Answering the question: What is Enlightenment?

Answering the question: What is Enlightenment? is an essay by the philosopher Immanuel Kant from the year 1784. In this article, published in the December issue of the Berlin monthly magazine , Immanuel Kant responded to Pastor Johann Friedrich Zöllner's question “What is Enlightenment?” published a year earlier in the same newspaper appeared. In this essay, Kant provided his classic definition of the Enlightenment .

background

In the December 1783 issue of the Berlinische monthly magazine , the Berlin pastor Johann Friedrich Zöllner published the article: Is it advisable not to further sanction the marriage union through religion? In a footnote, he asked the provocative question: “What is Enlightenment?” With the question, Zöllner alluded to the fact that there was still no clear definition of the movement, although it had existed for decades. This question from the Protestant pastor in Berlin, hidden in a footnote, was intended as a reply to the anonymous “E. v. K. ”signed and published article by the co-editor of the Berlin monthly journal Johann Erich Biester in September 1783, with the title , which was perceived as heretical, Proposal, that the clergy no longer endeavor to consummate marriages . This opened the so-called Enlightenment Debate, which proved to be extremely momentous and fruitful for the history of philosophy, especially in Prussia. In the September issue of the Berlin monthly magazine of 1784, the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn published an essay in response to the question: What does enlightenment mean? . Two months later, Immanuel Kant's essay was published in the December issue answering the question: What is Enlightenment? with the definition of enlightenment:

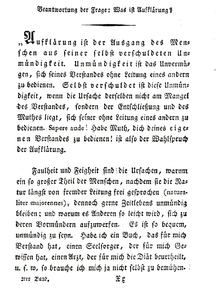

- Enlightenment is the exit of man from his self-inflicted immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one's mind without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-inflicted if the cause of it is not a lack of understanding but a lack of resolution and courage to use it without guidance from someone else. Sapere aude ! Have the courage to use your own reason! is the motto of the Enlightenment.

In a comment added later at the end, Kant writes that he was not yet familiar with the essay by Moses Mendelssohn and that he would otherwise have withheld his.

The essay in detail

Kant begins his essay immediately with a definition. According to him, enlightenment is the “exit of man from his self-inflicted immaturity.” These terms are explained in the following two sentences. Immaturity is the "inability to use one's mind without the guidance of another". This immaturity is self-inflicted if its reason is not a lack of understanding but the fear of using one's own understanding without the guidance of another. Then Kant inserts the Enlightenment motto: "Sapere aude!", Which means, for example, "Dare to know!" And is explained by Kant with "Have the courage to use your own understanding!" Later Kant also provided a simpler definition of the Enlightenment elsewhere: "[T] he maxim to think for yourself at all times is the Enlightenment ."

In the following paragraph, Kant explains why a large proportion of people, although they have long since grown up and would be able to think for themselves, remain immature throughout their lives and still like to be. The reason for this is "laziness and cowardice". Because it is easy to be a minor. The "annoying business" of independent thinking can easily be transferred to others. If you have a doctor you don't have to judge your diet yourself; instead of acquiring knowledge for oneself, one could simply buy books; those who can afford a “pastor” do not need a conscience themselves. So it is not necessary to think for yourself, and the majority of people (including the "entire fair sex") make use of this possibility. This makes it easy for others to become the “guardians” of these people. These guardians also ensured that the “underage” people “considered the step to maturity” to be not only difficult but also dangerous. Kant here drastically compares the unenlightened people with "domestic animals" that have been made stupid. They would be locked in a “ goat cart ”, which was a basket frame on wheels in the 18th century that children used to learn to walk. These “imprisoned people” were always shown by their guardians the dangers that threatened them if they tried to act independently. So it becomes difficult for every single person to free himself from immaturity on his own - on the one hand because he has "grown to love" it, because it is comfortable, and on the other hand because he is now for the most part really incapable of understanding his own understanding because he was never allowed to try and he was deterred.

