Value chain

The value chain or value chain ( English Value Chain ), the stages of production as an ordered sequence of activities. These activities create values consume resources and are in processes linked. The concept was first published in 1985 by Michael E. Porter in his book Competitive Advantage :

“ Every company is a collection of activities through which its product is designed, manufactured, sold, shipped and supported. All of these activities can be represented in a value chain. "

' Value chain' is often only used to refer to the representation (e.g. as a value chain diagram ). In the extended and proper sense, however, the actual or potential processes that take place form the value chain. B. is also called the service chain. According to D. Harting, “value chain” describes “the stages of the transformation process that a product or service goes through, from the starting material to its final use”.

Basic model

The value chain is made up of the individual value activities and the margin . Value activities are activities that are performed to produce a product or service. The margin is the difference between the yield that this product generates and the resources used.

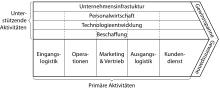

The graphic shows the basic model of the Porter value chain. Primary activities are those activities that make a direct, value-adding contribution to the creation of a product or service. In the basic model are inbound logistics , production , outbound logistics , marketing and sales and customer service . Support activities are activities that are necessary to carry out the primary activities. They thus make an indirect contribution to the creation of a product or service. In the basic model, these are company infrastructure , human resources , technology development and procurement .

A company's value chain is linked to the value chains of its suppliers and customers. Together they form the value chain system of an industry.

Definitions

In order to define the value chain, all company activities must be assigned to the corresponding activity types. Within the activity types, the activities are to be distinguished from one another according to the following criteria:

- Activities from different economic areas

- Activities with a high potential for differentiation.

- Activities with a significant or increasing cost component.

Non-competitive factors, however, can be summarized. The classification of the activities requires creativity and judgment. The specific situation of the company and the industry must be taken into account. A trading company will pay particular attention to inbound and outbound logistics, and a goods producer to operations.

Each category of primary and support activities can be broken down according to the following criteria:

- direct activities

- They are directly involved in creating value for the customer (e.g. assembly, machining, field service, advertising, product design, research).

- indirect activities

- They ensure the continuous execution of direct activities (e.g. maintenance, scheduling, plant operation, sales and research administration).

- quality control

- It ensures the quality of the direct and indirect activities (e.g. monitoring, quality control, tests).

Traditional cost accounting usually summarizes the indirect and quality assurance activities as overhead costs. However, this means that information relevant to competition is lost. The division of the activity types into direct, indirect and quality assurance activities, on the other hand, provides valuable information for diagnosing competitive advantages. The indirect and quality assurance activities make up a large and rapidly growing cost component in many industries . Thanks to their interrelationship with the direct activities, they also play a decisive role in differentiation and / or cost management (e.g. higher maintenance costs reduce the costs of machines).

A further development of the value chain, the value circle represents.

Porter's concept follows a station model in which the model elements are primarily the locations of production. Analogous to this, models were later developed that follow a flow model in which the material or value flows are the primary model elements. Both model approaches can complement each other, but not completely replace them.

Pulled value chain: Higher effectiveness (doing the right things) and efficiency (doing things right) of processes seem more achievable if the value chain ideally follows a "suction strategy" in which every requirement comes from the (final or intermediate) recipient. This principle applied in lean management is called “drawn value chain” (as opposed to “pushed”); in this is called the "pull principle".

How to proceed with the analysis

An in-depth analysis usually requires the creation of several value chains (e.g. for each product group or strategic business unit). In this way, differences between geographical areas, between product or customer segments as well as the interdependence between the business units can be made visible.

The definition of the value chain can prove to be very complex. Esser therefore proposes a simplified procedure that can be deepened for individual value activities as required. The structure and process organization of the company serves as a framework for the assignment of the activities in the value chain. This ties in with the experience of the executives and the operational information and accounting systems. The definition of the value chain must follow the principle of "completeness before detail". With regard to an efficient way of working, it is advisable to provisionally subdivide your own value chain and that of your most important competitors before the actual strategy meeting.

analysis

Once the value chain has been defined, you can then answer the following questions :

- What are the costs of the individual activities?

- Are the activities customary in the industry? Do they lead to a competitive advantage or to a cost disadvantage (because customers do not even notice this activity)?

- Is the value chain tailored to the customer's purchase criteria?

- How are the value activities linked within your own value chain?

- How are the value activities linked to those of the suppliers and customers?

- What is the sub-step used for (error prevention, damage minimization ...)?

- Are there any redundant or outdated regulations?

Strategic cost analysis

Existing and potential competitive advantages of a company can be determined from the cost structure and the differentiation potential of all value activities. The choice of the desired competitive advantage (cost advantage or differentiation) determines the focus of the value chain analysis. If you focus on a cost advantage, the value activities that determine cost behavior are in the foreground. If the goal is differentiation, then you use the value chain to find out how you can stand out from the competition. However, costs are also of crucial importance in differentiation strategies. A better service than the competition is only worthwhile if the price premium that can be achieved is higher than the cost of differentiation.

The cost analysis based on the value chain enables a strategic and holistic analysis of the cost behavior of a company. It can point out ways to a permanent cost advantage. However, it does not replace (detailed) cost accounting and key figure analysis. A strategic cost analysis is especially necessary for companies that have little or no differentiation options in their industry and can therefore only achieve competitive advantages on a cost and price basis (this is the case, for example, with many simple consumer goods).

The first step is to assign the costs (operating and plant costs) to the individual value activities. Activities that take up a significant or rapidly increasing proportion of the costs deserve special attention. However, no computational precision is required in this cost analysis. It is sufficient to divide purchased inputs, personnel costs and investment costs into categories. This breakdown alone can provide valuable information on ways to reduce costs (for example, if you discover that the inputs purchased account for a significantly larger share of the costs than you assumed).

