Gift economy

The term gift economy (also “culture of gift giving” ) describes a sociological theory that is assigned to structural functionalism. The gift economy is therefore a social system in which goods and services are passed on without any direct or future recognizable (monetary) consideration, but actually mostly with delayed reciprocity . In the longer term, it is then a form of exchange that differs from barter - one speaks of the exchange of gifts as the opposite ofBarter . The gift economy is often based on the principle of general solidarity . Originally the term was used for a predominant phenomenon in prehistoric and tribal societies where social or immaterial consideration such as karma , prestige or loyalty and other forms of gratitude were expected. Anthropologists and other scientists have succeeded in demonstrating the exchange of gifts in contemporary cultures as well.

Origin of the term

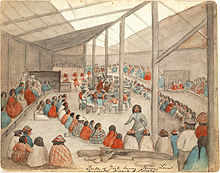

For the first time the term "gift economy" in is Marcel Mauss ' Essai sur le don (1923/24) mentioned in connection with the investigation of exchange and distribution of gifts among the Indian tribes of the Tlingit , Haida , Tsimshian and Kwakiutl in North America. Mauss has ethnologically examined the systemic importance of the exchange of gifts and established criteria according to which the exchange of gifts is fundamentally different from the exchange of goods . In gift shops, something in return is certainly expected, but it is usually not of a material nature and, above all, not formalized in the same way.

His best-known example is the potlatch , a periodically recurring festival of individual Indian tribes , at which the exchange of gifts got out of hand to compete for generosity and waste . Mauss assumes that the exchange of gifts is a basic social anthropological pattern and that the gift is both a relationship-building element and a way of manifesting social distance .

Bronisław Malinowski , who investigated the phenomenon of the kula exchange , which he discovered in the horticultural Trobrianders , comes to similar conclusions .

Definition of terms

The difference between the exchange of goods and gifts is partly explained by an opposing interpretation of “ goods ” and “gift”. The gift is discussed differently in the scientific community. Some scientists regard the gift as pure self-interest , others view the gift from the perspective of exchange theory, others in turn link the gift with economic calculation, which remains taboo. Sometimes the gift is interpreted as an intersection between self-interest and altruism and in the most extreme case understood as a gift without expectation of reciprocity and thus presented as an ideal .

Exchange of goods and gifts

Both the exchange of goods and the exchange of gifts each include a transfer, for which a consideration is expected. As already mentioned at the beginning, this consideration can also take place with a delay and be linked to events. When exchanging gifts, both the value of the consideration as well as the time of fulfillment are left to the recipient of the gift. An example of this delayed consideration is the invitation to dinner among friends. The consideration can also take place indirectly, that is, the recipient of the gift does not have to provide any consideration, but the donor receives recognition in the community through the award. The (partly former) unconditional hospitality of the Mediterranean, Arab, Persian and Indian peoples is regarded as an example of this.

Gift and trade

The gift transports - as the term is used - the signal of respect and reverence towards another person. In contrast, trade usually does not provide any external confirmation. The gift can be cheap, material, or symbolic. However, it is associated with costs , i.e. initially negative consequences of an action in view of a certain plan and decision-making area. But the gift is recognition , and recognition is a scarce resource . The scarcity of recognition is due to the limited availability of time and psychological energy. In this respect, the gift can also be understood as recognition as a form of consideration for something - i.e. in the sense of gratitude.

A strict separation of gift and commodity, as suggested by Marcel Mauss, is mainly based on the prevailing doctrine of his time and the underestimation of the dual nature of the gift and the exchange of gifts. For example, Maurice Godelier sees the gift as a combination of both, gift and commodity. The gift consists of the non-monetarily measurable gift and the monetarily measurable economic good . During the exchange, the exchange object or the recipient of the gift receives, in addition to the function of the exchange object, a special status and a special identity.

Older economic considerations

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, an intensive scientific discussion took place on the subject of the exchange of gifts. This was shaped by different understandings of the various areas of science. One side was represented by the economists, who in turn had quite different opinions among themselves, and the other side by the sociologists and philosophers.

