Irreducible complexity and Andreas Vesalius: Difference between pages

Dave souza (talk | contribs) Undid revision 245010033 by OneBillionthPerson (talk) what the source says |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{for|the lunar impact crater|Andreas Vesalius (crater)}} |

|||

: ''This article covers irreducible complexity as used by those who argue for [[intelligent design]]. For information on irreducible complexity as used in [[Systems Theory]], see [[Irreducible complexity (Emergence)]].'' |

|||

{{Infobox Person |

|||

| name=Andreas Vesalius |

|||

| image = Vesalius Fabrica portrait.jpg |

|||

| image_size = 250px |

|||

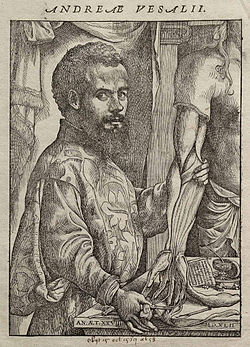

| caption = Portrait from the ''Fabrica'' |

|||

| birth_date = [[December 31]], [[1514]] |

|||

| birth_place = [[Brussels]], Belgium |

|||

| death_date = [[October 15]], [[1564]] |

|||

| death_place = [[Zakynthos]], Greece |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Andreas Vesalius''' ([[Brussels]], [[December 31]], [[1514]] - [[Zakynthos]], [[October 15]], [[1564]]) was an [[Anatomy|anatomist]], [[physician]], and author of one of the most influential books on [[human anatomy]], ''[[De humani corporis fabrica]]'' (''On the Workings of the Human Body''). Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy. |

|||

{{Intelligent Design}} |

|||

Vesalius is the latinized form of '''Andreas van Wesel'''. He is sometimes also referred to as '''Andreas Vesal'''. |

|||

'''Irreducible complexity''' (IC) is an [[argument]] made by proponents of [[intelligent design]] that certain [[biological systems]] are too complex to have [[evolution|evolved]] from simpler, or "less complete" predecessors, through [[natural selection]] acting upon a series of advantageous naturally occurring chance [[mutations]]. It is one of two main arguments intended to support intelligent design, the other being [[specified complexity]].<ref name=ForrestMayPaper>{{citation | url= http://www.centerforinquiry.net/uploads/attachments/intelligent-design.pdf| title = Understanding the Intelligent Design Creationist Movement: Its True Nature and Goals. A Position Paper from the Center for Inquiry, Office of Public Policy| first = Barbara| last = Forrest| author-link = Barbara Forrest | date = May,2007| month = May| year = 2007| publisher = Center for Inquiry, Inc.| place = Washington, D.C.|accessdate = 2007-08-22}}.</ref> It is dismissed by the [[scientific community]]<ref>"We therefore find that Professor Behe’s claim for irreducible complexity has been refuted in peer-reviewed research papers and has been rejected by the scientific community at large." [[s:Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District/4:Whether ID Is Science|Ruling, Judge John E. Jones III, Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District]]</ref> and intelligent design has been referred to as [[pseudoscience]].<ref>"True in this latest creationist variant, advocates of so-called intelligent design ... use more slick, pseudoscientific language. They talk about things like 'irreducible complexity'" — {{cite book | last = Shulman | first = Seth | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Undermining Science: Suppression and Distortion in the Bush Administration| publisher = University of California Press | date = January 8, 2007 | location = | pages = p 13 | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 0520247027}}"for most members of the mainstream scientific community, ID is not a scientific theory, but a creationist pseudoscience." [http://www.hcs.harvard.edu/~hsr/fall2005/mu.pdf Trojan Horse or Legitimate Science: Deconstructing the Debate over Intelligent Design] David Mu. Harvard Science Review, Volume 19, Issue 1, Fall 2005. [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1103713 Why Intelligent Design Isn't Intelligent Review of: Unintelligent Design, by Mark Perakh] Mark D. Decker. College of Biological Sciences, General Biology Program, University of Minnesota [http://www.texscience.org/files/faqs.htm Frequently Asked Questions About the Texas Science Textbook Adoption Controversy] "The Discovery Institute and ID proponents have a number of goals that they hope to achieve using disingenuous and mendacious methods of marketing, publicity, and political persuasion. They do not practice real science because that takes too long, but mainly because this method requires that one have actual evidence and logical reasons for one's conclusions, and the ID proponents just don't have those. If they had such resources, they would use them, and not the disreputable methods they actually use."</ref> |

|||

==Early life and education == |

|||

Biochemistry professor [[Michael Behe]], the originator of the argument of irreducible complexity, defines an irreducibly complex system as one "composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning".<ref>''Darwin's Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution'', Michael Behe, 1996, quoted in [http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/behe.html Irreducible Complexity and Michael Behe] (retrieved [[8 January]] [[2006]])</ref> These examples are said to demonstrate that modern biological forms could not have evolved naturally. Critics consider that most, or all, of the examples were based on misunderstandings of the workings of the biological systems in question, and consider the low quality of these examples excellent evidence for the [[argument from ignorance]]. |

|||

Vesalius was born in [[Brussels]], then in the [[Habsburg Netherlands]], to a family of physicians. His great-grandfather, Jan van Wesel, probably born in [[Wesel]], received his medical degree from the [[University of Pavia]] and taught medicine in 1428 at the then newly founded [[Catholic University of Leuven|University of Leuven]]. His grandfather, Everard van Wesel, was the Royal Physician of [[Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor|Emperor Maximilian]], while his father, Andries van Wesel, went on to serve as [[apothecary]] to Maximillian, and later a [[valet de chambre]] to his successor [[Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor|Charles V]]. Andries encouraged his son to continue in the family tradition, and enrolled him in the [[Brethren of the Common Life]] in Brussels to learn [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Latin]] according to standards of the era. |

|||

In the 2005 [[Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District]] trial, Behe gave testimony on the subject of irreducible complexity. The court found that "Professor Behe's claim for irreducible complexity has been refuted in peer-reviewed research papers and has been rejected by the scientific community at large."<ref name="dover_behe_ruling">[[s:Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District/4:Whether ID Is Science#4. Whether ID is Science|Ruling, Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, page 64]]</ref> |

|||

Nonetheless, irreducible complexity continues to be cited as an important argument by creationists, particularly intelligent design proponents. |

|||

In 1528 Vesalius entered the University of Louvain (''Pedagogium Castrensis'') taking arts, but when his father was appointed as the Valet de Chambre in 1532, he decided to pursue a career in medicine at the [[University of Paris]], where he moved in 1533. Here he studied the theories of [[Galen]] under the auspices of [[Jacques Dubois]] (Jacobus Sylvius) and [[Jean Fernel]]. It was during this time that he developed his interest in anatomy, and was often found examining bones at the [[Cimetière des Innocents|Cemetery of the Innocents]]. |

|||

== Definitions == |

|||

He was forced to leave Paris in 1536 due to the opening of hostilities between the Holy Roman Empire and France, and returned to [[Leuven]]. Here he completed his studies under [[Johannes Winter von Andernach]] and graduated the next year. His thesis, ''Paraphrasis in nonum librum Rhazae medici arabis clariss ad regem Almansorum de affectum singularum corporis partium curatione'', was a commentary on the ninth book of [[Rhazes]]. He remained at Leuven only briefly before leaving after a dispute with his professor. After settling briefly in [[Venice]] in 1536, he moved to the [[University of Padua]] (''Universitas aristarum'') to study for his doctorate, which he received in 1537. |

|||

The term "irreducible complexity" was originally defined by [[Behe]] as: |

|||

<blockquote>A single system which is composed of several interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, and where the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning. (''[[Darwin's Black Box]]'' p39 in the 2006 edition)</blockquote> |

|||

On graduation he was immediately offered the chair of Surgery and Anatomy (''explicator chirurgiae'') at Padua. He also guest lectured at [[University of Bologna|Bologna]] and [[University of Pisa|Pisa]]. Previously these topics had been taught primarily from reading classic texts, mainly [[Galen]], followed by an animal dissection by a barber-surgeon whose work was directed by the lecturer. No attempt was made to actually check Galen's claims; these were considered unassailable. Vesalius, on the other hand, carried out dissection as the primary teaching tool, handling the actual work himself while his students clustered around the table. Hands-on direct observation was considered the only reliable resource, a huge break with medieval practice. |

|||

Supporters of intelligent design use this term to refer to biological systems and organs that they [[belief|believe]] could not have come about by any series of small changes. They argue that anything less than the complete form of such a system or organ would not work ''at all'', or would in fact be a ''detriment'' to the organism, and would therefore never survive the process of natural selection. Although they accept that some complex systems and organs ''can'' be explained by evolution, they claim that organs and biological features which are ''irreducibly complex'' cannot be explained by current models, and that an intelligent designer must have created life or guided its evolution. Accordingly, the debate on irreducible complexity concerns two questions: whether irreducible complexity can be found in nature, and what significance it would have if it did exist in nature. |

