of “ forming an association to pursue unlawful goals ” (Section 218), “ treasonous messaging ” (Section 99) or “treasonous agent activity” (Section 100), because of the civil rights activists Wolfgang Templin , Stephan Krawczyk and Freya in January 1988 Klier had been charged. Because of anti-state propaganda (§ 106) Western journalists could be prosecuted.

The GDR citizens of the team had to reckon with a much higher punishment than the West German members if the conspiratorial project was exposed through spies, gossip or mistakes on the day of shooting. Neumann later judged: “That was dangerous. That could have cost us many, many years physically and mentally. ”Zimmermann said:“ There was somehow the awareness to do something that some people might not have completely agreed with. ”Wallisch estimated:“ Ten, twelve Years imprisonment - that would have been quite normal for the time. "

The cameraman Hällfritzsch initially hesitated. “I've already thought about whether the thing is worth six months or a year in prison,” he later recalled, but because the conditions had been described to him so drastically, he ultimately “thought it was good to be there what would do. "Miosga, on the other hand, was certain:" Even if I am arrested there, sooner or later I will be ransomed by my state, taken out [...] They did not book me away for two years. "

In June 1989 Jörg Klöpzig killed himself and his little daughter in the Lada on a landfill. Previously, the Stasi had repeatedly interrogated him and put him under pressure because of his environmental opposition activities. A direct involvement of the Stasi in his death could not be proven. "Whether a private tragedy or official tutoring was given, or whether it was both in the end - nobody knows until today," wrote Ulrich Neumann in 1995.

Post production and distribution

The cassette with the raw material initially stayed in East Berlin. Wallisch gave them to Falk Witt, a medical technician from West Berlin who was familiar to him and who had completed an assignment at the Charité and only found out about the content of the material later. Witt handed the cassette in West Berlin to Neumann, who had been able to leave the GDR at the end of June. In the WIM studio, Hällfritzsch, Miosga and Neumann edited and set the film to music in the evenings and at night in order to keep the circle of confidants small.

Four VHS copies of the finished 30-minute film were sent to the East by courier . The Arche activists and the filmmakers had agreed to show bitter from Bitterfeld first in the GDR. The film should be considered as produced there by the ark , in order not to be discredited as television propaganda adopted from the West. For their part, the GDR opposition wanted to avoid the impression that they were working with the West.

Radiance and finances

Neumann got in touch with Kontraste editor Peter Wensierski . Although the editors feared the closure of the ARD office in East Berlin, they decided to broadcast the report on September 27, 1988 and to advertise it intensively beforehand. The half-hour documentary resulted in a ten and a half minute contribution, which consisted of eight minutes of the original and an interview with Uli Neumann, who had been living in West Berlin for a few weeks. Moderator Jürgen Engert announced a “film premiere that could very well take place on Soviet television, but not, not yet, on GDR television.” The documentary is “proof that the environmental protection movement, born from very small beginnings, in The GDR is in the process of forming a counter-public. ”For the editorial team of Kontraste , the film report was later one of the important contributions, the times rich in contrasts in the overview presentation. 40 years from the life of a political magazine have been depicted.

From West Berlin, Neumann sold the pictures to TV stations all over the world. She also took over the ZDF television magazine Kennzeichen D. The broadcast of excerpts on RIAS-TV in December 1988 was “generously” rewarded in the knowledge that the proceeds went to the ark. From the proceeds and prize money from Vital magazine . Print material, computers and video equipment for new “Arche” productions were purchased for DM 10,000. Arche member Falk Zimmermann received the camera. The Berliner, later exposed as an unofficial employee of the Stasi, sabotaged important projects by simulating errors in image and sound recordings.

The magazine Arche Nova

When the film was still being planned, the Arche activists had already decided to make the Bitterfeld location the focus of their samizdat magazine Arche Nova . Issue 1 appeared immediately before the film's shooting day and contained information that was also used for the captioning of the film. On the day of the Kontraste broadcast , the taz published the main text on a full page. In issue 2, Jörg Klöpzig published a report on the derivation of the magnesium chloride solution with which the amber particles were washed out of the earth in the Goitzsche opencast mine. In issue 3, two articles mocked the reactions of government agencies to the broadcast of the Kontraste contribution.

Facts and mistakes

Monika Maron made Bitterfeld known as the “dirtiest city in Europe” with her novel Flugasche . Deviating from the quote in the film, Maron only names the city “B.” in the book . The book was published in 1981 by S. Fischer Verlag in Frankfurt am Main and not in the GDR because it did not show the “positive consequences of work for people” . In fly ash, Maron addresses the emissions of an outdated lignite power plant; however, the film does not deal with the power plant. In the GDR, fly ash became known about 100 free copies that Fischer sent the author and that she distributed to readers. Ulrich Neumann presented longer quotations from the paperback first edition of fly ash as a “book telegram” in volume 1 of Arche Nova , which had a focus on Bitterfeld . Maron left the GDR on June 3, 1988 with a three-year visa.