Unity of morality and economy

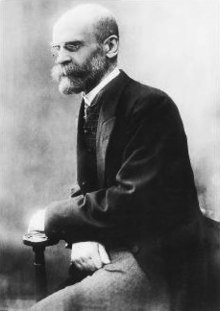

Viewpoints such as that of Bronisław Malinowski, who described gifts as a senseless form of exchange of goods and reported on forms of society that would offer an alternative way of life in contrast to the then dominant economic form in Europe, also served as a starting point for criticizing the principles, as did Marcel Mauss' remarks of rationalism and mercantilism . Mauss particularly criticized the fact that terms such as “individual” and “profit” are becoming increasingly important and that this not only harms society, but ultimately also harms the individual himself. Mauss' views in this area coincide with those of his uncle and teacher Émile Durkheim , the founder of empirical sociological science, who criticized the progressive separation of morality and economy and rejected the idea of individualism . With the criticism of individualism Durkheim joins the representatives of the historical school of economists , to which, for example, Gustav von Schmoller belonged and where Durkheim studied. The core idea of the historical school was the idea of a strict ethical understanding of the economy, i.e. a connection or unity of morality and economy. Karl Bücher also joined Schmoller as a critic of the existing economic structure, which was more and more geared solely towards regulated exchange. As an alternative, Schmoller and books proposed the transfer of services and goods in the unpaid sense. From this the implicit, moral obligation should then develop for the counterpart to also render services for the gifts received or to give away goods.

Total performance system

Marcel Mauss defines the exchange of gifts as a “système des prestations totales” (system of total achievement). This principle of the system of total performance is based on the fact that an exchange of goods and services does not take place in a strictly economic sense, but takes place voluntarily in the form of gifts and gifts. Mauss emphasizes in particular that this system is not just about giving (“thunder”) and accepting (“recevoir”) a gift, but also the response (“rendre”) as a third element of particular importance is.

More recent economic considerations

With the resurgence of the scientific discussion about the exchange of gifts in the 1960s to 1990s, the system of the gift economy was occasionally taken up again from an economic historical and economic theoretical point of view.

- From a behavioral point of view, the exchange of gifts contains two elements: firstly, the gain and benefit for the recipient of the gift and, secondly, the satisfaction and benefit from the giving of the gift for the giver. The efficiency of the gift exchange results from the combination of these elements.

- From a microeconomic point of view, the exchange of gifts corresponds to perfect price discrimination under monopoly conditions (Fig. 1).

Satisfaction cannot be measured (in monetary terms) and should therefore be seen as an immaterial benefit.

Exchange of gifts and perfect price discrimination

In the case of perfect price discrimination under monopoly conditions, the provider (the person giving the gift) receives the reservation price (the individual appreciation) from each customer (the person receiving the gift ). So he does not receive the market price , but the individual price on the demand curve . In other words, the individual appreciation of a gift by the recipient corresponds exactly to the price that he would be willing to pay at the most.

This also means that any profit comes from the monopoly (donor) and there is no consumer surplus. In a market economy , perfect price discrimination under monopoly conditions is rare. Because in order to be able to achieve this price discrimination, two conditions must be met: the monopolist must know the reservation price of each individual buyer and arbitrage must be prevented, i.e. resale and trade between the buyers must be excluded. The second condition for the exchange of gifts is given by the fact that every provider is a monopoly. This means that the recognition he gives is individual and cannot be given by anyone else; accordingly, it cannot be traded or resold. The first condition, knowing the reservation price, is a little more difficult to meet; It is assumed, however, that the recognition given approximates the needs of the recipient through individual experience and observations. When reciprocity occurs, the previous recipient of the gift, now the gift giver, again becomes a monopoly. This means that now all profit accrues from this. This repetitive reciprocity makes it possible for the two counterparties to alternately receive the producer surplus in the exchange of gifts and an efficient equilibrium is created. However, there remains uncertainty as to whether the gift will be reciprocated and how long the reciprocating process will last.

