Henri Bergé

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Henri Bergé | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 October 1870 Diarville |

| Died | 26 November 1937 Nancy |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Designer, illustrator, paintor |

| Movement | Ecole de Nancy, Art Nouveau |

| Signature | |

| |

Henri Bergé (October 14, 1870 – October 26, 1937) was a French designer and illustrator part of the Art Nouveau movement.[1]

Biography[edit]

The son of a lace manufacturer, Henri Bergé received an artistic education at l'École des Beaux-Arts in Nancy, where he was a student of the painter Jules Larcher.[2]

In 1897, he joined Daum, a crystal studio based in Nancy, France, and became a leader in decorative glass. Bergé become head decorator, replacing Jacques Gruber.[3]

He is mostly known for his Floral Encyclopedia, which brought together his studies of plants for the Daum's manufacturing of art glass and crystal objects.[4]

École de Nancy[edit]

Henri Bergé was long associated with the École de Nancy, also named "the provincial alliance of the industries of art," which was born from the collaboration of the main actors and promoters of Lorraine decorative arts. Émile Gallé was its president, while Louis Majorelle, Antonin Daum, and Eugène Vallin were vice presidents . Upon its creation on February 13, 1901, Henri Bergé was one of the members of the steering committee alongside other notable local figures, including Jacques Gruber, Louis Hestaux, Charles Fridrich and Victor Prouvé.[5]

Mainly known for his drawings, Henri Bergé followed the values held by the École de Nancy and taught in several schools during his career. In 1894, he supervised the lessons of the Daum modeling and drawing house school. In 1895, he took over as co-director of this school alongside Jacques Gruber.[6]

Afterwards, Henri Bergé became "Director of Decor Learning Lessons.". He therefore success Jacques Gruber as master decorator within the Daum manufacture. He was responsible for the creation of pieces (designing shapes and serial but also unique parts) and the creation and control of the pouncing patterns.[6]

Henri Bergé worked with Antonin Daum until his death in 1937; the designer was also a professor at other institutions. He gave lessons at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts but also at the Ecole professionnelle de l'Est in Nancy. This was a school for applied arts. Its goal was to compete with the Beaux-Arts schools, where teaching no longer meets the needs of industrial art. During the World War I, Henri Bergé also taught at the Henri-Poincaré high school.[6]

Art Nouveau[edit]

Techniques and nature observation[edit]

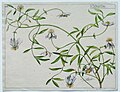

Henri Bergé's works show a precise study of plants. Christophe Bardin describes Henri Bergé's observational work as "a direct observation of nature by travelling the surrounding countryside or using the botanical gardens and greenhouses of Nancy to discover more exotic species, followed by a drawing work" [7].

Bergé often visited the botanical garden of Sainte Catherine and the greenhouse of the nurseryman Victor Lemoine in Nancy.[6] In addition, Bergé was a member of the central horticultural society of Nancy, which shows his huge interest in plants.[8] This society played a major role for the artists of the École de Nancy, who were strongly influenced by nature.

Much like some members of the École de Nancy, such as Louis Majorelle or Eugène Corbin, Henri Bergé also used photography in addition to his drawing to help his creative work. This practice allowed him to create models with great naturalism. These photographs could have been taken either outdoors or in a studio, for example, by isolating a plant on a neutral background. A series of photographic plaques were discovered in the house of Suzanne Bergé, the artist's daughter.[9]

Daum studio[edit]

Thus, as the artistic director of the factory, Henri Bergé was an essential collaborator in the Daum company. Daum's goal was to produce decorative pieces in a more industrial way by mass-copying patterns. Henri Bergé developed a unique way of affixing his drawings to the pieces. He created pouncing patterns. On tracing paper, he adapted a reusable pouncing pattern for the factory's decorators.[6] They could then saw the guidelines to follow while creating the vase. It is a practical and economical technique; it allowed mass production of the patterns designed by Bergé.[10]

The diffusion of Bergé's models was also incorporated into his lessons at the Daum School. I was also through the study of leaves and flowers made by the artist that the student's learned how to draw. The same leaf and flower study techniques were leveraged for other establishments where the professor taught.[6]

The works designed by Bergé represented the majority of the objects exposed by Daum during the Universal exhibition in 1900 in Paris.[11]

In 40 years of activity within the Daum manufacture, Henri Bergé built up a veritable collection of plants and floral motifs that he brought together in his Floral Encyclopedia. It was used as a source of motifs by the Daum manufacture until the 1920s.[11]

Floral Encyclopedia[edit]

Henri Bergé's drawings reflect the period's taste for Japonisme, the attraction of nature and volute and arabesque shapes.[6]

Bergé demonstrated dedicated scientific rigor.[12] In his art, it is possible to find many details, such as fruits, seeds, or even the different stages of flower blossoming. Some plates are sometimes accompanied by scientific indications and / or descriptions.[13]

Even if Bergé's production faithfully reflected nature, he never conceived his work as a true work of art. It does not seek the completeness of an encyclopedia. Its aims were mainly industrial. Its objective was the constitution of a stylistic fund to serve "beautiful functional models" to the Daum's workers.[6]

Collaboration with Almaric Walter.[edit]

