Roman villa at Lullingstone

At Lullingstone (east of London in Kent ) the remains of a richly furnished Roman villa have been excavated. Especially the fragments of wall paintings with Christian motifs aroused national interest.

location

The Lullingstone mansion is in a small valley near the Darent River . It is located on a slope and is particularly well preserved, as over the centuries earth slid down from the upper part of the slope and thereby also covered and protected the ruins of the villa.

History of the building

The first remains of settlements date from the time before the Roman conquest of Britain . There were shards and coins dating from AD 1 to AD 43. Remnants of buildings from this time have not yet been identified.

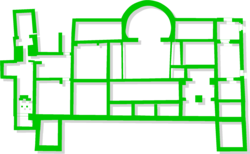

A first stone structure was erected here around 100 AD. This building is architecturally difficult to grasp because it has been obscured by later renovations. But it was certainly a simple portico villa with corner projections . The lower part of the building consisted of bricked-in flint stones . The structure was perhaps a half-timbered building. A cellar, which consisted of two rooms, remained in operation until the end of the villa. A kitchen building was built behind the villa (to the west).

The building was expanded between 150 and 180. A bath has been added on the south side. The basement had two entrances in the first construction phase, whereby one of these doors was bricked up in the second construction phase. The niche that was created was painted with the representation of three nymphs . The rest of the walls have also been painted, but little has survived. The redesign suggests that the basement has been converted into a cult room. The owner at the time seems to have been quite wealthy, at least he owned two marble busts, a rarity in the British province. They were found during the excavations in the basement. In the second century, a round building was also erected a little north of the villa. Its function is unknown, but it is believed that it was a small chapel.

In the third century, the entire Roman Empire experienced a period of economic decline. The villa appears to have been neglected, but it has not been abandoned, as the excavators suspected. Coins and shards indicate a settlement continuity. At the beginning of the fourth century a mausoleum was built west of the villa. It consisted of a central room around which there was a walkway. The building thus resembles a Roman-Gallic temple. In a pit in the central room were two lead coffins containing the skeletons of a man and a woman. There were numerous additions, including a bronze vessel, four glass bottles, two knives and two spoons. Noteworthy is a game board with 30 glass pieces that were placed on one of the coffins.

A granary was built next to the villa at around the same time. It was 24.4 x 10.7 m, making it one of the largest in Britain. The building had a raised floor to allow air to circulate underneath.

Around 350 the dining room of the villa received an apse and was furnished with a mosaic. Around 360/370 the owners seem to have converted to Christianity. One room was converted into a Christian chapel and received wall paintings with Christian motifs. These show the villa owner and his family in prayer, as well as the Christian Chi-Rho . Shortly after 400 the villa burned down and was never rebuilt.

The wall paintings

The villa owes its outstanding importance above all to the find of wall paintings from the fourth century. A few fragments of painting date back to the second century. A fragment was found in the bathroom that shows a fish. The fragment was found in the frigidarium , which may have been decorated with a seascape like that popular in baths. Other fragments still clinging to the wall show a simple field decoration. The niche in the cellar with the representation of three water nymphs also dates from the second century.

The paintings of the fourth century were found collapsed in the cellar and once adorned two rooms of a house chapel, the decoration of which can be roughly reconstructed. The best preserved wall is the west wall. The base is probably an imitation of marble. Above it there are six columns between which individual figures stand on a white background. The columns are framed by ribbons. The figures appear to be floating and have their arms spread out. Only one figure raises its right hand in greeting. The second figure from the left is the best preserved and is also highlighted by a curtain that has been preserved behind it. Except for the penultimate figure, all seem to depict men.

The east wall is poorly preserved and its reconstruction is difficult. The base zone is in turn occupied by imitation marble. Above is a field with six pillars. In the middle there is a circle with the Christian Chi-Rho. People seem to be depicted between the columns, walking towards the central field. The reconstruction of the third zone ultimately remains pure speculation; columns or ornamental bands could possibly have been here. Both decorative elements were found, but cannot be assigned to any wall with certainty.