|||

He kept meticulous drawings of his work for his students in the form of six large illustrated anatomical tables. When he found that some of these were being widely copied, he published them all in 1538 under the title ''Tabulae Anatomicae Sex''. He followed this in 1539 with an updated version of Galen's anatomical handbook, ''Institutiones Anatomicae''. When this reached Paris one of his former professors published an attack on this version. |

|||

A second definition given by Behe (his "evolutionary definition") is as follows: |

|||

<blockquote>An irreducibly complex evolutionary pathway is one that contains one or more unselected steps (that is, one or more necessary-but-unselected mutations). The degree of irreducible complexity is the number of unselected steps in the pathway.</blockquote> |

|||

In 1538 he also published a letter on [[venesection]], or [[bloodletting]]. This was a popular treatment for almost any illness, but there was some debate about where to take the blood from. The classical Greek procedure, advocated by Galen, was to let blood from a site near the location of the illness. However, the Muslim and medieval practice was to draw a smaller amount blood from a distant location. Vesalius' pamphlet supported Galen's view, and supported his arguments through anatomical diagrams. |

|||

Intelligent design advocate [[William Dembski]] gives this definition: |

|||

<blockquote>A system performing a given basic function is irreducibly complex if it includes a set of well-matched, mutually interacting, nonarbitrarily individuated parts such that each part in the set is indispensable to maintaining the system's basic, and therefore original, function. The set of these indispensable parts is known as the irreducible core of the system. (No Free Lunch, 285)</blockquote> |

|||

In 1539 a Paduan judge became interested in Vesalius' work, and made bodies of executed criminals available for dissection. He soon built up a wealth of detailed anatomical diagrams, the first accurate set to be produced. Many of these were produced by commissioned artists, and were therefore of much better quality than those produced previously. |

|||

==History== |

|||

===Forerunners=== |

|||

The argument from irreducible complexity is a descendant of the [[teleological argument]] for God (the argument from design or from complexity). This states that because certain things in nature are very complicated, they must have been designed. [[William Paley]] famously argued, in his 1802 [[watchmaker analogy]], that complexity in nature implies a God for the same reason that the existence of a watch implies the existence of a watchmaker.<ref name="paley" /> This argument has a long history, and can be traced back at least as far as [[Cicero]]'s ''De natura deorum'' ii.34.<ref>[http://oll.libertyfund.org/Texts/Cicero0070/NatureOfGods/HTMLs/0040_Pt03_Book2.html#hd_lf040.label.159 ''On the Nature of the Gods''], translated by Francis Brooks, London: Methuen, 1896.</ref><ref>See [[Henry Hallam]]'s ''Introduction to the Literature of Europe'' part iii chapter iii paragraph 26 footnote ''u''</ref> |

|||

In 1541, while in Bologna, Vesalius uncovered the fact that all of Galen's research had been based upon animal anatomy rather than the human; since dissection had been banned in ancient Rome, Galen had dissected [[Barbary Ape]]s instead, and argued that they would be anatomically similar to humans. As a result, he published a correction of Galen's ''Opera omnia'' and began writing his own anatomical text. Until Vesalius pointed this out, it had gone unnoticed and had long been the basis of studying human anatomy. However, some people still chose to follow Galen and resented Vesalius for calling attention to such glaring mistakes. |

|||

The idea that the interrelationship between parts of living things would have implications for their origins was raised by writers starting with [[Pierre Gassendi]] in the mid 17th century<ref>''De Generatione Animalium'', chapter III. Partial translation in: Howard B. Adelmann, ''Marcello Malpighi and the Evolution of Embryology'' Ithaca, New York, Cornell University Press, 1966, volume 2, pages 811-812.</ref> In the late 17th century, [[Thomas Burnet]] referred to "a multitude of pieces aptly joyn’d" to argue against the [[eternity]] of life.<ref>[http://www.sacred-texts.com/earth/ste/ste07.htm ''The Sacred Theory of the Earth''], 2nd edition, London: Walter Kettilby, 1691. Book I Chapter IV page 43</ref> In the early 18th century, [[Nicolas Malebranche]]<ref>''De la recherche de la verité'' 6.2.4, 6th edition, 1712. English translation ''The Search after Truth'', tr. and ed. Thomas M. Lennon and Paul J. Olscamp, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-521-58004-8. See page 465.</ref> used this idea to argue in favor of [[preformation]] (see [[homunculus]]), rather than full development (see [[epigenesis]]), of the individual embryo; and a similar argument about the origins of the individual was made by other 18th century students of natural history. Chapter XV of Paley's ''Natural Theology'' discusses at length what he called "relations" of parts of living things as an indication of their design.<ref name="paley"> [http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=A142&viewtype=text&pageseq=1 William Paley: ''Natural Theology; or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. Collected from the Appearances of Nature'' 12th edition, 1809] </ref> In a different application, in the early 19th century [[Georges Cuvier]] used the concept of "correlation of parts" in establishing the anatomy of animals from fragmentary remains.<ref>Andrew Pyle, Malebranche on Animal Generation: Preexistence and the Microscope, in Justin E.H. Smith, ed. (2006) ''The Problem of Animal Generation in Early Modern Philosophy'' ISBN 0-521-84077-5, pg 202-203</ref><ref>[http://talkreason.org/articles/chickegg.cfm The Chicken or the Egg]</ref> |

|||

Vesalius, undeterred, went on to stir up more controversy, this time disproving not just Galen but also [[Mondino de Liuzzi]] and even [[Aristotle]]; all three had made assumptions about the functions and structure of the heart that were clearly wrong. For instance, Vesalius noted that the heart had four chambers, the liver two lobes, and that the blood vessels originated in the heart, not the liver. Other famous examples of Vesalius disproving Galen in particular was his discovery that the lower jaw was only one bone, not two (which Galen had assumed from animal dissection) and his proof that blood did not pass through the [[interatrial septum]]. |

|||

While he did not originate the term, [[Charles Darwin]] identified the argument as a possible way to [[falsifiability|falsify]] a prediction of the theory of [[evolution]] at the outset. In ''[[The Origin of Species]]'', he wrote, "If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find out no such case."<ref>[[Charles Darwin|Darwin, Charles]] (1859). ''[[The Origin of Species|On the Origin of Species]]''. London: John Murray. |

|||

[http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F373&viewtype=side&pageseq=207 page 189, Chapter VI]</ref> Darwin's theory of evolution challenges the teleological argument by postulating an alternative explanation to that of an intelligent designer—namely, evolution by natural selection.{{Clarifyme|date=March 2008}}<!--What IS this trying to say, exactly? That Darwin set out specifically to challenge God?--> The argument from irreducible complexity attempts to demonstrate that certain biological features cannot be purely the product of Darwinian evolution. |

|||

In 1543, Vesalius conducted a public dissection of the body of [[Jakob Karrer von Gebweiler]], a notorious felon from the city of [[Basel]], [[Switzerland]]. With the cooperation of the surgeon [[Franz Jeckelmann]], he assembled the bones and finally donated the [[skeleton]] to the [[University of Basel]]. This preparation (“The Basel Skeleton”) is Vesalius’ only well-preserved skeletal preparation today, and is also the world’s oldest anatomical preparation. It is still displayed at the Anatomical Museum of the [[University of Basel]].<ref>http://www.vhsbb.ch/asp/pdf/senuni_07021213_zf_kurz.pdf</ref> |

|||

[[Hermann Joseph Muller|Hermann Muller]], in the early 20th century, discussed a concept similar to irreducible complexity. However, far from seeing this as a problem for evolution, he described the "interlocking" of biological features as a consequence to be expected of evolution, which would lead to irreversibility of some evolutionary changes.<ref>[http://www.genetics.org/cgi/reprint/3/5/422 Hermann J. Muller: Genetic variability, twin hybrids and constant hybrids, in a case of balanced lethal factors, ''Genetics'' 1918 3: 422-499], especially pages 463-464.</ref> He wrote, "Being thus finally woven, as it were, into the most intimate fabric of the organism, the once novel character can no longer be withdrawn with impunity, and may have become vitally necessary."<ref>Hermann J. Muller: Reversibility in evolution considered from the standpoint of genetics, ''Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society'', 4(3) 1939, 261-280, quotation from page 272.</ref> |