The film speaks of 23,000 employees “in the factories”. According to information from 2010, 45,000 people were employed in the three Bitterfeld combines, apart from the external works. 18,000 people worked in the Bitterfeld Chemical Combine (CKB), which was created in 1969 from the Bitterfeld Electrochemical Combine (EKB) and the Wolfen paint factory. The ORWO Wolfen photochemical combine, founded in 1970 with the Wolfen film factory as the parent company, had 15,000 employees and the Bitterfeld brown coal combine (BKK), established in 1968, had 12,000 employees. In 1988 almost 21,000 people lived in Bitterfeld and 46,000 in Wolfen.

On June 17, 1953, protests also broke out in Bitterfeld. A 25-member strike committee represented 30,000 workers on strike and had the city administration, police, the MfS building and other state facilities occupied. Even when Soviet troops intervened, there were no riots.

The "phenyl chloride disease" with the regression of the finger bones is correctly called vinyl chloride disease , an acroosteolysis . The "fluorosis" with bone proliferation in joints is a bone fluorosis ; Fluorides can be released during aluminum electrolysis, for example. The "graphite diseases" are graphitoses, especially graphite fibrosis . Graphite can be released during the manufacture of electrodes .

The number of deaths from the vinyl chloride explosion in Bitterfeld on July 11, 1968 is usually given as 42. The number of 68 victims mentioned in the film is already included in the first issue of Arche Nova ("over 68 deaths") without any evidence .

| Landfills in the Bitterfeld district (selection) |

Volume million m³ |

content |

|---|---|---|

| Landfill Hermione | 20th | Ash, asbestos , heavy metals |

| Freedom III special landfill | 2 | Industrial sludge, ash, rubble |

| Pit Johannes ("Silbersee") | 5 | Sludge (heavy metals, CHC ) |

The pit with pipeline feed, not named in the film, is the Hermine rinsing dump . A total of four pipelines carried dissolved ash and production sludge from the film factory and power stations of the CKB and “flushed” them into the pit lake of the former mining hole. The high-rise shown is the tallest building in the Neue Heimat housing estate in Sandersdorf, which was completed in 1968 . In 1992 the quantitative environmental pollution of the region was published, including the characteristics of the three landfills visited (see table) .

The Goitzsche contained an amber deposit with an estimated content of 1,800 tons. Between 1975 and 1990, 408 tons of this were mined industrially. The VEB Ostsee-Schmuck in Ribnitz-Damgarten was responsible , which also exported its articles to the West and had been supplied from the Soviet Union until the 1970s . Buyers of “Baltic jewelry” in the west had no way of knowing whether their amber came from the Baltic coast or from Bitterfeld. This would also be irrelevant if both find regions were fed by the same amber forest; the thesis is controversial among scientists. The USSR delivered up to ten tons a year; Almost 50 tons came from Bitterfeld in the record year 1983. Lack of profitability and environmental pollution ended the mining in 1993. The flooding of the Goitzsche stopped the forbidden private excavations.

The granary shown in the film is today's warehouse of Wittenberger Agrarhandel GmbH , which belongs to Roth Agrarhandel GmbH in Kirchhain in Hesse . The chlorine electrolysis plant Chlor IV, which went into operation in 1981, not far from the storage facility, was demolished in 1997. The newly built plant is now part of AkzoNobel Industrial Chemicals. The granary with a volume of 36,000 tons was certified in 2003 for the storage of 10,000 tons of organic grain.

Reactions in the GDR

population

The broadcast on western television became a street talk in the Bitterfeld region. "The broad impact of the broadcast is unmistakable," wrote the Stasi object service office of the CKB. “We all saw it, more or less,” remembers the chemical technician Bernhard Roth. The chemical laboratory technician Ursula Heller said: “That shook me.” MfS offices found that “a large number of the residents characterized the program as a measure (sic) to arouse fear and insecurity among the population.” Two Arche activists wrote 1992 that the people of Bitterfeld "only perceived their own, immediate reality of life when they (...) had it (...) delivered to their living room via Western television." In 2005, Hans Zimmermann said in retrospect: "We have reached the people." In 2010, the Tagesspiegel read: “Back then, Zimmermann changed the city, maybe a bit of the world.” However, Zimmermann himself registered “only a brief flicker of passions”. The US-American environmental economist Merrill E. Jones saw a threefold effect in 1993: the audience received previously inaccessible environmental information, learned of the existence of the environmental protection movement in the GDR and saw a successful campaign against the authorities.

Siegfried Burschitz, then project manager at the CKB, was not surprised by the statements made in the film, "because we (...) knew this problem." On October 25, 1988, the program Radio Glasnost broadcasted from West Berlin and sent by GDR opposition members broadcast audience reactions . A resident from Friedersdorf judged: "In places it is much worse than what is transmitted in the video." He complained about the ignorance of the Bitterfelder about the environmental damage. Civil rights activist Friedrich Schorlemmer said: “It was only through this film on western television that we noticed how bad it really is for us, we were so used to the conditions. We needed this mirror that was held up to us to finally wake up completely. "

Church and environmental movement

The video was “perhaps the most spectacular action by GDR environmental groups”. Its premiere in the East Berlin Environmental Library put an end to the "enmity" between the Arche and the Environmental Library. The Stasi registered through reports from unofficial employees when and where the video was shown, for example on September 21 in East Berlin and then in Altenberg near Dresden . In Bitterfeld the performance failed because the messenger had a flat tire.

