Change ringing: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

Change ringing can also be carried out on [[handbell]]s (small bells, generally weighing only a few hundred grams). A few groups of tower bell-ringers use handbells to practise (in which case, just as in the tower, one ringer handles one bell). Some bell-ringers pursue handbell ringing as an activity in its own right, in which case each ringer usually handles two or more bells. |

Change ringing can also be carried out on [[handbell]]s (small bells, generally weighing only a few hundred grams). A few groups of tower bell-ringers use handbells to practise (in which case, just as in the tower, one ringer handles one bell). Some bell-ringers pursue handbell ringing as an activity in its own right, in which case each ringer usually handles two or more bells. |

||

Handbell ringing was particularly popular during the [[Second World War]] when church bells were not rung. Ringers unable to use the church bells were obliged to practice their art on handbells, often in |

Handbell ringing was particularly popular during the [[Second World War]] when church bells were not rung. Ringers unable to use the church bells were obliged to practice their art on handbells, often in their own homes. Although the ringers returned to the towers as soon as the war was over, for a number of years after the war handbell ringing was extremely popular, and most ringers who lived through the war were competent handbell ringers. |

||

== Mathematics of change ringing == |

== Mathematics of change ringing == |

||

Revision as of 21:20, 6 March 2006

Change ringing is the art of ringing a set of tuned bells in a series of mathematical patterns called "changes", without attempting to ring a conventional tune. It originated in England and remains most popular there today, as well as in countries around the world with British influence. On continental Europe, by contrast, a different form of campanology, carillon ringing (which does aim at recognizable melodies), is much more popular. Like carillons, change-ringing bells are often found in church towers; but the two methods are entirely different not only in their musical aims but also in their physical set-ups. A carillon consists of a large number of bells which are struck by hammers all tied in to a central framework so that one carilloneur can control them all; change ringing, by contrast, uses a smaller number of bells and typically requires a ringer for each bell.

Mechanics of change ringing on tower bells

A bell tower in which change ringing takes place can contain any number of bells, in theory, but typically contain up to sixteen bells. Six or eight bells are more common for the average church. The bell highest in pitch is known as the treble and the bell lowest in pitch is called the tenor. For convenience, the bells are numbered, with the treble being number 1 and the other bells numbered by their pitch — 2,3,4, etc. — sequentially down the scale. (This system often seems counterintuitive to musicians, who are used to a numbering which ascends along with pitch.) The bells are usually tuned to a diatonic major scale, with the tenor bell being the tonic (or key) note of the scale.

The bellringers typically stand in a circle around the ringing room, each managing the rope for his or her bell above. Each bell is suspended from a headstock, allowing it to rotate through just over 360 degrees; the headstock is fitted with a wooden wheel around which the rope is wrapped.

During a session of ringing the bell sits poised upside-down while it awaits its turn to ring. By pulling the rope, the ringer upsets the balance and the bell swings down then back up again on the other side, describing slightly more than a 360-degree circle. During the swing, the clapper inside the bell will have struck the soundbow, making the bell resonate once. This action constitutes the handstroke, at the end of which the ringer's arms are above his head and a portion of the bell-rope is wrapped around almost the entirety of the wheel. After a pause, the ringer again pulls the rope and the bell revolves in the opposite direction, returning to its original position, again sounding once. This is the backstroke.

Although ringing certainly involves some physical exertion, the successful ringer is one with practised skill rather than mere brute force; after all, even small bells are typically much heavier than the people ringing them, and can only be rung at all because they are well-balanced in their frames. The heaviest bell hung for full-circle ringing is in Liverpool Cathedral and weighs over four imperial tons. Despite this colossal weight, it can be safely rung by one (experienced) ringer. While heavier bells exist (for example Big Ben), they are generally only chimed, either by swinging the bell slightly or using a mechanical hammer.

Handbells

Change ringing can also be carried out on handbells (small bells, generally weighing only a few hundred grams). A few groups of tower bell-ringers use handbells to practise (in which case, just as in the tower, one ringer handles one bell). Some bell-ringers pursue handbell ringing as an activity in its own right, in which case each ringer usually handles two or more bells.

Handbell ringing was particularly popular during the Second World War when church bells were not rung. Ringers unable to use the church bells were obliged to practice their art on handbells, often in their own homes. Although the ringers returned to the towers as soon as the war was over, for a number of years after the war handbell ringing was extremely popular, and most ringers who lived through the war were competent handbell ringers.

