Intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo

The intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy ( Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, IS-TDP ) is a psychodynamic short-term psychotherapy method , which by Canadian psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Habib Davanloo ( McGill University was developed Montreal) from 1960 to 1990. For patients who have been traumatized before the age of four and whose families have passed on pathogenic relationship patterns across generations, Davanloo has expanded its procedure over the past 20 years. He calls this in-depth procedure " Mobilization of the Unconscious and IS-TDP ".

The aim of the IS-TDP is to help the patient get to the unconscious roots of their problems, which Davanloo believes have been pushed aside because they are too terrifying or too painful. He describes his technique as intense , because it is supposed to allow the repressed feelings to be experienced to the highest possible degree; as short , because she wants to achieve this experience as quickly as possible; and as psychodynamic because it works with unconscious forces and transference feelings.

Symptoms can be anxiety and depression, but also physical complaints without a medically identifiable cause such as headache, shortness of breath, diarrhea or sudden attacks of weakness. According to the IS-TDP, such symptoms should occur in depressing situations in which painful or forbidden feelings are triggered without being consciously perceived. In psychiatry, these phenomena are classified as "somatoform disorders" (DSM-IV). DSM-IV-TR .

Davanloo recorded therapeutic sessions on film to determine which interventions were best suited to overcoming the resistance that served to keep painful or terrifying feelings out of awareness and to prevent human closeness. The audiovisual recording of all therapy sessions is part of the IS-TDP. The recordings are used for self-examination by the therapist and for supervision as well as for teaching and research.

History and basics

In 1895 Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud published their studies on hysteria . Breuer was able to alleviate some physical symptoms by encouraging patients to talk about difficult emotions in their lives. This cure became known as catharsis , and experiencing previously forbidden or painful feelings was called venting . Freud tried various techniques to overcome the displacement resistance. He switched from hypnosis to free association , interpretation of resistance, and interpretation of dreams . The therapies lasted longer with each step.

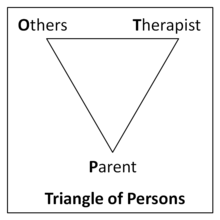

From the 1930s to the 1950s, numerous analysts tried to shorten the duration of therapy, including Sándor Ferenczi , Franz Alexander , Peter Sifneos, David Malan, and Habib Davanloo. But the patients who responded well to the therapy continued to represent only a small minority; the vast majority of patients could not be reached even with the newly developed techniques. Overcoming the resistance was the core problem. Malan described a resistance model that had originally been presented by Ezriel as a conflict triangle. At the lower end of the triangle are the impulsive unconscious feelings of the patient. Davanloo added that these were the patient's archaic childish feelings. If these feelings threaten to break through into consciousness, then they trigger feelings of fear and defense mechanisms .

Malan's second triangle, the person triangle (originally proposed by Menninger), says that feelings that arose in the past can be triggered in current relationships - including the relationship with the therapist. Empirical support came from Bowlby's attachment theory . British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby explored the effects of adverse experiences with primary caregivers during early life. He named innate behaviors (e.g. screaming) that aim to be physically close to the mother. A bond break can cause long-lasting trauma as well as psychiatric disorders, relationship disorders and a reduced zest for life. Bowlby found high correlations between injurious early life circumstances and numerous disorders, including persistent depression, anxiety disorders, and delinquency in adult life.

In the 1960s, Davanloo worked with patients who suffered from symptom neuroses and character disorders and who were traumatized by the loss of early attachment figures or by experiences of violence. He found the rise in complex transference feelings from the patient to the therapist signaled by signs of unconscious fear (for example, through muscle tension). In a constructive working atmosphere, repressed feelings could then be made aware. The first feeling that emerged could be intense sadness or archaic anger towards the therapist. The patients learned to physically experience these impulses of anger and to allow the associated ideas of violence.

The patient's anger is a result of past injuries and a result of unsuccessful attempts by the child to establish closeness to one of their caregivers: Pain creates anger. The therapist waits for the patient to make that connection - for the unconscious working alliance to take the lead. In the IS-TDP there is no room for the therapist to interpret; the patient himself establishes the connection to his biography.

Feelings of guilt arise because the early desire for revenge was once aimed at a loved one. According to Davanloo, unconscious feelings of guilt create symptoms, character problems and self-sabotage, an equally unconscious need for self-punishment, a need for suffering and loneliness. The unconscious feelings of guilt are also physically experienced in the therapeutic session. Then, when patients remember the initially hurtful situation, pain and sadness come to the fore. Davanloo said that the unconscious feelings that come into consciousness in therapeutic work always run on the associated neurophysiological pathways and thus become tangible for the patient and visible for the therapist.