Exchange of gifts and trade

Avner Offer has investigated the interaction and the limits of the exchange of gifts and trading using the heuristic diagram opposite (Fig. 2). The abscissa (horizontal axis) measures the quantitative supply of a certain good (or all goods) within a market economy exchange (trade) or within an exchange of gifts. The ordinate (vertical axis) indicates the price (price equivalent). The figure contains two intersections of supply and demand , one for the market economy exchange and one for the exchange of gifts . In the case of the exchange of gifts , in contrast to the market-based exchange, both supply and demand functions are more price-inelastic , which means that supply or demand reacts disproportionately to price changes.

The section on the abscissa between to contains the goods or services that only the exchange of gifts can deliver (e.g. romantic love ). The vertical line is the market boundary and the market demand curve . Between and there is an overlap of the market supply curve and the demand curve of the gift exchange . This results from the fact that some goods or services are offered with or without recognition. The section would accordingly represent an authentic economy with an exchange of gifts and a market economy, and the straight line would represent the boundary between the exchange of gifts and the market economy. Above the limit of , the demand curve for the exchange of gifts runs downwards in the direction of the market equilibrium price . This part of the demand outside of the exchange of gifts is intended to make it clear that the exploitation of recognition in the process of selling as so-called "pseudo-recognition" can be useful for price discrimination. An example of this recognition would be business lunches. Here the handing over of a gift (the meal) takes place in the hope of reciprocity, here the conclusion of a contract.

The market economy marginal cost curve is more elastic (flatter) than the gift exchange supply curve . When productivity increases, it shifts to and the production limit to . This usually corresponds to the historical transformation from a pre-industrial society to one that is more market-oriented.

criticism

Criticism of the neoclassical analysis and classification of economic activity within a gift economy is predominantly expressed by anthropologists. The application of neoclassical models to archaic systems of economic activity and exchange usually requires an inappropriate and distorting objectification of immaterial relationships.

Sociological consideration

Marcel Mauss' work Essai sur le don is regarded as the starting point for the sociological examination of the exchange of gifts and the gift economy. As a sociologist and ethnologist , shaped by his teacher and uncle Émile Durkheim , who already gave a lecture on the subject of the exchange of gifts, Mauss succeeded in coining a general term of the exchange of gifts and establishing it in economic, legal, moral and sociogenetic science. However, his theses are mainly sociologically and culturally shaped. From the above-mentioned criticism of individualism, especially the representatives of the historical school, different sociological theories developed with regard to the social system of a gift economy and the motivation and reciprocity of the exchange of gifts.

Gift economy from a rationalist and utilitarian point of view

The assumption of rationality says that the rationalist acting individual chooses that alternative for given alternative courses of action, in which the value of the success of the action and the probability of the success of the action is greatest. From the rationalistic principle of action it was deduced that the exchange of gifts and trade are carried out in such a way that it corresponds to the individual benefit for each individual party. Since man is utility maximizer in utilitarianism , he has a natural aversion to situations of loss. Temporary losses, however, can be accepted if they lead to the establishment of a profitable cooperation.

The gift economy from a normativist and collectivist point of view

Pierre Bourdieu does not presuppose any explicit automatism (giving and reciprocating the gift by giving in return), since the uncertainty of the reciprocation must also be taken into account, but assumes that a large part of the gifts in a gift economy are reciprocated. According to his ideas, reciprocity is based on two principles: the time delay before a counter-gift is given, and the difference between the counter-gift and the first gift. If these principles are observed, a system emerges which, when given a gift, does not allow the gift in return to appear as something in return. That is, the gift will not be returned. The gift giver and the recipient - on the basis of the time delay and without negotiation - give their gifts out of generosity. According to Bourdieu, however, this is far from reality, and giving always includes taking into account possible strategic advantages. According to Bourdieu, the process of social gifting intentionally obscures reciprocity. He subjects the actors of the gift economy to an intentional, collective misunderstanding and concealment of the real facts: the conditions of an exchange, the implicit dependence of give and take.

The scientific investigations into blood donation stand against Bourdieu's theory . The blood donation is seen as the gift in its pure form, since the blood donor does not know the recipient and only receives symbolic compensation. Blood donation is therefore the classic example of altruistic behavior towards anonymous others in modern society .