"The harrowing film about environmental destruction on an apocalyptic scale caused a sensation," wrote the news magazine Der Spiegel in retrospect. Contrasts received further indications of grievances. The civil rights activist Hans-Jürgen Fischbeck noted more willingness to criticize, “because you saw: people had the courage to risk their existence and make such a film.” Wallisch had the impression “that it has given many environmentalists courage, to continue. "The submission of a citizen from Freiberg in Saxony from October 2nd, 1988, who took the abuses denounced in the film as an opportunity to" point out similar environmental sins in the Freiberg area. "

The program met with isolated rejection in critical circles. Pastor Hans-Peter Gensichen , head of the church research home in Wittenberg , thought the Arche's educational approach was too aggressive and found that the network had misused the research home as a cover for the preparation of the Arche Nova magazine . Many members of the opposition felt that the use of Western television was "an 'actionist' fixation on the media effectiveness of the Ark work and a 'self-expression'".

Government agencies

With regard to the authorities, Ulrich Neumann considered the film and the television broadcast to be successful. "The effect of bitter from Bitterfeld was exactly as I had imagined: that it was a bomb for the comrades in Bitterfeld, in Halle, in Berlin and they didn't even know what happened to them," he said in 2005. Lieutenant Colonel Peter Romanowski from the MfS district administration in Halle stated that there was “a lot of excitement”. Hans Zimmermann knew from hearsay: "The Stasi headquarters, which was organized in the CKB, was upside down, it was all going on." In the plant, "an insane cleaning" started. So the Freedom III landfill was closed with bulldozers and a lot of earth.

On September 30th, a working group made up of MfS agencies presented a seven-page “Situation Assessment - Environmental Pollution in the Bitterfeld District”. It contained details about the "sometimes extreme pollution of the atmosphere", "serious health-damaging pollution of people" and a water quality of the hollow "which makes any subsequent use impossible." The entries were "justified in the majority of cases." The authors are not satisfied with general answers and promises. As early as 1987, MfS offices had pointed out in detail acute dangers in the production of chemicals.

The Basic Industry Department at the Central Committee of the SED had to prepare a statement for Günter Mittag , Central Committee Secretary for Economics, and met on October 5th. Emissaries from the CKB pointed out that there were neither violations of the law nor violations of the “operating regime” - the correct use of technology - at the landfills. There is a high level of operational order in terms of recording and documentation. The chlorine production at the granary is environmentally friendly, the " nitrosamine problem" has been addressed but not discussed. The protocol called "Line Information" also contained a list of problems.

Outwardly, the film's criticism should be rejected. From October comes a "plan of action for targeted counter-arguments against the ARD television program about environmental protection in Bitterfeld". Most of his eight points, however, dealt with immediate measures to reduce the environmental impact, instructions and technical controls in the factories. Officials denied to Western journalists that the pictures came from Bitterfeld or that life expectancy was lower. The chairman of the council of the Halle district, Alfred Kolodniak , promised: "Bitterfeld is not yet a climatic health resort, but it is on the way there." The environmental protection department of the council of the Bitterfeld district put together "arguments". Reference was made to "the scandals in the FRG, where uncontrolled toxins are dumped and where even landfills are given as building land for homes."

In East Berlin, the spy Falk Zimmermann, who worked in the Arche network, suspected after the broadcast that Neumann and Wallisch were behind the show. He hadn't found out anything before. In a discussion after the fall of the Wall, Zimmermann said that his commanding officers wanted to "tear his ears off his head" because of this. In Bitterfeld, Hans Zimmermann, who was noticed by his petitions, was targeted by investigators. But in the increasingly uncertain domestic political situation, nothing happened.

The state power was not aware of any participation from the West. The Central Evaluation and Information Group (ZAIG) of the MfS, in which the "countless reports" of the Stasi employees flowed together, dated June 1, 1989, wrote a top secret "information". With her she informed the 15 top functionaries of the party and state leadership about the "becoming effective" of the opposition. In the section on basic church groups it says: "There are first indications about the use of video technology (video film 'Bitteres from Bitterfeld')." In the section on the ark it is stated that its "powers" for the "production and distribution of the video" to be responsible.

The GDR television responded on October 5th with the broadcast of the hastily produced contribution Tippeltips from Bitterfeld for hikers, in which "the destroyed region as a local recreation area" was shown. "According to exact recultivation plans, a landscape was designed that has its very own charm," the article said. The contribution “at prime time”, for which “the council of the district and other environmental protection agencies really beat the drum”, showed no house or tree up close. "You could just spot Bitterfeld by the chimneys!"

