Kaitai Shinsho

Kaitai Shinsho ( Japanese 解体 新書 , lit. "New Book of Anatomy") is the most famous translation in early modern Japanese medicine. The book, printed in 1774, marked a turning point in the history of science.

background

In the course of the growing interest in anatomy in Japan since the second half of the 17th century, Yamawaki Tōyō carried out the first autopsy of a corpse in 1754 , which was followed by other sections that drew attention to Western anatomy books.

A group of ambitious doctors in Edo interested in Western medicine, including Sugita Genpaku , Maeno Ryōtaku , Nakagawa Jun'an and Ishikawa Genjō, studied the Dutch edition of the anatomical tables by Johann Adam Kulmus . According to Sugita, two medical officers of the government, Okada Yōsen ( 岡田 養 仙 ) and Fujimoto Rissen ( 藤 本 立 泉 ), had repeatedly glanced inside the body at sections and explained that the deviations from the images in Chinese works were probably due to a different body structure of Chinese and Europeans would be based. After all sorts of debates, it was decided to take a look inside a corpse. For this they moved to the Kozukappara execution site in northern Edo in 1771 . An old man from the layer of the soiled, who had done this before, dissected the corpse of a woman named "Green Tea Old" (Aocha-baba) and took out various organs. She was deeply impressed by the correspondence between the pictures in her Dutch book and what was shown to them. At the same time, everything was different from what had been written about it in Chinese works. Then they looked at some of the bones that were lying around on the execution site. Their shape also completely matched the illustrations in their book. On the way back they decided to translate the text together.

However, they lacked the necessary language skills. The only one who had a small glossary and Pierre Marin's Dutch-French dictionary, and had some experience in developing Dutch sentences, was Maeno Ryōtaku. According to Sugita, the group met six or seven times a month. Every word had to be laboriously developed, which sometimes took days. Other interested parties joined them. But some had their own goals and left the circle again. There were also big differences in terms of language skills and commitment. Ultimately, it was Maeno who did most of the translation. Its Japanese version was transposed into the written Chinese language ( Kanbun ) by Sugita .

In 1773 a text was written that had been rewritten eleven times. Sugita admits in his memoirs that the text would not have come about without Maeno, but over the course of time he intervened more and more in the editorial team and, for the sake of clarity, rewrote the translation "now here, now there". At that time, Maeno suddenly withdrew from the project. Sugitas remains rather taciturn on this matter in his memoirs. As far as the sources indicate, Maeno wanted to further edit what he believed to be incorrect text. Sugita, on the other hand, strived for publication as quickly as possible and ignored these concerns.

In order to test the market and also to test the reaction of the authorities, who used to forbid unpleasant publications, Sugita and Nakagawa had a five-page advance notice "Brief illustrations of anatomy" ( Kaitai Yakuzu 解体 約 図 ) printed. The learned court doctor Katsuragawa Hoshū probably contributed greatly to the removal of possible obstacles by having a copy presented to the Shogun through his venerable father . Further copies went to the imperial councils and influential personalities at the court of the Tenno in Kyoto .

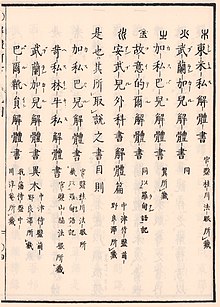

The censorship did not intervene, and in 1774 the renowned publisher Suharaya Ichibē ( 須 原 屋 市 兵衛 ) published the “New Book of Anatomy” ( Kaitai Shinsho ). Sugita Genpaku is named as the translator. Nakagawa Jun'an, Ishikawa Genjō and Katsuragawa Hoshū follow in fine gradation as reviewers and mentors. Maeno's name only appears in a dedication by Yoshio Kōsaku , who was probably the most knowledgeable interpreter of his time in European medicine as well as in the Dutch language.

On the structure of the work and the sources

The Kaitai Shinsho is generally considered to be a translation of Ontleedkundige Tafelen (1731), but a comparison with the original text shows that Maeno had left out Kulmus's notes, which make up most of the book. A number of illustrations come from the writings of Thomas Bartholin , Steven Blankaart , Volcher Coiter , Jan Palfijn , Ambroise Paré and Govard Bidloo . The frontispiece was taken from the anatomy of Juan Valverde de Amusco (Antwerp, 1566). There are also various additions by Sugita, at one point even the lengthy correction of an error in Sugita's advance notice.