The American sociologist Alvin W. Gouldner regards reciprocity as a moral norm that consists of two minimum requirements: "One should help those who have helped one and one should not offend those who have helped one." that - if this moral norm is internalized by actors in the gift economy system - this norm reduces the risk associated with giving a gift for the first time through the creation of trust and the creation of an obligation. Gouldner goes even further and differentiates between the motive level and the effect level. For example, the process of giving on the motive level can arise out of charity, but on the effect level it can have the unintended effect of reciprocal reciprocation.

Limits of the gift economy

The exchange of gifts can result in an obligation, in other words a debt . The giver receives an emotional and material benefit or advantage over the recipient through the gift . Through the one-time, but especially repeated, distribution of gifts, bonds arise in different forms: in the sense of a contractual obligation (financial) and in the sense of human bonds (emotional). This can go so far that the exchange of gifts leads the weaker party into constant hierarchical oppression .

A strong gift economy or an economic system that is predominantly based on reciprocity can displace the market and trade . As an example of this, anthropologists see social structures in which a regime of general reciprocity prevails, such as the Cosa Nostra in Italy, the Russian mafia and the triads in China.

Anthropological view

In anthropology , a distinction is also made between the two types of exchange: the market economy exchange and the exchange of gifts. The origin of the so-called anthropological "gift versus commodity" debate goes back to Marcel Mauss. Mauss challenged the view of free market advocates that human beings are driven by the pursuit of profit and that all human interactions and their motives can therefore be analyzed from an economic perspective.

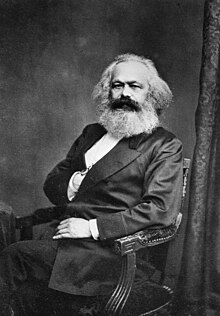

The idea that the exchange of gifts is an economic form that is opposed to the market-based exchange was propagated in particular by Christopher Gregory and Marilyn Strathern . Gregory sees the exchange of gifts as a personal relationship on the micro-social level, whereas the exchange of goods is part of trade and impersonal relationships. Gregory's assignment and differentiation criteria are based largely on the work of Karl Marx .

The sharp distinction between gifts and commodities introduced by Christopher Gregory has been repeatedly questioned and criticized by anthropologists over the past few years. The view of dividing it into two structures and thus differentiating between the socially anchored and culturally developed gift economy on the one hand and the impersonal, rational market economy on the other, is based on western, ethnocentric assumptions, the artificial formalization of the term "pure gift" of industrialized western society and the romanticization of the exchange of gifts in archaic societies.

Critics also state that Christopher Gregory's and Strathern's strict separation trivializes the exchange of gifts, but that gifts for industrialized societies are associated with very significant economic functions. For example, Christmas gifts are one of the most important economic drivers for retail in the United States . Furthermore, many examples can be found in Western societies that show characteristics of the gift economy, such as the exchange of knowledge in the scientific community and the free use of files and information on the Internet.

The anthropological consensus seems to be a compromise. The exchange of gifts and goods are not two completely different and mutually exclusive forms of society, but only two idealized types of exchange. In reality, every economic system is a mixture of both. The two types of exchange are intertwined and both components are often found in exchange situations.

Historical consideration of the gift economy

In principle, both historical and contemporary considerations show that the ideal of an economic system based exclusively on the gift economy system based on pure gifting, i.e. without any expectation of reciprocity, has neither existed in the past nor in the Present exists. Nevertheless, anthropologists repeatedly draw parallels with gift economy systems.

Gift economy in archaic societies

Probably the most cited and scientifically examined gift economy systems are the kula exchange and the potlatch. What these two phenomena have in common is that, in contrast to the pure gift in the sense of offering or sacrifice, they represent a social system, sometimes an economic system within an economic order .

Kula exchange

In the Trobriander kula exchange, in which valuable mussels are passed from person to person in a large ring over hundreds of kilometers , the relationship between each pair of trading partners is dyadic . This means that every exchange process is composed of two mostly opposing positions and consequently a balanced balance of the value takes place with every transfer. The value of Kulas results from the context of the production expended labor , the scarcity of the raw material and the particular history of the handover process, the predominantly adjacent with recurring annual visits to the trading partner Islands created.

