The Horla

The Horla (French Le Horla ) is a short story by Guy de Maupassant . The first version appeared on October 26, 1886 in Le Gil Blas . The final version was published in 1887 in the book edition Le Horla published by Paul Ollendorff, Paris .

action

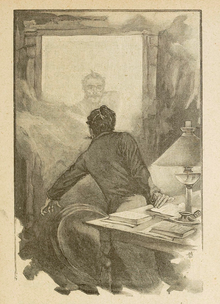

The novella in the final version is structured like a diary and describes the health deterioration of the narrator. In the first version, the narrator describes his experiences as a patient to several doctors in a psychiatric clinic. The protagonist realizes that an invisible being controls his will with hypnotic powers and sucks his life force out of his sleep. Since the being drinks water, he places a water carafe on his bedside table in the evening and then smears his hands with graphite , which, if he drank the water himself at night, would have to leave traces. The next morning the carafe is empty and shows no traces of graphite. The narrator escapes to Paris, where he takes part in an evening party, during which a hypnotist appears and orders a participant in a trance to ask the narrator for money the next morning. She actually does so and cannot remember what happened afterwards. The narrator returns to his country house and initially notices any paranormal events. But then Horla gains power over him. The narrator perceives the physical presence of the Horla. Once he observes how the pages of a book seem to turn over on their own, once he doesn't see his image in the mirror because Horla is obviously standing in front of him. Here the first version ends with the fear that a being superior to humans has come to take over world power.

In the second version, the narrator has his bedroom equipped with a security door and window bars. When he is sure that Horla is in the room, he locks him up and burns his house down. The servants he forgot die in the attic. However, the narrator is not sure whether Horla died in the fire and fears that the last resort to escape from him would be suicide.

Form and style of speech

The form of the narrative in the first version is that the first-person narrator describes his drama to a number of doctors. The doctor's final report, in which he cannot judge whether the patient is crazy or he, the doctor himself, gives the story a special note of insolubility.

The story is characterized by Maupassant's powerful language. He transcribes the breathless rush and great anguish of the first-person narrator into a short of breath staccato style. He depicts hopelessness and self-doubt with a myriad of questions and exclamations. The triumph of the first-person narrator at the end is presented in a spontaneous speaking style and word repetitions. In the course of the action, sentences are crippled and are intended to document the galloping madness.

Position in literary history

Classification in the work of the author

Horla was created in Maupassant's second creative phase after the great success of Bel-Ami's novel in 1885 and the less depressive phase in the mid-1880s. The Horla is one of Maupassant's few fantastic stories. The work attracted great attention when it was published. It is known that Maupassant was fascinated by the borders of consciousness and pathological states. At the time of writing, however, there were no signs of madness in the author himself. Since 1880 he suffered repeatedly from hallucinations, but was still largely certain of his creative power while writing the Horla.

Position in literary history

The novella is still one of the primary fantastic stories in world literature, ranked alongside stories by Marcel Proust .

Work analysis and reception

The Horla can be seen as the prototype of Maupassant's fantastic novels . All possible manifestations of madness, fear and hallucination are shown here. The end represents the hero's psychological decline. Horla is the diary report of a man whose physical and mental condition is steadily worsening. With his analytical mind he searches for the causes of the suffering. He cannot analyze his case with his senses; the malaise is imperceptible. It is beyond human knowledge. Nevertheless, the first-person narrator blames the reasons for his miserable state on his senses, precisely because they cannot help him. However, the senses cannot grasp and penetrate the whole of reality. The invisible becomes more and more of an obsession as the story progresses. The narrator never stops thinking. The analysis of perception becomes more important than perception itself. The restriction of perception and knowledge leads to the disintegration of the autonomous will and the collapse of the autonomous personality: "I can no longer want, but someone wants for me and I obey."

Rationality dominates the world of emotions. It develops terrorist domination over the narrator, who always tries tensely to have his insides “under control”. Like the outside, the inside should also be made visible. The narrator makes it clear that his inner emptiness is filled by a mysterious other being, the Horla (hors-là = out there), who only exists in his imagination and destroys him as an illusory force. Being alone torments him. His partner is the diary. In writing, the fear of being alone increases.

Rationality cannot help solve the problem. The rational attempt at a conclusion by the reader, to stamp the narrator as mentally ill and to recognize the individual, the father or the mother as the cause, falls short and is against Maupassant's intention. Rationality and madness are too closely linked. The problem remains unsolved.

Perception can be seen as the central theme of the narrative. The fact that the narrator wants to recognize his problems with perception shows an enormous constriction of reality. The senses are reduced to their reality-mastering function. They are de-subjectified, scientified and thus degraded to mere tools of work and knowledge. True sensuality is mutilated. Sensual relation to existence is lost. The subject objectifies.

"The reader is almost imperceptibly drawn into the maelstrom of identification with the first-person narrator and experiences the destruction of an initially intact personality, accompanied by increasing horror, in a confusing and dismaying directness that is hardly unparalleled in other novels."

The 1963 horror film Diary of a Madman , directed by Reginald Le Borg , is based on Maupassant's novella.

Others

Guy de Maupassant called his captive balloon Horla . He describes an excursion with this in the story The Flight of Horla , which is not related to the Horla novella.

Adaptations

- Patrice Oliva : Der Horla (Chamber Opera, Premiere November 2018)

expenditure

- Le Horla . In: Guy de Maupassant: Contes et nouvelles. Tome 2. Texts établi et annoté by Louis Forestier. Pp. 1612-1625. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. Ed. Gallimard 1979.

- Critical edition with both versions.

- The jewelery. The devil. The Horla . Trans. U. ed. by Ernst Sander . Stuttgart, Reclam, ISBN 978-315-006795-6

- The Horla. Audio book. Festa-Verl. 2004. Ed. U. Speaker HR Giger, ISBN 3-8-6552003-0

literature

- Ulrich Döring. Perception and sensuality in the fantastic literature of France in the 18th and 19th centuries. Inside: Guy de Maupassant: “Le Horla” (1887) The realm of the invisible. Pp. 297-360. Philosophical dissertation at the University of Tübingen. Altendorf 1984.

Web links

- Guy de Maupassant: The Horla in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Full text based on the translation by Georg Freiherrn von Ompteda

- Detailed table of contents

- Guy de Maupassant, Der Horla , reading on youTube

- Guy de Maupassant, The Horla , reading on Librivox

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Hermann Lindner: Afterword in Guy de Maupassant: From love and other wars. Novellas. Newly translated by Martin Lindner. dtv 2014, ISBN 978-3-423-14316-5

- ↑ a b Ernst Kemmer. Epilogue to: Guy de Maupassant. Six contes . Reclam foreign language texts. 1997. ISBN 978-3-15-009037-4

- ↑ student, Gerda. Guy de Maupassant in: Lange, Wolf-Dieter (eds). 19th Century French Literature III. Naturalism and symbolism. UTB 1980. pp. 236-253

- ↑ a b c d Ulrich Döring. Perception and sensuality in the fantastic literature of France in the 18th and 19th centuries. Inside: Guy de Maupassant: “Le Horla” (1887) The realm of the invisible. Pp. 297-360. Philosophical dissertation at the University of Tübingen. Altendorf 1984.

- ↑ Blüher, Karl Alfred. Maupassant, Sur l'eau, La parure, Le Gueux in: The French Novella. Edited by W. Kröhmer. Düsseldorf 1976

- ^ Diary of a madman on omovie , accessed September 19, 2015.