Intercomprehension (learning method)

Intercomprehension is the understanding of languages that are neither naturally acquired nor learned through class.

overview

Adult German speakers usually understand the Dutch sentence “Typ voor local en regional informatie een plaatsnaam of de vier cijfers van een postcode en klik op OK” (German: “Tip for local and regional information a place name (place name) from the four digits of a postal code (zip code) [ein] and click on OK “. The identification of the target language elements provides important information on the vocabulary and grammar of Dutch, but also so-called correspondence rules between the target and the source language, such as voor ('for'), een ('a'), plaatsnaam ('place name') and postcode ('zip code'), for word formation, such as Dutch -atie (for German '-ation') etc., for phonetics and orthography (long vowels are in Dutch marked by doubling, as in voor and naam ), morphology (the plural is expressed, among other things, by - s - as is often the case in English and French), the imperative is similar to d em German pattern ( type 'tip (e)'). At the same time open-ended questions that require a later clarification stay (Does of really, from 'or or'?).

The knowledge of an inter-lingual correspondence rule leads to an expansion of knowledge with some practice: Once voor has been identified, then voor niks ~ for nothing (free), wat voor - what for (what for; what for) become immediately transparent. The interlingual recording is easily expanded to include an “ auto- input” on the learner's side , which is created by thinking about the target language, its characteristics and also its relationship to the source language. In this context, one has also spoken of optimized input ( enhanced input ). As the examples reveal, intercomprehension not only requires sensitivity for languages, but also for the actual intercomprehension action or the learning process. Mental processes such as those described here develop routines in a short time, so that the intercomprehensive approach also describes a practice of approaching new foreign languages and expanding knowledge in already known languages. This explains why the intercomprehensive approach should be an effective strategy for raising language awareness and language learning competence.

Intercomprehension and multilingualism promotion from a European and international perspective

The fact that intercomprehension enables the rapid development of reading skills in other foreign languages than those already learned explains the special interest of the European Union in intercomprehension and its didactics (Bär 2004). The recommendations for the development of language curricula say : “… making it possible for learners to acquire partial competences in languages related to those they know or have studied already (eg intercomprehension)” (Beacco et al. 2010).

In the Romanic countries, intercomprehension is widely recognized - Union Latine, Redinter, Euro-mania, InterRom, InterLat, Galanet and others. a. m. (passim Capucho et al. 2007; Meißner et al. 2011). In Germany, the approach was funded by EuroCom .

The intercomprehension didactics developed in Europe is now also attracting attention in the context of American indigenous multilingualism (Romani 2010). This applies to research (Meißner 2010) as well as material development and a large number of projects. Since intercomprehension facilitates the conversation between people of different languages and allows the reading of texts from many languages, it has a strong connection to intercultural learning, as it is e.g. B. in projects of media-supported interpersonal encounter learning (Degache 2003). Reading several languages and being able to communicate with people of different languages (by being able to follow them in their languages) leads to a significant increase in intercultural experience and intercultural competence.

Romansh or Slavic intercomprehension is also available to German speakers if they have the appropriate knowledge. These can be considered to be available if level B1 is achieved in two foreign languages . This statement should be relativized insofar as empirical research repeatedly shows that children are already thinking about language and comparing linguistic structures with one another. In this way they recognize z. B. grammatical regularities. Intercomprehension is thus a method for the rapid expansion of multilingualism in more than two foreign languages. If you want to establish broad-based intercomprehension skills, a diversified range of school languages and reflective foreign language lessons are indispensable. In the German-speaking area, EuroCom in particular is committed to the “Eurocomprehension” concept.

Experience with intercomprehension teaching and intercomprehensively based learning

As the Dutch-German example illustrates, the intercomprehension corresponds to the mental language processing as it is common in understanding linguistic data or in language acquisition. This is not surprising, because intercomprehension is nothing more than comprehension between linguistic varieties, e.g. B. between dialects of one's own language. Comprehension is always based on the spontaneous or inferred identification of linguistic schemes, i. H. on the return of incoming language patterns (words, structures, etc.) to already available knowledge, which in turn can cause the construction of new knowledge schemes. Network models for the multilingual mental lexicon explain such processes particularly plausibly. Because of its naturalness, intercomprehension leads to very rapid language growth. The material prerequisite, however, is always that sufficient transfer bases can be found between the languages in question . This is to be understood as similarities and analogies between known schemes and new knowledge objects ( e.g. German typing ~ nl. Type ). While a large number of lingual similarities are evident between the languages of the same language family, there are largely no similarities between distant languages (e.g. German and Japanese ). In these cases, the intercomprehension didactics developed in the meantime does not apply.

