Heiligenstadt Testament

The Heiligenstädter Testament is a letter from the composer Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) to his brothers Kaspar Karl and Johann from 1802, in which he expressed his despair over the progressive deafness and the believed death.

Emergence

From May to October 1802 Beethoven went to the mineral-rich spring of the bathing establishment in Heiligenstadt near Vienna to treat the gastric complaints from which he often suffered, combined with severe colic. His doctor Johann Adam Schmidt also promised a cure for his progressive hearing impairment .

How did Beethoven get his hearing problem?

Beethoven returned from Berlin to Vienna in June 1796 after a four-month concert tour. There he was most likely infected with flea spotted fever from a rat flea bite . According to the doctor Aloys Weißenbach , who was in contact with Beethoven in the 1810s, Beethoven suffered from “common typhus”. This was only associated with flea spotted fever after 1836. This so-called murine typhus was fatal in 4 percent of patients in the time before antibiotics were discovered. 15 percent of the sick suffered damage to the nervous system as a secondary disease, including incurable damage to the hearing in relatively few people.

Place of writing

Beethoven lived in a detached farmhouse outside of Heiligenstadt on the way to Nussdorf at Herrengasse 6 (today: Probusgasse 6) . There the 31-year-old wrote a letter to his brothers on October 6th, in which he emphatically describes the concern about his deteriorating hearing, his social isolation, the thoughts of suicide that have germinated and overcome, and regulates his estate. Although he wrote a postscript on October 10, folded the sheet of paper and sealed it, he did not send the letter, which was only found in the estate in 1827. Alongside the letter to the immortal beloved , it is one of Beethoven's most personal writings.

content

The reason for putting down the will was the increasingly deteriorating state of health of Beethoven, but especially the desperation due to his progressive deafness, which became apparent as early as 1796. The first two thirds of the text takes Beethoven's justification to his fellow world, to whom he gives to understand that he is not "hostile, stubborn or misanthropic", but that: "I had to isolate myself early, spend my life lonely", since he "repelled" by his deafness, because it was impossible for him to announce: "speak louder, scream, because I am deaf". To do without the loss of his sense of hearing "which with me should be in a more perfect degree than in others, a meaning that I once had in the greatest perfection, in a perfection that few in my field have certainly had" closes him off the company and he asks: "So excuse me, if you will see me shrink back where I liked to mingle with you, double woe is my misfortune." He then notes his experience in the presence of Ferdinand Ries , when he felt the shame on a hike: “But what humiliation if someone stood next to me and heard a flute from afar and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing, and so did I heard nothing ”. This plunged him into despair and "there was little missing, and I ended my life myself - only she the art , she held me back".

Only then does Beethoven move on to the testamentary part - which in this form, according to the given Austrian case law, would have reached into Beethoven's mind anyway. The later wills of 1823 and 1827 no longer provided for the division of the inheritance between the brothers. He asks his brothers "as soon as I am dead and Professor Schmid is still alive, ask him in my name to describe my illness", she then explains to his heirs, asks them to "share it honestly, and get along and help one another, what you did against me, you know, you have long been forgiven, I thank you brother Carl in particular for your devotion shown to me in this later, later time ”. So he still makes distinctions between the brothers, especially by not mentioning Nikolaus Johann (whom he calls a "pseudo-brother" on another occasion) by name, but leaving a space in the three corresponding places. He also mentions the instruments that he had received from Prince Lichnowsky , then turns back to the general public by writing: “I will be happy to meet death - if it comes before I have had the opportunity to do all of my artistic skills unfold, he will still come too early for me despite my hard fate ”, before he concludes, turning back to his brothers:“ Farewell and don't forget me completely in death, I have earned it for you by being in My life often thought of you to make you happy, be it - “.

The postscript of October 10 shows him again in a melancholy mood. He gives up all hope: “She has to leave me completely now, as the autumn leaves are falling, withered, so - she too has become dry for me, almost as I came here - I go away - even the High Courage often animated me in the beautiful summer days - it has disappeared ”and concludes:“ When, oh deity - can I feel it against nature and man in the temple - never? - no - o it would be too hard ".

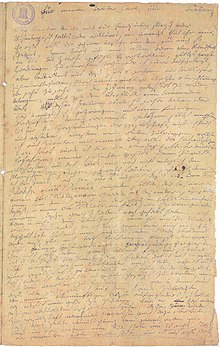

On the document there are still two owner entries by someone else's hand: from Jakob von Hotschevar, who received it from Artaria on September 21, 1827, and from Johanna van Beethoven, who received it from him.

Only after Beethoven's death in March 1827 was the document found, as was the letter to the immortal beloved , and was soon given the name "Heiligenstadt Testament".

The original has been in the Hamburg State and University Library as a gift from the Swedish singer Jenny Lind since 1888 .

literature

- Ludwig van Beethoven, Heiligenstädter Testament, ed. by Sieghard Brandenburg , Beethoven-Haus, Bonn 1997, ( annual editions of the Beethoven-Haus association 14 = 1997, ZDB -ID 991144-3 ), (facsimile edition)

- Ludwig van Beethoven, correspondence. Complete edition , ed. by Sieghard Brandenburg, Volume 1, Munich 1996, pp. 121-125

Internet

- ND VI 4281

- Heiligenstadt Testament spoken by Konstantin Marsch

proof

- ↑ Noticeable is the incorrect age specification "in my 28th year" in the letter. Beethoven was already 31 years old. He usually kept himself younger than he was for two years, believing he was born in 1772 because his father had made the thirteen-year-old appear as an "eleven year old child prodigy".

- ↑ For the documentation of this and the following passages, see the original version of the Heiligenstadt Testament on Wikisource

- ↑ Signature: ND VI 4281. Hamburg State and University Library, accessed on August 18, 2014 .