Anta (architecture): Difference between revisions

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

===Doric anta capital=== |

===Doric anta capital=== |

||

The Doric capital was designed in the continuity of the wall [[cornice]]. It is characterized by a broad neck, a beak molding and an [[abacus]]. Decoration is usually very sparse, except for the capitals displaying a transition with the Ionic order.<ref>Greek Architecture, Marquand, 1909 p.74 [http://www.survivorlibrary.com/library/greek_architecture-marquand_1909.pdf]</ref> |

The [[Doric order|Doric]] capital was designed in the continuity of the wall [[cornice]]. It is characterized by a broad neck, a beak molding and an [[abacus]]. Decoration is usually very sparse, except for the capitals displaying a transition with the Ionic order.<ref>Greek Architecture, Marquand, 1909 p.74 [http://www.survivorlibrary.com/library/greek_architecture-marquand_1909.pdf]</ref> |

||

===Ionic anta capital=== |

===Ionic anta capital=== |

||

Revision as of 08:17, 10 November 2016

An anta (pl. antæ) (Latin, possibly from ante, 'before' or 'in front of'), or sometimes parastade is an architectural term describing the posts or pillars on either side of a doorway or entrance of a Greek temple - the slightly projecting piers which terminate the walls of the naos.[1] It differs from the pilaster, which is purely decorative, and does not have the structural support function of the anta.

Anta

In contrast to columns or pillars, antae are directly connected with the walls of a temple. They owe their origin to the vertical posts of timber employed in the early, more primitive palaces or temples of Greece, as at Tiryns and in the Temple of Hera at Olympia. They were used as load-bearing structures to carry the roof timbers, as no reliance could be placed on walls built with unburnt brick or in rubble masonry with clay mortar. Later, they became more decorative as the materials used for wall construction became sufficient to support the structure.[2]

When there are columns between antae, as in a porch facade, rather than a solid wall, the columns are said to be in antis. (See temple.)[2]

Anta capitals

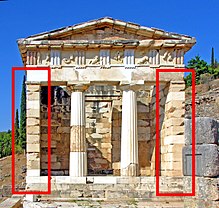

Right image: Doric anta capital at the Athenian Treasury (circa 500 BCE).

The anta is generally crowned by a stone block designed to spread the load from superstructure (entablature) it supports, called an "anta capitals" when it is structural, or sometimes "pilaster capital" if it is only decorative as often during the Roman period. In order not to protude unduly from the wall, these anta capitals usually display a rather flat surface, so that the capital has more or less a brick-shaped structure overall. The anta capital can be more or less decorated depending on the artistic order it belongs to, with designs, at least in Greek architecture, often quite different from the design of the column capitals it stands next to. This difference disappeared with Roman times, when anta or pilaster capitals have design very similar to those of the column capitals.[3][4]

Doric anta capital

The Doric capital was designed in the continuity of the wall cornice. It is characterized by a broad neck, a beak molding and an abacus. Decoration is usually very sparse, except for the capitals displaying a transition with the Ionic order.[5]

Ionic anta capital

Right image: A characteristically rectangular Ionic anta capital, with extensive bands of floral patterns in prolongation of adjoining friezes at the Erechtheion (circa 410 BCE).

The Ionic anta capital is very different in that it is very rich in moldings. It remains however essentially brick-shaped. The Ionic anta capitals of the Erechtheion take the shape of very decorated brick-shaped capitals, with designs essentially in the continuity of wall cornices, with some additional horizontal moldings.

Some temples in Ionia tend to have a very different design of anta capital, flat at the fronts but with volutes on the side, giving them the shape of sofas, hence the name they sometimes take of "sofa capitals".[6] In this case the sides of the capital broaden upward, in a shape reminiscent of a couch or sofa.[7] These capital can also be described as pilaster capitals, which, strictly speaking, are normally decorative rather than structural components.[8]

-

Anta capital, Didyma.

-

Anta capital from Miletus (front view).

-

Anta capital at the Temple of Apollo in Didyma, front and profile. 4th century BCE.

-

The Pataliputra capital, a Hellenistic anta capital from India (3rd century BCE).

Corinthian anta capital

Right image: Corinthian anta capital at the Niha Bekaa Roman Temple, 1st century AD.

Corinthian anta capital tend to be much closer to the designs of the columns, although often with a flattened composition: during the Greek period, Acanthus leaves are crowned by a central motif, such as a palmette, itself bracketed by volutes. This design was widely adopted in India for Indo-Corinthian capitals.

During the Greek period, anta capitals had designs different from those of colum capital, but during Roman and later times this difference disappeared and both column and anta capitals has the same types of designs.[9][10] At the same time, decorative pilaster designs multiplied during Roman times, so that many of the Corinthian anta capital designs are actually purely decorative pilaster designs.

Distyle in antis

Early Greek temples such as the 6th century Siphnian Treasury had antae on both side of the porch, framing a set of columns (a disposition named "distyle in antis", meaning "two columns in between antae"). This was an early type of temple construction (the "distyle temple") meant to reinforce weak wall construction by head posts, the antae. Sometimes, the walls were in brick, and thus needed this kind of reinforcement, as in the Heraeum of Olympia (c. 600 BCE).[11]

-

Early Greek temples such as the Siphnian Treasury had antae on both side of the porch, framing a set of columns.

-

Front view of the Siphnian Treasury with framing antae.

-

The Athenian Treasury in Delphi is also a distyle in antis design.

Notes

- ^ Roth 1993, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911, p. 88.

- ^ A handbook of ornament, by Franz-Sales Meyer [1]

- ^ The Classical Language of Architecture by John Summerson, p.47 "Anta" entry [2]

- ^ Greek Architecture, Marquand, 1909 p.74 [3]

- ^ Greek Architecture, Marquand, 1909 p.74-76 [4]

- ^ Architectural Elements, Emory University

- ^ "The New and Improved Practical Builder: Masonery, bricklaying, plastering" Peter Nicholson, Thomas Kelly, 1837, p.68 [5]

- ^ A handbook of ornament, by Franz-Sales Meyer [6]

- ^ The Classical Language of Architecture by John Summerson, p.47 "Anta" entry [7]

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, Anta entry [8]

References

- Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antae". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 88.