Robert Wornum

Robert Wornum (born October 1, 1780 in London , † September 29, 1852 in London) was a piano maker who worked in London during the first half of the 19th century.

overview

Wornum became famous for his small pianos and the first high pianos, pianinos or “uprights”. He also devised a game mechanic for high pianos, which is the forerunner of all current game mechanics in pianinos and was used in Europe during the early 20th century. His piano manufacturing company was called Robert Wornum & Sons and still existed half a century after his death. The art historian Ralph Nicholson Wornum (1812–1877) was his son.

Life

Robert Wornum was born on October 1, 1780, the son of the music dealer and violin maker Robert Wornum (1742-1815), who worked in Glasshouse Street in London and later, after about 1777 in 42 Wigmore Street, near Cavendish Square. The piano historian Alfred J. Hipkins wrote that the young Wornum was to go into church service first, but in 1810 he was a foreman at the Wilkinson & Company music sellers at 3 Great Windmill Street and 13 Haymarket.

Wilkinson & Co. were the successors to Broderip & Wilkinson, a partnership between Francis Broderip and George Wilkinson that emerged in 1798 from the bankruptcy of the famous music dealers Longman & Broderip. Wilkinson & Co. was founded after the death of Broderip in 1807: According to the family history that the son Henry Wilkinson wrote about Broadhurst Wilkinson, the company was specially set up to complete tall piano cases, which the Astor and Leukenfeld companies under license after a Manufactured patent by William Southwell. Southwell is said to have built the first upright piano in 1790. He described that the piano was "designed to prevent it from being frequently out of tune" and without "any opening or perforation between the soundboard and sound post ", albeit with no the 1807 patent merely described a new arrangement of the dampers. The Monthly Magazine reported in May 1808 that Wilkinson & Co. offered the public "a new patent, a Cabinet-piano", and described that its shape "both unusual and appealing" was, and no more space claim as the smallest Bookcase, meanwhile its sound is both brilliant and gentle and its feel is "particularly light and enjoyable". He claimed that the strength and simplicity of its construction ensured that "the piano will hold its tuning longer than most other instruments". The Quarterly Musical Register described in the spring of 1812 that such instruments were also manufactured by other companies, and commented: "The time has to prove whether these pianos are preferred over the previous square pianos". Wornum's son Alfred later claimed that these instruments had not been very successful for a while, and Broadhurst Wilkinson admitted that the company had been required to provide warranty replacements for instruments that had already been sold when customers found that they "did not look particularly good" (did not keep the mood good). In any case, in mid-1809 the company announced in the " Times " that, as a result of the great increase in the production of their high pianos, they had decided to stop the production of all other instruments and to throw them on the market at half price in order to reduce inventory. and also offer favorable rental conditions for all pianos.

Wilkinson & Wornum and the unique high piano

According to Broadhurst Wilkinson, Wilkinson borrowed £ 12,000 ($ 53,000) in 1810 to form a partnership with Wornum and rented houses at 315 Oxford Street and Princes Street, adjacent to Hanover Square, for salesrooms, manufacturing workshops and apartments, with a garden behind 11 Princes Street where wood was dried.

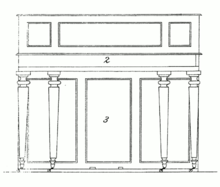

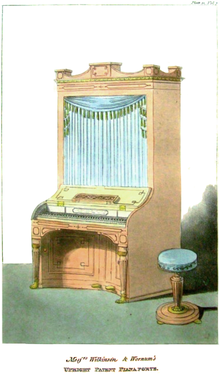

In 1811 Wornum had a small double-strung high piano patented, which was only approx. 99 cm high, and which he called "unique". Its strings were stretched diagonally from above to the right side of the case and acted on a small soundboard. The housing was divided into two parts for the keyboard and mechanics on the one hand, and for the strings and their frames on the other. Wornum's release acted directly on a flat nose (“padded notch”) on the hammer nut and was thus able to avoid the intermediate lever that had previously been found in many square pianos and in the upright pianos of competitor Southwell. The hammer did not return to the rest bar with its own weight or the weight of the intermediate lever or plunger, but by the force of a spring that was attached to the hammer bar. As with Southwell also used Wornum upper damper , which expressed on the strings above the hammers: they were suspended on levers, which had been stored at a separate bar, but the wires that they operated, were disposed on the back of the mechanism. Wornum also promoted a "buff stop," a device to lower the volume that was operated by the left pedal and dampened half the strings. Two articles from 1851 show that the company built a few hundred of these instruments.

One of Wornum's high pianos was featured in the February 1812 issue of The Repository of Arts under the heading "Fashionable Furniture," with a description that this type of piano is now in high demand because of the improvements it has made "brought these instruments a very high level of recognition". The short paragraph stated that the sizes ranged from 183 to 218 cm. They are available in mahogany and rosewood with brass parts, and their "unmatched" touch and the quality of their sound are praised - especially for instruments with two strings per tone, especially for vocal accompaniment.

