Compressor (signal processing)

In sound engineering, a compressor is an effect device from the group of control amplifiers or a plug-in . It belongs to the group of dynamics processors and is used to limit the dynamic range of a signal.

functionality

By means of an envelope curve demodulator is derived from the level of a sound signal of a control voltage derived which is fed to a control element. In most compressors, a voltage-controlled amplifier influences the level of the signal to be processed. The dynamic progression is thus compressed , the volume difference between the quiet and loud passages is reduced.

- parameter

Typical, adjustable parameters of a compressor are

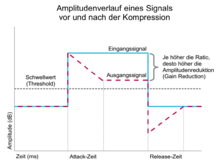

- Threshold : The Threshold ( threshold ) is determined, from which signal level at the compressor processes the signal.

- Ratio : This value describes the relationship between the rise in the uncompressed input signal and the rise in the compressed output signal above the set threshold. Example ratio 4: 1: If the input signal exceeds the threshold by 4 dB, the output signal only increases by 1 dB. From a ratio of 10: 1, one speaks of a limiter .

- Attack : Attack is the switch-on time / adjustment time of the compressor, calibrated in milliseconds, and thus the time that the compressor needs to reduce the output signal to typically 63% of the dynamic reduction set per ratio after the set threshold value has been exceeded.

- Release : Release is the switch-off time / settling time of the compressor, calibrated in milliseconds, and thus the time that the compressor needs to return the output signal to the unreduced level after it has fallen below the set threshold.

- Makeup Gain : With Makeup Gain , the level reduced by the set characteristic can be made up again so that the level peaks of the signal reach the same level as before. If the signal with its reduced dynamic range is increased in its entirety, then a higher loudness is achieved at the same volume . However, this can also increase the background noise and background noise contained in the signal ( noise floor ).

One of the most important, if not the most important instrument displays of a compressor is the optical control display of the amplitude reduction called Gain Reduction . On this display, calibrated in dB, the operator of a compressor can read how much reduction actually takes place in the signal path and how quickly the compressor regulates on and off.

Some compressors that are considered "classics", such as B. the models 1176LN from Urei , or LA-2A and LA-3A from Teltronix , do not have all of the above parameters. In the case of the latter, the ratio and threshold are linked to one another via the Peak Reduction control ; attack and release times automatically adapt to the signal material within a specified parameter range.

There are also compressors that have additional adjustable parameters, such as the idle gain in the classic analog from Orban.

Areas of application

Wherever overmodulation due to sudden jumps in volume is to be avoided, where differences between very quiet and very loud signal components are to be reduced (e.g. when processing a single vocal recording in a recording studio for better enforceability compared to the instrumental tracks), or where a consistent one Loudness of different signals that can be heard simultaneously or one after the other is required (e.g. at concerts , radio broadcasts or in discos ), compressors and, if necessary, limiters are used. Sound engineers or sound technicians usually install and use compressors in racks , musicians use them, depending on the instrument (e.g. electric guitar ), as a creative element in the effects chain in their rig .

A compressor is also used for the so-called night service on televisions, in which the low volume levels are increased slightly, but the overall signal level is reduced and, as a result, particularly loud passages are suppressed.

Compression of individual signals

Individual signals are compressed to smooth the overall dynamics and thus make quiet passages easier to understand (because they are louder), without loud passages appearing too loud or uncomfortable. For example, the human (singing) voice naturally has a high degree of dynamics, which makes it problematic in an unprocessed form to let the singing in a typical pop mix come to the fore over the remaining tracks. These level fluctuations can be compensated for using a compressor, which results in a constantly high average level and thus a significantly improved signal presence.

A compressor can also be used to comply with the technical limits when recording music (avoiding overmodulation, especially with digital recording). The dynamic of the original signal is limited before it is recorded.

Individual signals from percussive instruments, such as drums, are also compressed for targeted sound processing. By setting a longer attack time, the impact noise remains unprocessed and can therefore be set independently of the decay phase by turning the latter down using a suitably selected compression ratio.

Compression of sum signals

When compressing a finished piece of music z. B. imperceptible short-term level peaks attenuated. The overall signal can then be amplified without overdriving . The louder overall signal offers technical and psychoacoustic advantages.

This technology is often used in radio transmitters (typical device: Optimod ) in order to achieve the highest possible loudness and thus surpass that of background noises in cars, but also to achieve acoustic penetration compared to other transmitters. It is not uncommon for the often already heavily pre-compressed original signal of a piece of music to be compressed again before it is sent, which can lead to an audible negative change in the sound.

Compressors are also used in voice radio in order to be able to control the transmission power evenly and as high as possible, without driving the transmission amplifier into the non-linear distorting range.

Types

A basic distinction is made between broadband and multiband compressors . If the level of the entire input signal is processed evenly, it is called a broadband compressor. This type is often referred to as a single-band or single-band compressor , but this is technically imprecise as a single-band compressor can only work in a limited frequency range.