|||

==''De Corporis Fabrica''== |

|||

In 1974, [[Young Earth Creationist]] [[Henry M. Morris]] introduced a similar concept in his book "Scientific Creationism" in which he wrote; "This issue can actually be attacked quantitatively, using simple principles of mathematical probability. The problem is simply whether a complex system, in which many components function unitedly together, and in which each component is uniquely necessary to the efficient functioning of the whole, could ever arise by random processes."<ref>''Scientific Creationism'', edited by [[Henry M. Morris]], Master Books; General ed., 2nd ed edition (October 1974), ISBN-10: 0890510032 , page 59.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Vesalius Fabrica p190.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Vesalius's ''Fabrica'' contained many intricately detailed drawings of human dissections, often in allegorical poses.]] |

|||

In 1543, Vesalius asked [[Johannes Oporinus]] to help publish the seven-volume ''[[De humani corporis fabrica]]'' (''On the fabric of the human body''), a groundbreaking work of [[human anatomy]] he dedicated to Charles V and which most believe was illustrated by [[Titian]]'s pupil [[Jan Van Calcar|Jan Stephen van Calcar]]. A few weeks later he published an abridged edition for students, ''Andrea Vesalii suorum de humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome'', and dedicated it to [[Philip II of Spain]], son of the Emperor. |

|||

The work emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body — seeing human internal functioning as an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. This was in stark contrast to many of the anatomical models used previously, which had strong Galenic/Aristotelean elements, as well as elements of [[astrology]]. Although modern anatomical texts had been published by [[Mondino de Liuzzi|Mondino]] and [[Jacopo Berengario da Carpi|Berenger]], much of their work was clouded by their reverence for Galen and Arabian doctrines. |

|||

In 1981, Ariel Roth, in defense of the creation science position in the trial [[McLean v. Arkansas]], said of "complex integrated structures" that "This system would not be functional until all the parts were there ... How did these parts survive during evolution ...?"<ref>Normal L. Geisler, A. F. Brooke II, Mark J. Keough, ''The Creator in the Courtroom: "Scopes II"'', Milford, MI: Mott Media, 1982. ISBN 978-0-88062-020-8, p. 146 [http://www.antievolution.org/projects/mclean/new_site/docs/geislerbook.htm#Chapter%20Seven]</ref> |

|||

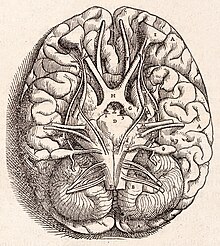

Besides the first good description of the [[sphenoid bone]], he showed that the [[sternum]] consists of three portions and the [[sacrum]] of five or six; and described accurately the [[vestibule of the ear|vestibule]] in the interior of the temporal bone. He not only verified the observation of Etienne on the valves of the hepatic veins, but he described the [[vena azygos]], and discovered the canal which passes in the fetus between the umbilical vein and the vena cava, since named [[ductus venosus]]. He described the [[omentum]], and its connections with the stomach, the [[spleen]] and the [[Colon (anatomy)|colon]]; gave the first correct views of the structure of the [[pylorus]]; observed the small size of the caecal appendix in man; gave the first good account of the [[mediastinum]] and [[pleura]] and the fullest description of the anatomy of the brain yet advanced. He did not understand the inferior recesses; and his account of the nerves is confused by regarding the optic as the first pair, the third as the fifth and the fifth as the seventh. |

|||

In 1985 [[Graham Cairns-Smith|Cairns-Smith]] wrote of "interlocking", "How can a complex collaboration between components evolve in small steps?" and used the analogy of the scaffolding in building an arch: "Surely there was 'scaffolding'. Before the multitudinous components of present biochemistry could come to lean together ''they had to lean on something else.''"<ref>Pages 39, 58-64, A. G. Cairns-Smith, ''Seven Clues to the Origin of Life: A Scientific Detective Story'', Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-521-27522-9</ref> |

|||

In this work, Vesalius also becomes the first person to describe [[mechanical ventilation]].<ref name="Resuscitation">Vallejo-Manzur F et al. (2003) "The resuscitation greats. Andreas Vesalius, the concept of an artificial airway." ''Resuscitation" 56:3-7</ref> |

|||

An essay in support of [[creationism]] published in 1994 referred to bacterial flagella as showing "multiple, integrated components", where "nothing about them works unless every one of their complexly fashioned and integrated components are in place" and asked the reader to "imagine the effects of natural selection on those organisms that fortuitously evolved the flagella ... without the concommitant [''sic''] control mechanisms".<ref>Richard D. Lumsden,''Not So Blind A Watchmaker'', Creation Research Society Quarterly, vol. 31 no. 1 (June, 1994), pages 13-22. Quotations from pages 13 and 20.</ref><ref>Eugenie C. Scott and Nicholas J. Matzke, Biological design in science classrooms, ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences'', vol. 104 suppl. 1 ([[May 15]], [[2007]]), pp. 8669-8676. See page 8672.</ref> |

|||

Though Vesalius' work was not the first such work based on actual autopsy, nor even the first work of this era, the production values, highly-detailed and intricate plates, and the fact that the artists who produced it were clearly present at the dissections themselves made it into an instant classic. Pirated editions were available almost immediately, a fact Vesalius acknowledged would happen in a printer's note. Vesalius was only 30 years old when the first edition of ''Fabrica'' was published. |

|||

An early concept of irreducibly complex systems comes from [[Ludwig von Bertalanffy]], a 20th-century Austrian biologist.<ref>Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1952). ''Problems of Life: An Evaluation of Modern Biological and Scientific Thought, pg 148'' ISBN 1-131-79242-4</ref> He believed that complex systems must be examined as complete, [[irreducible (philosophy)|irreducible]] systems in order to fully understand how they work. He extended his work on biological complexity into a general theory of systems in a book titled ''[[Systems theory|General Systems Theory]]''. |

|||

===Quote=== |

|||

After [[James D. Watson|James Watson]] and [[Francis Crick]] published the structure of [[DNA]] in the early 1950s, General Systems Theory lost many of its adherents in the physical and biological sciences.<ref>''Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology'', Jacques Monod, 1971</ref> However, Systems theory remained popular in the social sciences long after its demise in the physical and biological sciences. |

|||

*"When I undertake the dissection of a human cadaver I pass a stout rope tied like a noose beneath the lower jaw and through the zygomas up to the top of the head... The lower end of the noose I run through a pulley fixed to a beam in the room so that I may raise or lower the cadaver as it hangs there or turn around in any direction to suit my purpose; ... You must take care not to put the noose around the neck, unless some of the muscles connected to the occipital bone have already been cut away. ..."<ref> |

|||

Andreas Vesalius, ''[[De humani corporis fabrica]]'' (1543) Book II Ch. 24, 268. Trans. William Frank Richardson, ''On the Fabric of the Human Body'' (1999) Book II, 234. As quoted by W.F. Bynum & Roy Porter (2005), ''Oxford Dictionary of Scientific Quotations'' ''Andreas Vesalius'', '''595''':'''2''' ISBN 0-19-858409-1 |

|||

</ref> --Andreas Vesalius, '''595''':'''2''' of Bynum & Porter, ''Oxford Dictionary of Scientific Quotations'' 2005 |

|||

==Imperial physician and death== |

|||

===Origins=== |

|||

[[Image:1543,AndreasVesalius'Fabrica,BaseOfTheBrain.jpg|thumb|Base of the [[Brain]], showing [[optic chiasm]]a, [[cerebellum]], [[olfactory bulb]]s, etc.]] |

|||

[[Image:Darwinsblackbox.jpg|thumb|left|160px|[[Michael Behe]]'s controversial book ''[[Darwin's Black Box]]'' popularized the concept of irreducible complexity.]] |

|||

Soon after publication, Vesalius was invited as Imperial physician to the court of [[Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor|Emperor Charles V]]. He informed the Venetian Senate that he was leaving his post in Padua, which prompted [[Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany|Duke Cosimo I de' Medici]] to invite him to move to the expanding university in Pisa, which he turned down. Vesalius took up a position in the court, where he had to deal with the other physicians mocking him as being a barber. |