In contrast to foreign language teaching in schools, the efficiency of which has only recently begun to be empirically measured, intercomprehension didactics has endeavored to provide a transparent empirical foundation since its inception (Meißner 1993; Hufeisen 1994) and has presented a number of studies (including Meißner & Burk 2001; Bär 2009; Strathmann 2010; passim Doyé & Meißner 2010; Meißner et al. 2011, Morkötter 2016). All of these empirical studies, which are mentioned here only to a small extent, and which are joined by numerous foreign studies, support the well-known positive experience with intercomprehension (cf. passim Meißner & Reinfried 1998). That the Interkomprehensionsereignis building the learner language or interlanguage or the multilingual mental lexicon in the nascent state maps and that this happens bewusstheitsnah, the particular suitability explains Interkomprehensionsmethode to promote language learning awareness ( language and language learning awareness raising strategy ) (Meissner & Morkötter 2009) and language learning skills. There is a close relationship here between the intercomprehension method (Meißner 2004a; Hufeisen et al., Rieder 2001, also Doyé 2005) and learner autonomy .

The extended transfer type and the hypothesis grammar

As already mentioned, the intercomprehension didactics is a transfer didactics. The sciences of learning generally understand transfer to be the “influence of a material already learned on (the) learning of a subsequent material (learning material, task)” (Heuser 2001: IV, 335). However, from the point of view of language acquisition research, this definition falls short if it is limited to teaching situations (as is customary in foreign language didactics), because transfer processes are obviously more or less involved in every language acquisition and every language encounter - whether controlled or uncontrolled. This is evidenced by phenomena such as recognition and the frequency with which forms are processed or the expansion of semantic and functional schemes. In this context, the mental activities of accretion, structuring and tuning (Norman 1982) were mentioned several times . This concerns the encounter with new linguistic structures, their structuring and their fitting into the (multilingual) mental lexicon of the language participants (Meißner 2004c; Müller-Lancé 2019). Since the goal of intercomprehension didactics is first of all to transform the learner's existing learning-relevant 'sluggish prior knowledge' into useful language acquisition and language knowledge, research in intercomprehension didactics had to shed light on the relationships between the various fields of application of linguistic transfer and its mental organization. The data collected in connection with the project 'German speakers read unknown Romance foreign languages' (Meißner 2013) allowed the creation of a transfer type that goes far beyond the sometimes learning-inhibiting distinction between positive and negative transfer (Meißner 2004b).

- Transfer type:

- Identification transfer: reading comprehension, listening comprehension, listening comprehension

- Production transfer: writing, reading

- Transfer direction:

- proactive transfer: from an already known language to the target language

- retroactive transfer: from the target language back to an already known language with modification effects in the mental structure of the bridge language

- Transfer range:

- Intralingual transfer: within a single target language system, e.g. B. L4 Italian or the native language

- Intralingual transfer: within a source-language system, e.g. B. the mother tongue or a language already known to a learner

- Transfer interlingual: between languages, concerning a certain systematicity / regularity, which includes at least two languages.

- Transfer areas of the languages involved

- lexical transfer

- morphosyntactic transfer

- phonological transfer

- orthographic transfer

- pragmatic transfer, transfer of communicative attitudes, routines, etc.

- Transfer categories:

- Form transfer: Transfer of signifiers or form elements (e.g. morphemes, word formation patterns) etc.

- Content transfer, e.g. B. Transfer of semantic schemes, additions of interlingual 'polysemy' or intersynonymy.

- Function transfer: Transfer of linguistic (grammatical) regularities

- didactic transfer:

- Transfer of learning experiences. Affects self-regulation and learning Monitoring: Motivational control; Learning time management; Organization of the learning environment; definition of learning objectives and learning paths; Evaluation and control of the learning steps and the learning success; Securing learning outcomes; Use and availability of media and resources; Organization of social components of successful learning e.g. B. in contact with other people: tandem and exchange of language and learning experiences; Use of learning counseling; Creation of a learning protocol; a personal multilingual dictionary; Protocol and systematic updating of the hypothesis grammar; Organization of learning strategies and techniques; Selection and competent use of aids such as consultation grammars and dictionaries and, last but not least, separation of the lexical and morphosyntactic material into the categories 'opaque' and 'transparent', creation of your own learning plan based on the hypothesis grammar and learning monitoring.

A success-determining variable concerns the trigger of a transfer, i. i. the assignment of phenomena in different languages under the criterion of a real or only apparent similarity. Linguistic sensitivity and sensitivity for goal-oriented intercomprehension processes are decisive for the initiation of transfer actions of various kinds.