On October 7th, GDR television shot in Bitterfeld, reported the October issue of Arche Nova in an ironic article. But no second part of Bitteres from Bitterfeld is produced. The filmmakers, it was said, citing "members of the rotating staff", needed soot-blackened houses and completely neglected-looking streets to shoot an episode of the school television series English for you . The sequence will be broadcast under the title In the slums of London .

Significance and development from 1989

The images in the film in 1988 astonished television viewers in the West because of their glaring visuality. The turnaround has "further intensified the media thematization of Bitterfeld as an ecological emergency area, which almost amounted to stigmatization," wrote the historian Amir Zelinger. Journalists from all over the world visited Hans Zimmermann and asked him about the locations in the film. In 1990 a government commission examined the situation in Bitterfeld comprehensively. For the first time in Germany, a chemical region was examined in such detail. The officials' previous denials turned out to be false. The situation was worse than depicted in the film. The publication of MfS documents in particular showed that the officials in the plant, authorities and party were aware of the health and environmental pollution without drawing any conclusions from it.

In the 1990s, the Treuhandanstalt had most of the CKB's facilities closed and demolished. The air quality improved significantly, the landfills were renovated or, in order to prevent contact with the groundwater , encapsulated and greened. The flooding of the Goitzsche from 1998 to 2002 created an ecological picture of the former industrial areas, which the cultural historian Gerhard Lenz called "water landscapes of oblivion". Despite the establishment of the Bitterfeld-Wolfen Chemical Park, unemployment remained high. The Bitterfeld solar industry with 4,000 jobs in the peak year 2008 and a further 4,000 at suppliers in the region has lost its importance after the bankruptcy of many companies. The solar cell manufacturer Q-Cells was temporarily the largest industrial employer in the district.

Since the 1990s, further feature films have been made about the location. This includes a five-part TV documentary cycle by director Thomas Füting . It began in 1993 with And what's up from the ruins? Bitterfeld sketches and ended in 2005 with a reunion in Bitterfeld - 15 years in the new Germany . In the same year the making-of “That was bitter from Bitterfeld” was created for MDR , which represented the creation of “bitter from Bitterfeld”. In 2001, the “polemical essay” Bitterfeld, in 1992 by the Swiss director Mathias Knauer, was controversial . The documentation The Industrial Garden Realm dealt with the historical mix of heavy industry and garden art . Wörlitz, Dessau, Bitterfeld from 1999.

The film title Bitteres from Bitterfeld became independent as a heading for articles about local problems. The noun "bitter" was used in scientific journalism dealing with the region.

Remaining hole Goitzsche, behind the Bitterfeld amber villa , 1991

Versions and making-of

- The 30-minute original version was shown on VHS cassettes in the GDR in church parishes and other opposition circles in 1988. The original version was shown for the first time in Germany at the 6th Kassel Documentary Film and Video Festival in December 1989.

- The article in the ARD magazine Kontraste of September 29, 1988 with a length of ten and a half minutes was by Peter Wensierski and, in addition to the original recordings, contained an interview with Ulrich Neumann, who had already traveled to West Berlin.

- For the US Environmental Film Festival in Santa Monica in 1991 a 30-minute version was cut and retexted under the title The Bitter Winds Of Bitterfeld on high-band SP . It now also contained an interview in which Hans Zimmermann reported on the circumstances surrounding the shooting. The German / English language film was financed with a grant from the European Parliament .

- The WIM media workshop, in cooperation with Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk, produced a 45-minute documentary about the making of bitter from Bitterfeld on Betacam SP under the title Das war Bitteres from Bitterfeld . Rainer Hällfritzsch, Ulrike Hemberger and Margit Miosga directed the film. It was first broadcast on March 7, 2006. In 2009, the Federal Foundation for Work-Up published this film on DVD, expanded to include accompanying material for use in school lessons. The Japanese TV station NHK broadcast a dubbed version of this making-of in 2009 .

Awards

- 1989 Environment Prize, Vital magazine , Hamburg

- 1990 Special Prize, Ökomedia '90, Freiburg

- 1991 Award "Magna cum laude", Medikinale International Parma (MIP)

- In 1999 film clips were included in the permanent exhibition of the Leipzig Contemporary History Forum

- 2011 inclusion of Bitteres from Bitterfeld and Das war Bitteres from Bitterfeld in the mediaartbase at the Center for Art and Media Technology (ZKM) in Karlsruhe

Web links

- Bitterfeld photos from the Federal Archives on Wikimedia Commons

- Video: Peter Wensierski's contribution on the film Bitteres from Bitterfeld , length: 10'32 ″, in: Kontraste , September 29, 1988, online , accessed on March 29, 2013. - Verbatim transcript of the broadcast in: Landeshauptarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt, Merseburg department , online , accessed March 29, 2013

- Video: "That was the principle of self-defense". Interview with Hans Zimmermann, length: 10'23 ″, broadcast on MDR April 12, 2010, online , accessed on March 9, 2013

- Website of the workshop for intercultural media work , accessed on April 27, 2013