The gifts that are exchanged in Kula are still necklaces (soulava) and bracelets (mwali) made but neither particularly rare materials a great craftsmanship have. Malinowski sees three important social functions in the kula exchange. Firstly, it serves to maintain friendly relations, peaceful contact and long-distance communication with trading partners between the inhabitants of the individual islands. Secondly, trade can also be connected with the Kula in the course of the annual expeditions and objects of daily use can be exchanged. Thirdly, Malinowski sees the kula as a consolidation and justification of the social status, which is characterized by the possession of the most valuable mussels.

Potlatch

Marcel Mauss not only saw the advantages of the gift economy, but also emphasized clearly that the gift economy system was destructive and could lead to ruinous competition. He cited the potlach as an example of excessive reciprocity. In the potlach, in which the exchange of gifts leads to competition for generosity and waste, he did not attribute the destructive character solely to reciprocity, but rather to the interplay of religious, economic, military, ethical and political factors.

Mauss sees two basic requirements as necessary for the gift economy to function in the Potlach. Firstly, a sufficient availability of natural resources to support life, such as fish and game , and secondly, a compact and hierarchical structure of society. The large surplus of food production of the tribes that organized the potlach made it possible for the upper class to be established , which did not have to be involved in the daily practice of food supply. Holding a gift festival enabled the establishment within the hierarchy and the acquisition of a higher status, which was manifested through titles. In the Kwakiutl tribes , for example, there were 651 titles that expressed a certain rank in the social hierarchy. However, potlatches were not mutually aligned and no one kept records of who gave a potlatch and how often. This was also due to the fact that it took place relatively infrequently and the occasions, such as the death of a chief, could not be foreseen.

Contemporary theses and developments

The exchange of gifts and the exchange of goods are not two completely different and mutually exclusive systems, but only two idealized types of exchange. In reality - according to the thesis - every economic system is a mixture of both.

Anthropological studies compare phenomena of today with the gift economy system and come to the conclusion that even today there are transfer payments that are not based on direct reciprocity, for example in the form of organ and blood donations, charity , file sharing and bequests . Most of the time nowadays the exchange of gifts takes place in the context of reciprocity .

For his analysis of the inner mechanisms of the open source movement, Gerd Sebald draws on an analogy to the gift economy of archaic societies based on the model of Marcel Mauss' research. He suggests that the hacker culture should be understood as a culture of exchange of gifts: the person who gives the community the greatest gifts enjoys the greatest respect.

The forerunners of today's free shops emerged in the late 1960s as part of the protest movements of the 1960s in the USA. The starting point was the criticism of money as a medium of exchange and idealized ideas. So the anarchist movement, the Diggers, founded a guerrilla theater group, among many other "free activities" such as the Free Medical Center , free stores in San Francisco and one in New York. In Australia, too, there was such a free store in Melbourne in the early 1970s , which also emerged from the anarchist movement and its criticism of capitalism . In 2010 they existed all over the northern hemisphere and in Germany in every major city.

See also

literature

- Marcel Mauss : The gift. Form and function of exchange in archaic societies . Suhrkamp, 2009, ISBN 3-518-28343-X , p. 208 (French: Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l'échange dans les sociétés archaïques (1925) . Lewis Hyde called the book The classic work on the exchange of gifts. ).

- Lewis Hyde : The Gift. Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property . Vintage, 1983, ISBN 0-394-71519-5 , pp. 328 (In particular Part 1: A Theory of Gifts ).

- Theodor Waitz : "Anthropology of primitive peoples" By Theodor Waitz, Georg Karl Cornelius Gerland, Georg Gerland. Published 1862.

- Frank Adloff, Steffen Mau: On giving and taking. On the sociology of reciprocity . Ed .: Jens Beckert, Rainer Forst, Wolfgang Knöbl, Frank Nullmeier and Shalini Randeria . tape 55 . Campus, 2005, ISBN 3-593-37757-8 , pp. 308 .