To explain one of the central elements of intercomprehension didactics in addition to the transfer, the grammar of hypotheses, the Dutch example should be recalled: The identification processes described generate 'language hypotheses' that focus on the construction of a basic grammar of the target language and its vocabulary by the learners themselves, and one Need to be checked later (“Do you really form the plural with –s?”): In the social game of natural language acquisition, the direct and indirect reactions of the language partners have a confirming or rejecting effect on the formation and modification of the hypotheses. Significant differences compared to the acquisition of the first language result from the high degree of potentially learning-relevant, often multilingual, prior knowledge of the learners. Adults already have at least one developed language system (their first language) and also very often have knowledge of several foreign languages relevant to learning and how they can be acquired. They use this knowledge if they want to approach another language or if they want to deepen their knowledge of a certain foreign language. So concern z. For example, in Italian folk high school, well over half of all vocabulary questions are inter-lingual similarities (“Does the word mean the same as in French?”) (De Florio-Hansen 1994). The use of hypothesis grammar is a decisive criterion for the quality of intercomprehension didactic teaching. The hypothesis grammar is not only a means of developing the target language, but also to ensure sustainability. Only the interaction of volitional (motivational) components ( savoir-être ) with those of knowledge ( savoir ) and ability ( savoir-faire ) - to put it in the terminology of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learn - teach - assess ( Council of Europe 2001) - allow the development of an operable intercomprehension competence (cf. also REPA 2009).

Selection and arrangement of the linguistic input

Obviously, in order to be able to really use their (latently already existing) intercomprehension potential, learners must be able to identify transfer bases in sufficient numbers. This starts with the vocabulary. The critical threshold is around 30 percent of the types , with the number of words ( tokens ) initially being of secondary importance. This underlines both the long-term structure of the intake and the arrangement of the input. Since intercomprehension is a natural phenomenon that encompasses processes that are already encountered in the first language acquisition, intercomprehensive procedures can be used at an early stage in language acquisition (Imgrund 2007; Morkötter 2011).

As with language learning in general, elements that are 'central' (often) for a language must be separated from 'eccentric' (seldom). Due to its size, this primarily concerns the so-called basic vocabulary. The following graphic shows the percentage of recognition rates between the basic vocabulary of the most important German foreign school languages, computed from the corresponding lists of the company KLETT:

As you can see, 81.5% are z. B. the Spanish, 86% of the Italian, 70% of the English basic vocabulary on the basis of French already 'identifiable, but English' helps', to the extent of 55% for French (Meißner 1989). One can argue about the subtleties of computation and the presence of the basic vocabulary in different types of text, but the extremely high rate of transfer bases within the respective Romance, Slavic or Germanic language family cannot be in doubt. Computer lexicography has put lexical frequency research on a new basis by expanding the breadth of the material to millions and millions of tokens. This allowed the development of the so-called core vocabulary of Romansh multilingualism and the construction of corresponding learning apps. Computer-aided lexicometric research leads to a reliable identification of vocabulary according to the criteria of inter-comprehension didactically relevant criteria of interlingual transparency (such as: German nation, en./fr . Nation, it. Nazione, rus. На́ция , nl. Natie etc.) and opacity ( German broom , fr. ba lai, en. broom , sp. escobón , pt. vassoura , etc.). The measurement of the Romansh core vocabulary offers new addressee-specific bases for the selection of the input, e.g. E.g. the acquisition of the lexical transfer bases necessary for intercomprehension is greatly facilitated (Meißner 2018; Reissner 2019).

Obviously the languages of the individual language families differ in the degree of their intercomprehensibility. Romance languages are generally considered to be relatively easily intercomprehensively sensitive to one another. Between Danish, Norwegian ( Bokmål and Nynorsk ) and Swedish, intercomprehensively based communication is traditionally common (Braunmüller 2019); Between the German and the Scandinavian sister languages, however, the intercomprehension requires a significantly greater effort (Zeevaert & Möller 2011).

German itself also has broad bridges to the Romance languages. These primarily deliver foreign words: progressive, graceful, liberal, human, medicine, animal, consumption, radio, maritime, stellar, hospital, enthusiasm, enthousiasme, enthusiasm, entusiasmo, police, police, polizia, polizija . Such cognates represent a high percentage of so-called transfer bases in theory-oriented texts (newspaper articles, technical languages, news) after the structural words. Studies on Romance intercomprehension among German speakers have shown that, in addition to their knowledge of foreign languages, they often make strong use of German educational vocabulary for a transfer of identification.

