Hasta + Coda theory

the hasta and the horizontal line forms the coda.

The Hasta + Coda theory , also Hasta-Coda theory , is a theory of the linguist Herbert Brekle to describe and explain our current letter forms . Accordingly, the division of the letters into two parts played an important role in the development of the Latin alphabet and its predecessor alphabets . These parts are a main vertical line called a hasta and the horizontal extensions called coda or codae. About half of our alphabet consists of letter forms with a hasta plus code structure. This applies both to the capital letters ( upper case ) and for the lower case ( minuscule ).

definition

Brekle defines Hasta and Coda as follows:

Such figures are thus vertically- axially asymmetrical . This Hasta-plus code structure also applies in principle to corresponding letter forms from earlier stages of development of the Latin alphabet ( Protosinaitic , Phoenician and Greek ). This structure also shows - in changing composition - about half of the letters of the respective alphabet. The letters in the other half show different symmetry properties: vertically- axially symmetric or point-symmetric .

The "structure type hasta plus coda of letters can be shown ... through cognitive - psychological criteria as a 'realistic' structural principle and not as a merely constructed shape type".

Examples

The hasta-plus code structure played a decisive role in the differentiation of a minuscule script from Roman capital letters from the 1st century AD. A few examples from today's so-called publication and some illustrations illustrate the above, more theoretical explanations. Semitic- Greek stages of development of the Latin alphabet are not considered in the following.

D to d

Using these two current letter forms, it is possible to show how the lowercase form d developed from the capital form D in ancient Roman times. Both forms have a hasta plus code structure. An essential difference between the two is that D is oriented dextrally, ie "looks" to the right, while d is oriented sinistrally (to the left). This breaks a regularity: the codae of other letter forms such as B / b, F / f, h, L / l, P / p and R / r are dextral oriented. An exception is the q ( see below under G to g ).

At this point the criterion of “free vertical hasta” must be introduced.

Brekle defines: “The term 'free hasta' is to be understood as that part of a letter form that is not enclosed or limited in its entire length by code parts; for example F, L, P. “However, this criterion was not fulfilled by the uppercase D in the classical Roman period. The way to solve the problem leads through handwritten varieties as they appear in private letters and bureaucratic documents (see Fig. 1 and 8).

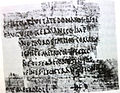

In Fig. 1 the word form DONATOS appears in the 1st line.

The D shows a slight overshoot of the code sheet upwards. In Fig. 1 - written less formally than Fig. 8 - CEDO appears in the fifth line. Here the code sheet has mutated into a straight diagonal line. In the papyrus fragment de bellis macedonicis (Fig. 7) - written a century after Fig. 1 - you can see the new form of the D / d already conventionalized. A final development step consists in the verticalization of the “oblique” old Codastrich, which has thus completely become the new Hasta.

In addition to the above-mentioned criterion of "free vertical hasta", the new regularity that has arisen as a result of system constraints should be pointed out: The distribution of the ascenders and descenders [the new minuscule forms that fit into a four-line scheme] is regulated in such a way that forms with a coda figure at the bottom of the hasta this is assigned an ascender (e.g. b, d, h, l; B is the predecessor form of b, in which the upper coda arc of B merges with the hasta and thus creates a free hasta) . If the coda figure sits on top of the hasta, it has a descender: f, p. Today, the letter f only has a handwritten or, in the cursive antiqua and Fraktur font, an additional descender, because its upper code line appears to be too "weak" compared to the arched code figures. For f with ascender and descender, compare the names 'Humfredus' and 'aba florianus' in Fig. 3.

E to e

In Fig. 2, second and fifth lines, two E-shapes appear which cannot be recognized as such. The upper and lower code lines of the E are slightly curved to the right and merge with the hasta, i.e. they are written in one go, which leads to the loss of the original hasta plus code structure (see Fig. 5 and 6). In the latter, the upper arch of the E / e almost touches the middle codastroke. The Carolingian minuscule form e is thus already established (see Fig. 3).