- Charles Eisenstein : The economy of connectedness, How money led the world to the abyss - and can still save it now . Scorpio, Berlin / Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-943416-03-9 (English: Sacred Economics - Money, Gift, and Society in the Age of Transition . 2011. Translated by Nikola Winter).

- Christian Siefkes : Contribute instead of swapping. Material production based on the Free Software model. AG SPAK books, 2008, ISBN 978-3-930830-99-2 , p. 186 ( peerconomy.org [PDF]).

Web links

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu: The Economy of Gifts. 1997 (English, monasticism in Buddhism )

- FreeeBay. ( Memento of March 30, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Dedicated to Gift Economy on the Internet (English, reviews and forum)

- The Digger Archives (English)

- Gift Economy (books and articles by feminist and peace activist Genevieve Vaughan )

Individual evidence

- ↑ David Cheal, "The Gift Economy" (1998), Routledge, p. 105.

- ^ A b c d A. Offer "Between the Gift and the Market: The Economy of Regard", The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 50, no. 3 (Aug., 1997), pp. 450-476

- ↑ Frank Hillebrandt : Practices of Exchange. On the sociology of symbolic forms of reciprocity . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften , Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-16040-5 , p. 94 ( limited preview in the Google book search [accessed on July 20, 2019]): "In order to develop a general concept of exchange, it must also be taken into account that the practice of exchange in contemporary society with the cultural-sociological reconstruction of the exchange of goods has not been adequately analyzed . "

- ↑ a b c R. Kranton: Reciprocal exchange: a self-sustaining system. In: American Economic Review. Volume 86, No. 4 (September), 1996, pp. 830-851.

- ↑ a b B. Malinowski, Argonauts of the western Pacific: a report on the ventures and adventures of the natives in the island worlds of Melanesian New Guinea . With a foreword by James G. Frazer. From the English by Heinrich Ludwig Herdt. Edited by Fritz Kramer, first published in 1922.

- ↑ Frank Hillebrandt : Practices of Exchange. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-16040-5 , p. 94 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed July 20, 2019]): "Because we not only buy or sell goods, but also exchange goods and services as gifts and presents."

- ^ Georg Müller-Christ , Annika Rehm: Corporate social responsibility as giving back to society? The exchange of gifts as a way out of the responsibility trap (= sustainability and management . Volume 7 ). Lit Verlag , Münster 2010, ISBN 978-3-643-10459-5 , pp. 58 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed July 23, 2019]).

- ↑ Dorothea Deterts: The gift in the network of social relationships. On the social reproduction of the Kanak in the paicî language region around Koné (New Caledonia) (= Göttingen Studies on Ethnology . Volume 8 ). Lit Verlag, Münster 2002, ISBN 978-3-8258-5656-4 , p. 22 ( limited preview in the Google book search [accessed on July 23, 2019]): "The concepts on which this opposition is based go back to the definition of goods by Karl Marx and the gift of Marcel Mauss, [...]"

- ↑ Georg Müller-Christ, Annika Rehm: The exchange of gifts as a way out of the responsibility trap . Münster 2010, ISBN 978-3-643-10459-5 , 4th theory of gift , p. 57 ff . ( Limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed on July 23, 2019]): "The concept of gift and the explanation for why people give something to others without receiving payment for it has been taken up and evaluated differently in different theoretical traditions."

- ↑ So z. B. the Hxaro system which was to be found both in the San of the Kalahari and in the Enga of Papua New Guinea . This involved an exchange of gifts with consideration in return, but this was only demanded if the circumstances (bad personal situation) existed. See: P. Wiessner: Connecting the connected : The inheritance of social ties among the Ju / 'hoan Bushmen and the Enga of Papua New Guinea , unpublished paper, Department of anthropology, University of Utah.

- ↑ J. du Boulay: Strangers and gifts: hostility and hospitality in rural Greece , J. Med. Stud., 1 (1991), pp. 37-53.

- ↑ A. Gingrich: Is wa milh: bread and salt. From the banquet at the Hawlan bin Amir in Yemen , communications from the Anthropological Society in Vienna, 116 (1986), pp. 41-69.