Interventions

Davanloo divided the work process between patient and therapist into phases, from capturing the problems to working on the defense mechanisms and breaking through into the unconscious to jointly analyzing the schedule. To overcome the defense mechanisms, he condensed his technique into three forms of intervention: pressure , challenge and head-on collision (HOC) . The head-on collision can be understood as a "head-on collision with the resistance"; it is the strongest form of challenge. The interventions are individually adapted in order to achieve a pleasant working process for the patient. Classic psychoanalytic techniques such as free association on the part of the patient or interpretation on the part of the therapist have no place in the IS-TDP. Nor is a transference neurosis admitted.

pressure

The main goal of pressure is to mobilize the unconscious. Pressure is a major element in the IS-TDP and can take many different forms. For example, in the case of a generalizing description, the therapist asks for a specific example, for a scene, for details, or he formulates a concise summary. The therapist can also ask about the patient's feelings as soon as interpersonal tension develops. Pressure can also be exerted on the patient's will: "You decide whether you want to give up your defense mechanisms or not - after all, it's your life that is at stake here." The build-up of pressure begins in the first interview with the first introductory one Therapist's sentence: "What seems to be the problem for which you are looking for help?"

Patients with little resistance react very positively. In patients with more resistance, pressure leads to an increase in unconscious fear - and thus to an intensification of the resistance. This requires further forms of intervention.

Challenge

The defense mechanisms can be challenged in many ways: addressing the defense directly, questioning its apparent benefit - the point of these interventions is to make the patient's defense mechanisms visible to the patient. “Could that smile be a way of trying to cover up your feelings?” “I know you are not doing this on purpose and consciously, but that does not solve your problem.” Challenge means giving the patient the highest appreciation counter but disrespect the defense mechanisms.

A challenge can only be applied once the patient's defense mechanisms have formed. It must be done sensitively and precisely.

Head-on collision

In the head-on collision , the IS-TDP differs completely from the classic analysis and most other therapy methods. While other therapists initially allow the patient to indulge in resistance, the destructive power of resistance and its consequences are shown here from the start. At the same time, the patient's will, resources and autonomy are challenged very clearly and directly. The head-on collision is made up of a whole bundle of interventions that not only refer to a defense mechanism, but also target the defense system as a whole.

Here is a schematic example of a head-on collision with resistance to proximity, as is often used at the beginning of therapy:

“Obviously you have serious problems.

I am assuming that you came to therapy of your own free will. Is that correct?

It is our common task to get to the core and engine of your problems, which stem from destructive forces from your past. We would like to come together there, with your and my help.

But if you look at the destructive pattern of behavior that you are developing towards me right now, how you keep me at a distance, how you don't allow me to get really close to you - what happens until the end of this hour? I will not be able to really understand you. And I will be of no help to you.

And I suspect I'm not the only person you keep your distance like that. Check it out, you know your life much better than I do.

As long as you maintain this invisible wall, as long as you hold on to this need, not to allow me to get really close to you, this process is in danger of failing.

And why should you let that happen?

Let's see what we both do and what you are doing here against this wall! "

In drastic terms, the head-on collision makes the consequences of failure clear for the patient - and at the same time encourages him that success is within reach.

Proof of effectiveness

Davanloo's research was initially published as single case studies with approximately 200 patients. He has archived his cases in a video collection that he uses for lectures. Davanloo considers the effectiveness for the IS-TDP in symptomatic neuroses, in somatoform disorders and in personality disorders to be proven.

To date, there have been 19 published studies on the effectiveness of IS-TDP, seven of which are randomized-controlled, ten case studies and two non-randomized:

- Personality Disorders

- Treatment resistant and complex depression

- Panic Disorder

- Headache

- Functional Movement Disorders

- Medically Unexplained Symptoms (Somatization)

- Clinical and cost effectiveness in a private practice setting

A Cochrane systematic review is also available, which reviews the effectiveness of short-term therapies for mental illness. The neuroscientist and Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel says of Davanloo's technique and its effectiveness that it provides relief for mental disorders.

literature

- Davanloo, H. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy. In Kaplan, H. and Sadock, B. (eds), Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry , 8th ed, Vol 2, Chapter 30.9, 2628-2652. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

- Davanloo, Habib. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Selected Papers of Habib Davanloo, MD. Wiley, 2000.

