The immortal Golowan

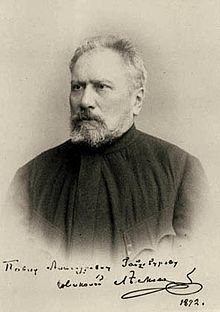

The immortal Golowan ( Russian: Несмертельный Голован , Nesmertelny Golowan ) is a story by the Russian writer Nikolai Leskow , which appeared in 1880 in issue 12 of the magazine Historischer Bote .

Golowan is a righteous man. The term righteous in Leskow means a fair Russian who helps the people in an emergency and whom they blindly trust.

content

The legend of Golowan

Leskov tells of his early childhood in Oryol . When Nikoluschka (Leskov's nickname) is attacked by a rabid chain dog, the smiling Golowan - a muscular giant in greasy sheep's clothing - is there to save the toddler's life.

The farmer Golowan, ransomed by General Jermolow , had gradually made himself independent as a farmer on the Orlik steep bank. From the income from his dairy farm , Golowan had first ransomed his mother and then his three older sisters from serfdom . The Molokane - as Golowan was called in Oryol - had still taken Pawla, a very hardworking, friendly woman. Golowan loved Pawla. People called this wife of the infamous rider Ferapont Golowan's Sin . Ferapont had deserted from the mounted Moscow fire brigade and abandoned his shy wife.

Golowan's mother died. Immortal Golowan called awesome in Oryol since he fearlessly into the homes of plague had gone sick and this was maintained without themselves on the disease cancer. The plague really couldn't harm Golowan because he was protected by the bezoar stone that the pharmacist had lost. Golovan had stopped the plague in Oryol with an offering to the river god. He had cut off his left calf with a scythe blade, threw it into the Orlik and fell over. Golowan had survived and has been hopping while walking ever since.

Many other miracles have been attributed to Golowan. He had been seen walking over the Orlik, leaning on a stick. In early summer he heard people trying to build a well how the water flowed underground.

Whenever an Oryol merchant ate the needy, Golowan usually took over the distribution of the gifts because he knew every native better. Once he was introduced to a stranger at such a meal: Fotej, the healed man, had been cured by a saint. To the astonishment of the Oryoles, Fotej did not thank Golowan for the mild gifts, but slapped him in the face. Golowan accepted that.

Grandmother's truths

Of course, Golowan was mortal: during the great fire in Oryol, Golowan wanted to help extinguish the fire, stepped into a waste pit covered with fly ash and was "boiled" in it.

As an adult, Leskov visits his grandmother in Oryol not long before her death and asks her about Golowan. The grandmother was the right address, because that was the case during Golowan's lifetime in Oryol: some residents mistrusted the clerk and preferred to go to a man he trusted - Golowan wrote contractual matters in a copybook. It burned with the fire mentioned above, but Golowan often consulted with Leskov's grandmother about such facts that were worth writing down. In addition, Golowan must have shared personal information with the grandmother during these discussions. So she can answer the grandson's questions: Golowan had removed a plague boil on his calf with the emergency operation mentioned above and Fotej, the healed man, was none other than the deserter Ferapont. Golowan's sin was not a sin . Golowan's love for the married woman Pawla was purely platonic, precisely because Golowan had been a righteous man.

reception

- According to Rudolf Marx (1968), Golowan is "a simple farmer who is the only one who is free from his instincts and who lives and sacrifices himself among all unfree people, tormented by misery and superstition".

- Reissner wrote in 1971: “Golowan only recognizes the authority of God and unconditionally follows his conscience oriented towards it. He takes the commandment of Christian charity, goodness and forgiveness seriously and prefers to forego his own happiness rather than inflicting suffering on someone else. "Then Reissner then goes into the mixed form of legend / novella: Once the legend of an immortal is built. On the other hand, there are memories of Leskov's old homeland (the place of the action), through which reality is brought in.

literature

German-language editions

- The immortal Golowan. German by Ena von Baer . P. 196–260 in Nikolai S. Leskow: At the end of the world and other master stories. 391 pages. Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1968 (2nd edition)

- The immortal Golowan. From the tales of the three righteous. German by Günter Dalitz. P. 65–123 in Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. The juggler pamphalon. 616 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1971 (1st edition)

- The immortal Golowan. Translated from the Russian by Günter Dalitz. P. 5–59 in: Nikolai Leskow: Das Schreckgespenst. Stories. With book decorations by Heinrich Vogeler . 272 pages. Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag, Leipzig and Weimar 1982 (1st edition, series: Die Bücherkiepe )

Output used:

- The immortal Golowan. German by Günter Dalitz . P. 483-539 in Eberhard Dieckmann (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. 4. The unbaptized priest. Stories. With a comment from the editor. 728 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1984 (1st edition)

Secondary literature

- Eberhard Reissner (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. The enchanted pilgrim. 771 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1969 (1st edition)

Web links

- The text

- online in the Gutenberg-DE project , Musarion Verlag, Munich 1923, translator: Alexander Eliasberg

- online at Lib.ru / Classic (Russian)

- online at RVB.ru (Russian)

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

- Entries in WorldCat

Remarks

- ↑ Golowan - russ: Großkopf (Reissner, 1969 edition, p. 760, footnote 178).

- ↑ Leskov poses as the narrator because he uses the names of his parents and his father's occupation in Oryol. In addition, the date of May 26, 1835 in the context roughly matches Leskov's life data (edition used, p. 484, 16 th Zvu and p. 719, 2nd entry in footnote 484).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian Исторический вестник

- ↑ Russian the river Орлик (река)

- ↑ Edition used, p. 529, 18. Zvo

- ^ Rudolf Marx in the afterword of the 1968 edition, p. 375, 10th Zvu

- ^ Reissner in the follow-up to the 1971 edition, p. 597, 14. Zvu