The idea of language filtering goes back to Klein & Stegmann (1999): In the Seven Seven they organize the Romance material - vocabulary, morphology, phonetics and phonology, syntax - according to transfer and 'profile forms'. By the latter, they understand forms and functions that can only be found in a single Romance language and therefore do not represent any transfer bases: for example fr. beaucoup in the series it. molto , pg. muito , sp. mucho , en. much , sp. alfombra in pg. wallpaper , cat. catifa , it. tappeto , German carpet , fr. tapis , en. carpet etc .; in the area of time formation, kat. Pretèrit perfet perifràstic , formed with a conjugated form of the verb anar (dt. To go) <Latin. VADERE ( vaig, vas, va, vam / vàrem, vau / vàreu, van / varen + infinitive) an example. The interlingual economy of learning is particularly evident in the field of interlingual phonetic rules. In this way, knowing about the regularity of graphic correspondence creates it. -tt-, sp. -ch-, pg. -it-, fr. -it-, rum. -pt- Transparency between numerous word series: such as notte, noche, noite, nuit, nocte or otto, ocho, oite, huit, opt or perfetto, perfecto, perfeito, parfait, perfect , dt. perfect . In the Spanish-Italian comparison alone, this leads to numerous other identifications, including sospecho / sospetto, dicho / detto; satisfecho / sodisfatto, derecho / diritto, pecho / petto, lucha / lotta, techo / tetto, estrecho / stretto, lecho / letto . In essence, the message is: Instead of learning a huge number of individual language words and rules, use a manageable number of transfer rules to understand the vocabulary of several languages. It is obvious that learners - in order to be able to do this successfully - have to get to know the profile forms at a very early point in the learning path. The creation of the lexical database of the core vocabulary of Romance multilingualism enables the identification of so-called interligalexes. The word describes the core element on which a transparent interlingual series is based. Knowledge of the AC (C) ID- strain leads to the identification of en./fr. accident , it. accidente , pt. acidente , sp. accidente , pt. acidentalmente ..., en. accidental ..., technically also related to Akzidens, rus . акциде́нция, pol. akcydens etc. The interligalexical analysis allows, in particular, the construction of corresponding exercises for the identification and memorization of interphonological regularities or form-congruent lexical series (type: molto , pg. muito , sp. mucho , en. much ).

Oral versus written form in intercomprehension

The explanations so far have been based primarily on the interlingual identification of lexemes and grammatical phenomena in their graphic presentation. It was, so to speak, 'suppressed' that listening comprehension processes run very differently than those of reading comprehension. However, it is not just a question of different mental processes, but also of completely different linguistic sign forms - acoustic or visual - that have to be processed. If one uses the transcription, one can see - graphically - the difference between en. wire and en. / 'waiə /, heavy and /' hɛvi / at a glance. It should be noted that the mental processing of a read transcribed word differs fundamentally from the auditory processing of the same. The approximation of the spelling to a standardized pronunciation pattern (transcription) is in this sense a kind of crutch that made it possible to get an idea of the pronunciation ('speak') based on the spelling. This was didactically necessary as long as there were no media that 'transmitted' the spoken language and brought it to the ear. This short remark methodically requires separate access to the 'speak' and the 'write'. Intercomprehensive listening comprehension of a 'foreign' target language combines with all phenomena that are relevant in the didactics of listening comprehension.

Listening comprehension always takes place in a narrow time window - definitely u. a. through the speed of speech and the linearity of speech - instead. So there is almost no time to think about linguistic structures. Analyzes of listening comprehension processes in foreign but somewhat intercomprehensible languages consistently show that listeners extract content-related features from the flow of speech and (re) construct the content of a text on this basis. Analyzes of listening comprehension processes and results of Romanophones with unknown Romance target languages have clearly shown which phonological and phonetic features are 'difficult' to understand (passim: Meißner & Burk 2001; Jamet 2007; numerous new studies are available). It should be noted that the results of these studies and their methodological implications were neither used in German-language research on listening comprehension nor in the practice of foreign language teaching.

Methodically, it can be deduced from this mixture that exercises for intercomprehensible listening comprehension can only be used if the learner is familiar with a sufficient vocabulary repertoire.

Reflexive learning and intercomprehension

The range of the use of intercomprehensive procedures is considerable: it ranges from the simultaneous acquisition of reading competence in several languages of the same language family to the control of tertiary language teaching through systematic activation of the learner's existing transfer-relevant prior knowledge (e.g. learning Spanish to French). And, of course, intercomprehensive procedures can also be used in some areas when learning distant languages (German / Polish or Russian) (Behr 2005); they can also enrich and improve traditional foreign language teaching and its management.

