Operation Silver

The Operation Silver (with the British as Operation Lord , or surgery Conflict called) was occupied postwar Austria a joint espionage action of the British Secret Intelligence Service and the American CIA . In Vienna , the telephone lines of the Red Army headquarters were tapped using a tunnel dug under the Soviet-occupied sector of the city. The tunnel was in operation from 1949 to 1952 and provided vital information during the Korean War . Due to its success, the action was later repeated in Berlin as Operation Gold .

prehistory

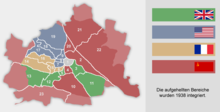

In the immediate post-war period, US intelligence activities in Austria were mainly carried out by the Counter Intelligence Corps , the military intelligence service of the US Army . From 1946 onwards, however, numerous military personnel in Europe were released back into the United States into civilian life, which drastically reduced the workforce. In the short term, this led to a dangerous advantage for the Soviet secret services, MGB , MWD and GRU . This gap should now be filled by the civilian secret service. For this purpose, the Central Intelligence Agency was founded in autumn 1947 as the successor organization to the OSS and its staff in Austria was massively increased. The CIA Austria was stationed primarily in the American sector in Vienna, where its agents were disguised as diplomatic personnel. The locations were the collegiate barracks in the 7th district and the Allianz insurance building on Währinger Strasse in the 9th district . The second base in Austria was Salzburg , the headquarters of the United States Forces in Austria . However, after the surprise communist coup in Prague in February 1948, the US authorities realized that their investigation was still inadequate.

Listening tunnel

In the course of the VENONA project , the British secret service succeeded for the first time in deciphering encrypted Soviet messages. SIS boss Stewart Menzies (code name: "C") then sent his agent Peter Lunn to Vienna with the order to find weak points in the Soviet communication network in order to be able to intercept decryptable messages. In 1948, the British Enlightenment noticed that the Soviet authorities were also using the old telephone network of the former Reichspost to send information to Moscow . From the headquarters of the Soviet High Commissioner in the Hotel Imperial , which is located on the border of the 1st district on Stalinplatz and where the secret service MWD (previously NKVD ) was also housed, the Soviets controlled a land corridor to the eastern Vienna city limits. The subsequent Lower Austria was also occupied by the Soviets. It was believed that the copper cable network buried in the ground could be used for communication to the east without danger. By chance, however, the British foreign intelligence service SIS / Mi6 noticed that the Soviets were using a telephone switch in Schwechat, which was not far from the British sector in Simmering (11th district). By digging a tunnel only 21 meters (70 feet ) long, it would be possible to get under the switchboard and tap into the telephone lines there.

The British made a detailed plan. They bought a shop on a main street. Clothing made of English tweed fabrics was sold there for camouflage . This product was so popular among the Austrian population that the business even made a profit. A private house was also bought nearby to serve as the starting point for the tunnel. The operation was given the code name Operation Lord . In 1949 the tunnel was finished and the monitoring system could go into operation. The information obtained was evaluated together with the CIA-Austria, which in turn gave the company the code name Operation Silver . In this way it was possible, among other things, to get the Red Army's deployment plans.

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the United States had great concerns about the extent to which it could get involved there without irritating the Soviet Union too much. However, information from the Vienna listening tunnel made it possible to establish that the Soviet Union was not interested in expanding the conflict to Europe at the time. The American engagement in Korea could be expanded accordingly.

After three years of successful wiretapping, the action had to be ended. A tram caused such tremors that the tunnel collapsed in 1952. The source of information was thus dried up. The Soviets, however, hadn't noticed anything of the action.

Operation Gold

The following year, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Allen Welsh Dulles as the new director of the CIA. He was enthusiastic about the results that the Vienna listening tunnel had delivered and urged that the same trick should be tried again, this time in Berlin. Operation Gold was started again together with the British intelligence service , which was now meticulously planned to build a similar tunnel into the Soviet sector of Berlin. This plan was to be the most complex secret service project in Berlin in the 1950s. The British agent Peter Lunn, who was successful in Vienna, was transferred to Berlin for this purpose and appointed head of the SIS section there. In August 1954 the excavation work began and on February 25, 1955 the listening station was put into operation. Communication between the Red Army and the Soviet secret services in Berlin could be tapped for eleven months before the tunnel was discovered. What Dulles had not known, however, was that the Soviets had been warned about this second tunnel by a double agent in British intelligence. It was not until 1961, after Blake had been arrested and convicted as an agent, that Western intelligence services realized that the tunnel had ceased to be kept secret long before it was built. Although Dulles has publicly stressed the success of Operation Gold, CIA analysts are divided on the value of the information gathered. One of the evaluations concludes that the Soviets only ran petty communications over the tapped cables to maintain the illusion that they had no aggressive intentions against West Berlin. The operation cost gold are with 6.7 million US dollars given.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Operation Gold. In: Der Spiegel. Issue 39/1997.

- ↑ RCS Trahair: Encyclopedia of Cold War espionage, spies, and secret operations. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 0-313-31955-3 , p. 243.

- ^ Erwin A. Schmidl: Austria in the early Cold War 1945-1958: Spies, partisans, war plans. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-205-99216-4 , p. 96.