Curator rei publicae

The curator rei publicae (crp, literally “the one who cares for the common good”, also curator civitatis , in German sometimes “city curator ”) was an extraordinary official in the Roman Empire . He was appointed by the emperor to ensure orderly conditions in a city, especially in the municipal finances. Later, the temporary, irregular, rare office changed into the regular supreme office of a Roman city .

swell

The sources about the crp are initially epigraphic , usually grave and honorary inscriptions. These usually reflect the official career paths of the person concerned, although the assignment of someone designated as a curator or a cura agent is not always very clear. It is similar with the legal sources (legal commentaries or legal collections) in which a curator occurs.

Ancient jurists who wrote about the activity of a crp included Ulpian and Papirius Iustus , who wrote before Severus (i.e., AD 306). With him, the crp was a special representative in addition to the regular magistrates.

appointment

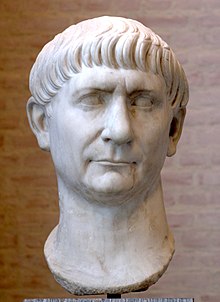

At first, crp appears to have been installed in the time of the Emperor Trajan , who ruled from AD 98 to AD 117. In the course of the 2nd century the number of office holders increased, at least according to the epigraphic sources. There are examples of crp from the senatorial, but also from the knight class. Usually, but not always, the crp did not come from the municipality in which it was used, but it often came from the same region.

A cura (care) was initially just a public task, as there were in large numbers in ancient communities, such as the cura aquae or cura pecuniae publicae . Usually the city magistrates assigned a person with a cura . All of these offices were honorary, the official was liable. They were only exercised by high-ranking, wealthy personalities who could afford unpaid work. That is why it was not always easy to find such people for a cura .

In the older ancient scholarship, the crp was seen rather negatively as an instrument with which the emperor wanted to intervene in the autonomy of the cities. Later, when more inscriptions became known, the picture changed. The number of officials and the cities affected was small; there can be no question of comprehensive surveillance of all cities.

Since many CRPs received a dedication (a mark of honor) from the churches in which they served, it is likely that the appointment of such a curator was not always against the will of the church. Rather, it was often the congregation itself, or some of the local officials, who asked for the posting. The lack of knowledge of the local officials about the complicated financial system, as well as nepotism and corruption, led to a misery that forced the emperor to intervene, according to Walter Langhammer. The establishment of a crp, however, did not contribute to the independence of the community and increased the lack of independence in a vicious circle.

tasks

The curator received a letter of assignment from the emperor with very precisely defined and limited tasks; his activity was limited in time and tailored to the city concerned. A CRP did not necessarily reside in the city. He also did not take over the function of the actual administration, the regular officials of the city continued to work. However, the authority of the emperor gave him a great deal of power.

As a rule, the task was to organize the community finances, above all to check whether everything was going well with property purchases and public buildings. According to Burton, the Roman governor of a province actually had extensive powers to control parishes, but was limited by a lack of time and resources. A crp, on the other hand, did not have to deal with jurisdiction or tax collection, but could concentrate on municipal finances and administration. In this narrow sense, Burton said, the crp could be seen as a kind of additional provincial governor.

Change to the regular senior civil servant of the city

The crp gradually became a normal function in a Roman city. In the middle of the 3rd century, the crp began to exercise powers of the local officials themselves. Burton refers to the well-known example of a crp who participated in the persecution of Christians in North Africa at the beginning of the 4th century. His actions corresponded to what was normally the responsibility of local magistrates. Burton suspects that the transition to a regular office was to be located in the late 3rd century, as a result or even conscious measure of the reforms of the tetrarchy .

Since Constantine the crp served as "the vicar of the governor in the community". Langhammer writes that they were elected by the ordo decurionis of the community and confirmed by the emperor. They were responsible for the finances and administration of the community as a whole, and they corresponded with the emperor and the governor. In the event of differences of opinion, the communities could appeal to the emperor.

numbers

The tradition is incomplete. Nevertheless, given the many cities that existed at that time and the long periods of time, one can assume that most cities never had a crp as the Emperor's special envoy. From Italy up to and including the 3rd century 251 crp are known. 139 were senators, 83 knights (29 without information). Six ministers have come down to us in Italy for the time of Trajan and 46 for the time of Severus and Caracalla.

In North Africa , from 196 AD, when a crp was first mentioned there, until 282 there was only 18 crp known today. For the province of Asia (about the west of today's Turkey), thirty crp have been handed down for the hundred years up to 260 AD.

See also

literature

- GP Burton: The Curator Rei Publicae. Towards a Reappraisal. In: Chiron Vol. 9, 1979, pp. 465-487.

- Ernst Kornemann : Curatores . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IV, 2, Stuttgart 1901, Sp. 1774-1813.

supporting documents

- ↑ Werner Eck: The state organization of Italy in the high imperial era , CH Beck, Munich 1979, p. 218.

- ^ Werner Eck: The state organization of Italy in the high imperial era , CH Beck, Munich 1979, p. 219, p. 222.

- ^ After GP Burton: The Curator Rei Publicae. Towards a reapprisal . In: Chiron , Vol. 9, 1979, pp. 465-487, here pp. 479/480.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The state organization of Italy in the high imperial era , CH Beck, Munich 1979, p. 211.

- ↑ Walter Langhammer: The legal and social position of the Magistratus Municipalis and the Decuriones in the transition phase of the cities from self-governing communities to executive organs of the late antique coercive state (1st-4th century of the Roman Empire) . Steiner, Wiesbaden 1973, p. 169.

- ^ GP Burton: The Curator Rei Publicae. Towards a reapprisal . In: Chiron , Vol. 9, 1979, pp. 465-487, here pp. 476/477.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The state organization of Italy in the high imperial era , CH Beck, Munich 1979, p. 227.

- ^ GP Burton: The Curator Rei Publicae. Towards a reapprisal . In: Chiron , Vol. 9, 1979, pp. 465-487, here p. 477.

- ^ GP Burton: The Curator Rei Publicae. Towards a reapprisal . In: Chiron , Vol. 9, 1979, pp. 465-487, here pp. 480/481.

- ↑ Walter Langhammer: The legal and social position of the Magistratus Municipalis and the Decuriones in the transition phase of the cities from self-governing communities to executive organs of the late antique coercive state (1st-4th century of the Roman Empire) . Steiner, Wiesbaden 1973, p. 169, p. 175.

- ^ GP Burton: The Curator Rei Publicae. Towards a reapprisal . In: Chiron , Vol. 9, 1979, pp. 465-487, here p. 481.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The state organization of Italy in the high imperial era , CH Beck, Munich 1979, p. 211.

- ^ GP Burton: The Curator Rei Publicae. Towards a reapprisal . In: Chiron , Vol. 9, 1979, pp. 465-487, here pp. 481-483.