The advantages of the intercomprehensive method for the reflexive learning of languages and learner autonomization can be summarized on the basis of experience documented so far (case studies, laboratory studies):

- Interkomprehension works very closely and consciously with linguistic structures and therefore gives learners insight into the structure of their own learner language. For teachers, it is an important element of learning diagnostics.

- Interkomprehension teaches / practices the goal-oriented comparison between languages and is a strategy for promoting language awareness.

- As intercomprehension provides sensitivity to linguistic structures and functions by comparing languages, it represents a strong strategy for preventing errors.

- Since the intercomprehension method requires the long-term recording of the hypothesis grammar, it promotes learning monitoring and the development of learning routines that generate sustainability.

- The examination of the hypothesis grammar requires the consultation of suitable media: of glossaries, concordances, dictionaries, consultation grammars on paper or electronic data carriers.

Last but not least:

- Successful intercomprehension strengthens self-efficacy and leads to a revision (positiveization) of previous ideas about foreign languages and their learnability. The multilingual experience associated with intercomprehension makes one aware that languages support one another and make language learning easier in general.

Text work and language curriculum in intercomprehension didactics

As it became clear, there is a close connection between intercomprehension didactic methods and learner autonomy through hypothesis-generating methods.

In the discussion about constructivist learning, the advantages of unstructured learning were emphasized several times. They are seen in the fact that learners themselves have to deconstruct and reconstruct texts, which leads to a deep and broad processing of the linguistic data. This also applies to intercomprehensive reading (Lutjeharms 2002; 2019). That is why texts should not - as is usual with strongly inductivistic control - emphasize the phenomenon to be learned excessively and thereby prevent deconstruction and reconstruction. Basically, the order in which the learners themselves perceive the linguistic topics (nouns, pronouns, etc.) determines the progression. Intercomprehension didactics can take advantage of what is known as 'authentic' text reading right from the start.

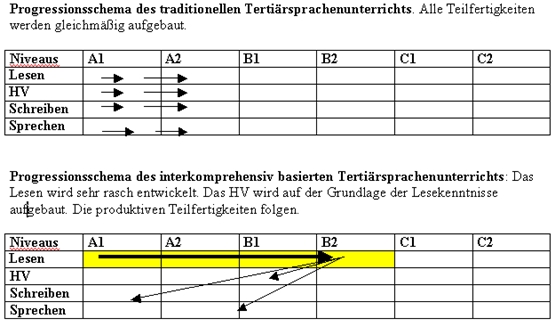

If intercomprehension didactic procedures are used in the teaching of a third modern foreign language (e.g. Italian / Spanish after English, French), then the question must be asked how the language curriculum should be structured. If the progression pattern follows that of the first and second foreign language, this means that receptive competencies, which are many times larger than productive competences, cannot be used, as the following schemes show:

A progression that relies heavily on the already latent reading competence in the target language at the beginning of the course results in considerably more processing of texts and language data than is the case according to the traditional pattern. With the expansion of the input and a corresponding control, the intake increases. This in turn gives the opportunity to add new input to the existing knowledge and to expand multilingual knowledge (see Morkötter 2019; Lutjeharms 2019).

All of this in turn enables a better quality of intercultural learning, since the understanding of target cultural topics in the target language plays an important role in the development of intercultural competence.

The structure of the progression is then divided into the following phases: Introducing the target language phonetics and pronunciation (the learners need basic knowledge of the pronunciation of the target language orthography), developing the target language basic grammar by creating a hypothesis grammar - promoting the development of productive skills (if desired ). Of course, this ideal-typical progression can be broken if the learners so wish; z. B. by demanding more productivity.

The intercomprehensive approach internationally in teaching and research

Although the European Union has pointed out the advantages of the intercomprehensive approach in numerous documents in connection with the definition of the "multilingual minimus" - as many citizens as possible should acquire operable knowledge of at least two foreign languages in addition to their mother tongue - (cf. Beacco et al . 2010; 2016), foreign language teaching is generally far from passing on the benefits of this approach to learners. After all, the first signs of opening up English teaching are recognizable (Jakisch 2019) and French and Spanish didactics have also presented intercomprehension didactics in several publications and magazine articles. Corresponding teaching materials are also available.