The north wall shows the base zone with marble imitations and above it numerous columns, in the middle of which there was obviously a figurative scene. In the upper field there was a representation of a landscape with buildings.

The door of the room was in the south wall. To the right of her there was again a field with a central scene framed by columns above the base zone. There was a Chi-Rho in the upper field.

The vestibule was designed more simply, there was only a chi-ro on one wall, in a circle and framed by a geometric pattern.

The paintings are of particular importance as there is little evidence of Christian wall painting from the fourth century. So far they are unique in Britain. The style is simple to awkward. There are hardly any hints of light and shadow or perspective.

The mosaic

The mosaic in the dining room of the villa shows two scenes. In the actual apse the kidnapping of Europa by Jupiter is depicted as a bull. Europe, half-naked, sits on the bull. The scene is flanked by two erotes. The one behind pulls on the bull's tail and obviously tries to prevent the kidnapping. Above the scene there is a Latin inscription that translates as:

- If the jealous Juno had seen the swimming bull, then she would be restored to her side with greater justice in the houses of Aeolus

This saying is an allusion from the first book of the Aeneid , in which Juno, the wife of Jupiter, persuades the wind god Aeolus to kindle a storm in order to defeat Aenas on his journey to Italy. This scene clearly shows the high level of education of the villa owner.

The second scene of the mosaic shows Bellerophon as on Pegasus rides and the Chimera kills with a spear. This picture is framed by four round medallions in which there are in turn depictions in bust form of the four seasons.

Finds

A number of remarkable objects were found in the villa. First of all, there are two marble busts that were found in the cellar. Stylistically, they can be dated to the second century and are works from the Eastern Mediterranean. In previous research, it was often assumed that this was a father and son who owned the villa one after the other. The better preserved shows a bearded man in a military robe with a round fibula. However, a more recent theory says that the later emperor Pertinax and his father Publius Helvius Successus are shown here. Pertinax was governor of Britain before he was made emperor. Accordingly, the Lullingstonevilla was the governor's country residence.

Another find is a gem that shows the winged Victoria with a shield and in front of a breastplate that is part of a trophy. The gem is among the best ever found in Britain. It consists of carnelian . It has been argued that it was the amst seal of Pertinax when he was governor in Britain.

Excavations

The villa was discovered in 1939, although there have been speculations since the late eighteenth century that there are remains of a Roman building here. Excavations have been going on since 1949 and lasted 12 years. Today the villa is prepared for visitors.

Remarks

- ↑ Liversidge, in: meates: The Roman villa at Lullingstone , page 5, table 1, fig. 1 on p. 6

- ↑ Liversidge, in: meates: The Roman villa at Lullingstone , boards IV-V

- ^ Neal: Lullingstone, Roman Villa. , 22

- ↑ T. Ganschow / M. Steinhart: The Roman portraits from the villa of Lullingstone: Pertinax and his father, P Helvius Successus. In: Otium: Festschrift for Volker Michael Strocka. Remshalden 2005, pp. 47-53.

- ^ Martin Henig: The Victory-Gem from Lullingstone Roman Villa , in: Journal of the British Archaeological Association , 160 (2007), 1-7

literature

- Geoffrey Wells Meates: The Roman villa at Lullingstone, Kent. Vol. 1, The site. Kent Archaeological Society, London 1979, ISBN 0-85033-341-5 .

- Geoffrey Wells Meates: The Roman villa at Lullingstone, Kent. Vol. 2, The wall paintings and finds. Kent Archaeological Society, London 1987, ISBN 0-906746-09-4 .

- David S. Neal: Lullingstone, Roman Villa. London 1998, ISBN 1-85074-356-8 .

Web links

Coordinates: 51 ° 21 ′ 50.4 " N , 0 ° 11 ′ 47" E