G to g

G is derived from the shape of the C, which in turn is derived from the Greek right-angled gamma form. G is a new letter in the Roman alphabet that was distinguished from C by adding a short dash to the lower half-arc (e.g. in Fig. 2, fourth line, and Fig. 6). With these two alphabets one recognizes a stage of development. The Hilarius-G shows a sweeping smear down to the left. The second [feather] pull, which was bent to the left in the lower length, was necessary to prevent a homomorphism collision with the shape q. "What was important for the emergence of the Carolingian form g was the bending of the downward stroke to the left and the closure of the arch with the downward stroke added above." As in Fig. 3, gisela in the fourth line, and the variants in the second column in Hildigarda , reg (ina) .

This illustration also clearly shows that with the canonization of Carolingian minuscule script as a normal book script, the stage of our current lowercase alphabet was already reached. Except for a few details like the long s and the f with descender in the print.

Font development

Brekle concludes his investigations with the preliminary conclusion,

“That essential elements of the later lowercase typeface were already laid out in Roman everyday writing [and chronologically parallel scripts]: the transgression of the old two-line system of the capitalis through the formation of consistently [and regular, hasta plus coda principle] used ascender and / or descender forms in the direction of a four-line system and, in connection with this, the preforming of numerous later minuscule letter forms. "

gallery

literature

- Herbert E. Brekle : The antiquarian line from approx. -1500 to approx. 1500. Studies on the morphogenesis of the western alphabet on a cognitivistic basis , Nodus, Münster 1994, ISBN 3-89323-259-1

- Herbert E. Brekle: “News about upper and lower case letters. Theoretical justification of the development of the Roman capital letters to lowercase writing ” , in: Linguistischeberichte , Volume 155, 1995, pp. 3–21

- Herbert E. Brekle: “The taming of Pompeian debauchery. Historical and theoretical justification of our current letter forms ” , in: Linguistic Reports , Volume 160, 1995, pp. 427–466

- Herbert E. Brekle: "Boundary conditions and regularities in the historical development process of our letter forms" , in: Osnabrücker Contributions to Language Theory (OBST), Volume 56, 1997, pp. 1-10

- Herbert E. Brekle: “From the cattle head to the Abc” , in: Spectrum of Science , April 2005, pp. 44–51

- Herbert E. Brekle: Supplements to the article "From the cattle head to the alphabet" , 2010

- Agustín Millares Carlo: Tratado de paleografía española , Espasa-Calpe, 1983, ISBN 978-84-239-4986-1

- Jean Mallon: Paléographie romaine , Scripturae Monumenta et Studia III, Madrid 1952

further reading

- Herbert E. Brekle: " Some Thoughts on a Historico-Genetic Theory of the Lettershapes of our Alphabet ", in: WC Watt (Ed.): Writing Systems and Cognition: Perspectives from Psychology, Physiology, Linguistics, and Semiotics , Neuropsychology and Cognition , Volume 6, Kluwer, Dordrecht 1994, pp. 129-139 ISBN 0-7923-2592-3

Individual evidence

- ↑ Brekle 1994, p. 57

- ↑ See Brekle 1994, pp. 61f. and 82-85

- ↑ Brekle 1994, p. 59; see. see chapter 3.3 “The shape of the letters: reading and writing from a cognitivistic point of view”, pp. 46–64

- ↑ See Brekle 1995 (two articles) and Brekle 2005, pp. 173, 191

- ↑ See Brekle 1994, Chapter 5 “On the morphogenesis of the Old Semitic and Northwest Semitic Alphabet from approx. -1600 to approx. -800”. For the ancient Greek alphabet cf. Brekle 1994, Chapter 6 "Morphological development of the Greek alphabet from approx. -750 to approx. 1500".

- ↑ Brekle 1994, p. 173

- ↑ Brekle 1994, p. 191

- ↑ Brekle 1994, p. 192; Brekle 2005

- ↑ Brekle 1994, p. 192

- ↑ See Brekle 1994, p. 192

- ↑ Brekle 1994, p. 193