In the second step, one records the costs of the value activities of the most important competitors. Although this is difficult, it is very important to assess your own situation. One is mostly dependent on estimates. Just knowing whether a competitor is performing a value activity more cheaply or costly is very useful.

In a third step, you analyze the differences between your own value chain and that of your competitor. The question of the reasons for a different cost structure is of particular interest. In order to answer them, one has to identify the structural and procedural cost drivers. In this way one can show the possibilities for improving the relative cost position. A company can improve its relative cost position by changing its position vis-à-vis cost drivers and / or changing the composition of the value chain in its favor. The following cost drivers explain where and why different competitors' costs differ:

- of scale economies of scale such. B. through more rational implementation or a disproportionate increase in overhead costs or progressions , e.g. B. due to greater complexity or increased coordination effort

- Learning processes lead to higher work productivity, product design suitable for production, etc.

- Structure of the capacity utilization , the proportion of fixed costs in the total costs

- Links within the value chain with suppliers and buyers

- Interrelations , synergies with other strategic business units, e.g. B. Joint production

- Vertical integration , make-or-buy decisions for upstream and downstream activities

- Time selection , e.g. B. Pioneering advantages and disadvantages, cyclical interest costs

- strategic decisions , e.g. B. Product design and offerings, expenses for marketing and technology development, choice of sales channels

- Location influences costs for labor, raw materials, energy, taxes, etc.

- external factors , e.g. B. Government measures / regulations

- organizational skills , e.g. B. Time management, process orientation, etc.

These cost drivers can be mutually reinforcing (e.g. a good location often depends on the choice of time) or neutralize (e.g. economies of scale are neutralized by poorer utilization). It is usually extremely difficult or even impossible to precisely quantify the cost effectiveness of the driving forces. In many cases, however, it is sufficient to grasp the relationships intuitively. However, the cost analysis often proves to be very difficult in practice, since the conventional cost accounting systems only record cost categories (wages, travel expenses, depreciation, etc.). Therefore, cost management has shifted more and more to indirect costs (overheads). With the approach of activity-based costing ( Activity-based costing ) will try to reverse this trend and to allocate the costs back individual activities. Activity-based costing aims to make overhead costs transparent and to avoid all non-strategic overhead costs. A comprehensive understanding of the activity costs requires an expansion of the consideration to the entire value chain of the industry (suppliers, internal activities, strategic partnerships). This then allows you to compare your own internal costs with those of your most important competitors. The starting point of activity-based costing is activity analysis , which should provide answers to the following questions:

- Who is the customer of the activity or the process?

- Input / output of the activity / process?

- Total cost of the activity / process per year?

- primary cost driver?

- financial performance metrics?

- Productivity metrics?

The analysis, which is best done in a discussion with those directly involved, reveals a large number of cost drivers and thus the relationship to the relevant business decisions. It also enables the description of the internal processes and illustrates the diversity of the activities.

The activity-based-costing approach is limited to the analysis of overhead costs. It is therefore not an independent cost accounting system, but rather has to be integrated into the traditional cost type and cost center accounting. Activity-based costing is used both for product costing and for evaluating processes and their services. However, this approach is particularly useful for analyzing the entire value chain from a strategic point of view. Starting from the same activity database, the data can be specifically allocated to “ strategic activities ”. In this way we arrive at an important basis for making decisions about revising or adapting the strategy.

Application in practice

The value chain as a methodological ideal and as a demanding instrument allows company activities to be analyzed comprehensively and consistently. It combines company analysis with strategy development, in that the relative strengths and weaknesses in the value chain form the basis for the determination of core competencies and then enable the formulation of competitive strategies . The practical handling of the value chain is fraught with some problems:

- The analysis requires considerable expenditure of time and method.

- In practice, “ strategic planning ” usually takes place in the form of moderated work sessions with the responsible managers. A comprehensive value chain analysis in this context is often too time-consuming, or it encounters a lack of acceptance and motivation. This difficulty can be countered with appropriate preparation for such meetings.

- When quantifying the value chain, the usual account structure (e.g. overhead costs , fixed costs , direct wage costs) rarely coincides with the value activities. Department-oriented cost accounting must therefore be transformed into activity- or process-oriented cost accounting in a complex process. The assignment of costs to value activities (especially when these are closely linked and extend over several strategic business units) is very difficult and remains largely a matter of judgment.

If the effort for a quantitative value chain analysis is not worthwhile, it is advisable to use the traditional cost structure analysis and the existing cost accounting system. Used flexibly and appropriately for the situation, the value chain is an extremely valuable diagnostic and analysis tool that also provides good systematic support for the other analysis tools.

See also

literature

- Michael E. Porter : Competitive Advantage Achieve and maintain top performance . Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-593-36178-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Eugene Porter: Competitive Advantage. Achieve and maintain top performance. Translated from English by Angelika Jaeger. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-593-33542-5 .

- ↑ D. Harting: Value creation in new ways. In: procurement current. 7/1994.

- ↑ Klaus F. Adeling: Sail tainment. Self-published, 1999, ISBN 3-89811-086-9 . on-line

- ↑ J&M: Lean SCM ( Memento from March 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ W.-M. Esser: The value chain as an instrument of strategic analysis. Stuttgart 1994.

- ↑ ME Porter: Only strategy ensures high yields in the long term. In: Havard Manager. No. 3, 1997, pp. 42-58.

- ↑ Ness / Cucuzza 1995, pp. 130-138; Miller / Vollmann 1985, pp. 142-150; Johnson / Kaplan 1987.

- ↑ Haselgruber / Sure 1999, p. 41.

- ↑ for example Cooper / Kaplan (1988); Esser (1994); Hergert / Morris (1989)

- ↑ for example Pipp (1990), pp. 26 and 32.