Individual evidence

The references in the films are given after the minute and second of the time code , quotations under three seconds only start at the beginning. The following are abbreviated:

| Abbreviation | Full title |

|---|---|

| BaB | Bitter from Bitterfeld. An inventory. Film, directors: Rainer Hällfritzsch, Margit Miosga, Ulrich Neumann. 30 minutes, FRG 1988 |

| DW | That was bitter from Bitterfeld. Film, directors: Rainer Hällfritzsch, Ulrike Hemberger, Margit Miosga. 45 minutes, Germany 2005 |

| J / K | Carlo Jordan, Hans Michael Kloth (Ed.): Arche Nova. Opposition in the GDR. The “Green-Ecological Network Arche” 1988–1990. Basis-Druck, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-86163-069-9 (= Basis-Druck -Dokument d17 ) |

- ↑ BaB , e.g. B. 3'35 ", 4'48". Images online , accessed March 30, 2013.

- ↑ BaB , 28′02 ″

- ↑ J / K, p. 81 f.

- ↑ J / K, p. 183. DW , 2'39 ″ –7′02 ″

- ↑ DW , 7'19 ″ -8'37 ″

- ^ Dieter Daniels, Jeannette Stoschek: Gray area 8 mm. Materials on the autonomous artist film in the GDR. Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-1955-1 , p. 110. Christian Hoffmann: Left next to television. Independent video productions from the GDR can be seen in Kassel. In: the daily newspaper. December 7, 1989.

- ^ Dieter Daniels, Jeannette Stoschek: Gray area 8 mm. Materials on the autonomous artist film in the GDR. Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-1955-1 , p. 16.

- ↑ a b Chris Humbs, Jan Jansen: Times rich in contrast. 40 years from the life of a political magazine. RBB media, December 15, 2008, 19′45 ″ –20′48 ″

- ↑ Alexander Seibold: Catholic film work in the GDR. Lit-Verlag Münster 2003 (= Diss. Gießen 2002), ISBN 3-8258-7012-X , pp. 59-61. Christian Hoffmann: To the left of the television. Independent video productions from the GDR can be seen in Kassel. In: the daily newspaper. December 7, 1989.

- ↑ DW. 25'26 ″

- ↑ DW , 10′50 ″ –11′47 ″

- ↑ Program of Saturday, June 25, 1988, online , accessed on March 15, 2013.

- ↑ DW , 10'35 "–10'50"

- ↑ a b Karl-Heinz Baum: When Ruud Gullit kicked and the Stasi was tricked. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. April 10, 1995.

- ↑ DW , 11'50 "-12'30". J / K, p. 90.

- ↑ J / K, p. 90.

- ↑ J / K, p. 90.

- ↑ a b German Bundestag: Materials of the Enquete Commission 'Overcoming the Consequences of the SED Dictatorship in the Process of German Unity'. Nomos-Verlag Baden-Baden 1999, ISBN 3-7890-6354-1 , Volume 8, Part 2, p. 1483.

- ↑ DW , 8'39 ″ -8'50 ″

- ^ Rainer Karlsch: Uranium for Moscow. The bismuth - a popular story. Christoph Links Verlag, 3rd edition. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-427-3 , p. 195.

- ↑ J / K, pp. 269-274.

- ↑ See also: Johannes Raschka: Judicial Policy in the SED State. Adaptation and change of criminal law during Honecker's tenure. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-412-06700-8 , pp. 152-164.

- ^ Anja Hanisch: The GDR in the CSCE process 1972–1985. Oldenbourg, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-71351-0 , p. 223. - A compilation of criminal offenses against the political opposition in: Frank Joestel (Ed.): Criminal prosecution of political opponents by the state security im 1988. The last annual report of the Stasi investigation department. Berlin 2003, p. 109 f.

- ↑ DW , 16′42 ″ –16′47 ″, 10′18 ″ –10′28 ″

- ↑ DW , 10′02 ″ -10′11 ″

- ↑ DW , 14'36 "-14'43"

- ↑ DW , 14′44 ″ -15′02 ″

- ↑ DW , 11′12 ″ –11′47 ″

- ↑ DW , 16'58 ″ -17′15 ″

- ↑ J / K, S. 90. Ehrhardt Neubert: History of the opposition in the GDR 1949-1989. Christoph Links Verlag, 2nd edition. Berlin 1998 (= Diss. Berlin 1997), ISBN 3-89331-294-3 , p. 652.

- ↑ DW , 28′40 ″ –29′34 ″

- ↑ DW , 00′06 ″ -00′14 ″, 33′59 ″ -34′09 ″. See also: Chris Humbs, Jan Jansen: Times rich in contrast. 40 years from the life of a political magazine. DVD, RBB media, December 15, 2008, 19′45 ″ –20′48 ″

- ^ Merrill E. Jones: Origins of the East German Environmental Movement. In: German Studies Review. Volume 16, Issue 2 (1993), p. 257.

