The Gross Clinic

|

| The Gross Clinic |

|---|

| Thomas Eakins , 1875 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 244 x 198 cm |

| Philadelphia Museum of Art |

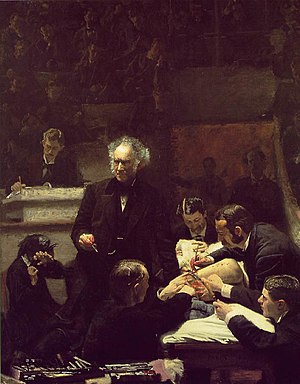

The Gross Clinic ( The Gross Clinic ) is a realistic oil painting from 1875 by Thomas Eakins cm in size 244 x 198th

Eakins himself saw the painting as his most important work. Today it is seen in art history as one of the most significant works by an American artist of the 19th century. It is also an important picture in terms of medical history. The comparison with Eakin's later painting The Agnew Clinic clearly shows the progress made in surgery. The Gross Clinic was sold at the turn of the year 2006/2007 for the record price of 68 million US dollars.

Image description

The painting shows the 70-year-old Samuel D. Gross , a famous surgeon, lecturing to a group of students at Jefferson Medical College . Gross wears a frock coat that is also his mascot: “a veteran of a hundred battles”. His eyes are in shadow and cannot be seen. The other doctors at the operating table are (from left to right): Dr. Charles S. Briggs, Dr. William Joseph Hearn (the anesthetist), Dr. James M. Barton (Gross' clinic chief) and Dr. Daniel M. Appel (who recently graduated from Jefferson Medical College). Another unnamed doctor is hidden behind Gross. The recorder behind Gross’s shoulder is Dr. Franklin West. The students can also be named, so in the back row sits third from the right, Robert CV Meyers (later the poet). However, some of the identified viewers are not medical students, but students of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts . Standing in the operating theater access tunnel are Hughey O'Donnell (a male nurse) and Dr. Samuel W. Gross (son of Gross and also a surgeon). Eakins himself, who is drawing, sits on the right-hand edge of the picture, also among those shown. The patient is usually identified as a young man or boy, although the painting does not make this clear for sure. The only woman in the picture is commonly seen as the patient's mother.

At the time of the picture, Gross has already made his cut, his hand with the scalpel is smeared with blood. It is brightly lit through a ceiling window. In System of Surgery , Gross names the time of day from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. as ideal for operations because of the light conditions, so it can be assumed that the operation shown falls within this time of day.

In the picture, Gross treats osteomyelitis of the thigh bone , which means that necrotic bone tissue is removed. In earlier times this disease would have resulted in the amputation of the affected limb. In the 19th century, however, conservative treatment as shown here was possible.

Eakins painted his signature on the front of the operating table .

Emergence

Eakins probably met Gross while studying art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts . It is also possible that he had attended Gross’s lectures. After training in Paris, Eakins returned to Philadelphia in 1870 and made a number of small-format pictures, alongside portraits of family members and friends, as well as numerous rowing pictures (see Max Schmitt in one ). However, the desired success had not materialized. At that time, the Centennial Exhibition was imminent in Philadelphia and Eakins decided to make a large-format portrait of the famous Gross, which he wanted to present at this world exhibition. He was almost the only artist in Philadelphia who took this opportunity. Eakins' reasoning may also have been influenced by the fact that Jefferson Medical College had begun to display pictures of their eminent doctors.

Eakins managed not only Gross himself, but also a number of other doctors and students to become models for him. Gross is said to have acted as his model so often that in the end he exclaimed, "Eakins, I wish you were dead!" Other information suggests that Eakins used photographs by Gross. No perspective studies of the painting have survived, but some oil studies of individual faces and the composition study shown on the right, which is an overpainting of a study of a rowing picture.