|||

[[Michael Behe]] developed his ideas on the concept around 1992, in the early days of the '[[wedge strategy|wedge movement]]', and first presented his ideas about "irreducible complexity" in June 1993 when the "Johnson-Behe cadre of scholars" met at Pajaro Dunes in California.<ref name=bfwedge>[[Barbara Forrest]], [http://www.talkreason.org/articles/Wedge.cfm#I The Wedge at Work]. Talk Reason, Chapter 1 of the book "Intelligent Design Creationism and Its Critics" (MIT Press, 2001), Retrieved [[2007-05-28]].</ref> He set out his ideas in the second edition of ''[[Of Pandas and People]]'' published in 1993, extensively revising Chapter 6 ''Biochemical Similarities'' with new sections on the complex mechanism of blood clotting and on the origin of proteins.<ref>[http://www.ncseweb.org/resources/articles/6343_60_sonleitner_the_new_ipa_11_24_2004.asp The New Pandas: Has Creationist Scholarship Improved?] Comments on 1993 Revisions by Frank J. Sonleitner (1994)<br>[http://www.ncseweb.org/resources/articles/8442_1_introduction_iof_pandas__11_23_2004.asp Introduction: Of Pandas and People, the foundational work of the 'Intelligent Design' movement] by Nick Matzke 2004,<br>[http://www.ncseweb.org/resources/rncse_content/vol24/4838_design_on_trial_in_dover_penn_12_30_1899.asp Design on Trial in Dover, Pennsylvania] by Nicholas J Matzke, NCSE Public Information Project Specialist</ref> |

|||

Over the next twelve years Vesalius travelled with the court, treating injuries from battle or tournaments, performing surgeries and postmortems, and writing private letters addressing specific medical questions. During these years he also wrote ''Radicis Chynae'', a short text on the properties of a medical plant, whose use he defended, as well as defense for his anatomical findings. This elicited a new round of attacks on his work that called for him to be punished by the emperor. In 1551, Charles V commissioned an inquiry in [[Salamanca]] to investigate the religious implications of his methods. Vesalius' work was cleared by the board, but the attacks continued. Four years later one of his main detractors published an article that claimed that the human body itself had changed since Galen had studied it. |

|||

He first used the term "irreducible complexity" in his 1996 book ''[[Darwin's Black Box]]'', to refer to certain complex biochemical [[cell (biology)|cellular]] systems. He posits that evolutionary mechanisms cannot explain the development of such "irreducibly complex" systems. Notably, Behe credits philosopher [[William Paley]] for the original concept, not von Bertalanffy, and suggests that his application of the concept to biological systems is entirely original. |

|||

Intelligent design advocates argue that irreducibly complex systems must have been deliberately engineered by some form of [[intelligent designer|intelligence]]. |

|||

After the abdication of Charles he continued at court in great favour with his son Philip II, who rewarded him with a pension for life and by being made a count palatine. In 1555 he published a revised edition of ''De Corporis''. |

|||

In 2001, [[Michael Behe]] wrote: "[T]here is an asymmetry between my current definition of irreducible complexity and the task facing natural selection. I hope to repair this defect in future work." Behe specifically explained that the "current definition puts the focus on removing a part from an already functioning system", but the "difficult task facing Darwinian evolution, however, would not be to remove parts from sophisticated pre-existing systems; it would be to bring together components to make a new system in the first place". In the 2005 [[Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District|Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District trial]], Behe testified under oath that he "did not judge [the asymmetry] serious enough to [have revised the book] yet."<ref>Behe, Michael (2001). [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/klu/biph/2001/00000016/00000005/00353967 Reply to My Critics]. See also [http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/dover/day12am2.html Behe's testimonial in Kitzmiller v. Dover]</ref> |

|||

In 1564 Vesalius went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He sailed with the Venetian fleet under [[James Malatesta]] via [[Cyprus]]. When he reached [[Jerusalem]], he received a message from the Venetian senate requesting him again to accept the Paduan professorship, which had become vacant by the death of his friend and pupil [[Gabriele Falloppio|Fallopius]]. |

|||

Behe additionally testified that the presence of irreducible complexity in organisms would not rule out the involvement of evolutionary mechanisms in the development of organic life. He further testified that he knew of no earlier "peer reviewed articles in scientific journals discussing the intelligent design of the blood clotting cascade," but that there were "probably a large number of peer reviewed articles in science journals that demonstrate that the blood clotting system is indeed a purposeful arrangement of parts of great complexity and sophistication."<ref>Behe, Michael 2005 [[Wikisource:Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District/4:Whether ID Is Science#Page 88 of 139|Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District 4: whether ID is science (p. 88)]]</ref> (The result of the trial was the ruling that "intelligent design is not science and is essentially religious in nature".)<ref>[[s:Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District/6:Curriculum, Conclusion#H. Conclusion|Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District 6: Conclusion, section H]]</ref> |

|||

After struggling for many days with the adverse winds in the [[Ionian Sea]], he was wrecked on the island of [[Zakynthos]]. Here he soon died in such debt that, if a benefactor had not paid for a funeral, his remains would have been thrown to the animals. At the time of his death he was scarcely fifty years of age. |

|||

According to the theory of evolution, genetic variations occur without specific design or intent. The environment "selects" the variants that have the highest fitness, which are then passed on to the next generation of organisms. Change occurs by the gradual operation of natural forces over time, perhaps slowly, perhaps more quickly (see [[punctuated equilibrium]]). This process is able to [[adaptation|adapt]] complex structures from simpler beginnings, or convert complex structures from one function to another (see [[spandrel (biology)|spandrel]]). Most intelligent design advocates accept that evolution occurs through mutation and natural selection at the "[[microevolution|micro level]]", such as changing the relative frequency of various beak lengths in finches, but assert that it cannot account for irreducible complexity, because none of the parts of an irreducible system would be functional or advantageous until the entire system is in place. |

|||

For many years it was assumed that Vesalius's pilgrimage was due to pressures of the [[Inquisition]]. Today this is generally considered to be without foundation (see C.D. O'Malley ''Andreas Vesalius' Pilgrimage'', Isis 45:2, 1954) and is dismissed by modern biographers. It appears the story was spread by [[Hubert Languet]], who served as de Saxe under Charles V and then the prince of Orange. He claimed in 1565 that Vesalius was performing an autopsy on an aristocrat in Spain when it was found that the heart was still beating, leading to the Inquisition condemning him to death. The story went on to claim that Philip II had the sentence transformed into a pilgrimage. The story re-surfaced several times over the next few years, living on until recent times. |

|||

Behe uses the mousetrap as an illustrative example of this concept. A mousetrap consists of several interacting pieces—the base, the catch, the spring, the hammer. Behe contends that all of these must be in place for the mousetrap to work, and that the removal of any one piece destroys the function of the mousetrap. Likewise, biological systems require multiple parts working together in order to function. Intelligent design advocates claim that natural selection could not create from scratch those systems for which science is currently unable to find a viable evolutionary pathway of successive, slight modifications, because the selectable function is only present when all parts are assembled. Behe's original examples of irreducibly complex mechanisms included the bacterial [[flagellum]] of ''[[E. coli]]'', the [[blood clotting]] cascade, [[cilia]], and the adaptive [[immune system]]. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

[[Image:Mausefalle 300px.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Michael Behe]] believes that many aspects of life show evidence of design, using the [[mousetrap]] in an analogy disputed by others.<ref name=trap>[http://udel.edu/~mcdonald/mousetrap.html A reducibly complex mousetrap] (graphics-intensive, requires [[JavaScript]])</ref>]] |

|||

* [[Timeline of medicine and medical technology]] |

|||

* [[InVesalius]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

Behe argues that organs and biological features which are irreducibly complex cannot be wholly explained by current models of [[evolution]]. He argues that: |

|||

*[http://www.bronwenwilson.ca/physiognomy/pages/biographies.html Vesalius], by Alison Kassab |

|||

<blockquote>An irreducibly complex system cannot be produced directly (that is, by continuously improving the initial function, which continues to work by the same mechanism) by slight, successive modifications of a precursor system, because any precursor to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a part is by definition nonfunctional.</blockquote> |

|||

<references/> |

|||

Irreducible complexity is not an argument that evolution does not occur, but rather an argument that it is "incomplete". In the last chapter of ''[[Darwin's Black Box]]'', Behe goes on to explain his view that irreducible complexity is evidence for [[intelligent design]]. Mainstream critics, however, argue that irreducible complexity, as defined by Behe, can be generated by known evolutionary mechanisms. Behe's claim that no scientific literature adequately modeled the origins of biochemical systems through evolutionary mechanisms has been challenged by[[TalkOrigins Archive|TalkOrigins]].<ref>[http://www.talkorigins.org/indexcc/CA/CA350.html Claim CA350: Professional literature is silent on the subject of the evolution of biochemical systems] TalkOrigins Archive.</ref><ref> {{cite book | last = Behe | first = Michael J. | authorlink = Michael Behe | title = Darwin's black box: the biochemical challenge to evolution | origdate = 1996 | isbn = 0684827549 | pages = 72 | chapter = | quote = "Yet here again the evolutionary literature is totally missing. No scientist has ever published a model to account for the gradual evolution of this extraordinary molecular machine" }}</ref> The judge in the Dover trial wrote "By defining irreducible complexity in the way that he has, Professor Behe attempts to exclude the phenomenon of [[exaptation]] by definitional fiat, ignoring as he does so abundant evidence which refutes his argument. Notably, the [[United States National Academy of Sciences|NAS]] has rejected Professor Behe’s claim for irreducible complexity..."<ref>[[s:Kitzmiller_v._Dover_Area_School_District/4:Whether_ID_Is_Science#Page_74_of_139|Ruling,]] [[Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District]], December 2005. Page 74.</ref> |