- ↑ M. Simpson-Herbert: Women, food and hospitality in Iranian society , Canberra Anthropology, 10, (1987), pp. 24-34.

- ↑ J. Pitt-Rivers: The stranger, the guest and the hostile host: introduction to the study of the laws of hospitality , in JG Peristiany, ed., Contributions to Mediterranean sociology (Paris, 1968), pp. 13-30.

- ^ S. Gifford: "The allocation of entrepreneurial attention", Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 19 (1992), pp. 265-84.

- ↑ DK Feil: The morality of exchange , in: George N. Appell, TN Madan: Choice and morality in anthropological perspective: Essays in honor of Derek Freeman , State University of New York Press, 1988, ISBN 0-88706-606-2 .

- ↑ Maurice Godelier: "Perspectives in Marxist anthropology" , Issue 18, Cambridge studies in social anthropology, Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 128.

- ^ Jan van Baal: Reciprocity and the position of women , Anthropological papers, Van Gorcum, 1975, pp. 54ff., ISBN 90-232-1320-3 .

- ↑ Cf. M. Mauss: The gift, form and function of exchange in archaic societies , Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Verlag, 6th edition, Berlin, 1990, pp. 135–147.

- ↑ E. Durkheim: On the division of social work, in. By Niklas Luhmann, Ed .: Franz v. Ludwig, Frankfurt, 1977, pp. 39-71

- ↑ See H. Winkel: The German National Economy in the 19th Century , Darmstadt, 1977.

- ^ Robert H. Frank: Microeconomics and behavior, McGraw-Hill Education, 1st edition, 1991, ISBN 0-07-021870-6 , pp. 393-395

- ^ P. Bohannan, G. Dalton: Markets in Africa. Evanston, IL, Northwestern University Press, 1962.

- ↑ K. Polanyi, CM Arensberg, HW Pearson: Trade and markets in the early empires. Glencoe, IL, Free Press, 1957.

- ↑ cf. B. Homans, GC: Sentiments and Activities: Essays in Social Science. Free Press, New York 1962.

- ↑ M. Sahlins: Stone Age Economics. Routledge Chapman & Hall, 2003, ISBN 978-0-415-32010-8 .

- ↑ M. Schmid: Rational action and social processes. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; ISBN 3-531-14081-7 , 2004, p. 221.

- ^ P. Bourdieu: Social sense. Critique of Theoretical Reason. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1987, ISBN 3-518-28666-8 (French 1980), p. 180 f.

- ↑ See RM Titmuss: The Gift Relationship: From Human Blood to Social Policy. Pantheon Books, New York 1971. - Interestingly, studies have also shown, for example, that the "quality" of blood donors decreases when the remuneration for donating blood increases.

- ↑ a b A. W. Gouldner: The norm of reciprocity . In: Reciprocity and Autonomy, Selected Articles. Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp, pp. 79-117, cit. 1 p. 98, cit. 2, p. 110.

- ↑ A well-known saying is “With gifts you make slaves” (German: “With gifts you make slaves”). See: RL Kelly: The foraging spectrum: diversity in hunter-gatherer lifeways. Washington, DC 1995.

- ^ M. Mauss: The gift: the form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. trans. WD Halls 1990 (first published 1925), p. 37.

- ^ F. Varese: Is Sicily the future of Russia? Private protection and the emergence of the Russian mafia. Archives Europeennes de Sociologies 35 (1994), pp. 224-258.

- ↑ M. Booth: The Triads: The Chinese criminal fraternity. London 1990.

- ^ DH Murray with Q. Baoqi: The origins of the Tiandihui: the Chinese triads in legend and history , (Stanford, 1994).

- ↑ D. Kaplan: Gift Exchange. In: Thomas Barfield (Ed.): The Dictionary of Anthropology. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford 1997, pp. 224-225.

- ↑ Christopher A. Gregory: Gifts to Men and Gifts to God: Gift Exchange and Capital Accumulation in Contemporary Papua. Man 15, 1980, pp. 626-652.

