Conatus

Conatus ( Latin cōnātus (from the verb cōnāri) for effort, endeavor, striving ) is a philosophical term that describes the inner tendency of a thing to continue to exist at all or with regard to a specific property (persistence, self-preservation) or to become larger. Conatus can refer to mental or material objects, such as the instinctive "desire to live" or different types of movement and indolence . Physical and more general uses are often difficult to distinguish.

Antiquity

The term has been used in philosophical psychology , metaphysics, and physics since ancient times ; the Latin expression already has Greek equivalents. In particular, the expression ὁρμή (hormê, Latin mostly translated as impetus ) is used here, especially among stoics and peripatetics . This describes the movement of the soul in the direction of an object as the cause of an action.

Both Aristotle, and later Marcus Tullius Cicero and Diogenes Laertius, suggested a bond between the conatus and other feelings, with the former introducing the latter in their opinion. For example, they claimed that people do not want to do something because they think it is "good", rather they think something is "good" because they want to do it, in other words, the reason for human aspiration is a natural inclination of the body to fulfill its desires in accordance with the principles of the conatus .

Cicero and Laertios also refer to the striving for self-preservation in non-human individuals as conatus .

middle Ages

Johannes Philoponus criticizes the Aristotelian concept of movement, particularly starting with the analysis of projectile movements; He does not take any causal effectiveness of surrounding parts of space as a basis, but rather a tendency to movement in the body itself - which he calls conatus. In contrast to the modern concept of inertia , an "inherent force" is assumed. (see on this and on the following also the history of physics )

The Arabic philosophers use the term i'timād , for example , in a sense that is often very similar to the Latin conatus ; for example some Mu'tazilites and Avicenna when analyzing the tendency of material bodies to fall down. Averroes and others defend the classical Aristotelian conception against John Philoponus. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), however, defends the latter and develops a concept that comes close to the modern concept of inertia; his contemporary Avicenna used a term that comes close to the modern ( Newtonian ) concept of impulse : there is proportionality to the product of mass and speed.

Thomas Aquinas , Duns Scotus , Dante Alighieri and others use conatus synonymously with velle, vult (voluntas), appetitus and their derivatives, which is also associated with a restriction to animated animals. Like Abravanel , Thomas connects the concept of Conatus with the Augustinian concept of natural movement or natural persistence in an intermediate position, which is known as "amor naturalis" (natural affection).

Johannes Buridanus developed a concept of impetus that comes close to the modern concept of impulse and includes, for example, non-linear movements (especially circular movements), but still adheres to many components of Aristotelian natural philosophy, such as the thesis of a fundamental difference between stationary and moving objects.

Modern times

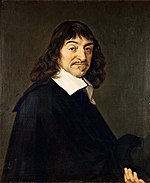

In the first half of the 17th century René Descartes developed his interpretation of the conatus , which he describes as the "acting force or tendency to move, of bodies that reflects the power of God". This moves away from the use of words in the context of human endeavors and also from the medieval use of conatus as an internal property of things. For Descartes, in contrast to Buridan, motion and the state of rest are two states of the same thing, not two different ones.

The Conatus theories of other important philosophers of the early modern period, such as Spinoza , Gottfried Leibniz and Thomas Hobbes , are also particularly well known . In the context of a theory, often referred to as pantheistic , such as that outlined by Spinoza, the Conatus concept can be connected with the divine will. Especially in dualistic framework theories such as those developed by Descartes, a distinction can be made between psychological and material aspects of the Conatus concept, also when applied to movement processes. Leibniz understands the will as inclination or striving (conatus) away from what is considered bad and towards what is considered good. Around 1600, Bernardino Telesio and Tommaso Campanella also ascribed a conatus to inanimate objects .

Theorists of the 19th and 20th centuries are still influenced by this tradition of the Conatus term. Today the term conatus is no longer used in physics and technology. Instead, partial aspects of what is meant by this are captured using terms such as inertia or conservation of momentum.

Others

The contemporary composer Rainer Kunad did not give his works the usual opus numbers, but rather gave most of his compositions a conatum number.

literature

- Roger Ariew: Historical dictionary of Descartes and Cartesian philosophy , Lanham, Md .; Oxford: Scarecrow Press 2003.

- Richard Arthur: Space and relativity in Newton and Leibniz , The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 45/1 (1994), 219-240.

- Howard R. Bernstein: Conatus, Hobbes, and the Young Leibniz . Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 11 (1980), 167-81.

- Laurent Bove: L'affirmation absolue d'une existence essai sur la stratégie du conatus Spinoziste , Université de Lille III: Lille 1992.

- Lawrence Carlin: Leibniz on Conatus, Causation, and Freedom , Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 85/4 (2004), 365-379.

- Jacques Chamberland / Francois Duchesneau (eds.): Les conatus chez Thomas Hobbes , The Review of Metaphysics (Université de Montreal) 54/1 (2000)

- D. Garret / Olli Koistinen / John Biro (eds.): Spinoza's Conatus Argument , Spinoza: Metaphysical Themes 1, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2002, 127

- Juhani Pietarinen: Hobbes, Conatus and the Prisoner's Dilemma

- A. Sayili: Ibn Sīnā and Buridan on the Motion of the Projectile , Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500/1 (1987), 477.

- M. Schrijvers / Yirmiyahu Yovel (eds.): The Conatus and the Mutual Relationship Between Active and Passive Affects in Spinoza . Desire and Affect: Spinoza as Psychologist, New York: Little Room Press 1999

- Richard Sorabji : Matter, Space, and Motion: Theories in Antiquity and their Sequel , London: Duckworth 1988.

- Diane Steinberg: Belief, Affirmation, and the Doctrine of Conatus in Spinoza , Southern Journal of Philosophy 43/1 (2005), 147-158.

- Rich Wendell: Spinoza's Conatus doctrine: existence, being, and suicide , Waltham, Mass. 1997

- A. Youpa: Spinozistic Self-Preservation , The Southern Journal of Philosophy 41/3 (2003), 477-490.

Web links

- Rudolf Eisler : Art. Striving , in: Dictionary of philosophical terms, 1904.

Individual evidence

- ↑ s. Guy Monnot: Penseurs musulmans et religions iraniennes, Vrin 1974, ISBN 2-7116-0575-2 , 37-39

- ↑ Nouveaux Essays II, cap. 21, § 5

- ^ Preliminary list of the estate in the SLUB Dresden