Mathematics of change ringing

The simplest way to use a set of bells is ringing rounds, which is sounding the bells repeatedly in sequence: 1, 2, 3, etc.. Musicians will recognise this as a portion of a descending scale. Ringers typically start with rounds and then begin to vary the bells' order, moving on to a series of distinct rows. Each row (or change) is a specific permutation of the bells (for example 123456 or 531246) — that is to say, it includes each bell rung once and only once, the difference from row to row being the order in which the bells follow one another. There are two ways to achieve this: swapping one pair of bells at a time, with one ringer (the conductor) telling everyone else which pair to swap, or swapping multiple pairs of bells to a prescribed pattern, with the conductor just calling the method. The former is known as call change ringing and the latter as method ringing.

Call change ringing

Call change ringing is practised as a stepping stone to method ringing as many learners find it is easier to do. However, in the county of Devon, England there are many towers that practise this form of ringing exclusively. Hence call change ringing is also known as "Devon style". The bells are made to change order by the conductor calling a pair of bells to swap. Each call takes the form of two numbers corresponding to the bells which are to change. For example, if the bells start in the order 135246 and the conductor calls "5 to 2" (which is shorthand for "bell number 5 ring after bell number 2") the resulting order of the bells is 132546. This, the accepted way of calling in Devon and many towers elsewhere, is known as calling up as the bell corresponding to the number called first moves up after the second bell. Call changes can also be called by calling down; in the example above the call would become "2 to 3" for the same result.

For a peal of call changes the bells are firstly rung up in peal (all the bells ringing together in rounds, known as the rise), a number of changes are rung (at the top) and then the bells are rung down in peal (again all the bells ringing together in rounds, known as the lower). All this takes anything from 10 to 30 minutes depending on the number of changes called and the number of bells being rung.

Method ringing

Method Ringing is what most people mean by "Change Ringing". The ultimate goal of method ringing is to ring the bells in every possible order without repeating; this is called an "extent" (in the past this was sometimes referred to as a "full peal"). If a tower has bells, they will have (read factorial) possible permutations, a number that becomes quite large as grows. For example, while six bells have 720 permutations, 8 bells have 40,320; furthermore, 10! = 3,628,800, and 12! = 479,001,600.

Estimating two seconds for each change (a reasonable pace), we find that while an extent on 6 bells can be accomplished in half an hour, a full peal on 8 bells should take nearly twenty-two and a half hours (when in 1963 ringers in Loughborough accomplished this rarest of feats, it actually took them just under 18 hours), while an extent on 12 bells would take over thirty years!

Ringing an extent is an advanced form of method ringing and less experienced ringers will generally ring shorter touches or plain-courses. These do not ring every possible permutation but they still do not repeat any.

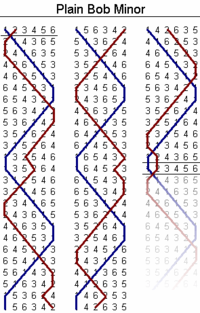

Various algorithms or methods have been developed for ringers to learn conceptually. They will dictate the bells "movements" and, if followed correctly, will prevent them from repeating any rows. These methods follow basic patterns, but a caller or conductor will occasionally call out to tell the ringers to make a slight variation to the pattern.

Learning to Ring

Change Ringing is a relatively complex task and it can take many years for someone to become proficient, although this varies from person to person. They are almost always trained by a more experienced ringer, although there are some self-taught ringers. Ringing is also very "open-ended" and there are always more stages and skills to master. Different teachers will also have different methods of teaching.

Change Ringing is also very "open-ended" and there are always new methods to learn, new peals to call and new skills to be mastered. For example, A ringer can learn to ring with just one hand; then he can learn to ring another bell with his other hand; then he will learn to ring a peal on two bells; etc.

For the top ringers, there is the milestone of ringing 1000 successful peals).

Striking and striking competitions

Although neither call change nor method ringing produces conventional tunes, it is still the aim of the ringers to produce a pleasant sound. The most pleasant sounds are achieved when the gap between each bell is always the same and the bells do not clash by sounding at the same instant. This achievement is known as good striking.

Striking competitions are held where various bands of ringers attempt to ring with their best striking. They are judged on their number of faults (striking errors); the band with the least number of faults wins.