Kant then deals with the enlightenment of the individual in comparison to the general public. Because of the conditions described above, the individual person has only limited opportunities to enlighten himself. It is more likely that an “audience” will enlighten itself, that is, in contrast to the individual, the entire society of a state or large parts of it. Because among the large number of underage citizens there is always a few “self-thinking”. Kant demands freedom as a precondition . Under these conditions, it seems to him that the public is “almost inevitable”. Kant rejects this through a revolution. A revolution will never enable a “true reform of the way of thinking”. So he relies on reform instead of revolution.

The freedom demanded by Kant as a necessary prerequisite for the Enlightenment is the right to “make public use” of one's reason in all areas. The public use of reason is that which someone makes as a private person, e.g. B. as a scholar in front of his reading audience. In contrast to this is the "private use" of reason. This is the use of reason that someone makes as the holder of a public office, e.g. B. as an officer or as a civil servant. The public use of reason thus includes freedom of speech , the right to freedom of expression in speech and writing. According to Kant, he must “be free at all times”. On the other hand, the private use of reason can (and must partly) be “often very narrowly restricted”. This is no longer a hindrance to clarification. Kant gives the following example to explain this: When an officer in the military service receives an order from his superiors, he should not argue about the expediency or usefulness of this order while on duty, but must obey. However, he could not be prevented later from writing about the mistakes in military service and then presenting this to his reading audience for evaluation.

Officials, but also the individual citizens, are accordingly in the area of their office or their civic duties, e.g. B. when paying taxes, to obedience in order to guarantee the order and security of the state and its institutions. But because scholars can make public use of their reason, there is the possibility of a public scientific discussion of the conditions in the state. In this way the monarch can be moved to understand and change the situation. Thus, according to Kant, reforms can be achieved.

The question “Are we now living in an enlightened age?” Says no, but one is now living in an enlightened age. In "religious matters" in particular, most people are still very far from using their own minds without outside guidance. However, there are also clear signs that general education is making progress.

Quote

- "That the vast majority of people (including the whole fair sex) consider the step to maturity, apart from the fact that it is difficult, also very dangerous: those guardians who have kindly taken over the supervision of them take care of that . “- Immanuel Kant

literature

- Immanuel Kant: Answering the question: what is enlightenment? In: Berlinische Monatsschrift, 1784, no. 12, pp. 481–494. ( Digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Ehrhard Bahr (Ed.): What is Enlightenment? Theses and definitions. Kant, Erhard, Hamann, Herder, Lessing, Mendelssohn, Riem, Schiller, Wieland. ISBN 3-15-009714-2 .

- Otfried Höffe : Immanuel Kant . 6th revised edition. Publishing house CH Beck, Munich 2004.

- Immanuel Kant: What is Enlightenment? Selected small fonts. In: Horst D. Brandt (Ed.): Philosophical Library (Vol. 512). Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-7873-1357-5 .

Web links

- Text after the academy edition

- Text as audio text (YouTube)

- Hans-Martin Gerlach : Kant and the Berlin Enlightenment , session reports of the Leibniz Society 69 (2004), 55–64

- Gerhard Schwarz: Kant's idea of education as an enlightenment of the human being to his divinity , published in: Ian Kaplow (Hrsg.): After Kant: inheritance and criticism. Lit, Münster 2005, 84-88.

Remarks

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Zöllner: Is it advisable not to further sanciren the marriage covenant through religion? In: Berlinische Monatsschrift 2 (1783), pp. 508–516, here p. 516, note: “What is Enlightenment? This question, which is almost as important as: what is truth, should be answered before you begin to enlighten! And yet I have not found the answer anywhere! "

- ↑ Johann Erich Biester: Proposal not to trouble the clergy any more in the execution of marriages. In: Berlinische Monatsschrift 2 (1783), pp. 265–276.

- ↑ Moses Mendelssohn: On the question: what does enlightenment mean? In: Berlinische Monatsschrift 4 (1784), pp. 193-200.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: Answering the question: What is Enlightenment? In: Berlinische Monatsschrift 4 (1784), pp. 481–494.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: What does it mean to orient oneself in thinking? , AA VIII, p. 146.