|||

== Stated examples == |

|||

Behe and others have suggested a number of biological features that they believe may be irreducibly complex. |

|||

=== Blood clotting cascade === |

|||

The blood clotting or [[coagulation]] cascade in vertebrates is a complex biological pathway which that is given as an example of apparent irreducible complexity.<ref>Action, George [http://www.talkorigins.org/origins/postmonth/feb97.html "Behe and the Blood Clotting Cascade"]</ref> |

|||

The irreducible complexity argument assumes that the necessary parts of a system have always been necessary, and therefore could not have been added sequentially. However, in evolution, something which is at first merely advantageous can later become necessary. For example, one of the clotting factors that Behe listed as a part of the clotting cascade was later found to be absent in whales, demonstrating that it is not essential for a clotting system.<ref>{{cite journal | author=Semba U, Shibuya Y, Okabe H, Yamamoto T | title=Whale Hageman factor (factor XII): prevented production due to pseudogene conversion | journal=Thromb Res | year=1998 | pages=31–7 | volume=90 | issue=1 | pmid=9678675 | doi = 10.1016/S0049-3848(97)00307-1 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> Many purportedly irreducible structures can be found in other organisms as much simpler systems that utilize fewer parts. These systems, in turn, may have had even simpler precursors that are now extinct. The "improbability argument" also misrepresents natural selection. It is correct to say that a set of simultaneous mutations that form a complex protein structure is so unlikely as to be unfeasible, but that is not what Darwin advocated. His explanation is based on small accumulated changes that take place without a final goal. Each step must be advantageous in its own right, although biologists may not yet understand the reason behind all of them—for example, jawless fish accomplish blood clotting with just six proteins instead of the full 10.<ref>[http://www.newscientisttech.com/article/mg18725073.800;jsessionid=MJJHNOPOKALE Creationism special: A sceptic's guide to intelligent design], New Scientist, [[9 July]] [[2005]]</ref> |

|||

=== Eye === |

|||

{{main|Evolution of the eye}} |

|||

[[Image:Stages in the evolution of the eye.png|thumb|300px|Often used as an example of irreducible complexity.<br/>(a) A pigment spot<br/>(b) A simple pigment cup<br/>(c) The simple optic cup found in [[abalone]]<br/>(d) The complex lensed eye of the marine snail and the octopus]] |

|||

The [[eye]] is a famous example of a supposedly irreducibly complex structure, due to its many elaborate and interlocking parts, seemingly all dependent upon one another. It is frequently cited by intelligent design and creationism advocates as an example of irreducible complexity. Behe used the "development of the eye problem" as evidence for intelligent design in ''Darwin's Black Box''. Although Behe acknowledged that the evolution of the larger anatomical features of the eye have been well-explained, he claimed that the complexity of the minute biochemical reactions required at a molecular level for light sensitivity still defies explanation. Creationist [[Jonathan Sarfati]] has described the eye as evolutionary biologists' "greatest challenge as an example of superb 'irreducible complexity' in God's creation", specifically pointing to the supposed "vast complexity" required for transparency.<ref name="aig">[[Jonathan Sarfati|Sarfati, Jonathan]] (2000). [http://www.answersingenesis.org/home/area/re2/chapter10.asp Argument: 'Irreducible complexity'], from ''[[Refuting Evolution]]'' ([[Answers in Genesis]]).</ref> |

|||

In an often mis-quoted<ref>[http://www.talkorigins.org/indexcc/CA/CA113_1.html CA113.1: Evolution of the eye<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> passage from ''[[The Origin of Species]]'', [[Charles Darwin]] appears to acknowledge the eye's development as a difficulty for his theory. However, the quote in context shows that Darwin actually had a very good understanding of the evolution of the eye. He notes that "to suppose that the eye [...] could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible degree". Yet this observation was merely a rhetorical device for Darwin. He goes on to explain that if gradual evolution of the eye could be shown to be possible, "the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection [...] can hardly be considered real". He then proceeded to roughly map out a likely course for evolution using examples of gradually more complex eyes of various species. <ref>[[Charles Darwin|Darwin, Charles]] (1859). ''[[The Origin of Species|On the Origin of Species]]''. London: John Murray. |

|||

[http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F373&viewtype=side&pageseq=204 pages 186ff, Chapter VI]</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Evolution eye.png|thumb|left|200px|The eyes of vertebrates (left) and invertebrates such as the [[octopus]] (right) developed independently: vertebrates evolved an inverted [[retina]] with a [[Blind spot (vision)|blind spot]] over their [[optic disc]], whereas octopuses avoided this with a non-inverted retina.]] |

|||

Since Darwin's day, the [[evolution of the eye|eye's ancestry]] has become much better understood. Although learning about the construction of ancient eyes through fossil evidence is problematic due to the soft tissues leaving no imprint or remains, genetic and comparative anatomical evidence has increasingly supported the idea of a common ancestry for all eyes.<ref>Halder, G., Callaerts, P. and Gehring, W.J. (1995). "New perspectives on eye evolution." ''Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.'' 5 (pp. 602 –609).</ref><ref>Halder, G., Callaerts, P. and Gehring, W.J. (1995). "Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the ''eyeless'' gene in ''Drosophila''". ''Science'' 267 (pp. 1788–1792).</ref><ref>Tomarev, S.I., Callaerts, P., Kos, L., Zinovieva, R., Halder, G., Gehring, W., and Piatigorsky, J. (1997). "Squid ''Pax-6'' and eye development." Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 94 (pp. 2421–2426).</ref> |

|||

As Behe admits, current evidence does suggest possible evolutionary lineages for the origins of the anatomical features of the eye, for example, that eyes originated as simple patches of [[photoreceptor]] cells that could detect the presence or absence of light, but not its direction. By developing a small depression for the photosensitive cells, the organisms obtained a better sense of the light's source, and by continuing to deepen the depression into a pit so that light would strike certain cells depending on its angle, increasingly precise visible information was possible. The aperture of the eye was then shrunk so that light is focused, turning the eye into a [[pinhole camera]] and allowing the organism to dimly make out shapes—the [[nautilus]] is a modern example of an animal with such an eye. Finally, the protective layer of transparent cells over the aperture was differentiated into a crude [[lens (anatomy)|lens]], and the interior of the eye was filled with humours to assist in focusing images.<ref>Fernald, Russell D. (2001). [http://www.karger.com/gazette/64/fernald/art_1_1.htm The Evolution of Eyes: Why Do We See What We See?] ''Karger Gazette'' 64: "The Eye in Focus".</ref><ref>Fernald, Russell D. (1998). ''Aquatic Adaptations in Fish Eyes''. New York, Springer.</ref><ref>Fernald, Russell D. (1997). [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9310200&dopt=Abstract" The evolution of eyes."] ''Brain Behav Evol.'' 50 (pp. 253–259).</ref> In this way, eyes are recognized by modern biologists as actually a relatively unambiguous and simple structure to evolve, and many of the major developments of the eye's evolution are believed to have taken place over only a few million years, during the [[Cambrian explosion]].<ref>Conway-Morris, S. (1998). ''The Crucible of Creation''. Oxford: Oxford University Press.</ref> However, according to Behe, the complexity of light sensitivity at the molecular level and the minute biochemical reactions required for those first "simple patches of photoreceptor[s]" still defies explanation. |

|||

=== Flagella === |

|||

{{main|Evolution of flagella}} |

|||

The [[flagella]] of certain bacteria constitute a [[molecular motor]] requiring the interaction of about 40 complex protein parts, and the absence of any one of these proteins causes the flagella to fail to function. Behe holds that the flagellum "engine" is irreducibly complex because if we try to reduce its complexity by positing an earlier and simpler stage of its evolutionary development, we get an organism which functions improperly. |