Many regional ringing associations have annual striking competitions for bands from their region. There are also several nation-wide striking competitions, including the prestigious National Twelve-Bell competition [1]. These competitions may have separate awards for bands ringing on 6, 8, 10 or 12 bells, or for call change and method ringing. The competition organisers may designate a set piece (a particular method or sequence of call changes) which all bands must ring, or else allow each band to ring their best piece.

In a Devon call change competition, all the teams that enter the competition ring the same set of call changes, usually the so called "sixty on thirds", complete with a rise and lower in not less than 15 minutes on six bells. The most prestigious of all the competitions in Devon are the two Devon Association of Ringers finals, The Devon Major Final for towers with six or fewer bells, and The Devon 8-Bell Final for towers with eight or more bells (there are no seven-bell towers). These have been held around Easter every year since the 1920s, and the most successful teams in the finals of recent years have been Eggbuckland, a tower in the city of Plymouth, in the Major Final and Kingsteignton in the 8-Bell Final. Due to the number of competitions, ringing by bands from Devon's more successful towers is reckoned to have some of the best striking in the country.

In 2000 an annual National Call Change competition was initiated with the hope of gaining more interest in call change ringing in the rest of the UK. However, attendance from teams outside Devon has been limited, largely due to the competition being held mainly in eastern Devon. In 2004 the competition was won by Eggbuckland's first team, and a team from Hampshire beat a Devon team. This was the first time a Devon team had been beaten by a team from outside the county in this competition.

History and modern culture of change ringing

Change ringing began in England in the early part of the 17th century. The techniques used today are extremely similar to those developed at that time, with the only major innovations being the use of ball bearings to improve the ease of movement of the bells, and the introduction of Simpson tuning in the early 20th century to improve the intonation of the bells.

The first recorded peal was rung on May 2, 1715 at St Peter Mancroft, Norwich, England, and was of the method today known as Plain Bob Triples. Today change-ringing can frequently be heard from towers all over that country and around the world, often before or after a church service or wedding. While on these everyday occasions the ringers must usually content themselves with shorter "touches," for special occasions a quarter-peal is often rung; a quarter-peal of triples will last something on the order of 45 minutes. Periodically, for a special occasion (or sometimes just for fun) a group of ringers might attempt a peal (the most concise of which will last approximately three hours); if they succeed they occasionally mark the accomplishment with a peal board on the wall of the ringing chamber.

The longest (in terms of changes) peal ever rung was on handbells in Coventry on 2 October, 2004. It consisted of 50400 changes (10 times the changes in a standard peal) of 70 different "Treble Dodging Minor" methods, and took over 17 hours to ring. This was generally regarded as a most impressive achievement (even amongst those who questioned the performers' sanity), bearing in mind that no external aids can be used when ringing a peal. In particular, the conductor had to memorise and then recall the entire composition, in addition to ringing two of the bells.

The Central Council of Church Bell Ringers is the representative body for all those who ring bells in the traditional English style around the world, and was founded in 1891. Today the Council represents 66 affiliated societies, which cover all parts of the British Isles as well as centres of ringing in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, USA, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Verona in Italy.

The ringing community has its own weekly newspaper, the Ringing World, which is also the official journal of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Published weekly since 1911 it includes articles and news relating to bellringing and the bellringing community, as well as publishing records of achievements such as peals and quarter-peals. These may only be included if they meet the Central Council's definitions and rules, which therefore have widespread acceptance.

In the world of literature, Dorothy L. Sayers's mystery novel The Nine Tailors is famous for the central part played by change ringing. Much of the action centers around a bell tower and the peals rung in it, and to draw the reader in Sayers takes care to explain change ringing and analyze its improbable popularity; quotations from the book are popular with ringers. Moreover, the entire book is infused with an air of change ringing to the extent that her chapter titles all employ campanalogical terminology; and indeed, one of the book's conceits is that it is a sort of multi-part peal.

See also

External links

- ringing.info, a wide-ranging and well-organized compendium of ringing links

- Central Council of Church Bell Ringers

- Ringing World newspaper

- Central Council decisions — scroll down the page to see the council's definition of a peal

- Campanophile - the Ringers' Resource

- ringing.org

- free ringing practice page

- The North American Guild of Change Ringers

- The Australian and New Zealand Association of Bellringers

- "Abel" Bell ringing simulator programme