Raising Chicago

In the Raising of Chicago piecewise ground level was the center of Chicago increased by up to 2.5 meters. Streets, sidewalks and buildings were either built, physically lifted by lifting equipment, or moved. Elevation of the city began in 1856 and took about 20 years, with elevations ranging from less than a meter to nearly 2.5 meters (2-8 feet). There are no exact figures on the cost. However, estimates put it at $ 10 million or more, which would be anywhere between $ 245,630,000 and $ 310,480,000 today.

background

The city of Chicago rose an average of just five feet (1.5 meters) above Lake Michigan in the mid-19th century . Near the northern and southern branches of the Chicago River , the surface was between just under and over one meter (3–4 feet) above the level of the lake, while in western Chicago it was 3 to a maximum of 3.6 meters (10–12 feet) ) were. As a result, there was little or no natural runoff from the surface of the city for many years in the 19th century. The city stood on a swampy foundation, standing water fermented and created uncomfortable living conditions. Epidemics such as typhus and dysentery ravaged Chicago for six years in a row, culminating in a cholera outbreak in 1854 that killed more than 1,400 citizens. The sanitary conditions were blamed in no small measure for these fatal outbreaks.

The crisis forced the Aldermen (a municipal body) and city engineers to take the drainage problem seriously. On February 4, 1855, a law to set up a sewage commission was passed. The commission selected engineer Ellis S. Chesbrough for the job. In 1856 the city council passed a plan proposed by Chesbrough for the construction of a city-wide sewer system.

Parts of Chicago had to be raised to build the sewer system. Chesbrough proposed elevating the city approximately 3 meters (10 feet), the actual elevation being such as to allow the construction of 2.1 to 2.4 meters (7-8 feet) high basements. The approximately three meter elevation was discarded due to probable difficulties in obtaining soil for the backfill.

Beginning of raising

As a result, drains were laid, streets and sidewalks covered with several feet of earth and rebuilt. Vacant lots were replenished, some old timber frame houses demolished and the lots replenished, while other owners had their timber frame houses raised. The newer brick buildings posed a problem with displacement, they could not be raised. These buildings were left at the old floor level while streets and sidewalks were slowly raised. A city was formed, "built on two levels", with parts of the sewer system also running above the ground. Legal steps against the increase were unsuccessful. It was not until 1858 that brick buildings were raised.

Earliest raising of a brick building

In January 1858 the first masonry building was raised. It was a four story, 70 foot (21 meter) long, 750 ton brick building on the northeast corner of Randolph Street and Dearborn Street. It was raised to the new level on 200 lift spindles , which was 1.88 meters (6 feet 2 inches) above the old one. This happened "without the slightest damage to the building". It was the first of more than fifty brick buildings of comparable size to be raised this year. The contractor was Boston engineer James Brown, who entered into a business partnership with Chicago engineer James Hollingsworth. Before the year was over, they were lifting brick buildings that were more than 30 meters (100 feet) long. The following spring they signed a contract to lift a block of brick more than twice that length.

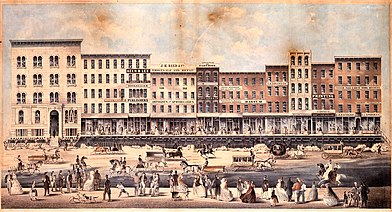

The row of streets on Lake Street

By 1860, confidence was enough for a consortium of six engineers, including Brown, Hollingsworth, and George Pullman , to lift one of the most significant areas of the city in one go. They were halfway up Lake Street, between Clark Street and LaSalle Street: a massive brick row of shops, offices, and printers. This project was 98 meters (320 feet) long, some four, some five stories high, with an area of 4.000 m 2 and an estimated total weight of 25,000-35,000 tons, including the hanging sidewalks. Shops that were located in these buildings were not closed during the uplift. As the buildings were raised, people came and went shopping and working in them like nothing special was going on. In five days, the entire assembly was raised four feet and eight inches (1.42 meters) higher with a group of six hundred men working with six thousand jacks. The spectacle attracted thousands of people, who on the last day were given permission to walk between the lifting equipment on the old floor level.

The Tremont House

The following year, a team led by Ely, Smith, and Pullman opened the Tremont House Hotel on the southeast corner of Lake Street and Dearborn Street. A brick building, six stories high and with a total area of more than 4,000 m 2 , which was luxuriously furnished. Again business continued uninterrupted while the hotel was lifted from the ground. Five hundred men worked with five thousand lifting devices in covered trenches. A regular was amazed that the entrance stairs to the hotel got steeper every day. The hotel, which until the previous year had been the tallest building in Chicago, was raised 6 feet (1.8 meters).

The Robbins Building

Another major feat was the elevation of the Robbins Building. This iron building was 150 feet (46 meters) long, 80 feet (24 meters) wide, five stories high, and was located on the corner of South Water Street and Wells Street. The building was very heavy, with an ornate iron frame, 305 mm (12 inch) thick wall, and heavy goods inside the building, it weighed an estimated 27,000 tons. Hollingsworth and Coughlin accepted the contract and in November 1865 not only was the building raised 0.70 meters (27.5 inches), but also 70 meters (230 feet) of the stone walkway outside the building.

Hydraulic lifting of Franklin House

There are reports that at least one building in Chicago, Franklin House on Franklin Street, was hydraulically raised by engineer John C. Lane . Lane's group had been using this technique in San Francisco since 1853 .

