Evangelical adult education

Evangelical adult education describes a special form of general adult education , which is characterized by special content, educational concepts and target groups. Similar to its Catholic counterpart ( Catholic adult education ), it is based on the Judeo-Christian tradition and above all on the message of the Gospel. In contrast to Catholic adult education, it is also based on the Reformation and its message of liberation. As can be seen from the various offers and institutional forms of Protestant adult education, the events focus on social issues, which offer a discussion forum, but also orientation aids. The offers also show that “Protestant” means an ecumenical and intercultural approach.

Organizational forms of Protestant adult education

At the European country level, since the Reformation, Protestant educational work has been in the interplay between church, state and society, as can be seen above all in denominational religious instruction, but also in the area of work with adults. In the countries and societies shaped by the Reformation, it is noticeable that in the post-Reformation centuries, thanks to the Enlightenment and awakening, the diaconal aspect came to the fore alongside the Enlightenment. Germany has a special role through the organization of Germany-wide church (EKD), regional churches and church districts, which is also reflected in the organization of Protestant adult education: At EKD level, the German Evangelical Working Group for Adult Education collects all activities nationwide that are carried out by its sub-organizations in the Regional churches and at church district and community level; a similar structure can be seen in the Anglican Church, where intergenerational learning is emphasized. In addition, the employees in evangelical adult education are organized in the Protestant and Anglican Network for life-long learning (EAEE), where they regularly exchange their experiences on a more informal European level. At the European state level, however, adult education is primarily organized by the state, church activities primarily at the community level. Analogous to the German Adult Education Association, there are also associations of further education organizations in other countries that strive for synergies.

At the regional level, city academies show how this approach is localized. In addition to these forms, there are also associations that feel committed to this approach and convey information, discussion and participation requirements between institutions and individuals.

At the community level, Protestant adult education encounters as transitory, compensatory, complementary or political education, where it is also about addressee-oriented clarification of individual and social requirements, contexts and conditions of the respective learning situation.

Concepts of evangelical adult education

If one considers the concepts of evangelical adult education of the last decades, either the existence and action orientation through preservation of the humanity in society, the language school of freedom, the Christian human education or the educational diakonia stand in the center. In summary, in 1983 the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) described adult education as a vital function of the church and a theologically necessary task within the framework of church educational responsibility. This was justified by the fact that adult education should either serve the individual as a medium for accompanying and orientation in the plurality of lifestyles and value orientations or should become the central, in practice mostly relatively non-binding bond in a life concept open to options. The empirical studies on Ev. Adult education, which is based on the statistics of the DEAE and its members, shows the diversity of models (including church music) at the various levels of church activity.

History of Protestant Adult Education

The more recent development history of Protestant adult education in the context of general adult education can be divided into different phases: While in the early modern period the adult catechumenate - influenced by the Reformation - was replaced by the promotion of general religious education (Bible translation, catechisms), the Enlightenment in the 18th Century for a secularization of Protestant educational work. Farmers ', workers' and craftsmen's associations, reading societies, Sunday and evening schools were founded, and learning was organized by socially defined groups themselves. In the course of the reform movement in the Weimar Republic, adult education was given a socially integrative function, which since the 1980s has been expanded to include an identity-creating function in the course of the change in everyday life and the return to the individual, as shown not least in numerous publications; as a result, evangelical adult education turned out to be not only church or community-oriented, but was also conceived as educational diaconia, theological information, language school or as a dialogue between church and world. These different concepts were increasingly integrated from 1990 onwards. B. Problems of gender equality, interculturality and ecumenism came into focus. In addition, the tension between more popular missionary-church-oriented and more society-related, general didactic approaches remained virulent.

Protestant adult education topics

The central conceptual guiding principle of evangelical adult education as for non-professional adult education as a whole is orientation towards the living environment of individuals, groups and societies. The resulting learning needs of people determine the learning opportunities in adult education. In contrast, institutional or ideological support interests take a back seat. This means that, in addition to theologically and philosophically oriented events, there are also events that are devoted to literature and art, educational, socio-critical and scientific-medical issues, as a look at the programs of the last decades shows.

Methods and organizational forms of Protestant adult education

As a life-world-oriented education, Protestant adult education combines individual and social, past and future-oriented learning in order to enable self-determined and participatory learning and life. This includes a corresponding participant-oriented course design in which the focus is on self-experience and reflection phases and the content primarily serves as impulses and orientation offers. It also shows that socially weaker groups, e.g. B. Refugees are increasingly invited to participate in order to enable them to participate in social life and discourse and to be able to speak in various fields. In view of the unavailability of faith, a multi-dimensional understanding of education in the sense of “faith formation” as imitation and replica based on European learning locations is important.