That intercomprehension is combined with an expansion of the communicative radius of a target language - knowledge of Italian e.g. B. open the way to around 65 million native speakers; Understanding the other large Romance language communities through knowledge of Italian leads to reading comprehension of the languages of around 850 to 900 million native speakers - it has political and economic weight: Romansh speakers find it particularly easy to expand the communicative radius offered here, and the intercomprehensive approach has the advantage of enabling its population to acquire Romansh multilingualism at a very affordable price. With Italian (French, Portuguese, etc.) as a foreign language, the intercomprehension method increases its attractiveness on the international language market. For German as a foreign language the situation is completely different, for English as an International Language (EIL). As for German as a bridge language to the other Germanic languages, its use is due to a comparatively low interest in so-called 'small' target languages such as Danish (5 million native speakers), Norwegian (4.3) and Swedish (10.5 ) limited. All the more interest is German as a foreign language after English, as developed by Hufeisen (cf. 1994). The German-speaking Dutch didactics have long been using inter-lingual transfer bases. A systematic language policy promotion of Slavic intercomprehension has so far hardly been promoted by the corresponding states, although the potential advantages of such have long been recognizable. For the German-speaking area, Tafel et al. (2009) presented a corresponding linguistic description of the slavs and their interlingual transfer bases (also Mehlhorn 2019).

It can be assumed that the respective language policy context is not without consequences for the promotion of intercomprehension teaching and intercomprehension research. It is no coincidence that the Romansh countries in particular have promoted understanding and intercomprehensive learning of the Romance sister languages through numerous organizations and projects, both European and Latin American. In research, this is reflected in more than a hundred qualification theses - in dissertations and habilitation theses alone.

In German-speaking countries, the explicit use of intercomprehensive approaches begins with the lesson descriptions by Abel (e.g. 1971). The approach, supported by the desire for a cross-language learning economy, is in practice much older and, in essence, can be proven centuries ago. In connection with the existing language policy concepts (including Bertrand & Christ 1990), both processes for Romance intercomprehension among German speakers and the possibilities of their teaching use between 1994 and 2018 at the Giessen Chair for the Didactics of Romance Languages were researched and analyzed in a large number of case studies (Meißner 1993; 2011).

Conclusion

In the light of previous experience and empirical studies on intercomprehension in different learning contexts, the intercomprehension method must be viewed as a way to improve the quality of language learning. The primary reason is that it is a powerful language learning awareness strategy. As intercomprehension makes the structure of the learner language aware of the structure of the learner's language through the presentation of the hypothesis grammar, it can be considered an important tool in learning diagnostics. Intercomprehension does not only concern the so-called late-learned foreign languages (cf. Meißner & Tesch 2010) and the teaching of Romance languages (Zybatow 2002; Hufeisen & Lutjeharms 2007). Rather, young learners should also be given a suitable insight into their own language growth. All previous experiences with intercomprehension or intercomprehension-based teaching show that the learners

- develop high reading skills in the target language very quickly and thus be able to use more input

- learn to compare languages

- develop their ability to learn reflexively

- optimize their previous attitudes towards languages and their experiences of self-efficacy with languages.

However, reflexive learning also requires reflexive teaching. It is characterized by the fact that the learners are included in the decisions and that their learning processes are also analyzed and discussed in the classroom.

literature

- Abel, Fritz (1971): The teaching of passive Spanish and Italian skills in the context of French lessons. The Newer Languages 70, pp. 355–359.

- Bär, Marcus (2004): European multilingualism through receptive skills: Consequences for educational policy . Aachen: Shaker.

- Bär, Marcus (2009): Promotion of multilingualism and learning skills. Case studies on intercomprehension classes with students in grades 8 to 10 . Tübingen: Fool.

- Beacco, Jean-Claude, Byram, Michael. Cavalli, Marisa. Coste, Daniel. Egli Cuenat, Mirjam. Goullier, Francis et Panthier, Johanna (2010): Guide pour le développement et la mise en œuvre de curriculums pour une éducation plurilingue et interculturelle . Strasbourg: Conseil de l'Europe. (www.coe.int/lang/fr).

- Behr, Ursula (2005): Cross-lingual learning in Russian lessons - how does it work? Practice Foreign Language Instruction, 5/05, pp. 43–48.

- Bertrand, Yves & Christ, Herbert (Red.) (1990): Suggestions for an extended foreign language teaching. New language messages 43, pp. 208-212.

- Braunmüller, Kurt (2019): Natural intercomprehension using the example of Scandinavia. In: Fäcke & Meißner (ed.), Pp. 300–303.

- Capucho, Filomena. lves de Paula Martins, Adriana. Degache, Christian & Tost, Manuel (eds.): Diálogos em intercompreensão . Lisboa: Universidade Católica Editora.

- De Florio-Hansen, Ines (1994): From talking about words. Vocabulary explanations in Italian lessons with adults . Tübingen: Fool.

- Degache, Christian (2003): Romance cross-comprehension and language teaching: a new trend towards linguistic integration in Europe. The Galanet project solution. In: Communications presented at The International Conference. Teaching and learning in higher education: new trends and innovations. Universidade de Aveiro (Portugal), 13.-17. April 2003.

