Price differentiation

Price differentiation (also price discrimination ) is a pricing policy of providers to charge different prices for the same service . The differentiation can be temporal, spatial, personal or objective. With this pricing instrument, providers try to fully exploit the willingness to pay of the customer.

Relationship between the terms price differentiation and price discrimination

The two terms are mainly treated as synonyms . So operationalized e.g. B. Kristin Hansen in her dissertation Special Offers in Grocery Retailing a graphic with the title Price Differentiation by breaking it down according to different forms of price discrimination .

Deviating from this usage, the Federal Agency for Civic Education , following the Bibliographisches Institut Mannheim , rates price discrimination as a “prohibited behavior”. The European Union finally has tourists out that of foreigners from EU countries higher prices may be required as by residents. Such price discrimination (i.e. here: unjustified unequal treatment in the form of different prices) is forbidden by European law. This use of language is based on how the term discrimination is used in sociology and law .

In contrast to this, in economics the use of the term price discrimination is common without containing a value judgment (e.g. about the admissibility or inadmissibility of pricing policy). This usage is based on the meaning of the Latin verb discriminare - "separate, separate, distinguish".

overview

A price differentiation exists when a company charges different prices for the same or similar products that cannot be justified, or not entirely, by differences in quality . For this reason, the strategies of price and product differentiation are closely related. One speaks of real price differentiation as long as the price differences of the different quality levels are greater than the corresponding cost differences.

The goals of price differentiation are the formation of sub-markets with specific demand behavior, the reduction of market transparency in markets with a high degree of standardization, and the possibility of better utilization of free capacities. This can lead to markets being served that would otherwise remain without offers.

Types of price differentiation

Depending on the nature of the market, the provider can pursue different strategies of price differentiation, which, according to Pigou , can be divided into three types. Within economics and in the context of the abuse of market power, one speaks of 1st to 3rd degree price discrimination. In the context of business administration as a concept of price policy, the neutral term price differentiation of the 1st to 3rd order is used.

1st order price differentiation: perfect price differentiation

One speaks of perfect price differentiation if the provider succeeds in receiving the reservation price from every customer . The common practice of rural doctors in the 18th century to adjust the amount of the fee according to the solvency of their patients is one of the examples of perfect price differentiation. But the gift economy can also be an example of perfect price differentiation.

However, the strategy can only be implemented under conditions that are difficult to fulfill, which are given if:

- the individual willingness to pay of the customer is known,

- personalized prices are enforceable and

- resale ( arbitrage ) can be effectively prevented.

The graphic opposite is intended to illustrate this situation in comparison to the monopoly case. The prices p 1 to p 6 reflect the maximum willingness to pay of the corresponding market participants and thus form the demand function of the consumers. The marginal cost function, on the other hand, represents the supply function, so that in the ideal case the price p 6 occurs. If the monopoly provider can set a price, then he would find his optimal profit between the maximum achievable price p 1 and his reservation price p 6 and achieve a profit equal to the amount of the dark blue area. If the conditions for perfect price differentiation are given, his profit can be expanded to include the light blue area.

The total welfare as the sum of the consumer and producer surplus would in this case rise to the level of competition. This is one of the few cases in which a monopoly solution does not lead to an allocation problem in which there is an undersupply of the monopoly good. However, there is a sharp distribution problem because the monopolist receives the entire consumer surplus (KR = 0).

2nd order price differentiation: self-selection

In this case, the assumption about the knowledge of the individual willingness to pay is dropped so that the provider cannot differentiate between individual consumers or consumer groups with regard to their preferences. Nevertheless, the provider is able to determine and exhaust the willingness of consumers to pay with the help of price, quantity and / or product design, because their choices reveal their own preferences.

As part of this strategy, the provider has several options:

- Quantitative price differentiation by linking the price to the quantity sold, for example to identify bulk buyers.

- Qualitative price differentiation with the aim of filtering out quality-sensitive consumers.

- Temporal price differentiation or horizontal price differentiation, for example to take advantage of innovators' high willingness to pay .

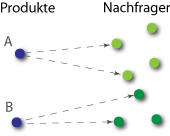

In contrast to perfect price differentiation, the problem of arbitrage is significantly mitigated because the decision about the choice of one of the alternatives is left to the consumer or depends on his preferences and neither the individual consumer groups nor the products are in competition with one another . The graphic shows a split in the demand for two variants of a product that differ with regard to a characteristic such as quality, so that two separate sub-markets arise with their own consumer behavior. It could also be a product with two different prices depending on the quantity, which also triggers an optimization process for the buyer.

Example: Marketing of film rights

When it comes to the exploitation of film rights, the film industry and film rights dealers rely, among other things, on horizontal price differentiation, in which the films successively pass through all levels of demand. Shortly after the cinema release in the country of manufacture (e.g. USA ) or increasingly at the same time, the localized versions are released in foreign cinemas. One or more video versions will appear later, followed by pay-TV broadcasts . After about 24 months, the films finally reach the large free TV channels, only to end up with small niche channels later.

See also: Film exploitation chain

Example: subscription prices

Depending on the payment method , the prices for long-term contracts vary. Publishers and transport associations offer different tariffs depending on whether payment is made annually or quarterly.