Broadband compressor

The broadband compressor circuit is by far the most common in sound engineering and comes e.g. B. is often used to give individual signals of a music mix more assertiveness and presence. However, broadband compressor circuits, due to their principle, reach their limits as soon as several dynamic curves run simultaneously in the input signal in different frequency ranges independently of one another, as is the case with a mixture of several individual signals. So z. For example, the use of a broadband compressor on a music mix means that an increase in level in the bass range leads to a weakening of the overall level of the mix (typical pumping when using the kick drum ).

Multiband compressor

Multiband compressors have been specially developed for level processing of such complex signals , in which the input signal is divided into several frequency bands by means of a crossover before the actual processing , each of which runs through one of several independent compressor circuits, the output signals of which are mixed together again after compression. In this way it is possible to condense complex and broadband mixed signals homogeneously without having to accept the unnatural mutual influence of different frequency bands.

Since multiband compressors can fundamentally intervene in the sound of a music mix and the complex parameterization requires a lot of experience with the operation and operation of the devices, there are attempts to automate the setting of the compressor. There are devices that can analyze the program material to be processed and, based on the spectral and dynamic properties, try to compress the material as homogeneously as possible. However, this gives the signal a certain sound aesthetic that does not always harmonize with the musical character of the material.

Even for smaller studios affordable multiband compressors have only been around since the advent of digital technology. The large amount of circuitry with a crossover and a compressor per frequency band makes analog solutions very complex.

Tube compressor

In contrast to compressors with semiconductor circuits , an electron tube is used as a reinforcing component in the tube compressor . Although both components have the same task, the tonal changes in the processed material can be very different, since, depending on the amplifier used, component and circuit-specific properties are incorporated into the sound material.

Optocompressor

With this type of compressor, the control voltage is fed to a light-emitting diode , the brightness of which changes accordingly. In the signal path there is a phototransistor or a photoresistor that performs the function of the control element. Particularly for the variant that works with the photo resistor, a certain sluggishness in the control behavior is characteristic, which is often perceived as particularly musical. The British sound engineer Joe Meek is often mentioned in the specialist literature as the inventor of the optocompressor .

Special forms

If an external signal is used instead of the original signal for control purposes, this is called "sidechain" or " ducking ". The original signal is turned down when the level of the control signal increases. A typical application is the automatic lowering of the music volume when the presenter or DJ makes announcements on the radio. This is why some DJ mixers have built in such a function directly ( talkover ). Some styles of club music use a volume pumping to the beat of the bass drum within certain passages of a piece of music as a stylistic device. In order to achieve this "ducking" effect, the signal from the bass drum (or, alternatively, a timeclock-controlled 4/4 pulse) is fed to the sidechain input of the compressor specially integrated for this purpose.

criticism

The excessive use of dynamic compressors both during the mixing and the transmission of music increases the loudness at the expense of the sound quality. This tendency is also known as the loudness war and has been criticized for years. Among other things, the magazine "stereo" criticized the compression of music titles in its 9/2010 issue. As an example, she compared the original CD edition with a remastered edition published later and found that remastering often overcompressed. The magazine interviewed Alan Parsons , who said: "It has become fashionable to compress too much. In terms of high fidelity, this is a disaster!"

In fact, the averaged volume level of today's CD productions is well above that which was still recorded in the 1980s and 1990s. At the same time, the dynamics in today's CD productions have dropped significantly. One of the world's best-known mastering engineers, Bob Katz, who also expressly speaks out against this trend, stated that many customers want this to be the case and that engineers who do not comply will lose their customers. In the meantime, however, it is becoming apparent that a rethink has begun. Some already see the Loudness War as history.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ books.google.de

- ^ David Miles Huber, Robert E. Runstein: Modern Recording Techniques . 8th edition. Focal Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-240-82157-3 . P. 497

- ↑ Interview, page 130

literature

- Thomas Sandmann: Effects and Dynamics. 7th edition, PPV-Verlag 2008, ISBN 978-3-932275-57-9

- Hubert Henle: The recording studio manual. 5th edition, GC Carstensen Verlag, Munich, 2001, ISBN 3-910098-19-3

- R. Beckmann: Manual of PA technology, basic component practice. 2nd edition, Elektor-Verlag, Aachen, 1990, ISBN 3-921608-66-X

- Roland Enders: The home recording manual. 3rd edition, Carstensen Verlag, Munich, 2003, ISBN 3-910098-25-8

- David Miles Huber, Robert E. Runstein: Modern Recording Techniques . 8th edition. Focal Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-240-82157-3 .

Web links

- How does the compressor work? Video workshop for beginners on the compressor

- Workshop compressors, limiters, de-essers

- Compressor basics on Bonedo.de