- Davanloo, Habib. Unlocking the unconscious: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD . New York: Wiley, 1995.

- Davanloo, Habib. Basic Principles and Techniques in Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy . Jason Aronson Publishers, 1994.

- Davanloo, Habib. Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy . Jason Aronson Publishers, 1992.

- Gottwik, G. et al. The technique of intensive psychodynamic KZT according to Davanloo , (with case history). In Psychodynamische Psychotherapie, 32012, 145ff, 2012

- Gottwik, G. (Ed.) Intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo . Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag, 2009

- Jordi, A. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy . In psychotherapist 48: 179-189 Heidelberg: Springer, 2003.

- Sifneos, Peter. Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Evaluation and Technique . Springer, 1987.

- Sporer, U. Video analysis of physical signals of feelings and avoidance of feelings during intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo . In SKD Sulz et al. (Ed.), Psychoanalysis discovers the body. Or: No psychotherapy without body work ?, pp. 217–232. CIP-Medien: Munich, 2005

- Trondle, P. Psychotherapy, dynamic-intensive-direct. Textbook on intensive dynamic short psychotherapy . Psychosozial-Verlag, 2005

Web links

References

- ^ Davanloo, H. "Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy." In Kaplan, H. and Sadock, B. (eds), Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry , 8th ed, Vol 2, Chapter 30.9, 2628-2652. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (1995) Intensive short-term psychotherapy with highly resistant patients. I. Handling resistance. In H. Davanloo, Unlocking the unconscious: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD . New York: Wiley. (pp. 1-27).

- ↑ Malan, D. & Coughlin Della Selva, P. (2006). Lives transformed: A revolutionary method of dynamic psychotherapy (Rev. ed.). London: Karnac Books.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (1995). The technique of unlocking the unconscious in patients suffering from functional disorders. Part 1. Restructuring Ego's defenses. In H. Davanloo, Unlocking the unconscious: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD . New York: Wiley. (pp. 283-306).

- ↑ Malan, D. & Coughlin Della Selva, P. (2006). Lives transformed: A revolutionary method of dynamic psychotherapy (Rev. ed.). London: Karnac Books. Page 255.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (2000). Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: Spectrum of psychoneurotic disorders. In H. Davanloo: Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD . (pp. 1-35)

- ^ Freud, S. & Breuer, J. (1957). Studies on Hysteria. In J. Strachey & A. Strachey (Eds. & Trans). New York: Basic Books, Inc. (Original work published 1895)

- ↑ Gay, P. (2006). Freud: A life for our time . USA: WW Norton & Company, Ltd. Pages 49-50, 71-73, 107.

- ↑ Freud, S. (1937c). The finite and the infinite analysis. GW, 16; Analysis terminable and interminable. SE, 23: 209-253.

- ^ Della Selva P. Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Theory and Technique. 1996. Wiley and Sons. Cf: Foreword by David Malan.

- ↑ Ezriel, H. (1952). Notes on psychoanalytic group therapy: II. Interpretation. Research Psychiatry, 15,119.

- ↑ Menninger, K. (1958). Theory of psychoanalytic technique. New York, Basic Books.

- ^ Bowlby J. Separation . Vol II in Attachment and Loss . 1969. Pimlico.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (1995). Intensive short-term psychotherapy with highly resistant patients. I. Handling resistance. In H. Davanloo, Unlocking the unconscious: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD. New York: Wiley. (pp. 1-27).

- ↑ Gottwik, G. (Ed.) (2009) Intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo Chapter 2, p. 33. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag.

- ↑ Gottwik, G. (Ed.) (2009) Intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo. Chapter 2. Heidelberg: Springer Medicine Verlag.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (2000). Intensive short-term psychotherapy - Central Dynamic Sequence: Phase of Pressure. In H. Davanloo, Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD. New York: Wiley. (pp. 183-208).

- ↑ Gottwik, G. (Ed.) (2009) Intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo. Chapter 3. Heidelberg: Springer Medicine Verlag.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (2000). Intensive short-term psychotherapy - Central Dynamic Sequence: Phase of Challenge. In H. Davanloo, Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD. New York: Wiley & Sons (pp. 209-234)

- ↑ Gottwik, G. (Ed.) (2009). Intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo , Chapter 3. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag.

- ↑ Gottwik, G. (Ed.) (2009) Intensive psychodynamic short-term therapy according to Davanloo , Chapter 5, p. 64 ff. Heidelberg: Springer Medizin Verlag.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (2001) Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Extended Major Direct Access to the Unconscious. European Psychotherapy, vol 2 no 2, 37 ff.