Henri Bergé collaborated with Amalric Walter, who used his naturalist repertoire to make his glass pastes. Indeed, the production of Amalric Walter, largely inspired by the work of Bergé at Daum, was characterized by art nouveau pieces highlighting fauna and flora.[14]

Bergé did not hesitate to cast some insects and small animals for his collaboration with Amalric Walter.[2]

This collaboration was so important that in 1925,during the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, Henri Bergé received a gold medal for his work with Walter.[15]

Examples of works created during this collaboration

Works[edit]

- Henri Bergé produced numerous advertisements (e.g. for the Maison d'art de Lorraine) printed by Albert Begeret in Nancy, and subsequently printed by the Modern Graphic Art.[16]

An advertisement which promoted the opening of a mourning department at the Magasins Réunis in Nancy, by Henri Bergé, 20th century, Nancy, Palace of the Dukes of Lorraine. - He also illustrated advertisements for the old French stores chain called the Magasins réunis in Nancy.

- Bergé created several Art Nouveau stained-glass windows. Some were advertising stained glass windows such as in the brewery located on the ground floor of the Cure d'Air Trianon in Malzéville. The window panels presented the major beverage brands sold at the brewery.[17] Other stained-glass were more symbolic works of art, such as La Lecture preserved in the collection of the musée de l'École de Nancy.[18]

- Bergé also collaborated with Amalric Walter, a French glass-maker, and gave him several models, which Walter then used to make handcrafted glass pastes.[19]

- Henri Bergé produced watercolor studies which represented plants. These studies were grouped together in his Floral Encyclopedia. A collection of 85 of Bergé's drawings are kept at the musée de l'École de Nancy. Its was donated to the museum by the Pont-à-Mousson company in 1988[20]

References[edit]

- ^ "Relevé généalogique". Geneanet.

- ^ a b Hurstel, Jean (2000). "Amalric Walter (1870-1959), créateur de la pâte de verre à l'Ecole de Nancy dès 1904". Le Pays lorrain: Revue bimensuelle illustrée (in French): 188.

- ^ Cappa, Giuseppe (1998). Le génie verrier de l'Europe: témoignages: de l'historicisme à la modernité (in French). Hayen: Mardaga. p. 575.

- ^ Musée de l'Ecole de Nancy (1999). L'Ecole de Nancy,1899-1909. Art nouveau et industrie d'art (in French). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. p. 357.

- ^ Renaud, Patrick Charles (2009). Daum: du verre et des hommes (in French). Nancy: Place Stanislas Editions. p. 31. ISBN 978-2-35578-040-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bardin, Christophe (2004). Daum, 1878-1939 Une industrie d'art lorraine (in French). Strasbourg: Serpenoise. pp. 76–80.

- ^ Bardin, Christophe (2014), Cazalas, Inès; Froidefond, Marik (eds.), "Gallé/Daum, deux approches différentes du végétal comme source d'inspiration", Le Modèle végétal dans l’imaginaire contemporain, Configurations littéraires (in French), Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, pp. 75–83, ISBN 979-10-344-0491-9, retrieved 2024-02-25

- ^ Société centrale d'horticulture de Nancy (1933). Bulletin de la Société centrale d'horticulture de Nancy (in French). 1933. p. 17.

- ^ Thomas, Valérie; Perrin, Jérôme (2018). L'Ecole de Nancy. Art nouveau et industrie d'art (in French). Paris: Somogy éditions d'art (published 2014). p. 68.

- ^ Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy (1999). L'Ecole de Nancy, 1889-1909. Art nouveau et industrie d'art (in French). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. p. 243.

- ^ a b Bardin, Christophe (2000). Daum- Collection du musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy (in French). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. pp. 141–143. ISBN 2-7118-4036-0.

- ^ Frising, Michel (2015). L'Encyclopédie florale d'Henri Bergé. Art nouveau & écologie: Mélanges (PDF) (in French). pp. 134–140.

- ^ Frising Michel (2015). "L'Encyclopédie florale d'Henri Bergé" (PDF). Art nouveau & écologie: Mélanges: 135–140.

- ^ Thomas, Valérie; Perrin, Jérôme (2018). L'Ecole de Nancy. Art nouveau et industrie d'art (in French). Paris: Somogy éditions d'art. p. 70.

- ^ Bardin, Christophe (2004). Daum.1878-1939. Une industrie d'art lorraine (in French). Strasbourg: Serpenoise. p. 90.

- ^ Nancy, musée des Beaux-Arts (2018). L'Ecole de Nancy, Art nouveau et industrie d'art, Nancy, Musée des beaux-arts, 19 mai - 3 septembre 2018 (in French). Paris: Somogy éditions d'art.

- ^ Musée des Beaux-Arts (Nancy) (1999). L'Ecole de Nancy,1899-1909. Art nouveau et industrie d'art [exposition, Musée des Beaux-Arts] (in French). Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. p. 57. ISBN 2-7118-3843-9.

- ^ Musée de l'Ecole de Nancy. "Les vitraux emblèmes de l'Art Nouveau". Musée de l'Ecole de Nancy.

- ^ Bardin Christophe (2004). Daum.1878-1939. Une industrie d'art lorraine (in French). Metz: Editions Serpenoise. p. 97.

- ^ Barbier, Ludwig-Georges (1988). Henri Bergé: un don exceptionnel (in French). pp. 4–5.