As a result of the inadequate language skills of those involved and the multi-stage translation process, a text was also created whose content is based on the documents, but structurally and in small details can hardly be viewed as a translation in the modern sense.

Translation of technical terms

Basic names for heart, stomach, kidney, etc. had already come into the country through Chinese medicine. You had to create new terms for things you didn't know. There were three methods to choose from:

- With compound names like ndl. slagader linked the Chinese translations of the components slag ( dō ) and ader ( myaku ) to dōmyaku .

- In other cases, completely new names were created, such as B. for ndl. zenuw (nerve) based on ideas of traditional medicine, the coinage shinkei (from shinki , and keiraku , meridian).

- Often, however, the understanding of the anatomical facts was insufficient and the Dutch name was translated into Chinese characters. From ndl. klier (gland) became kiriru ( 機 里爾 ), vet (fat) became hetto ( 荷 都 ) etc.

The transliterations of the latter group did not last long. They were soon replaced by content-oriented new issues. Some terms in the first and second groups entered modern Japanese, and some even became common in Chinese and Korean.

Historical meaning

Those involved were aware of the problems of the translation as well as the unsatisfactory quality of the illustrations at the time of publication. Soon afterwards, Ōtsuki Gentaku, a student of Sugita and Maeno, began a revision with others. The manuscript, completed in 1795, was not printed until 1826 under the title "Revised New Book of Anatomy" ( Jūtei Kaitai Shinsho ). It also includes an extensive discussion of the nomenclature problems.

In those years the study of the Dutch language and medicine had made great strides. In 1805 Udagawa Shinsai ( 宇田 川 榛 齋 ) published the influential "Guide to Medicine" ( Ihan Teikō 医 範提 綱 ) with high-quality copperplate engravings and elaborate anatomy based on the writings of Blankaart, Palfijn and Winslow . In this respect, interest in the Kaitai Shinsho soon waned . Philipp Franz von Siebold , who collected relevant Japanese books, apparently did not know this work. Other European travelers to Japan took no notice either. It only aroused renewed interest in the Meiji period , when the country's doctors reviewed the history of the modernization of their discipline. Sugita's memoirs played an important role here.

Nevertheless, regardless of all weaknesses, the Kaitai Shinsho is of great historical importance. In contrast to the retrospectively conceived “Book of Organs” ( Zōshi 蔵 志 ) by Yamawaki Tōyō and much more so than the “Book of the Corpse Section ” ( Kaishi-hen 解 屍 編 ) by Kawaguchi Shinnin ( 河口 信任 ), which emphasized his own observations , Sugita turned Genpaku versus Chinese anatomy. The Kaitai Shinsho demonstrated to the country's physicians, who were largely isolated from the outside world, that it was possible, with appropriate effort, to make use of a Western specialist text without the help of Europeans and interpreters from the Dejima branch ( Nagasaki ). With this book, reading and translation became a fundamental means of modernizing science and technology.

Legends

The circumstances of the origin of the Kaitai Shinsho only became known through the memoirs of Sugita Genpaku. His manuscript, written at the advanced age of 83, was revised by his student Ōtsuki Gentaku in 1815, but was not put to print until 1869 by Fukuzawa Yukichi , one of the leading figures in modernization. On the occasion of the first meeting of the Japanese Society of Medicine ( Nihon igakkai ) in 1890, Fukuzawa published a new edition, which he provided with a moving foreword. With this pressure, Sugita Genpaku and the “New Book of Anatomy” gained a prominent place in early modern Japanese medical history.

As the title "Beginning of the Dutch Studies" ( Rangaku Koto Hajime 蘭 学 事 始 ) indicates, Sugita ignores the more than a hundred years of previous research on Western medicine and other disciplines conveyed through the Dutch trading establishment and contends with the development of Kaitai Shinsho The beginning of a historic turning point. Sugita's description of the painful, tough translation work met with a great response. The picture he painted of a rudderless and rudderless ship in the middle of the ocean with no prospect of help moved not only Fukuzawa deeply. Many Japanese readers of the 19th and early 20th centuries tried to tap into Western science and technology even under similarly difficult conditions. In connection with the age memoirs Sugitas and their dissemination by Fukuzawa, the Kaitai Shinsho acquired a symbolic power that far exceeds its actual medical-historical significance.