- ↑ a b Heidi Mühlenberg, Michael Kurt: Panikblüte. Bitterfeld report. Forum Verlag, Leipzig 1991, ISBN 3-931801-15-2 , p. 91.

- ↑ DW , 40′42 ″ -42′08 ″

- ↑ "Traveler, who you are coming to Bitterfeld ...". In: the daily newspaper. September 27, 1988.

- ↑ Jörg Klöpzig: Bitterfeld: Additional pollution of the water. In: Arche Nova 2, October 1988. Reprinted in: J / K, pp. 281 f.

- ↑ See #Government agencies

- ↑ Monika Maron: Fly ash. Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-596-22317-2 , p. 32.

- ↑ Ann-Kathrin Reichardt: The censorship of fiction literature in the GDR. In: Ivo Bock (Ed.): Sharply monitored communication. Censorship systems in Eastern (Central) Europe (1960s - 1980s). Lit Verlag Dr. W. Hopf, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-11181-4 , p. 405.

- ↑ Katharina Boll: Memory and Reflection, retrospective life constructions in the prose work of Monika Marons. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2002, ISBN 3-8260-2325-0 , p. 19, note 44

- ↑ Stefan Pannen: The Forwarders. Function and self-image of East German journalists. Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-8046-0338-6 , p. 117.

- ↑ BaB , 25′07 ″

- ↑ International Building Exhibition, Urban Redevelopment Saxony-Anhalt 2010. Bitterfeld-Wolfen, p. 12, PDF ( Memento from December 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on March 25, 2013. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Chemiestandort Ostdeutschland. Structural and industrial policy action required for economic and ecological renovation, Bonn 1991, online , accessed on March 25, 2013.

- ^ List of the largest cities in the GDR

- ↑ Ehrhardt Neubert: History of the Opposition in the GDR 1949–1989. Christoph Links Verlag, 2nd edition. Berlin 1998 (= Diss. Berlin 1997), ISBN 3-89331-294-3 , p. 85.

- ^ Council of the district of Bitterfeld: argumentation material for the program Kontraste on 09/27/1988. Letter dated November 9, 1988. State Main Archives Saxony-Anhalt, Merseburg Department, M Council of the Halle District, 4th ed. No. 6572, p. 40, online , accessed on March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Wolfgang Dihlmann: Joints - vertebral connections. 3. Edition. Stuttgart, New York 2002, ISBN 3-13-132013-3 , p. 67.

- ↑ Yearbook Ecology 2002, Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2002, quoted from: Michael Zschiesche: Die Luft - ein Gasfeld. In: Friday. November 30, 2001, online , accessed March 25, 2013. Michael Zschiesche: Explosionen in Bitterfeld. In: Listen and Look. Issue 76 (2012), pp. 20–24, online ( Memento from March 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 384 kB), accessed on April 16, 2013. The Bitterfeld catastrophe. MDR, February 12, 2013, accessed March 25, 2013.

- ↑ BaB , 15'58 ″

- ↑ J / K, p. 198.

- ↑ a b Hans-Joachim Köhler u. a .: Concepts and priorities for action to secure and clean up old deposits, landfills and groundwater in the greater Bitterfeld / Wolfen area. In: Josef Hille u. a. (Ed.): Bitterfeld: Exemplary ecological inventory of a contaminated industrial region. Contributions from the 1st Bitterfeld Environmental Conference. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 1992, pp. 203-210. Quoted from Annegret H. Thieken: Pollutant patterns in the regional groundwater contamination of the central German industrial and mining region Bitterfeld-Wolfen. Diss. Halle-Wittenberg 2001, ISBN 3-8364-7039-X , urn: nbn: de: gbv: 3-000003928 , online , accessed on April 15, 2013.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Synnatzschke: Historical from Sandersdorf-Brehna. Remediation of brown coal mines left behind, online , accessed on April 15, 2013, with a sketch of the location

- ↑ Zeittafel Sandersdorf-Brehna, http://www.anhaltweb.de/zeittafel-41x28x0x0x2x35x28x26x.html ( Memento from December 4, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) , accessed on April 15, 2013.

- ↑ Roland Wimmer u. a. (Ed.): Bitterfeld Bernstein: Deposits, raw material, subsequent use. I. Bitterfeld Amber Colloquium (= EDGG, Issue 224, 2005). Roland Wimmer u. a. (Ed.): Bittersteiner amber versus Baltic amber - hypotheses, facts, questions. II. Bitterfeld Amber Colloquium. (= EDGG, issue 236, 2008)

- ↑ Roland Fuhrmann: Origin, discovery and exploration of the Bitterfeld amber deposit. In: Roland Wimmer u. a. (Ed.): Bitterfeld Bernstein: Deposits, raw material, subsequent use. I. Bitterfeld Bernstein Colloquium (= EDGG, Heft 224, 2005), pp. 25–35. Carsten Gröhn: Amber Adventure Bitterfeld. Book on Demand, Norderstedt 2010, ISBN 978-3-8391-1580-0 , pp. 72-75, 85 f.

- ^ AkzoNobel Industrial Chemicals - Bitterfeld plant. Our story, online ( Memento from June 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on March 22, 2013.