The Agnew Clinic

The Gross Clinic is often compared to the Agnew Clinic , Eakins' only other clinical picture. In contrast to the large portrait, the picture of Agnew was a commission, in fact the first commission since the scandal at the academy . In 1889, the University of Pennsylvania medical students who had raised $ 750 commissioned Eakins to produce a portrait of surgeon Dr. David Hayes Agnew (born November 24, 1818 in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, † March 22, 1892 in Philadelphia). The reason for this was his imminent retirement and so Eakins only had three months to complete this painting, which was not only his largest, but also restored his reputation. If the client had only expected a simple portrait, they received a complex painting with 27 individual portraits, for which both Agnew and the others depicted stood as models in Eakin's studio. As if that weren't enough, Eakins observed Agnew performing several of his operations. On the right edge is Dr. To see Fred H. Milliken whispering to Eakins (missing in the picture shown here). However, this portrait of Eakins is not a self-portrait, but comes from Susan Eakins, his wife. Because of the size of the canvas (189.2 × 331.5 cm), Eakins had to paint the lower parts of the painting while sitting on the floor.

The picture shows the progress that medicine has made in the few years since Gross retired. The operating theater is brightly artificially lit, the doctors and nurses wear white clothes and note the need for disinfection.

Although Agnew was famous for treating gunshot wounds, Eakins shows him doing a mastectomy. The painting was only on public display for a short time, so there was little response. However, the reactions that were received were negative.

classification

Another picture that Die Klinik Gross is compared with over and over again is the anatomy of Dr. Tulp by Rembrandt that Eakins was known most likely of his European tour. This, like other famous surgeons' pictures, does not show an operation but an anatomical lecture and the operation has not yet started. Another difference is the anatomical text, which is used as a guide in Tulp's lecture but does not appear in Eakin's picture.

The Gross Clinic is admired for its consistent realism and also has an important place in the documentation of medical history - both because it honors the emergence of surgery as a therapeutic discipline (before surgery was mainly amputation), and because it shows how the surgical theater in 19th century looked. The painting is based on an intervention observed by Eakins. Gross is shown here in a conservative operation, as opposed to an amputation (how the patient would have been treated in previous decades). The surgeons crowd around the anesthetized patient in their frock coats. This is just before the introduction of a hygienic surgical environment (see Asepsis ). A comparison with the Agnew Clinic shows the progress made in understanding infection prevention.

Interestingly, nothing in the picture itself determines the patient's gender. This fact makes the Gross Clinic unique, as it presents the viewer with a naked and bared body, but it is still not recognizable as male or female. Another amazing element of the picture is the single woman in the painting, seen in the middle distance, writhing in distress. She can be seen as a relative of the patient who acts as a companion. Her dramatic figure is in stark contrast to the calm, professional behavior of the men around the patient. This bloody and very blunt portrayal of surgery was shocking when it was first exhibited and still is for many viewers today.

That Eakins was aware of the violence in his picture can be inferred from a photograph in which Eakins and his students parody the picture: Instead of a scalpel, the actor who played Gross has an ax in his hand.

Critical reception

The painting was submitted but not accepted to the art department of the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 . The jurors were horrified by the bloody subject. Gross asserted his influence so that the painting was included in the medical section of the exhibition.

“We know of nothing in the line of portraiture that has ever been attempted in this city, or indeed in this country, that in any way approaches it.… This portrait of Dr. Gross is a great work — we know of nothing greater that has ever been executed in America. ”

“We know of no portrait work that has been attempted in this city, or even this country, that achieves it in any way. ... This portrait of Dr. Great is a great work - we know of no greater work that has ever been done in America. "

When it was later exhibited in a gallery, a critic in the New York Tribune wrote that it was

“One of the most powerful, horrible, yet fascinating pictures that has been painted anywhere in this century… but the more one praises it, the more one must condemn its admission to a gallery where men and women of weak nerves must be compelled to look at it, for not to look at it is impossible. "

“One of the strongest, most terrifying, yet most fascinating pictures painted in this country… but the more you praise it, the more you have to condemn it for being admitted to a gallery where the faint of heart men and women are forced to do it to look at, because not looking at it is impossible. "

Controversies surrounding the painting have centered on its violence and the melodramatic presence of the woman. Elizabeth Johns sees in the picture a celebration of a hero of modern life. Today's scholars have suggested that the image can be read in terms of castration anxiety and fantasies of domination over the body (e.g. Michael Fried), and that it documents Eakins' ambivalence in the representation of gender differences (e.g. Jennifer Doyle). Furthermore, the painting was seen as an analogy between painting and surgery that identified the artist's work with the advent of surgery as a respected profession.