|||

Mainstream scientists regard this argument as having been largely disproved in the light of fairly recent research.<ref>Miller, Kenneth R. [http://www.millerandlevine.com/km/evol/design2/article.html The Flagellum Unspun: The Collapse of "Irreducible Complexity"] with reply [http://www.designinference.com/documents/2003.02.Miller_Response.htm here]</ref> They point out that the basal body of the flagella has been found to be similar to the [[Type III secretory system]] (TTSS), a needle-like structure that pathogenic germs such as ''[[Salmonella]]'' and ''[[Yersinia pestis]]'' use to inject [[toxin]]s into living [[eucaryote]] cells. The needle's base has ten elements in common with the flagellum, but it is missing forty of the proteins that make a flagellum work.<ref>[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQQ7ubVIqo4 Kenneth Miller's The Collapse of Intelligent Design: Section 5 Bacterial Flagellum] (Case Western Reserve University, 2006 [[January 3]])</ref> Thus, this system seems to negate the claim that taking away any of the flagellum's parts would render it useless. This has caused [[Kenneth R. Miller|Kenneth Miller]] to note that, "The parts of this supposedly irreducibly complex system actually have functions of their own."<ref>[http://debatebothsides.com/showthread.php?t=38338 Unlocking cell secrets bolsters evolutionists] (Chicago Tribune, 2006 [[February 13]])</ref><ref>[http://www.talkdesign.org/faqs/flagellum.html Evolution in (Brownian) space: a model for the origin of the bacterial flagellum] (Talk Design, 2006 [[September]])</ref> |

|||

== Response of the scientific community == |

|||

Like intelligent design, the concept it seeks to support, irreducible complexity has failed to gain any notable acceptance within the [[scientific community]]. One science writer called it a "full-blown intellectual surrender strategy."<ref>Mirsky, Steve [http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=00022DE1-0C15-11E6-B75283414B7F0000 Sticker Shock: In the beginning was the cautionary advisory] ''Scientific American'', February 2005</ref> |

|||

===Reducibility of "irreducible" systems=== |

|||

Potentially viable evolutionary pathways have been proposed for allegedly irreducibly complex systems such as blood clotting, the immune system<ref>Matt Inlay, 2002. "[http://www.talkdesign.org/faqs/Evolving_Immunity.html Evolving Immunity]." In ''TalkDesign.org''.</ref> and the flagellum,<ref>Nicholas J. Matzke, 2003. "[http://www.talkdesign.org/faqs/flagellum_background.html Evolution in (Brownian) space: a model for the origin of the bacterial flagellum]."</ref><ref>Mark Pallen and Nicholas J. Matzke, 2006, "[http://www.pandasthumb.org/archives/2006/09/flagellum_evolu.html From ''The Origin of Species'' to the origin of bacterial flagella]." ''Nature Reviews Microbiology'', 4(10), 784-790.</ref> which were the three examples Behe used. Even his example of a mousetrap was shown to be reducible by John H. McDonald.<ref name="trap" /> If irreducible complexity is an insurmountable obstacle to evolution, it should not be possible to conceive of such pathways—Behe has remarked that such plausible pathways would defeat his argument. |

|||

Niall Shanks and Karl H. Joplin, both of [[East Tennessee State University]], have shown that systems satisfying Behe's characterization of irreducible biochemical complexity can arise naturally and spontaneously as the result of self-organizing chemical processes.<ref>Shanks, Niall [http://www.asa3.org/ASA/topics/Apologetics/POS6-99ShenksJoplin.html Redundant Complexity:A Critical Analysis of Intelligent Design in Biochemistry]</ref><ref>Niall Shanks and Karl H. Joplin. [http://www.asa3.org/ASA/topics/Apologetics/POS6-99ShenksJoplin.html Redundant Complexity:A Critical Analysis of Intelligent Design in Biochemistry.] East Tennessee State University.</ref> They also assert that what evolved biochemical and molecular systems actually exhibit is "redundant complexity"—a kind of complexity that is the product of an evolved biochemical process. They claim that Behe overestimated the significance of irreducible complexity because of his simple, linear view of biochemical reactions, resulting in his taking snapshots of selective features of biological systems, structures and processes, while ignoring the redundant complexity of the context in which those features are naturally embedded. They also criticized his over-reliance of overly simplistic metaphors, such as his mousetrap. In addition, research published in the peer-reviewed journal [[Nature (journal)|Nature]] has shown that computer simulations of evolution demonstrate that it is possible for irreducible complexity to evolve naturally.<ref>{{cite journal | author=[[Richard Lenski|Lenski RE]], Ofria C, Pennock RT, Adami C | title=The evolutionary origin of complex features | journal=Nature | year=2003 | pages=139–44 | volume=423 | issue=6936 | pmid=12736677 | doi=10.1038/nature01568}}</ref> |

|||

It is illustrative to compare a mousetrap with a cat, in this context. Both normally function so as to control the mouse population. The cat has many parts that can be removed leaving it still functional; for example, its tail can be bobbed, or it can lose an ear in a fight. Comparing the cat and the mousetrap, then, one sees that the mousetrap (which is not alive) offers better evidence, in terms of irreducible complexity, for intelligent design than the cat. Even looking at the mousetrap analogy, several critics have described ways in which the parts of the mousetrap could have independent uses or could develop in stages, demonstrating that it is not irreducibly complex.<ref name=trap/> |

|||

Moreover, even cases where removing a certain component in an organic system will cause the system to fail do not demonstrate that the system couldn't have been formed in a step-by-step, evolutionary process. By analogy, stone arches are irreducibly complex—if you remove any stone the arch will collapse—yet we build them easily enough, one stone at a time, by building over scaffolding that is removed afterward. Similarly, [[natural arch|naturally occurring arches]] of stone are formed by weathering away bits of stone from a large concretion that has formed previously. |

|||

Evolution can act to simplify as well as to complicate. This raises the possibility that seemingly irreducibly complex biological features may have been achieved with a period of increasing complexity, followed by a period of simplification. |

|||

In April 2006 a team led by Joe Thornton, assistant professor of biology at the University of Oregon's Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, using techniques for resurrecting ancient genes, scientists for the first time reconstructed the evolution of an apparently irreducibly complex molecular system. The research was published in the [[April 7]] issue of ''Science''.<ref>[http://www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/filesDB-download.php?command=download&id=746 Press release] University of Oregon, [[April 4]], [[2006]].</ref> |

|||

It may be that irreducible complexity does not actually exist in nature, and that the examples given by Behe and others are not in fact irreducibly complex, but can be explained in terms of simpler precursors. There has also been a theory that challenges irreducible complexity called [[facilitated variation]]. The theory has been presented in 2005 by [[Marc W. Kirschner]], a professor and chair of Department of Systems Biology at [[Harvard Medical School]], and [[John C. Gerhart]], a professor in Molecular and Cell Biology, [[University of California, Berkeley]]. In their theory, they describe how certain mutation and changes can cause apparent irreducible complexity. Thus, seemingly irreducibly complex structures are merely "very complex", or they are simply misunderstood or misrepresented. |

|||

===Gradual adaptation to new functions=== |

|||

{{main|Exaptation}} |

|||

The precursors of complex systems, when they are not useful in themselves, may be useful to perform other, unrelated functions. Evolutionary biologists argue that evolution often works in this kind of blind, haphazard manner in which the function of an early form is not necessarily the same as the function of the later form. The term used for this process is "exaptation". The [[Evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles|mammalian middle ear]] (derived from a jawbone) and the [[Giant Panda|panda]]'s thumb (derived from a wrist bone spur) are considered classic examples. A 2006 article in ''Nature'' demonstrates intermediate states leading toward the development of the ear in a [[Devonian]] fish (about 360 million years ago).<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Nature|volume=439|pages=318–321|date=January 19, 2006|author=M. Brazeau and P. Ahlberg|doi=10.1038/nature04196|issue=7074|title=Tetrapod-like middle ear architecture in a Devonian fish}}</ref> Furthermore, recent research shows that viruses play a heretofore unexpectedly great role in evolution by mixing and matching genes from various hosts. |

|||

Arguments for irreducibility often assume that things started out the same way they ended up—as we see them now. However, that may not necessarily be the case. |

|||

=== Falsifiability and experimental evidence === |

|||

Some critics, such as [[Jerry Coyne]] (professor of [[evolutionary biology]] at the [[University of Chicago]]) and [[Eugenie Scott]] (a [[physical anthropology|physical anthropologist]] and executive director of the [[National Center for Science Education]]) have argued that the concept of irreducible complexity, and more generally, the theory of [[intelligent design]] is not [[falsifiable]], and therefore, not [[scientific]]. |

|||

Behe argues that the theory that irreducibly complex systems could not have been evolved can be falsified by an experiment where such systems are evolved. For example, he posits taking bacteria with no [[flagella|flagellum]] and imposing a selective pressure for mobility. If, after a few thousand generations, the bacteria evolved the bacterial flagellum, then Behe believes that this would refute his theory. |