- ↑ Davanloo, H. (2000). Intensive short-term psychotherapy - Central Dynamic Sequence: Head-On Collision with Resistance. In H. Davanloo, Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy: Selected papers of Habib Davanloo, MD. New York: Wiley. (pp. 235-253)

- ^ Letter psychotherapy of personality disorders . In: J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. . 179, No. 4, April 1991, pp. 188-93. PMID 2007888 .

- ^ Short-term psychotherapy of personality disorders . In: Am J Psychiatry . 151, No. 2, February 1994, pp. 190-4. PMID 8296887 .

- ^ A randomized prospective study comparing supportive and dynamic therapies. Outcome and alliance . In: J Psychother Pract Res . 7, No. 4, 1998, pp. 261-71. PMID 9752637 .

- ^ Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy for DSM-IV personality disorders: a randomized controlled trial . In: J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. . 196, No. 3, March 2008, pp. 211-6. doi : 10.1097 / NMD.0b013e3181662ff0 . PMID 18340256 .

- ↑ Short-Term Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Personality Disorders: A critical review of randomized controlled trials . In: J. Pers. Disord. . 25, No. 6, December 2011, pp. 723-40. doi : 10.1521 / pedi.2011.25.6.723 . PMID 22217220 .

- ^ Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy of treatment-resistant depression: a pilot study . In: Depress Anxiety . 23, No. 7, 2006, pp. 449-52. doi : 10.1002 / da.20203 . PMID 16845654 .

- ^ Short-term dynamic psychotherapies in the treatment of major depression . In: Can J Psychiatry . 47, No. 2, March 2002, p. 193; author reply 193-4. PMID 11926082 .

- ^ The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depressive disorders with comorbid personality disorder . In: Psychiatry . 74, No. 1, 2011, pp. 58-71. doi : 10.1521 / psyc.2011.74.1.58 . PMID 21463171 .

- ^ The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: a summary of recent findings . In: Acta Psychiatr Scand . 121, No. 5, May 2010, p. 398; author reply 398-9. doi : 10.1111 / j.1600-0447.2009.01526.x . PMID 20064127 .

- ^ The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis . In: Clin Psychol Rev . 30, No. 1, February 2010, pp. 25-36. doi : 10.1016 / j.cpr.2009.09.003 . PMID 19766369 .

- ↑ Does brief dynamic psychotherapy reduce the relapse rate of panic disorder? . In: Arch. Gen. Psychiatry . 53, No. 8, August 1996, pp. 689-94. doi : 10.1001 / archpsyc.1996.01830080041008 . PMID 8694682 .

- ↑ Direct diagnosis and management of emotional factors in chronic headache patients . In: Cephalalgia . 28, No. 12, December 2008, pp. 1305-14. doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2008.01680.x . PMID 18771494 .

- ↑ Direct diagnosis and management of emotional factors in chronic headache patients . In: Cephalalgia . 28, No. 12, December 2008, pp. 1305-14. doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2008.01680.x . PMID 18771494 .

- ^ Single-blind clinical trial of psychotherapy for treatment of psychogenic movement disorders . In: Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. . 12, No. 3, April 2006, pp. 177-80. doi : 10.1016 / j.parkreldis.2005.10.006 . PMID 16364676 .

- ↑ Intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy to reduce rates of emergency department return visits for patients with medically unexplained symptoms: preliminary evidence from a pre-post intervention study . In: CJEM . 11, No. 6, November 2009, pp. 529-34. PMID 19922712 .

- ^ Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for somatic disorders. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials . In: Psychother Psychosom . 78, No. 5, 2009, pp. 265-74. doi : 10.1159 / 000228247 . PMID 19602915 .

- ↑ Somatization: Diagnosing it sooner through emotion-focused interviewing . In: J Fam Pract . 54, No. 3, March 2005, pp. 231-9, 243. PMID 15755376 .

- ↑ Intensive Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy in a private psychiatric office: clinical and cost effectiveness . In: Am J Psychother . 56, No. 2, 2002, pp. 225-32. PMID 12125299 .

- ^ Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapies for common mental disorders . In: Cochrane Database Syst Rev . No. 4, 2006, p. CD004687. doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD004687.pub3 . PMID 17054212 .

- ^ Kandel, Eric R. In Search of Memory. New York: WW Norton & Company, 2006; pp.369-370.