Jacob's Island

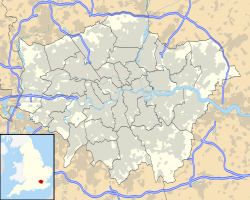

Location of the former Jacob's Island in Greater London |

Jacob's Island was a slum in the London borough of Bermondsey on the south bank of the Thames . It was separated from Shad Thames to the west by St Savior's Dock , where the Neckinger underground river flows into the Thames. To the south and east, the area was bounded by flood ditches, one west of George Row , the other north of London Street (now Wolseley Street ).

Jacob's Island was immortalized in the novel Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens , in which the main villain, Bill Sikes, found a terrible end in the mud of the Folly Ditch . Dickens gives a vivid description of the situation at the time:

“… Quirky wooden galleries, usually built at the back of half a dozen houses, with holes through which you can see on the mud below; Windows, broken and mended, with wooden sticks sticking out from which to dry the linen that is never there; Rooms so small, so dirty, so cramped that the air seems too foul even for the filth and filth in it; wooden chambers that stretch outward over the mud and threaten to fall into it - as has happened several times; Dirt-smeared walls and rotten foundations, every repulsive facial feature of poverty, every disgusting sign of filth, rot and rubbish: all of this adorns the shores of Jacob's Island. "

Dickens learned about this impoverished and disgusting place through the river police officers with whom he occasionally patrolled. Whenever a local politician once again attempted to deny the very existence of Jacob's Island, Dickens made no excuse and described the area as "the dirtiest, strangest and most remarkable of all places hidden in London". The area was known to be dirty at the time and was described in the Morning Chronicle in 1849 as "the capital of cholera " or " Jauchenvenedig ". The flood ditches were filled in in the early 1850s, the slums torn down and warehouses built instead.

Henry Mayhew described Jacob's Island as follows:

“When you stepped into the Pestilence Island area, there really was a smell of corpses in the air and a feeling of nausea and heaviness came over anyone who was not used to soaking up the damp atmosphere. Not only your nose, but your stomach too, told you how full the air was filled with hydrogen sulfide fumes ; and as soon as you crossed one of the quirky, rotten bridges over one of the stinking canals, the black color of the door frames and window sills into which the once white lead had turned, you knew as sure as if you had done a chemical analysis that the Air was heavily impregnated with that deadly gas. The thick bubbles that now and then rose in the water showed where at least some of the diabolical mixture was coming from, while the open, doorless chests that hung over the water and the dark streaks of dirt down the walls, where the drains from every house poured into the flood ditches, indisputably indicating how these flood ditches were polluted.

The water was covered with scum, almost like a spider's web, and shimmered through the grease in all colors. Large amounts of rotting seaweed drifted in it and the swollen carcasses of dead animals got stuck on the bridge piers and threatened to burst due to the rotting gases. Indescribable filth was piled up along the banks, the phosphorus smell of which told about the proportion of rotting fish, while the oyster shells looked like pieces of slate through many layers of dirt and mud. In some parts of the island the water was as red as blood from the remains of leather paint that ran in from the stinking tanneries nearby ”

Jacob's Island was badly bombed during World War II and only a single Victorian warehouse has survived to this day. In the past twenty years the island has undergone extensive urban development.

Web links

- Image and map of Jacob's Island in Bermondsey (1813) (English)

- Image of Jacob's Island in Bermondsey (ca.1880) (English)

- Map of Dickens' London (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Letter to the editor to the Chronicle of September 24, 1849 from: Selection from London Labor and the London Poor . Oxford University Press (1965). S. XXXVI