The title is so well known today that it is used in combination with other subject areas to advertise the book in question as "dissecting" and groundbreaking: Mokkōzō no Kaitai Shinsho ("Kaitai Shinsho of wooden structures"), Fukuon no Kaitai Shinsho ("Kaitai Shinsho of the Gospel ") etc.

See also

swell

- Sugita Genpaku et al .: Kaitaishinsho. Suharaya Ichibē, Edo 1774. ( 與 般 亜 覃 闕 児 武 思 著, 杉 田 玄 白 訳, 吉雄永 章 撰, 中 川 淳 庵 校, 石川玄 常 参, 桂川甫 周 閲, 小 田野 直 武 [図] 『解体 武』 』 : 須 原 屋 市 兵衞, 安永 3 [1774] 年刊 )

- Rangaku kotohajime. The beginnings of the "Holland customer" . Translated by Kōichi Mori. In: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 5, No. 1 (1942), pp. 144-166 (Part I); Ditto, Vol. 5, No. 2 (1942), pp. 501-522 (Part II)

- Maeno Ryōtaku shiryōshū . Ōitaken Kyōikuiinkai (Ōitaken Sentetsu Sōsho), Vol. 1, 2008; Vol. 2, 2009; Vol. 3, 2010 ( 『前 野 良 沢 資料 集』 、 駿 台 史学 会 大分 県 教育 委員会 (大分 県 先哲 叢書) )

literature

- Katagiri, Kazuo: Sugita Genpaku . Tōkyō, Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1971.

- Katagiri, Kazuo: Chi no kaitakusha Sugita Genpaku . Tōkyō, Bensei Shuppan Kōbunkan, 2015.

- Michel, Wolfgang: Exploring the "Inner Landscapes" - The Kaitai shinsho (1774) and its Prehistory . In: Yonsei Journal of Medical History, Vol. 21 (2), 2018, pp. 7-34 .

- Nagayo, Takeo: History of Japanese Medicine in the Edo Era . University of Nagoya Press, 1991.

- Numata, Jirō: The Acceptance of Western Culture in Japan: General Observations . In: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 19, No. 3/4 (1964), pp. 235-242.

- Ōtori, Ranzaburō: The Acceptance of Western Medicine in Japan . In: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 19, No. 3/4 (1964), pp. 254-274.

- Torii, Yumiko: Maeno Ryōtaku - bangaku no isai . In: Michel / Torii / Kawashima (ed.): Kyūshū no rangaku - ekkyō to kōryū. (Kyoto, Shibunkaku Shuppan, 2009, pp 59-65 ,鳥井裕美子,川嶌眞人共編「九州の蘭学越境と交流」思文閣鳥井裕美子「前野良沢学の異才」 (ヴォルフガングミヒェル出版) ).

- Torii, Yumiko: Maeno Ryōtaku . Ōita-ken Kyōikuiinkai (Ōita-ken Sentetsu Sōsho), 2013 ( 鳥 居 由美子 『前 野 良 沢』 大分 県 教育 委員会 (大分 県 先哲 叢書) ).

Web links

- Kaitai Yakuzu , the advance notice of the Kaitai Shinsho (digitized, Keio University)

- Kaitai Shinsho (digitized, National Diet Library)

- Jūtei Kaitai Shinsho (digitized, National Diet Library)

- Illustrations from the Kaitai Shinsho (digitized National Library of Medicine)

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the background and the details of the development see Michel (2018).

- ↑ lit. Burial mound field; also called Kozukahara and Kotsukappara.

- ↑ These were considered unclean because they involved killing animals, processing meat, tanning skins, and so on. More under Buraku .

- ↑ Rangaku kotohajime , (German transl .) I, p. 162ff.

- ^ Pieter Marin: Groot Nederduitsch en Fransch Woordenboek , 1730

- ↑ Rangaku kotohajime , (German transl .) I, 165ff.

- ↑ Rangaku kotohajime , (German transl .) II, p. 221

- ↑ Only a few years earlier, Gotō Rishun's "Conversations about the Dutch" ( Oranda-banashi , 1765) was banned .

- ↑ Rangaku kotohajime , (German translation) II, 222f.

- ↑ Kaitai Shinsho , Forewords, fol. 2

- ↑ Kaitai Shinsho , instructions for use ( hanrei ), fol. 2f.

- ↑ Kaitai Shinsho , Part 4, Chapter Spleen

- ↑ Rangaku kotohajime , (German transl .) I, p. 164