- ↑ Location profile of Roth Agrarhandel GmbH, online , accessed on March 22, 2013.

- ↑ DW , 37'17 ″

- ↑ DW , 0′40 ″

- ↑ DW , 34'50

- ^ [Ministry for State Security] BV Halle, KD Bitterfeld, OD CKB: Assessment of the situation - environmental pollution in the district of Bitterfeld from September 30, 1988. Printed in: Hans-Joachim Plötze: The chemical triangle in the Halle district from the perspective of the MfS. Without location, September 1997, p. 101 (= contributions in kind (4), published by the state commissioner for the records of the state security service of the former GDR in Saxony-Anhalt)

- ^ Carlo Jordan, Hans Michael Kloth: Introduction. In: J / K, p. 184.

- ↑ DW. 34'32 ″

- ^ Thomas Trappe: Bad Bitterfeld. In: Der Tagesspiegel. November 7, 2010, online , accessed April 21, 2013.

- ^ Merrill E. Jones: Origins of the East German Environmental Movement. In: German Studies Review. Volume 16, Issue 2 (1993), p. 256 f.

- ↑ DW , 35′05 ″ -35′17 ″

- ^ Bitter from Bitterfeld. Video, sound file with black and white images, length: 47 ″, online , accessed on March 24, 2013.

- ^ A b Nikolaus von Festenberg: Image pirates of freedom. In: Der Spiegel. September 29, 2008, online , accessed March 31, 2013.

- ↑ Lars-Broder Keil , Sven Felix Kellerhoff : Rumors make history. Christoph Links Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-86153-386-3 , p. 221.

- ^ Matthias Voigt: forceps delivery under the church roof. In: the daily newspaper. May 4th 1990.

- ↑ DW , 29'35 ″ -30′18 ″. Hans-Joachim Plötze: The chemical triangle in the Halle district from the perspective of the MfS. Contributions in kind (4), published by the State Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR in Saxony-Anhalt. OO, September 1997, p. 104.

- ↑ DW , 35′45 ″ -36′00 ″

- ↑ DW , 43′17 ″ -43′23 ″

- ^ Text accompanying the publication, Landeshauptarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt, Merseburg Department, M Council of the Halle District, 4th ed. No. 6572, sheet 205, online , accessed on March 28, 2013.

- ↑ J / K, p. 183 f. See also: Hans-Peter Gensichen: The contributions of the Wittenberg research home for the critical environmental movement in the GDR. In: Hermann Behrens, Jens Hoffmann (Hrsg.): Environmental protection in the GDR. Analyzes and eyewitness reports, Volume 3: Professional, voluntary and voluntary environmental protection. Oekom-Verlag Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-86581-059-5 , pp. 149-177.

- ↑ J / K, p. 184.

- ↑ DW , 43′00 ″ -43′16 ″

- ↑ DW , 36′20 ″ -36′56 ″

- ^ [Ministry for State Security] BV Halle, KD Bitterfeld, OD CKB: Assessment of the situation - environmental pollution in the district of Bitterfeld from September 30, 1988. Printed in: Hans-Joachim Plötze: The chemical triangle in the Halle district from the perspective of the MfS. Ohne Ort, September 1997, pp. 97-105 (= contributions in kind (4), published by the State Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR in Saxony-Anhalt)

- ↑ Printed in: Hans-Joachim Plötze: The chemical triangle in the Halle district from the perspective of the MfS. Without place, September 1997, pp. 36–48, 83–91 (= contributions in kind (4), published by the state commissioner for the records of the state security service of the former GDR in Saxony-Anhalt)

- ^ Inspection of work and production safety: Line information , October 5, 1988. Landeshauptarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt, Merseburg Department, M Council of the Halle District, 4th ed. No. 6572, p. 309, online , accessed on March 28, 2013.

- ^ Inspection of work and production safety: Line information , October 5, 1988. Landeshauptarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt, Merseburg Department, M Council of the Halle District, 4th ed. No. 6572, Bl. 309-311, online , accessed on March 28, 2013.

- ↑ Without author: Action plan for targeted counter-arguments to the ARD television program on environmental protection in Bitterfeld, [October 1988]. State Main Archive Saxony-Anhalt, Merseburg Department, M Council of the Halle District, 4th OJ. No. 6572, Bl. 288–290, online , accessed on March 28, 2013.

- ↑ DW , 38'32 ″ -38'58 ″

- ↑ Peter Maser: Faith in Socialism. Verlag Gebr. Holzapfel, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-921226-36-8 , p. 131.

- ^ Council of the district of Bitterfeld to the council of the district of Halle: argumentation material for the program 'Kontraste' on 09/27/1988. November 9, 1988. State Main Archive Saxony-Anhalt, Merseburg Department, M Council of the Halle District, 4th ed. No. 6572, p. 40 f., Online , accessed on March 28, 2013.

- ↑ J / K, p. 64.

