Four-sided model

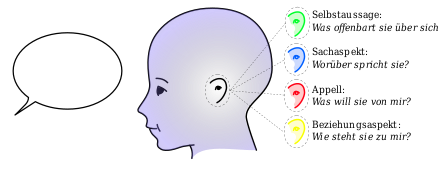

The four-sided model (also message square , communication square or four-ear model ) by Friedemann Schulz von Thun is a model of communication psychology with which a message is described under four aspects or levels: content, self-disclosure, relationship and appeal . These levels are also known as "four sides of a message". The model is used to describe communication that is disturbed by misunderstandings .

With the four-sided model, Schulz von Thun combines two psychological and language-theoretical analyzes. Paul Watzlawick postulated that every statement can be understood under a content aspect and a relationship aspect ( second axiom ). In the Organon model, the language theorist Karl Bühler described linguistic signs using three semantic functions: expression , appeal and representation . Such models are also known in linguistics as models of language functions .

The four sides of a message

The overarching goal of this modeling is to observe, describe and model how two people relate to one another through their communication. Schulz von Thun turns to the statements (the "news"). These can be viewed from four different directions and interpreted under four different assumptions - these are the four aspects or levels that Schulz von Thun calls the "sides of a message":

- Factual aspect

- the described matter ("content", "what I am informing about")

- Self-statement

- that which becomes clear from the message about the speaker ("self-revelation", "what I declare about myself")

- Relationship aspect

- what is revealed in the type of message about the relationship ("relationship", "what I think of you or how we relate to each other")

- appeal

- the one to which the recipient is to be induced (" appeal ", "what I want you to do")

In this way, the “message as the object of communication diagnosis ” can be used. Disturbances and conflicts arise when the sender and recipient interpret and weight the four levels differently. This leads to misunderstandings and, as a result, to conflicts . A well-known example, first used by Schulz von Thun in his main work Talking To Each Other, is a couple in the car in front of the traffic lights. The woman is at the wheel and the man says “You, the traffic light is green!” The woman replies: “Are you driving or am I driving?”. In this situation, the statement can be understood as follows on the four levels: as a reference to the traffic light that has just switched to green (factual level); as an invitation to drive off (appeal level), as the intention of the passenger to help the woman behind the wheel, or as a demonstration of the superiority of the passenger over the woman (relationship level); as an indication that the passenger is in a hurry and is impatient ( self-disclosure ). So the passenger can have put the weight of the message on the roll call. On the other hand, the driver could take the passenger's statement as a disparagement or paternalism.

With regard to the listener and his habits, Schulz von Thun is expanding the four-sided model into a "four-ears model". One ear each stands for the interpretation of one of the aspects: the “factual ear”, the “relationship ear”, the “self-disclosure ear” and the “appeal ear”.

Factual level / content

At the factual level, the speaker conveys data, facts and circumstances. The speaker's tasks are clarity and intelligibility of expression. With the "factual ear", the listener checks the message with the criteria of truth (true / untrue), relevance (of relevance / irrelevant) and sufficiency (sufficient / in need of addition). In a well-rehearsed team, this usually runs smoothly.

Self-disclosure

Every utterance causes an only partially conscious and intended self-expression and at the same time an unconscious, involuntary self- disclosure (see Johari window ). Each message can thus be used to interpret the personality of the speaker. The "self-revelation ear" of the listener listens to what is contained in the message about the speaker ( I-messages ). In contrast, “self-disclosure” refers to the verbal communication of personal and confidential thoughts, feelings or information; the content relates to yourself.

Relationship level

The relationship level expresses how the speaker and the listener relate to each other and how they assess each other. The speaker can - through the type of formulation, his body language, tone of voice and other things - show appreciation, respect, benevolence, indifference, contempt in relation to the other. Depending on what the listener perceives in the “relationship ear”, he feels either accepted or belittled, respected or patronized.

appeal

Those who express themselves usually also want to make a difference. With the appeal, the speaker wants the listener to do something or not to do something. Trying to exert influence can be overt or covert. Requests and requests are open. Covert causes are called manipulation . On the “roll call ear” the listener asks himself: “What should I think, do or feel now?”

Example of a communication disrupted by misunderstandings

To describe communication that is disturbed by misunderstanding on the various levels, Schulz von Thun describes the following situation as an example: A man and a woman are sitting at dinner. The man sees capers in the sauce and asks: "What is the green thing in the sauce?" He means on the different levels:

| Factual level: | There is something green there. |

| Self-revelation: | I do not know what it is. |

| Relationship: | You will know |

| Appeal: | Tell me what it is |

The woman understands the man on the different levels as follows:

| Factual level: | There is something green there. |

| Self-revelation: | I don't like the food. |

| Relationship: | You are a miserable cook! |

| Appeal: | Next time leave out the green! |

The woman answers irritably: "My God, if you don't like it here, you can go to eat somewhere else!"

News and messages contained therein

For Schulz von Thun, messages contain explicit and implicit messages. Examples of explicit messages at the factual level are: "It's very hot outside"; on the level of self-revelation: "I am ashamed"; on the relationship level: "I like you", on the level of influence: "get a beer!" Implicitly, the same messages can be interpreted from the following behavior, for example: someone enters the room and wipes their damp forehead; someone avoids the other's gaze; someone hugs his counterpart; someone says the beer has run out.

Messages can be viewed as congruent and incongruent. Messages are congruent if they are coherent, i.e. if all signals are compatible on all levels. One speaks of incongruent messages when speech and non-speech signals are contradicting one another. Following up on the examples mentioned above, news would be inconsistent if the person complaining about the heat came in with his coat collar turned up, the allegedly ashamed person looks at his counterpart boldly, the person expressing sympathy clearly keeps his distance or the person complaining about a lack of beer still has a few bottles standing next to him on the floor .

Remarks

- ↑ Often situations are meant in which relationships are disturbed. Schulz von Thun clarifies the relationship aspect in problematic situations in couples.

literature

- Friedemann Schulz von Thun : Talking to each other : disruptions and clarifications. Psychology of Interpersonal Communication . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1981, ISBN 3-499-17489-8 .

Web links

- The communication square on Friedemann Schulz von Thun's website

- Detailed explanation of the example "green in the soup"

- Detailed description of the four-sided model

Individual evidence

- ^ Paul Watzlawick, Janet H. Beavin, Don D. Jackson: Human Communication. Forms, disorders, paradoxes , Bern, Stuttgart, Toronto 1969, p. 53 ff.

- ^ Karl Bühler: Speech theory: the representation function of language , Stuttgart, New York 1982 (first edition 1934).

- ^ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, p. 13 ff.

- ↑ For the following see Friedemann Schulz von Thun: The anatomy of a message . In: Talking to each other. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, pp. 25-30.

- ^ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, p. 31.

- ^ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, p. 25.

- ^ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, p. 44 f.

- ^ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, p. 62 f.

- ^ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, p. 33 f.

- ^ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another. 1: Malfunctions and clarifications . Reinbek near Hamburg 1981, p. 35.