3rd order price differentiation: segmentation

A segmentation of consumers into groups with different levels of willingness to pay based on income differences provides a further possibility for price differentiation. Here, a characteristic of a distinguishable group of customers is used to set the price and an associated price is determined. When pricing z. B. assumed the following relationships:

- Belonging to a social group that indicates income and a willingness to pay accordingly: According to the assumption underlying the calculation, students and pensioners react much more sensitively to a price change than other social groups.

- Spatial price differentiation or vertical price differentiation, with which it is possible to work on several markets with different levels of prosperity in parallel.

Example: theater tickets

The sale of discounted theater tickets to schoolchildren is not necessarily based primarily on the desire to give young people access to cultural goods , but on a strategy of price differentiation, because

- Students have low solvency compared to employed people and

- Losses decrease or profits increase when the number of unoccupied places decreases, regardless of the amount of the price asked. This group of visitors thus also contributes to (approximation to the ideal of) cost recovery of the event.

- In addition, such measures can also be used to bind the next generation of full-price visitors to the theater by developing a corresponding preference at an early stage.

A similar situation can be found with the pricing of semester tickets.

Example: Entrance to leisure facilities

Many discounts for families or senior citizens give the impression that private providers think in terms of the welfare state . In fact, reduced admission prices or even free admission for children increase the willingness of their adult companions to accept the offer. "Envy reactions" of other visitors do not usually arise because they have no disadvantage from the discounts for children: Couples without children do not pay more than couples with children.

Senior discounts increase the willingness of grandparents to accompany their grandchildren (and to relieve their parents, which in turn increases their willingness to visit the facility). However, if z. E.g. with a lower age limit of 60 years for the use of the senior discount, 59-year-olds who are no longer gainfully employed for health reasons and who visit the facility because of their grandchildren have to pay the full entrance fee, while high-earning 60-year-olds who are not accompanied by children have to pay the full entrance fee If you receive a senior discount, there may be discussions about the appropriateness of the tariff structure.

Such discussions are of practical importance for the pricing policy of a provider especially when the price differences are relatively large. Then there is the risk that the provider's pricing will be “denounced” in public (with the risk of boycott measures against the provider). The state may sanction “discrimination” in the form of a concrete prohibition of discrimination (here: because of prohibited age discrimination ).

Legal admissibility of price differentiations

In general, price differentiations, especially those of the 1st and 2nd order, are permissible in market economies and are considered legitimate. Restrictions apply to cases in which a provider has market power that comes close to a monopoly, and to third-order price differentiations that are assessed by the legislature, authorities and courts as deliberately unjustified disadvantage of certain population groups.

Abusive exploitation of a dominant position

For companies that dominate the market, but also for markets with a few providers, there are legal provisions that restrict the freedom of providers to set prices. They are intended to protect competition.

Company as a contractual partner

According to Article 102 of the TFEU Treaty (TFEU) and Section 19 of the GWB Paragraph 4, the abuse of a dominant market position is prohibited (but not just holding or exercising such a position). According to Art. 102 TFEU sentence 2c, this abuse of power can consist in particular in the application of different conditions for equivalent services to trading partners, which puts them at a competitive disadvantage. The legal literature distinguishes between:

- Abuse of exploitation : setting prices or conditions that are above the level of competition and

- Abuse of disabilities : measures aimed specifically against the competition, in particular undercutting, exclusivity agreements or refusals to deliver

The determination of a dominant position via the market share and the determination of the competitive prices are difficult. In competition law practice, strategies are viewed as abusive if they have a negative impact on the structure of a market in which a dominant company is already operating, especially if they restrict the maintenance or development of competition.

End users as contractual partners

The provisions of Article 102 TFEU sentence 2a (unreasonable prices as an abuse of power) can also be applied to price discrimination against end consumers.

Transfer of the prohibition of arbitrariness to non-state economic subjects

In the case of bulk deals, incomprehensible price differences that are based on the (non-) affiliation of the buyer to a social group can be considered a violation of the General Equal Treatment Act in Germany and the Federal Act on Equal Treatment in Austria . In particular, price differentiations based on the characteristics of “race” and ethnic origin, gender, religion and belief, disability, age (of any age) and sexual identity can be prohibited. By applying the ban on discrimination to private business subjects, the third-party effect of fundamental rights (here: equal rights) is expanded.

literature

- Hermann Diller: Price Policy . 4th edition. Kohlhammer 2008. ISBN 978-3-17-019492-2

Web links

- Treaty establishing the European Community, Chapter 1: Competition rules

- Law against Restraints of Competition, Section 19: Abuse of a dominant market position

- Price differentiation graphic (PDF file; 12 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kristin Hansen. Special offers in grocery stores. An empirical analysis for Germany . Cuvillier Göttingen. 2006, p. 24 ( online )

- ^ Bibliographical Institute / Federal Center for Political Education: Price Discrimination . 2013

- ↑ European Union: Price Discrimination

- ↑ Klaus Schöler: Fundamentals of Microeconomics. An Introduction to Households, Firms and the Market Theory , 3rd Edition. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2011, [1] pp. ~ 204-205

- ↑ Hal R. Varian : Grundzüge der Mikroökonomik , 8th edition, de Gruyter Oldenbourg 2014, p. ~ 513

- ↑ Friedrich Breyer: Microeconomics. An introduction , 6th edition, Springer 2008, p. ~ 95

- ^ Pons Latin-Deusch, entry discriminare

- ↑ Inga Kristina Wobker / Linn Viktoria Rampl / Peter Kenning: customer envy - when differentiation turns into discrimination . brand 41. the marketing journal