- ↑ DW , 39′13 ″ -40′40 ″. Ehrhardt Neubert: History of the opposition in the GDR 1949–1989. Christoph Links Verlag, 2nd edition. Berlin 1998 (= Diss. Berlin 1997), ISBN 3-89331-294-3 , p. 752.

- ↑ Armin Mitter, Stefan Wolle (ed.): I love you all! Orders and situation reports of the Stasi, January – November 1989. 2nd edition. BasisDruck Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 1990, p. 9. Bitteres from Bitterfeld is not mentioned in the central reporting of the MfS in 1988 . Cf. Frank Joestel (ed.): Criminal prosecution of political opponents by the State Security in 1988. The last annual report of the MfS main investigation department. Berlin 2003. Frank Joestel: The GDR in the eyes of the Stasi. The secret reports to the SED leadership in 1988. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-525-37502-0 (CD-Rom)

- ↑ Armin Mitter, Stefan Wolle (ed.): I love you all! Orders and situation reports of the Stasi, January – November 1989. 2nd edition. BasisDruck Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 1990, p. 60.

- ↑ Armin Mitter, Stefan Wolle (ed.): I love you all! Orders and situation reports of the Stasi, January – November 1989. 2nd edition. BasisDruck Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 1990, p. 68.

- ↑ Excerpt in DW , 38′18 ″ –38′30 ″. J / K, p. 183.

- ↑ Anonymous: Bitterfeld. The current cultural criticism! In: Ark Nova. 3, February 1989, p. 67. Also reprinted in: J / K, p. 352 f.

- ↑ Anonymous: Information and correction. In: Ark Nova. 3, February 1989, p. 68. Reprinted in: J / K, p. 353. See also: Hans-Michael Kloth: The quiet terror of the later years. In: Der Spiegel. September 20, 1999, online , accessed March 30, 2013.

- ↑ Amir Zelinger: Bitterfeld. In: Ecological places of remembrance. Website of the Rachel Carson Center, Munich, online , accessed April 27, 2013.

- ↑ DW , 43'43 "–43'56"

- ↑ DW , 42′12 ″ -42′58 ″

- ^ Gerhard Lenz: Loss experience landscape. About the creation of space and the environment in the central German industrial area since the middle of the 19th century. Campus, Frankfurt am Main, New York 1999, ISBN 3-593-36255-4 , p. 206.

- ^ Benjamin Nölting: New Technologies and Real Growth. How the company Q-Cells created a solar cluster in Central Germany with regional associations near Bitterfeld. In: Christoph Links, Kristina Volke (Ed.): Inventing the future. Creative projects in East Germany. Christoph Links Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86153-542-3 , p. 49.

- ^ Ulrich Bochum, Heinz-Rudolf Meißner: Solar industry: photovoltaics. OBS working paper No. 4. Otto Brenner Foundation, Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 49.

- ↑ Elke Schulze: Warm rain. In: stern.de. September 22, 2008, online , accessed April 29, 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Füting: And what comes out of the ruins? Bitterfeld sketches . Film, 60 minutes, 1993. Reviewed by Barbara Sichtermann : With and without soft image. In: The time. December 10, 1993, online , accessed March 24, 2013.

- ^ Thomas Füting: Reunion in Bitterfeld - 15 years in the new Germany. Film, 120 minutes, MDR 2005. Reviewed by Paul Ingendaay : The baby from back then. Fourteen-year film: Thomas Füting shows how the people in Bitterfeld hold their own. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. September 30, 2005.

- ^ Film description, online , accessed March 24, 2013.

- ↑ Bitterfeld, 1992 . Director: Mathias Knauer, Film, 112 minutes, Switzerland 2001. - Mathias Knauer: Information and notes on “Bitterfeld, 1992”, online (PDF; 74 kB), accessed on March 24, 2013. Meetings online (PDF; 34 kB) , accessed on March 24, 2013. Duisburg protocols. Duisburg Film Week 2001 , online (PDF; 30 kB), accessed on March 24, 2013.

- ↑ Niels Bolbrinker, Manfred Herold: The industrial garden realm. Wörlitz, Dessau, Bitterfeld . Film, 100 minutes, video cassette, absolut media, Berlin 1999.

- ↑ Peter Wensierski: Bitter from Bitterfeld. Oppressed, blackmailed, spied on: the environmental initiatives in the SED state. In: Spiegel special. February 1, 1995, online , accessed on April 16, 2013. M. Schulze: Bitteres from Bitterfeld. In: VDI-Nachrichten. July 5, 1996. Christian Geinitz: Bitter from Bitterfeld. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. July 15, 2009. Viktoria Bittmann: Bitter truths from Bitterfeld. In: Märkische Allgemeine. March 10, 2012, online , accessed April 16, 2013.

- ↑ Michael J. Ziemann: Bitter legacy of 'achieved socialism'. Paper über das Chemiedreieck, Seattle Pacific University, undated (1997?), Online ( MS Word ; 194 kB), accessed on April 15, 2013

- ^ WIM film catalog, online , accessed on March 28, 2013.

- ↑ mediaartbase, online search mask