|||

Other critics take a different approach, pointing to experimental evidence that they believe falsifies the argument for Intelligent Design from irreducible complexity. For example, [[Kenneth R. Miller|Kenneth Miller]] cites the lab work of [http://homepage.mac.com/barryghall/BarryHall.html Barry G. Hall] on [[E. coli]], which he asserts is evidence that "Behe is wrong."<ref><cite>Finding Darwin's God</cite> Kenneth Miller. Harper Collins, 1999</ref> |

|||

Other evidence that irreducible complexity is not a problem for evolution comes from the field of [[computer science]], where computer analogues of the processes of evolution are routinely used to automatically design complex solutions to problems. The results of such [[Genetic Algorithms]] are frequently irreducibly complex since the process, like evolution, both removes non-essential components over time as well as adding new components. The removal of unused components with no essential function, like the natural process where rock underneath a [[natural arch]] is removed, can produce irreducibly complex structures without requiring the intervention of a designer. Researchers applying these algorithms are automatically producing human competitive designs--but no human designer is required.<ref>[http://www.genetic-programming.com/humancompetitive.html 36 Human-Competitive Results Produced by Genetic Programming]</ref> |

|||

===Argument from ignorance=== |

|||

Intelligent design proponents attribute to an intelligent designer those biological structures they believe are irreducibly complex and where a natural explanation is absent or insufficient to account for them.<ref>Michael Behe. Evidence for Intelligent Design from Biochemistry. 1996.[http://www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command=view&id=51]</ref> However, critics view irreducible complexity as a special case of the "complexity indicates design" claim, and thus see it as an [[argument from ignorance]] and [[God of the gaps]] argument.<ref>Index to Creationist Claims. Mark Isaak. The Talk.Origins Archive. "Irreducible complexity and complex specified information are special cases of the "complexity indicates design" claim; they are also arguments from incredulity." [http://www.talkorigins.org/indexcc/CI/CI101.html] "The argument from incredulity creates a god of the gaps." [http://www.talkorigins.org/indexcc/CA/CA100.html]</ref> |

|||

[[Eugenie Scott]], along with [[Glenn Branch]] and other critics, has argued that many points raised by intelligent design proponents are arguments from ignorance.<ref>Eugenie C. Scott and Glenn Branch, [http://www.ncseweb.org/resources/articles/996_intelligent_design_not_accep_9_10_2002.asp "Intelligent Design" Not Accepted by Most Scientists], National Center for Science Education website, [[September 10]], [[2002]].</ref> Behe has been accused of using an "argument by lack of imagination", and Behe himself acknowledges that simply because scientists cannot currently see how an "irreducibly complex" organism could evolve, it does not prove that there is no possible way for it to have occurred. |

|||

Irreducible complexity is at its core an argument against evolution. If truly irreducible systems were found, the argument is that [[intelligent design]] is the correct explanation for their existence. However, this conclusion is based on the assumption that current [[evolution]]ary theory and intelligent design are the only two valid models to explain life, a [[false dilemma]].<ref>[http://www.talkdesign.org/faqs/icdmyst/ICDmyst.html IC and Evolution] makes the point that: if "irreducible complexity" is tautologically redefined to allow a valid argument that [[intelligent design]] is the correct explanation for life then there is no such thing as "irreducible complexity" in the mechanisms of life; while, if we use the unmodified original definition then "irreducible complexity" has nothing whatever to do with evolution.</ref> |

|||

==Irreducible complexity in the Dover trial== |

|||

While testifying at the [[Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District|Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District trial]] Behe conceded that there are no peer-reviewed papers supporting his claims that complex molecular systems, like the bacterial flagellum, the blood-clotting cascade, and the immune system, were intelligently designed nor are there any peer-reviewed articles supporting his argument that certain complex molecular structures are "irreducibly complex."<ref name="Kitzmiller_ruling_ID_science" /> |

|||

In the final ruling of Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, Judge Jones specifically singled out Behe and irreducible complexity:<ref name=Kitzmiller_ruling_ID_science>[[s:Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District/4:Whether ID Is Science|Memorandum Opinion, Judge John E. Jones III, Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District]]</ref> |

|||

* "Professor Behe admitted in "Reply to My Critics" that there was a defect in his view of irreducible complexity because, while it purports to be a challenge to natural selection, it does not actually address "the task facing natural selection." and that "Professor Behe wrote that he hoped to "repair this defect in future work..." (Page 73) |

|||

* "As expert testimony revealed, the qualification on what is meant by "irreducible complexity" renders it meaningless as a criticism of evolution. (3:40 (Miller)). In fact, the theory of evolution proffers exaptation as a well-recognized, well-documented explanation for how systems with multiple parts could have evolved through natural means." (Page 74) |

|||

* "By defining irreducible complexity in the way that he has, Professor Behe attempts to exclude the phenomenon of exaptation by definitional fiat, ignoring as he does so abundant evidence which refutes his argument. Notably, the [[United States National Academy of Sciences|NAS]] has rejected Professor Behe’s claim for irreducible complexity..." (Page 75) |

|||

* "As irreducible complexity is only a negative argument against evolution, it is refutable and accordingly testable, unlike ID [Intelligent Design], by showing that there are intermediate structures with selectable functions that could have evolved into the allegedly irreducibly complex systems. (2:15-16 (Miller)). Importantly, however, the fact that the negative argument of irreducible complexity is testable does not make testable the argument for ID. (2:15 (Miller); 5:39 (Pennock)). Professor Behe has applied the concept of irreducible complexity to only a few select systems: (1) the bacterial flagellum; (2) the blood-clotting cascade; and (3) the immune system. Contrary to Professor Behe’s assertions with respect to these few biochemical systems among the myriad existing in nature, however, Dr. Miller presented evidence, based upon peer-reviewed studies, that they are not in fact irreducibly complex." (Page 76) |

|||

* "...on cross-examination, Professor Behe was questioned concerning his 1996 claim that science would never find an evolutionary explanation for the immune system. He was presented with fifty-eight peer-reviewed publications, nine books, and several immunology textbook chapters about the evolution of the immune system; however, he simply insisted that this was still not sufficient evidence of evolution, and that it was not "good enough." (23:19 (Behe))." (Page 78) |

|||

* "We therefore find that Professor Behe’s claim for irreducible complexity has been refuted in peer-reviewed research papers and has been rejected by the scientific community at large. (17:45-46 (Padian); 3:99 (Miller)). Additionally, even if irreducible complexity had not been rejected, it still does not support ID as it is merely a test for evolution, not design. (2:15, 2:35-40 (Miller); 28:63-66 (Fuller)). We will now consider the purportedly “positive argument” for design encompassed in the phrase used numerous times by Professors Behe and Minnich throughout their expert testimony, which is the “purposeful arrangement of parts.” Professor Behe summarized the argument as follows: We infer design when we see parts that appear to be arranged for a purpose. The strength of the inference is quantitative; the more parts that are arranged, the more intricately they interact, the stronger is our confidence in design. The appearance of design in aspects of biology is overwhelming. Since nothing other than an intelligent cause has been demonstrated to be able to yield such a strong appearance of design, Darwinian claims notwithstanding, the conclusion that the design seen in life is real design is rationally justified. (18:90-91, 18:109-10 (Behe); 37:50 (Minnich)). As previously indicated, this argument is merely a restatement of the [[William Paley|Reverend William Paley]]’s argument applied at the cell level. Minnich, Behe, and Paley reach the same conclusion, that complex organisms must have been designed using the same reasoning, except that Professors Behe and Minnich refuse to identify the designer, whereas Paley inferred from the presence of design that it was God. (1:6- 7 (Miller); 38:44, 57 (Minnich)). Expert testimony revealed that this inductive argument is not scientific and as admitted by Professor Behe, can never be ruled out. (2:40 (Miller); 22:101 (Behe); 3:99 (Miller))." (Pages 79-80) |

|||

== Notes and references == |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