- Doyé, Peter (2005): Intercomprehension. Reference study. Preface by Jean-Claude Beacco & Michael Byram. Language Policy Division. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Doyé, Peter & Meißner, Franz-Joseph (eds.) (2010): Lernerautonomie durch Interkomprehension: Projects and Perspektiven / Promoting Learner Autonomy through intercomprehension: projects and perspectives / L'autonomisation de l'apprenant par l'intercompréhension: projets et perspectives . Tübingen: Fool.

- Fäcke, Christiane & Meißner, Franz-Joseph (Ed.) (2019): Handbook of Multilingualism and Multiculturalism . Tübingen: Fool.

- Heuser, Herbert (2001): Transfer. In: Lexicon of Psychology in five volumes. Heidelberg / B Berlin: Spectrum, 335.

- Hufeisen, Britta (1994): English in German as a Foreign Language. Munich: Ed. Velcro.

- Horseshoe, Britta (2003): L1, L2, L3, L4, Lx - all the same? Linguistic, internal and external learner factors in models for multiple language acquisition. In: Baumgarten, Nicole. Böttger, Claudia. Moltz, Markus & Probst, Julia (eds.): Translation, intercultural communication, language acquisition and language teaching - living with several languages. Festschrift for Juliane House on her 60th birthday. Bochum: AKS, pp. 96-108.

- Horseshoe, Britta & Marx, Nicola (20076): EuroComGerm - The Seven Sieves : Being able to read Germanic languages. Aachen: Shaker.

- Imgrund, Bettina (2007): Multilingual didactics and its application in linguistic beginners lessons. Results of a development project SEEW of the PHZ Zug. Babylonia 07/3, pp. 49-57.

- Jakisch, Jenny (2019): Procedure for promoting multilingualism in English lessons. In: Fäcke & Meißner (ed.), Pp. 459–464.

- Jamet, Marie-Christine (2007): A l'écoute du français. The oral assessment in the cadre de l'intercompréhension des langues romanes . Tübingen: Fool.

- Kischel, Gerhard (Ed.): EuroCom - Multilingual Europe through intercomprehension in language families. Proceedings of the international specialist congress on the European Year of Languages 2001. Hagen, 9. – 10. November 2001. Aachen: Shaker

- Klein, Horst G. & Stegmann, Tilbert D. (1999): EurocomRom. The seven sieves. Read Romance languages immediately. Aachen: Shaker.

- Lutjeharms, Madeline (2002): Reading strategies and intercomprehension in language families. In: Kischel (Ed.), Pp. 124–140.

- Lutjeharms, Madeline (2019): Intercomprehension and language skills. In: Fäcke & Meißner (Ed.), Pp. 325–329.

- Mehlhorn, Grit: teaching Slavic intercomprehension. In: Fäcke & Meißner (ed.), Pp. 397–401.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (1989): Basic vocabulary and language sequence. A statistical quantification on lexical transfer: English / French, French / English, Spanish, Italian. French today 20, pp. 377–387.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (1993): Outlines of the didactics of multilingualism. In: Bredella, Lothar (Hrsg.) (1995): Understanding and understanding through language learning. Files of the 15th Congress for Foreign Language Didactics of the German Society for Foreign Language Research, Giessen 4. – 6. October 1993. Bochum: Brockmeyer, pp. 173-187.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (2004a): Introduction à la didactique de l'eurocompréhension. In: Meißner, Franz-Joseph. Meissner, Claude. Klein, Horst G. & Stegmann, Tilbert D. (2004): EuroComRom - les sept tamis. Lire les langues romanes dès le départ. Aix-la-Chapelle: Shaker, pp. 7-140.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (2004b): Transfer and Transfer. Instructions for intercomprehension classes. In: Klein, Horst G. & Rutke, Dorothea (Ed.): Newer research on European intercomprehension. Aachen: Shaker, pp. 39-66.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (2004c): Modeling plurilingual processing and language growth between intercomprehensive languages . In: Zybatow, Lew N. (ed.): Translation in the global world and new ways in language and translator training . (Innsbruck lecture series on translation studies II). Frankfurt a. M .: Peter Lang, pp. 31-57.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (2010): 86. Intercomprehension research. In: Königs, Frank G. & Hallet, Wolfgang (Hrsg.): Handbuch Fremdsprachendidaktik. Seelze: Kallmeyer / Klett, pp. 381–386.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (2011): Intercomprehension between distant languages: language policy, learning and teaching, learner autonomy. Revista de intercompreensão, pp. 157-186.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (2011b): La didáctica de la intercomprensión y sus repercusiones sobre la enseñanza de lenguas: el ejemplo alemán. In: Synergies Chili 6/2011, p. 59-70.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph (2018): The measurement of the core vocabulary of Romance multilingualism. A didactic analysis for interlingual transparency and frequency research . GiF: on 12 .

