Collins Line

The Collins Line was an American shipping company founded in 1847 by businessman Edward Knight Collins, which operated the transatlantic route between ports on the American east coast and Great Britain. It was created as a counterweight to the British shipping company Samuel Cunards , who had had a monopoly on regular services between the two continents since 1840. For this reason, Collins' ships were heavily subsidized by the state .

Despite operating some of the largest and fastest ships of the time, the Collins Line was never economically profitable. In addition, several of their ships were lost in accidents involving losses. The shipping company had to file for bankruptcy as early as 1858. Despite its financial failure, the Collins Line plays an important role in the history of transatlantic shipping due to its increased competition on the North Atlantic route and numerous technical innovations, in particular the comfort of the ships.

history

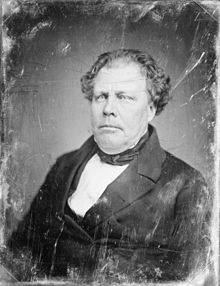

Edward Collins (1802–1878) had already maintained a first shipping line for the postal service on the US east coast in the 1830s. This shipping company - Dramatic Line - maintained numerous smaller sailing ships and proved to be a financial success. With the regular transatlantic liner service by the British Cunard Line since 1840, the need to participate in this profitable business grew in the USA. In addition, there was fear of suffering a loss of reputation due to Cunard's monopoly. Collins then succeeded in fueling the public debate and making himself heard by the highest authorities: In 1847 he founded his new transatlantic shipping company under the name Collins Line and undertook to offer 20 crossings per year between the USA and Great Britain and to carry mail. The US Congress approved annual subsidies amounting to an enormous 385,000 US dollars. How sharp the debate about participation in the Atlantic Service was, shows the statement of Congressman Edson Olds: "We have the fastest horses, the most beautiful women and the best rifles in the world, and we must also have the fastest steamers!"

Collins maintained a total of five ships, four of which were more or less identical (year of completion in brackets): Atlantic (1849), Pacific (1849), Baltic (1850) and Arctic (1850). They were around 2,850 GRT and reached top speeds of around 13.5 knots. A fifth, the significantly larger Adriatic (3,650 GRT, 15 knots), only joined the fleet in 1857. The sailing steamers were built in the shipyards of William Brown and Jacob Bell in New York .

The competition for the highest possible speed was initially successful: Collins' ships crossed the North Atlantic faster than their competitors on the Cunard Line, initially the Baltic won the Blue Ribbon in 1850 , then the Arctic trumped its sister ship in 1852 . With an average speed of around 13 knots and a travel time between New York and Liverpool of just under 10 days, the ships were the fastest steamers of the time.

However, the massive utilization of the machinery and boiler systems due to the high speed of travel quickly led to expensive shipyard stays, and fuel costs rose alarmingly. In 1852, the US government increased its grants to $ 858,000, but even that amount could only offset part of the losses Collins incurred - in the same year they were around $ 1.7 million.

In 1854 one of the most serious catastrophes in US civil shipping occurred, which severely damaged Collins' reputation: The Arctic was rammed by a smaller steamer in the thick fog off Newfoundland and so badly damaged that it sank after a few hours. 322 people were killed on it, including Collins' wife and two of his children; a personal loss that the shipowner should never get over. In 1856 the Pacific disappeared without a trace on a crossing from Liverpool to New York with 186 people on board, her whereabouts have not yet been clarified beyond doubt.

After these severe blows, the shipping company's already inadequate sales quickly fell even further. In 1857, Congress cut the grants to the originally set amount of $ 358,000, which was totally inadequate in view of the shipping company's situation. Collins still managed to complete his largest ship, the Adriatic , but after her second crossing he had to file for bankruptcy. The relics of his fleet were sold to a freight line for the small sum of US $ 50,000 and converted into pure sailing ships.

Technical achievements

Collins' ships set new standards not only in terms of cruising speed, but also and above all in terms of travel comfort. The Spartan equipment of Cunard ships should be trumped by a magnificent design of public spaces and cabins: The Collins Steamer offered stucco lounges with steam heating , gilded carvings and precious fabrics and antique furniture . The generous use of wall mirrors should optically hide the cramped conditions of the ocean liners of the time. The cuisine on board was excellent, rich meals with exquisite dishes were standard in society. In order to be able to offer the freshest possible ingredients, the steamers even had their own ice cellar to keep perishable goods fresh on the two-week sea voyage across the Atlantic. As a special novelty, Collins also offered an on-board hairdresser on his ships. The marine engines that drove the paddle wheels were among the most powerful of their kind and achieved an output of up to 3,000 hp. However, the basic design of the ships - especially in connection with the high speed - was downright dangerously conservative: The hulls of Collins' sailing steamers were almost entirely made of wood, which had two negative effects: On the one hand, they were significantly more sensitive to collisions or grounding than the iron structures already in use at that time (which had devastating consequences when the Arctic collided with a smaller but iron-built ship), and on the other hand, the hulls wore out much faster at the high speeds they had run and had to be overhauled.

Despite his failure, Collins' merit lies in the fact that the purely purpose-built passenger ship, which its passengers had viewed more or less as a "cargo", was turned into an aesthetically pleasing and comfortable floating hotel. This undoubtedly represents an essential step on the way of the transatlantic liners to the modern luxury ship.

It was only after the First World War that the USA began to participate in transatlantic passenger traffic on a larger scale. The 1952 United States was the first attempt to build another record ship in terms of size and speed.

literature

- Maddocks, Melvin: The Big Passenger Ships. Eltville am Rhein, 1992.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Maddocks, Melvin: The Great Passenger Ships. Eltville am Rhein, 1992, p. 28.