== Additional references == |

|||

* Behe, Michael (1996). ''[[Darwin's Black Box]]''. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-83493-6 |

|||

* Denton, Michael (1986). ''[[Evolution: A Theory in Crisis]]''. Adler & Adler. |

|||

* {{cite journal | author=Macnab RM | title=Type III flagellar protein export and flagellar assembly | journal=Biochim Biophys Acta | year=2004 | pages=207–17 | volume=1694 | issue=1-3 | pmid=15546667 | doi=10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.005}} |

|||

* {{cite journal|author=Ruben, J.A.; Jones, T.D.; Geist, N.R.; & Hillenius, W.J.|date=[[November 14]], [[1997]]|title=Lung Structure and Ventilation in Theropod Dinosaurs and Early Birds|journal=Science|volume=278|issue=5341|pages=1267–1270|doi=10.1126/science.278.5341.1267}} |

|||

* Sunderland, Luther D. (March 1976). Miraculous Design in Woodpeckers. ''Creation Research Society Quarterly''. |

|||

* [http://www.carlzimmer.com/articles/2005/articles_2005_Avida.html Testing Darwin] [[Discover Magazine]] [http://www.discovermagazine.com/issues/feb-05/cover/ Vol. 26 No. 02] | February 2005 |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{commons|Andreas Vesalius}} |

|||

* Himma, Kenneth Einar. [http://www.iep.utm.edu/d/design.htm Design Arguments for the Existence of God]. ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. |

|||

* [http://archive.nlm.nih.gov/proj/ttp/books.htm Page through a virtual copy of Vesalius's ''De Humanis Corporis Fabrica''] |

|||

* [http://www.vub.ac.be/VECO/bveco/ Vesalius College in Brussels] |

|||

;In support |

|||

* [http://link.library.utoronto.ca/anatomia/ Anatomia 1522-1867: Anatomical Plates from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library] |

|||

*[http://www.arn.org/authors/behe.html Michael J. Behe home page] |

|||

*[http://www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command=view&id=3408&program=DI%20Main%20Page%20-%20News&callingPage=discoMainPage About Irreducible Complexity] [[Discovery Institute]] |

|||

*[http://www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command=view&id=3419 How to Explain Irreducible Complexity -- A Lab Manual] [[Discovery Institute]] |

|||

*[http://www.icr.org/pdf/af/af0312.pdf Institute for Creation Research] (pdf) |

|||

*[http://www.iscid.org/papers/Dembski_IrreducibleComplexityRevisited_011404.pdf Irreducible Complexity Revisited] (pdf) |

|||

*[http://www.iscid.org/papers/Behe_ReplyToCritics_121201.pdf Behe's Reply to his Critics] (pdf) |

|||

*[http://www.idthefuture.com/2005/10/chris_adami_we_were_testing_behe_s_argum.html Response to Avida computer simulations] |

|||

;In opposition |

|||

*[http://www.philoonline.org/library/shanks_4_1.htm Behe, Biochemistry, and the Invisible Hand] |

|||

*[http://yalepress.yale.edu/yupbooks/book.asp?isbn=0300108656 Facilitated Variation] |

|||

*[http://www.bostonreview.net/BR21.6/orr.html Darwin vs. Intelligent Design (again), by H. Allen Orr (review of Darwin's Black Box)] |

|||

*[http://www.talkorigins.org Talk.origins archive] (see [[talk.origins]]) |

|||

**[http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/behe.html Irreducible Complexity and Michael Behe: Do Biochemical Machines Show Intelligent Design?] |

|||

**[http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/behe/review.html Darwin's Black Box: Irreducible Complexity or Irreproducible Irreducibility?] by Keith Robinson |

|||

**[http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/behe/icsic.html Is the Complement System Irreducibly Complex?] by Mike Coon |

|||

**[http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/genalg/genalg.html Genetic Algorithms] (Genetic algorithms have produced irreducibly complex solutions to real problems.) |

|||

**[http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/bombardier.html Discussion of the Bombardier Beetle] at Talk.origins |

|||

*[http://www.talkdesign.org TalkDesign.org] (sister site to talk.origins archive on [[intelligent design]]) |

|||

**[http://www.talkdesign.org/faqs/icdmyst/ICDmyst.html Irreducible complexity demystified] by Pete Dunkelberg. |

|||

*[http://www.millerandlevine.com Professor Kenneth R. Miller's textbook website] |

|||

**[http://www.millerandlevine.com/km/evol/DI/clot/Clotting.html A Darwinian explanation of the blood clotting cascade] |

|||

*[http://www.millerandlevine.com/km/evol/design2/article.html "The Flagellum Unspun: The Collapse of "Irreducible Complexity"] by Professor Miller |

|||

*[http://www.berteig.org/mishkin/IrreducibleComplexity.html A rigorous mathematical analysis of the concept of irreducible complexity] by Mishkin Berteig. |

|||

*[http://www.pamd.uscourts.gov/kitzmiller/kitzmiller_342.pdf PDF. 139 page in-depth analysis of Intelligent Design, Irreducible Complexity, and the book "Of Pandas and People" by a judge and based on expert testimony] |

|||

*[http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/articles/050530fa_fact Devolution: Why intelligent design isn't] ([[The New Yorker]]) |

|||

*[http://www.chicagotribune.com/technology/chi-0602130210feb13,1,1538105.story?page=1&ctrack=1&cset=true Unlocking cell secrets bolsters evolutionists] ([[Chicago Tribune]]) |

|||

*[http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2843/is_6_29/ai_n15930875 Does irreducible complexity imply Intelligent Design?] by Mark Perakh |

|||

*[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/library/01/1/l_011_01.html Evolution of the Eye (Video)] Zoologist Dan-Erik Nilsson demonstrates eye evolution through intermediate stages with working model. ([[PBS]]) |

|||

{{Persondata |

|||

{{creationism}} |

|||

|NAME=Vesalius, Andreas |

|||

|SHORT DESCRIPTION=Early anatomist |

|||

|DATE OF BIRTH=December 31, 1514 |

|||

|PLACE OF BIRTH=Brussels, Belgium |

|||

|DATE OF DEATH=October 15, 1564 |

|||

|PLACE OF DEATH=Zakynthos, Greece |

|||

}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Vesalius, Andreas}} |

|||

[[Category:Creationist objections to evolution]] |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:1514 births]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:1564 deaths]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Anatomists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Belgian physicians]] |

||

[[Category:History of medicine]] |

|||

[[Category:History of anatomy]] |

|||

[[Category:History of neuroscience]] |

|||

[[Category:Leuven alumni before 1968]] |

|||

[[bg:Андреас Везалий]] |

|||

[[da:Irreducibel kompleksitet]] |

|||

[[cs:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[de:Nichtreduzierbare Komplexität]] |

|||

[[da:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[fr:Complexité irréductible]] |

|||

[[de:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[it:Complessità irriducibile]] |

|||

[[et:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[nl:Onherleidbare complexiteit]] |

|||

[[el:Ανδρέας Βεσάλιος]] |

|||

[[pl:Nieredukowalna złożoność]] |

|||

[[es:Andrés Vesalio]] |

|||

[[fi:Palautumaton monimutkaisuus]] |

|||

[[fa:آندره وزالیوس]] |

|||

[[sv:Irreducibel komplexitet]] |

|||

[[fr:André Vésale]] |

|||

[[zh:不可化約的複雜性]] |

|||

[[id:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[it:Andrea Vesalio]] |

|||

[[he:אנדריאס וסאליוס]] |

|||

[[ku:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[la:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[nl:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[ja:アンドレアス・ヴェサリウス]] |

|||

[[no:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[pl:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[pt:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[ro:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[ru:Везалий, Андреас]] |

|||

[[sk:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[sl:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[fi:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[sv:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

[[th:แอนเดรียส เวซาเลียส]] |

|||

[[tr:Andreas Vesalius]] |

|||

Revision as of 15:52, 13 October 2008

Andreas Vesalius | |

|---|---|

Portrait from the Fabrica | |

| Born | December 31, 1514 Brussels, Belgium |

| Died | October 15, 1564 Zakynthos, Greece |

Andreas Vesalius (Brussels, December 31, 1514 - Zakynthos, October 15, 1564) was an anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Workings of the Human Body). Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy.

Vesalius is the latinized form of Andreas van Wesel. He is sometimes also referred to as Andreas Vesal.

Early life and education

Vesalius was born in Brussels, then in the Habsburg Netherlands, to a family of physicians. His great-grandfather, Jan van Wesel, probably born in Wesel, received his medical degree from the University of Pavia and taught medicine in 1428 at the then newly founded University of Leuven. His grandfather, Everard van Wesel, was the Royal Physician of Emperor Maximilian, while his father, Andries van Wesel, went on to serve as apothecary to Maximillian, and later a valet de chambre to his successor Charles V. Andries encouraged his son to continue in the family tradition, and enrolled him in the Brethren of the Common Life in Brussels to learn Greek and Latin according to standards of the era.

In 1528 Vesalius entered the University of Louvain (Pedagogium Castrensis) taking arts, but when his father was appointed as the Valet de Chambre in 1532, he decided to pursue a career in medicine at the University of Paris, where he moved in 1533. Here he studied the theories of Galen under the auspices of Jacques Dubois (Jacobus Sylvius) and Jean Fernel. It was during this time that he developed his interest in anatomy, and was often found examining bones at the Cemetery of the Innocents.