Pacta conventa (Croatia)

As Pacta conventa (Negotiated contracts) or qualiter (after the first word) is referred to about 250 words long text of a letter dated 1102 alleged contract between King Koloman of Hungary and the "twelve tribes" of Croats reported. Koloman is said to have renounced a battle on the Drava and granted the named Croatian greats the right to their possessions, tax exemption and limited military service. According to this, the Pacta conventa should have regulated the relations of the Croatian nobility to the Hungarian king before he was also crowned King of Croatia in Biograd na Moru . The historical situation therefore suggests that a meeting of the nobility and the existence of an agreement are likely.

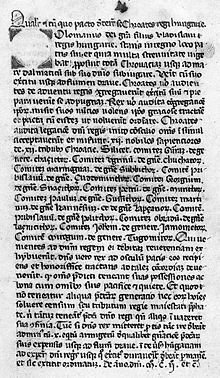

The text was handed down in a manuscript of the chronicle of the archdeacon Thomas von Split († 1268). Most connoisseurs today regard it as an addition from the 14th century to historically underpin the primacy of the twelve sexes (which only appeared as such in the 14th century and cannot be clearly identified historically).

The authenticity of the pacta conventa was defended by the Croatian side during the nationality struggles of the 19th century, which classified it as an important document in Croatian legal history . It was just as uncritically rejected by the Hungarian side.

Croatia and Hungary before the conclusion of the personal union

Through the marriage of the Hungarian king's daughter Helena , the Croatian king Zvonimir entered into close family ties with the Arpad dynasty. There were also political connections between the two countries. King Géza supported his brother-in-law Zvonimir in the war against Count Ulrich from Carinthia in the 1060s.

When Zvonimir died in 1089, his widow tried unsuccessfully to secure the Croatian throne for her brother Ladislaus , who now ruled Hungary. Instead, Stephen II , the last descendant of the Trpimirović dynasty, was elected king. In his government, which lasted only two years, this could not prevail nationwide. After Stephen's death in 1091, Helena's party got the upper hand again and her brother Ladislaus used the power vacuum in Croatia for a military incursion. He marched without major resistance to Biograd na moru, the royal residence on the Dalmatian coast. But because of a Kuman incursion in Hungary, he had to return home quickly. On the way back he founded the diocese of Zagreb, which was subordinated to the Hungarian church province of Kalocsa. At least in inland Slavonia, Hungarian power seems to have been stable in 1091. In addition, Ladislaus appointed his nephew Álmos as the Croatian king. But this one was probably never crowned, because the crown was owned by the Bishop of Split outside the Hungarian sphere of influence. Without a coronation, Álmos lost increasing recognition in Croatia and in 1093 Petar Svačić was elected king. Petar died in 1097 in the Battle of Gvozd , when he wanted to prevent a troop of the Hungarian King Koloman from passing through to Biograd.

Now there was no candidate for the Croatian throne other than Koloman. Nevertheless, the Croatian nobility hesitated to choose the Hungarian king, who was weakened at the time both internally and externally, as their ruler. Among other things, his brother Álmos challenged him for power in both countries. It was only five years later that Koloman was able to be crowned King of Croatia in Biograd. It is very likely that Koloman made far-reaching concessions to the Croatian nobility for this, as they were written down many years later as the Pacta conventa.

content

The content of the Pacta Conventa was found as an appendix in a copy of the Historia Salonitana dated to the 14th century . Its provisions are reproduced as follows:

The Croatians choose Koloman as their king, his descendants have the right of succession. Croatia was not subjugated, but accepted the Arpad dynasty of its own free will. Therefore the possessions of its inhabitants (meaning the nobility) remain untouched. The king has to recognize the Croatian parliament ( Sabor ), he and his successors have to be crowned in Croatia. The nobility was only obliged to serve in the army within the Croatian borders; beyond the borders, the king has to reimburse the nobility for the costs. The king is entitled to the customary taxes and he is allowed to appoint a deputy ( ban ), who could be compensated for his services with land in Croatia.

The representatives of the Croatian noble families Kačić, Kukar, Šubić , Svačić, Plečić, Mogorović, Gušić, Čudomirić, Karinjanin and Lapčan, Lačničić, Jamometić and Tugomirić are named as contractual partners of the king.

History of the impact of the Pacta Conventa

The Croatian nobility was able to maintain extensive independence for centuries. Specifically, however, that depended on the strength of the respective king. Since most of the Hungarian rulers also had to meet the nobility in their home country, this also applied to Croatia. However, the strong position of the Croatian nobility was based more on personal privilege. Some kings waived the separate coronation in Croatia without this having any political consequences. Through marriages and land acquisitions on both sides of the border, the magnate families of Croatia and Hungary mixed more and more. Many nobles belonged to both noble nations.

However, the legal tradition of the Pacta Conventa was important when the Sabor elected the Habsburg Ferdinand as king in a separate electoral act in 1527 . Ferdinand also recognized the old rights of the Croatian nobility. With the separate adoption of the Pragmatic Sanction , which secured the succession of Maria Theresa in the 18th century , the Sabor also invoked its independence from Hungary. This was the last legal act in which the Pacta Conventa played a role.

controversy

The Pacta Conventa were the subject of heated debates between Hungarian and Croatian historians as early as the 19th century. As part of the so-called historical constitutional law, they were the legitimation basis for political claims of both nations. On the basis of historical law, the Croatian side demanded recognition as a nation with its own statehood within the Danube Monarchy, the Magyars saw Croatia as an integral part of Hungary. In these disputes, the authenticity of the Pacta Conventa was also up for debate.

In research after 1945, the Croatian historian Nada Klaić considered the mention of the twelve tribes as a unit in the Trogir privilege as the main reason for their inauthenticity, while the Croatian historian Oleg Mandić took the opposite position.

See also

Web links

- Hrvoje Jurčić: The so-called "Pacta conventa" from a Croatian perspective , Hungary Yearbook 1969, Munich. PDF (1139 kB, German)

- Nada Klaić: O. Mandić, “Pacta conventa” i “dvanaest” hrvatskih bratstava, Historijski zbornik, XI – XII, 1958–59 , Historijski zbornik 13 (1960), pp. 303–318. PDF (2162 kB, Croatian.)

- Oleg Mandić: O jednoj “recenziji” , Historijski zbornik 13 (1960), pp. 318-320. PDF (387 kB, Croatian.)

literature

1. Sources

- Thomas Archidaconus / Toma Arhiđakon: Historia Salonitana: Povijest salonitanskih i splitskih prvosvećenika . Predgovor, latinski tekst, kritički aparat i prijevod na hrvatski jezik. Ed .: Olga Perić (= Biblioteka Knjiga mediterana . Volume 30 ). Split 2003, ISBN 953-163-189-1 .

2. Representations

- Jánoz M. Bak: Pacta conventa . In: Holm Sundhaussen, Konrad Clewing (Hrsg.): Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe . 2. advanced u. updated edition. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna, Cologne, Weimar 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-78667-2 , pp. 689 .

- Neven Budak: Prva hrvatska stoljeća . Zagreb 1994.

Individual evidence

- Jump up ↑ Bernath M., Krallert G .: Historische Bücherkunde Südosteuropa , Munich / Vienna, R. Oldenbourg, 1980, p. 1324