Moving Buildings

Many of the frame buildings hastily erected in downtown Chicago were now viewed as inadequate for the expanding and growing city. Instead of raising them, the owners often preferred to move these buildings to replace them with new brick buildings. Old, multi-story and intact wooden buildings, sometimes entire blocks of streets, were placed on rollers and moved to the outskirts of the city or to the suburbs. The traveler David Macrae described in disbelief: “Not a day went by during my stay in the city in which I did not come across one or more houses that were changing their quarters. I met nine in one day. Crossing Great Madison Street in horse-drawn carts, we had to stop twice to let houses pass. ”As with previous operations, stores stayed open even when customers had to climb through the moving front door.

See also

Web links

- Encyclopedia of Chicago: Street Grades, Raising

- Raising Chicago: An Illustrated History

- Episode 86 - Reversal of Fortune , radio broadcast

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Wolf, Garrett. A City and Its River: An Urban Political Ecology of the Loop and Bridgeport in Chicago. Diss. Louisiana State University, 2012, p. 61, Online ( October 19, 2013 memento in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Hill, Libby: The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History, Chicago 2000, p. 100

- ↑ Schultz, Stanley K., and Clay McShane. "To engineer the metropolis: sewers, sanitation, and city planning in late-nineteenth-century America." In: The Journal of American History 65.2 (1978): p. 393 ( online at JSTOR )

- ↑ a b Cain, Louis P .: "Raising and watering a city: Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough and Chicago's first sanitation system.", In: Technology and Culture 13.3 (1972): p. 362 ( online at JSTOR )

- ↑ Chicago Daily Tribune, January 29, 1857 ( Memento of May 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Soper, George A .; Watson, John D .; Martin, Arthur J .: A report to the Chicago real estate board on the disposal of the sewage and protection of the water supply of Chicago, Illinois (1915) , full text at archive.org , p. 69

- ^ Encyclopedia of Chicago: Epidemics , accessed September 5, 2013

- ↑ Chicago Daily Tribune, July 12, 1854 ( Memento of May 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Soper, George A .; Watson, John D .; Martin, Arthur J .: A report to the Chicago real estate board on the disposal of the sewage and protection of the water supply of Chicago, Illinois (1915) , full text at archive.org , p. 70

- ↑ a b Cain, Louis P .: "Raising and watering a city: Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough and Chicago's first sanitation system.", In: Technology and Culture 13.3 (1972): p. 361 ( online at JSTOR )

- ↑ "THE HOUSE RAISING ON RANDOLPH STREET." Chicago Daily Tribune (1847-1858): Jan. 26, 1858. ProQuest . Web: accessed on September 4, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "CITY IMPROVEMENTS IN 1858." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): Jan. 1, 1859. ProQuest . Web: accessed on September 4, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "TO BE RAISED TO GRADE." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): October 4, 1858. ProQuest . Web: accessed September 4, 2013, from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "CITY IMPROVEMENTS." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): May 5, 1859. ProQuest . Web: accessed September 4, 2013, from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ a b c "CITY IMPROVEMENTS." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): March 9, 1860. ProQuest . Web: accessed September 4, 2013, from ProQuest (requires access)

- ^ A b "The Great Building-Raising Contract." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): March 29, 1860. ProQuest . Web: accessed September 4, 2013, from ProQuest (requires access)

- ^ A b "The Great Building-Raising." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): April 2, 1860. ProQuest . Web: accessed September 4, 2013, from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "ON THE RISE." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): March 26, 1860. ProQuest . Web: accessed September 4, 2013, from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "THE TREMONT HOUSE IMPROVEMENT." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): January 22, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed September 4, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access) .

- ^ "The Tremont House Improvements." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): January 24, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "PROGRESSING." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): February 12, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "TREMONT HOUSE IMPROVEMENT." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): February 25, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "AT THE TREMONT." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): February 26, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "One, Two, Three, and up she Goes!" Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): February 26, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ^ "COMING UP" Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): February 27, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "THE TREMONT HOUSE IMPROVEMENT." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): March 15, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "The reopening of the Tremont House." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): July 26, 1861. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ a b David Macrae, The Americans at Home: Pen-and-Ink Sketches of American Men, Manners and Institutions, Volume 2, Edmonston & Douglas , Edinburgh 1870, pages 190-193, full text at Archive.org / full text at the University of Michigan

- ↑ "BLOCK RAISING." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): October 31, 1865. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "THE IRON BLOCK." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): November 14, 1865. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "THE IRON BLOCK!" Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): November 17, 1865. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "RAISING AN IRON BLOCK OF BUILDINGS." Chicago Tribune (1860–1872): November 20, 1865. ProQuest. Web: accessed on September 5, 2013 from ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ The Times (London), December 12, 1865 ( Memento of May 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ "Raising Building by Hydraulic Pressure - A Card." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): April 30, 1860. ProQuest. Web: September 4, 2013, at ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "RAISING BUILDING BY HYDRAULIC POWER." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): July 14, 1859. ProQuest. Web: September 4, 2013, at ProQuest (requires access)

- ^ David Young: Raising the Chicago streets out of the mud , accessed August 18

- ↑ "THE BRIGGS HOUSE." Chicago Daily Tribune (1858-1860): February 7, 1866. ProQuest. Web: September 4, 2013, at ProQuest (requires access)

- ^ "Local Department." Chicago Daily Tribune (1858-1860): April 18, 1856. ProQuest. Web: September 4, 2013, at ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "CITY IMPROVEMENTS — HOUSE MOVING." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): December 20, 1858. ProQuest. Web: September 4, 2013, at ProQuest (requires access)

- ↑ "CITY IMPROVEMENT." Chicago Press and Tribune (1858-1860): April 12, 1860. ProQuest. Web: September 4, 2013, at ProQuest (requires access)