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph & Burk, Heike (2001): Listening comprehension in an unknown Romance foreign language and methodological implications for tertiary language acquisition. Journal for Foreign Language Research 12 (1), pp. 63-102.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph & Morkötter, Steffi (2009): Promotion of metalinguistic and metacognitive competence through intercomprehension. In: Raupach, Manfred (Coord.): Strategies in foreign language teaching. Foreign languages teaching and learning 38, pp. 51–69.

- Meissner, Franz-Joseph. Capucho, Filomena. Degache, Christian. Martins, Adriana. Spita, Doina & Tost, Manuel (coord.) (2011): Intercomprehension: Learning, teaching, research. Apprentissage, enseignement, research. Learning, teaching, research. Tübingen: Narr Verlag.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph & Reinfried, Marcus (Eds.) (1998): Mehrsprachigkeitsdidaktik. Concepts, analyzes, teaching experience with Romance foreign languages. Tübingen: Fool.

- Meißner, Franz-Joseph & Tesch, Bernd (Hrsg.) (2010): Teaching Spanish skills-oriented. Seelze: Klett / Kallmeyer.

- Morkötter, Steffi (2011): Early intercomprehension at the beginning of secondary school. In: Baur, Ruprecht & Hufeisen, Britta (Ed.): Much is very similar. Individual and social multilingualism as an educational policy task. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren.

- Morkötter, Steffi (2019): Intercomprehension and transfer. In: Fäcke & Meißner (Ed.), Pp. 321-324.

- Müller-Lancé, Johannes (2019): Modeling of intercomprehension processes. In: Fäcke & Meißner (eds.), 316-320.

- Norman, Donald A. (1982): Learning and Memory. San Francisco: Freeman.

- REPA = Candelier, Michel. Camilleri-Grima, Antoinette. Castellotti, Véronique. de Pietro, Jean-François. Lorincz, Ildiko. Meissner, Franz-Joseph. Schröder-Sura, Anna. Noguerol, Artur & Molinié, Muriel (2009): Framework of Reference for Plural Approaches to Languages and Cultures. (July 2009. Graz: CELV / Strasbourg: Council of Europe.).

- Reissner, Christina (2019): Material basics of Romance multilingualism. In: Fäcke & Meißner (ed.), Pp. 333–339.

- Rieder, Karl (2001): Intercomprehension. Decipher foreign language texts. Vienna: Austrian Federal Publishing House.

- Romani Miranda, Maggie (2011): Identidad lingüística e Intercomprensión en el Perú: la enseñanza / aprendizaje de lenguas en aulas multilingües en Amazonía. Synergies Pays germaniques 4, pp. 29-46.

- Strathmann, Jochen (2010): Spanish through Intercomprehension: Multimedia Language Acquisition Processes in Foreign Language Classes. Aachen: Shaker.

- Tafel, Karin. Durić, Rašid. Lemmen, Radka. Olshevska, Anna & Przyborowska-Stolz, Agata: Slavic Intercomprehension - An Introduction (eBook). Tübingen: Narr & Francke Attempto.

- Zeevaert, Ludger & Möller, Robert (2011): Ways, wrong ways and wrong ways in text indexing - empirical studies on Germanic intercomprehension. In: Meißner et al. (Ed.), Pp. 146-163.

- Zybatow, Lew N. (2002): The Slavic Eurocomprehension Research and EuroComSlav. In: Kischel (Ed.), Pp. 357–371.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The French version is even clearer: “… l'organization de cours“ plurilingues ”centers sur une compétence de communication: par ex., Intercompréhension de deux ou plusieurs langues proches (surtout langues étrangères) (cycle secondaire supérieur); »

- ↑ EuroComRom. March 26, 2017, accessed October 5, 2019 (German).

- ↑ Plurilinguisme - Langues sans frontières - Plurilinguismeet éducation - Goethe-Institut. Retrieved October 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Welcome - Bienvenue. Retrieved on October 5, 2019 (German).

- ↑ Franz-Joseph Meißner: The measurement of the core vocabulary of Romance multilingualism: a didactic analysis of interlingual transparency and frequency research . ( uni-giessen.de [accessed on October 5, 2019]).

- ↑ EuroComDidact ToGo. In: EuroComDidact. Retrieved on October 5, 2019 (German).

- ↑ When more is better. Retrieved October 5, 2019 .