European examples of evangelical adult education

The described characteristics of adult education influenced by the Reformation are evident not only in the German context, but also in Europe, where the Reformation was formative. This applies especially to the coastal countries of the Baltic Sea, especially Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Estonia and Latvia, where the effects of the Reformation lead to a Lutheran state church; this also influenced the corresponding form of adult education. The Luther student and friend Philipp Melanchthon , who was not only considered a Praeceptor Germaniae, but also a praeceptor Scandinaviae, plays an important role. Its loci communes indicated secular and religious education and were the standard of education in Scandinavia, especially in Denmark; many of his students came from Denmark, Sweden and Finland.

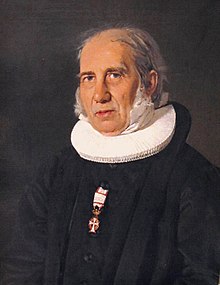

Similar to Melanchthon in the 16th century, Nikolai Frederik Severin Grundtvig in the 19th century was concerned with combining religiosity, values and lifestyle, tradition and enlightenment through education as "vox viva". Even after the end of the Lutheran state church and after the decline of church authority in the Scandinavian countries, the concern of both theologians and educators of such a popular education can be seen in the clear emphasis on informal education for all population groups and in the importance of personal development and value education that the Awakening movements were encouraged in the following centuries and led to the publication of new hymn books and new Bible translations in the 20th century.

In Estonia and Latvia, the former Livonia, which was also influenced by Lutheranism due to the proximity to Finland and Sweden, - a Luther student was also responsible for the implementation of the Reformation : Andreas Knopken, who - similar to Mikael Agricola in Finland and Olaus Petri in Sweden - relied on translations into the mother tongue and furthermore promoted singing and folk songs in the sense of a popular education, which - even under Russian rule - shaped the following centuries and led to the establishment of numerous community groups and initiatives, in which German and Estonian or Latvian was spoken in parallel.

Conclusion

The European examples of Protestant adult education underline the German findings, which were formulated as theses by the DEAE. There, the task of education in the Christian sense is named to bring the determination of man to the image of God to appear - in the individual self-perception as well as in the mutual recognition as subjects worthy of being so, instead of in the orientation towards one To make the dream of humans disappear as an always capable and suffering-free individual. With the belief in the unavailable human dignity that is assigned to every human being without any personal merit, the Protestant understanding of education contradicts the general tendency to orient educational processes primarily to their use for increasing human economic performance and market value. In order not to fall victim to the cost-benefit logic of the learning market, evangelical adult education is dependent on the complementarity of public educational responsibility of the state, church and associations, especially since it consists of a rather loose organizational structure of diverse institutions with different professional profiles of the employees in this context and with a high proportion of voluntary and voluntary work. However, in order not to be interpreted as an alleged pseudo-activity, participatory involvement of the individuals and institutions involved is required.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andreas Seiverth (ed.): Yearbook Evangelical Adult Education, Leipzig 2011

- ↑ Hans Peter Veraguth, EB Between Religion and Politics, Stuttgart 1976

- ↑ DEAE (1978), Adult education as a possible task. Karlsruhe.

- ^ Church of England (Ed.) Vision for Education, London 2016

- ↑ EAEA (Ed.): Adult Education in Europe 2014 - A Civil Society View

- ^ European Association for the Education of Adults

- ^ Friedrich Keienburg: Ev. Adult education as a task of the Ev. Academies. In: EBW (ed.). 1970-95: impulses, ideas, concepts. Dortmund 1985, 20-25.

- ^ Franz-Josef Hungs, Theological Adult Education as Learning Process, Mainz 1976 .; Herbert Rösener: Adult education as a task of the church, Bielefeld 1972; Helmut Schelsky, “Can continuous reflection be institutionalized?”, ZEE 1/1957, 153-174; Hans-Peter Veraguth: "Adult Education Between Religion and Politics", Stuttgart 1976

- ↑ Klaus Wegenast: Evangelical Adult Education, in: Gottfried Adam / Rainer Lachmann (eds.), Community Pedagogical Compendium, Göttingen 1994, 379-413

- ^ Franz Henrich and Wolfgang Böhme: Adult education in the plural society, Düsseldorf 1978

- ↑ Ernst Lange / Rüdiger Schloz: School of Freedom, Munich 1980

- ↑ Andreas Dannemann: Das Humanum in adult education, in: Bienert, W. (ed.): Evangelical adult education, Weiden 1967

- ↑ Werner Bienert: Evangelical adult education as educational diakonia - Theological foundation, in: Ders. Evangelical adult education, Weiden 1967

- ↑ EKD (ed.): Orientation in increasing disorientation, Gütersloh 1997

- ↑ Volker Elsenbast / Dietlind Fischer / Albrecht Schöll | / Matthias Spenn: Evangelical educational reporting. Feasibility study. Comenius Institute 2008

- ↑ Hans Tietgens (ed.): Approaches to the history of adult education, Bad Heilbrunn / Obb. 1985

- ^ Karl Ahlheim: Between Workers' Education and Mission, Stuttgart 1982; Werner Seitter: History of Adult Education, Bielefeld 2007

- ↑ Hans Peter Veraguth, EB Between Religion and Politics, Stuttgart 1976

- ↑ Günter Strunk, Art. Adult Education, in: TRE, Vol. 10, 1982, 180; Klaus Wegenast: Evangelical adult education, in: Gottfried Adam / Rainer Lachmann (ed.), Community Pedagogical Compendium, Göttingen 1994, 379-413.