In 2002 an art critic for The New York Times called it "hands down, the finest 19th-century American painting." In 2006, in response to the imminent sale of the painting, The New York Times published a “close reading” that outlines some of the various critical perspectives on this work of art.

Provenance

During the Centennial Exhibition, Jefferson Medical College acquired the painting, which Eakins later loaned several times for exhibitions. He also painted a black and white watercolor that was used to create an autotype (production of prints). After purchasing for $ 200, the painting was housed in the college building of Jefferson Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia until it was moved to Jefferson Alumni Hall in the mid-1980s . On November 11, 2006, the board of Thomas Jefferson University voted to sell the painting for $ 68 million to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the new Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art under construction in Bentonville . This is a record price for a work of art made in the United States before World War II.

The proposed sale was seen as an act of secrecy that many Philadelphia residents believed to be a fraud against the city's cultural heritage. In late November 2006, efforts began to hold the painting in Philadelphia, including a December 26th fund to raise money to purchase the painting and a plan to focus on a "historic item" provision in the Conservation Guidelines of the city. In a few weeks, the fund reached $ 30 million and on December 21, 2006, Wachovia Bank agreed to provide the difference until it was raised. The purchase has now been completed and the painting will alternate between the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts .

literature

- Elizabeth Johns: Thomas Eakins: The Heroism of Modern Life , Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1983, ISBN 0-691-00288-6

- One chapter of this book is dedicated to the Gross Clinic.

- Michael Fried: Realism, Writing, Disfiguration: On Thomas Eakins and Stephen Crane , University Of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1988, ISBN 0-226-26211-1

- In the section on Thomas Eakins, Fried deals with the Gross Clinic.

- Philip Dacey: The Mystery of Max Schmitt: Poems on the Life and Work of Thomas Eakins , Turning Point, Cincinnati, 2004, ISBN 1-932339-46-9

- The book of poems depicts the life and some of the works of Eakins in poems. A poem is included for each of the two hospital paintings.

- Jennifer Doyle, Sex, Scandal, and Thomas Eakins's The Gross Clinic in Representations (Fall 1999), included in Sex Objects: Art and the Dialectics of Desire (University of Minnesota Press, 2006) ISBN 0-8166-4526-4

Web links

- Leo J. O'Donovan: Medical vocation: From the transcendent horizon of healing , Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2003; 100 (51-52): A-3362 / B-2801 / C-2619

- Philadelphia Museum of Art: Ten Reasons to Keep Thomas Eakins' The Gross Clinic in Philadelphia

- Stefan C. Schatzki: The Agnew Clinic (PDF; 189 kB) on ajronline.org

- Philadelphia Works to Keep 'Gross' Treasure , broadcast December 14, 2006 on National Public Radio Morning Edition

- Wal-Mart Heir's Bid for Art Riles Philadelphians , broadcast December 14, 2006 on National Public Radio All Things Considered

Footnotes

- ↑ Alice A. Carter: The Essential Thomas Eakins , p. 42

- ↑ Alice A. Carter: The Essential Thomas Eakins , p. 44

- ↑ Elizabeth Johns: Thomas Eakins: The Heroism of Modern Life , p. 51

- ↑ Michael Kimmelman: Art Review: A Fire Stoking Realism. in The New York Times on June 21, 2002

- ↑ Kathryn Shattuck: Got Medicare? A $ 68 million operation in The New York Times on November 19, 2006

- ↑ Carol Vogel: Eakins Masterwork Is to Be Sold to Museums. in The New York Times on November 11, 2006

- ^ Stephan Salisbury: A divisive deal in The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 14, 2006

- ^ Selling off a city treasure in The Philadelphia Inquirer