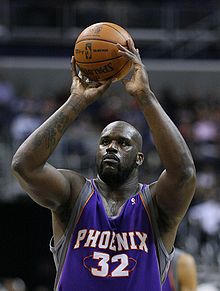

Hack-a-Shaq

Hack-a-Shaq is a commonly used term for a basketball defensive tactic that uses deliberate fouls. The name is derived from the English term "hack" (for "hack" or "bat") and the nickname of the player Shaquille O'Neal . The tactic was first used in 1997 by the Dallas Mavericks under coach Don Nelson . It was very effective mainly because O'Neal was a gifted basketball player, but had a miss rate of almost 50% on the free throw line.

background

Repeated, deliberate foul play strategy

It is part of the basic tactical repertoire of basketball to use deliberate fouls shortly before the end of regular time in order to prevent the opponent who is just in the lead from downplaying the playing time. The consequence of this tactic is continuous free throws for the opposing team. Since even the best teams in the NBA achieve an average of only 1.1 points per attack, a free throw rate of 55% is enough to bring long-term disadvantages to the foul playing team. However, since the average NBA player hits well over 70% of his free throws, the tactic was only used in situations where the opposing team could otherwise achieve victory simply by repeatedly running down the shot clock . In order to improve the chances of one's own team a little, players with comparatively poor free-throwing skills were ideally fouled, since the free throws always had to be carried out by the fouled player. This led to more and more players being fouled who were not in possession of the ball. Since the opposing coach was aware of this behavior, he was able to react and only set up good free-throw shooters in the final phase. This behavior first became a problem for the NBA when one of the league's superstars, Wilt Chamberlain, was permanently fouled from the free throw line due to his poor hit rate.

Wilt Chamberlain and the off-the-ball foul rule

Wilt Chamberlain was one of the best players in the league and important to his team. Should a game not be decided shortly before the end, Chamberlain was definitely on the field. However, he was a very poor free throw shooter throughout his career, hitting only 51% of all free throws. This made him a popular target for the opposing team, while he tried everything himself to avoid being fouled. As a result, Chamberlain was practically completely taken out of the game, as he was permanently busy playing catch with the opposing defense.

This behavior made the game unattractive and caused displeasure among fans, so that the NBA was forced to act. In response, a new rule on off-the-ball fouls was introduced in the closing stages. This stipulated that in the event of a foul on a player who is neither leading the ball nor currently trying to get to it, the attacking team remains in possession of the ball in the last two minutes of the game after one or two free throws have been executed. Since the only point of deliberate fouls was to quickly end the opponent's attack, only the player in possession was fouled from now on, which eliminated the problems for Chamberlain and other bad shooters.

Looking back on the introduction of the rule in 2004, Pat Riley said:

" The reason they have that rule is that fouling someone off-the-ball looks foolish. . . Some of the funniest things I ever saw were players that used to chase Wilt Chamberlain like it was hide-and-seek. Wilt would run away from people, and the league changed the rule based on how silly that looked. "

The reason for this rule is because it looks silly to foul someone without possession. . . Some of the funnest I've ever seen were players who chased Wilt Chamberlain like they were catching . Wilt ran away from people and the league changed the rule because it looked so ridiculous.

The invention of the Hack-a-Shaq tactic

Don Nelson’s idea

Although there have been numerous game situations in which deliberate fouls have been used, this has usually been limited to close residues in the closing stages. Intentional fouls at another point in time seemed to make little sense because of the improved chances of scoring for the opponent. At the end of the 1990s, Don Nelson, at that time coach of the Dallas Mavericks, considered that the targeted selection of a very poor free throw shooter could result in a disadvantage for the team of the fouled player.

Since Nelson could not only use the strategy in the final phase, there were no problems with the "off-the-ball foul" rule and again the worst thrower could be fouled without having to carry the ball. Nelson's idea, therefore, cannot be seen as a new strategy. Rather, he used a well-known strategy designed to stop the music box in such a way that it does not maximize the remaining playing time, but rather minimizes the points scored by the opponent.

Hack-a-Rodman

The new tactic was first used in 1997 against Dennis Rodman and the Chicago Bulls . At the time of the game, Rodman had only hit 39% of his free throws that season. This would result in only 0.76 points per attack, far less than the 1.1 points that a good team achieves on average. The tactic could not be used throughout the game as a player would be suspended for the remainder of the game after the sixth personal foul. To get around this problem, Nelson mainly used bankers for the fouls, who otherwise would not be in danger of committing further fouls and whose loss would be manageable. In theory, the Mavericks should have an advantage, as Rodman would score significantly fewer points on the free-throw line than the Bulls' strong offensive with Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen . In fact, Rodman hit 9 of 12 free throws in the game, which failed the tactic and the Bulls won. Because of this failure, the tactic was quickly forgotten. The only thing that was remembered was that Maverick player Bubba Wells set an NBA record as the player with the fewest minutes played before the sixth personal foul.

Nonetheless, Nelson used the strategy again in 1999 against Shaquille O'Neal and the Los Angeles Lakers . This time, coaches from other NBA teams followed the same idea and played the same tactic against O'Neal, who at the time only hit 53% of his free throws. For this reason, this tactic came to be known as "Hack-a-Shaq", even though it was first used two years earlier against Dennis Rodman.

Shaquille O'Neal's reaction

Shaquille O'Neal was generally defiant about the strategy used against him. He confidently claimed to hit the really important free throws regularly so that the opposing team's strategy would not be successful.

In the 2000/01 season, O'Neal reached its worst rate to date with 38% from the free throw line by mid-December. As a serious problem arose for the Lakers, they hired with Ed Palubinskas a free throw coach for O'Neal, who converted 92.4% of his free throws as a player. Practice seemed to be paying off, with O'Neal hitting nearly 68% off the line in the last 15 games of the season.

Nevertheless, O'Neal ended the collaboration with Ed Palubinskas and has not been able to reach the quota of early 2001 since then. He scored slightly better in the next two years than in his previous career, but only achieved an average of over 60% in the 2002/03 season. After this season he stayed permanently below 50%, but still refused further special training.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Günter Steppich: Stopping the clock. In: Basketball Co @ ches Corner. February 21, 2012, accessed June 6, 2018 .

- ↑ teamrankings.com: NBA Team Offensive Efficiency , accessed on June 6, 2018.

- ↑ NBA.com: Statistics by Wilt Chamberlain ( Memento of the original from June 19, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed on June 4, 2018.

- ↑ Markus Unckrich: Hack-a-Player-Rule? In: Basketb.com. July 4, 2016, accessed June 4, 2018 .

- ↑ Elljah Ackerman: Understanding Hack-a-Shaq: Why The Wacky Strategy Should Stay. In: Vavel.com. April 29, 2015, accessed June 4, 2018 .

- ↑ Andrew Keh: The Birth of Hack-a-Shaq. In: NYTimes.com. April 30, 2016, accessed June 4, 2018 .

- ^ Dennis Rodman 1997-98 Game Log. In: Basketball Reference. Retrieved June 4, 2018 .