- ^ Günter Apsel: On the order of possible adult education. In: EBW (ed.). 1970-95: impulses, ideas, concepts. Dortmund 1985, 26-37

- ^ Geert Franzenburg: Go and do likewise, Norderstedt 2016

- ^ Rolf Arnold: Lively learning. Baltmannsweiler 1996

- ↑ Wolfgang Bienert (ed.): Evangelical adult education. Pastures 1967; Günter Ebbrecht: Evangelical education in cosmopolitan responsibility. Gütersloh 1992

- ↑ EKD (ed.), Adult Education as a Task of the Evangelical Church, Gütersloh 1983

- ↑ Eberhard Harbsmeier, Faith and Education - Belief Education Peter Bubmann, Belief Education - Terminological and Theoretical Approaches, in: Martin Friedrich / Hans Jürgen Luibl (ed.): Belief education. The Transmission of Faith in European Protestantism (German and English), Leipzig 2012, 48-88; Peter Bubmann, Belief Education - Terminological and Theoretical Approaches, in: Martin Friedrich / Hans Jürgen Luibl (ed.): Belief Education. The Transmission of Faith in European Protestantism (German and English), Leipzig 2012, 89--

- ↑ Beatus Brenner (Ed.): Europe and Protestantism. Göttingen 1993; Michael Bünker : European Protestantism. In: Martin Friedrich , Hans Jürgen Luibl (Hrsg.): Belief formation. The Transmission of Faith in European Protestantism (German and English), Leipzig 2012, pp. 19–47; Geert Franzenburg, Draudziba Journal 2/2006; Ders., Trimda-Forum 6/2017; Martin Greschat: Protestantism in Europe, Darmstadt 2005

- ^ Stefan Rhein : Melanchthon and Europe. A search for clues. In: Jörg Haustein (ed.): Philipp Melanchthon - a trailblazer for ecumenism. Göttingen 1997, 46-63

- ↑ Inga Meincke: Vox viva - The "true enlightenment" of the Dane Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig. Winter, Heidelberg 2000

- ↑ Roland Sckerl: Spiritual awakening in the far north. Durmersheim 2007; Monika and Udo Tworuschka : Religions of the World. Munich 1996; on the context: EAEA (2011): EAEA (2011): Country report Denmark. (Helsinki). www.eaea.org/country/denmark; Country report Norway. (Helsinki). www.eaea.org/country/norway (October 2017); EAEA (2011): Country report Finland. (Helsinki). www.eaea.org/country/finland (October 2017); EAEA (2011): Country report Sweden. (Helsinki). www.eaea.org/country/sweden (October 2017)

- ^ Kurt Kentmann, Gerhard Plath: From the church life of the German Evangelical Lutheran parishes in Estonia up to the resettlement in 1939. Hanover 1969; Reinhard Wittram: The Reformation in Livonia. Göttingen 1956; for the context cf. Country report Estonia. (Helsinki). www.eaea.org/country/estonia (October 2017); EAEA (2011): Country report Latvia. (Helsinki). www.eaea.org/country/latvia (October 2017).

- ↑ DEAE (ed.): Adult education as a possible task. Karlsruhe 1978.

- ↑ EKD (ed.): Orientation in increasing disorientation. Evangelical adult education in church sponsorship. Gütersloh 1997; Andreas Seiverth (ed.): Yearbook Evangelical Adult Education, Leipzig 2011

literature

- Martin Friedrich / Hans Jürgen Luibl (ed.): Belief education. The Transmission of Faith in European Protestantism (German and English), Leipzig 2012

- Ekkehard Nuissl / Susanne Lattke / Henning Pätzold: European perspectives on further education. Bielefeld 2010

- Andreas Seiverth: Re-Visions of Protestant Adult Education. Oriented towards people. Bielefeld 2002

- Richard Stang / Claudia Hesse (eds.) :. Learning centers. New organizational concepts for lifelong learning in Europe. Bielefeld 2006

- Christine Zeuner: Learning without borders: European perspectives on adult education. In R. Arnold & A. Pachner (ed.), Learning in the course of life (Fundamentals of professional and adult education, vol. 69, pp. 145–162). Baltmannsweiler 2011

- Friedrich Ziegel (ed.): Chances of learning. Protestant contributions to adult education, Munich 1972