- ↑ Christopher A. Gregory: Gifts and Commodities , Academic Press, 1982, London

- ↑ Christopher A. Gregory: Savage money: the anthropology and politics of commodity exchange , Amsterdam, 1997, Harwood Academic.

- ↑ M. Strathern: Qualified value: the perspective of gift exchange. In: C. Humphrey and S. Hugh-Jones (Eds.), Barter, exchange and value: an anthropological approach. Cambridge, 1992, Cambridge University Press, pp. 169-190.

- ↑ Christopher A. Gregory: Gifts and Commodities. Academic Press, 1982, London, p. 12: “ Marx was able to develop a very important proposition: that commodity exchange is an exchange of alienable things between transactors who are in a state of reciprocal independence […]. The corollary of this is that non-commodity (gift) exchange is an exchange of inalienable things between transactors who are in a state of reciprocal dependence. This proposition is only implicit in Marx's analysis but it is […] a precise definition of gift exchange. "(German:" Marx was able to develop a very important statement: that the exchange of goods is an exchange of alienable goods between economic subjects who are in a state of mutual independence [...]. The logical consequence of this is that non-goods exchange [Gift exchange] is an exchange of inalienable things between economic subjects who are in a state of interdependence. This sentence is only implicitly found in Marx's analysis, but it is [...] a precise definition of the exchange of gifts. ")

- ↑ a b A. Rus: “Gift vs. commodity” debate revisited , Anthropological notebooks 14 (1), 2008, pp. 81-102, ISSN 1408-032X

- ^ A. Appadurai: Introduction: commodities and the politics of value. In: Arjun Appadurai (ed.): The social life of things. Cambridge University Press, New York 1986, pp. 3-63.

- ↑ JG Carrier: Gifts in a world of commodities: the ideology of the perfect gift in American society. In: Social Analysis. 29, 1990, pp. 19-37.

- ^ A b J. Parry: The gift, the Indian gift, and the 'Indian gift'. Man (ns) 21, 1986, pp. 453-73.

- ^ J. Parry, M. Bloch: Introduction: money and the morality of exchange. In: Jonathan Parry, Maurice Bloch (eds.): Money and the morality of exchange. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, pp. 1-32.

- ↑ David Cheal: The gift economy , New York, 1988, Routledge, p. 6

- ^ F. Bailey: Gifts and Poison , Oxford, 1971, Oxford Basil Blackwell.

- ↑ D. Miller: Consumption and Commodities , Annual Rev. Anthropology 24, 1995, pp. 141-64.

- ^ R. Hunt: Reciprocity , In: Thomas Barfield (Ed.), The dictionary of Anthropology. Oxford, 1997, Blackwell Publishing, p. 398.

- ^ M. Bergquist, J. Ljungberg: The power of gifts: organizing social relationships in open source communities. Info Systems Journal 11, 2001, pp. 305-320.

- ↑ P. Kollock: The Economies of Online Cooperation: Gifts and Public Goods in cyberspace. In: Marc Smith and Peter Kollock (Eds.), Communities in Cyberspace. London, 1999, Routledge, pp. 220-242.

- ^ N. Thomas: Entangled objects: Exchange, material culture, and colonialism in the Pacific , Cambridge, 1991, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ D. Miller: Alien Able gifts and inalienable commodities. In: Fred R. Myers (Ed.), The empire of things: Regimes of value and material culture. Oxford, England, 2001, Currey, pp. 91-105.

- ^ JG Carrier: Gifts and Commodities: Exchange and Western Capitalism since 1700. Routledge, London 1995, p. 9.

- ^ B. Malinowski: Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. 1922, pp. 95-99.

- ↑ H. Kovacic: Do ut des - An analysis of reciprocity and cooperation when exchanging on the Internet Saarbrücken: VDM, 2009

- ↑ Gerd Sebald: Open source as gift economy Gift economy in a vacuum

- ↑ Free shops (Local Economy Working Group, Hamburg)

- Jump up ↑ Free shops (Local Economy Working Group, Hamburg) ( Memento from September 23, 2009 in the Internet Archive )