Wilkinson & Wornum's manufacturing facility on Oxford Street was destroyed in a fire in October 1812. The owners announced in The Times just days later that the greater part of their completed inventory of pianos had been rescued, partly by neighbors, partly by volunteers, and that these pianos were still for sale at 11 Princes Street, but they started a collection to replace around seventy workers their lost tools without which they could not continue their work: in those years the tools were the private property of piano makers. At a November meeting of the company's lenders, Wilkinson's father, Charles Wilkinson, agreed that he would make no claims against them and guaranteed payments to other lenders, and in the spring of 1813 waived claims on his partners. Wilkinson & Wornum was dissolved on March 3, 1813. Wilkinson set up his own piano factory behind his new house at 32 Howland Street, and Wornum, who may have passed his patent to music seller John Watlen on Leicester Place, moved to 42 Wigmore Street.

Harmonic upright pianos and the even tension

In 1813 Wornum introduced a second high piano construction with vertical strings, which measured more than 137 cm, which he called "harmonic" and which are generally regarded as the first successful high pianos ( cottage upright ). Low, vertically strung pianos with similar properties were introduced in 1800 by Matthias Müller in Vienna and John Isaac Hawkins in Philadelphia and London. Hawkins instruments in particular included mechanics similar to that shown in the 1809 Wornum patent. The three highest octaves were made with a single string thickness, with the same tension and execution as in Wornum's patent of 1820, but both instruments were more unusual in sound and construction compared to the "Cottage Uprights". Müller's piano was described in the Oekonomische Encyklopädie , published in 1810, that it had a sound similar to the basset horn , and he offered a tandem model, which he called "Ditanaklasis", in contrast to which Hawkins' piano had a complete iron frame with an open back, a large, independent soundboard and bass strings in the form of helical springs (wound strings), it contained mechanical tuners, a folding keyboard and a metal upper bridge. Hipkins 'report of Hawkins' instrument in the 1890 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica describes that the instrument is "poor in sound".

In 1820 Wornum patented a system of equal tension for pianos (and "certain other stringed instruments"), which he described that could be achieved with "a single string thickness over anything", and for the shortened bass strings by changing the pitch of the windings or change the diameter of the wrapping. According to the patent report in Quarterly Musical Magazine , the intent was to prevent failure of the middle and upper octaves, which are a result of the usually different voltages and wire dimensions in the areas of a piano, and the author wrote that Wornum had succeeded in making a sound to produce, which is "solid, sonorous and brilliant, and his voice attitude justified the highest opinions about this construction principle". In any event, a report in the London Journal of Arts and Sciences predicted that "if it were ever to be put into use," it would "make a bad sound at the top of the instrument," and along with other objections, the rapporteur claims that it would be difficult to determine the string lengths by the methodes Wornums, and it was also difficult to produce and obtain strings of a single diameter.

Alfred Savage, who published several letters on piano construction in The Mechanics' magazine in the early 1840s , stated that this system offered the possibility of better tuning of the vocal position than any other, but that the tonal character would be inconsistent across the tone scale. He described that thicker wire produced desirable vibrations in the treble, but thinner wire produced better results in strength and fullness in the bass, and he added that the differences in stiffness were related to the length of the strings. Another piano correspondent, who signed as "The Harmonious Blacksmith", wrote in a letter in 1871 in the English Mechanic and World of Science magazine that his "deceased friend" Wornum had used the No.15 gauge wire across the scale , which in the 1820s and 1830s was at least four times as strong as the wire usually used at that time for the top notes and several sizes larger than that of much larger and longer grand pianos of that time, and he described that it was “a very good treble , but resulted in an extremely poor tenor and bass ”. Wornum used this scale (string layout) for at least the full duration of his patent, but it never came into general use.

Repetitions (“double actions”) and piccolo pianos

In 1826 Wornum had improvements patented, which he included in the patent application for professional pianos. He named a "pizzicato pedal" that is positioned between the two normal pedals and actuates connections that pressed the damper against the strings, further a single action , in which the damper levers were lifted by a button on an additional attachment of the tappet and two double actions with additional levers mounted on a second bar that operated both the dampers and the hammer catcher. The first of these was arranged like the mechanism from 1811, with a rear trigger on the button that operated the catcher (wire) lever; In the second, the catcher (wire) lever was activated by the ram. The plunger was attached to the underside of another lever, suspended from the hammer bar and carried the trigger. The release worked on the principle of the English mechanics for wings, with the regulation against the hammer bar, but with its spring mounted on the pusher instead of the lower part of the release. A fixed hammer return spring was not shown. Apparently, instead, a spring was mounted that acted on the hammer butt to prevent the hammer from "dancing when the key was released".

Two years later, Wornum patented an improvement to the tappets, which consisted of a button at the end of the lever that operated the extension of the lower lever to prevent undesired hammer movements after the strings were struck.

François-Joseph Fétis wrote in 1851 that he had played on two of Wornum's Uprights in 1829 and that they had significant (but not detailed) advantages over products from other manufacturers.

According to Hipkins, Wornum had perfected curved or "tied" double action that year. He introduced them in a “Cabinet” piano that was 112 cm high, and then in 1830 in the Piccolo Uprights. In this mechanism, a small ribbon attached to the butt of the hammer and attached to a wire on a lever axis performed the same function as the spring in the 1826 mechanism. The axle lever also operated a catcher that worked against an extension of the hammer butt and lifted the damper wire. This arrangement became known as tape check action , the same name as the modern piano action , which is designed differently in the shape of the tappet and the position and mode of operation of the dampers. Hipkins claims that the "easy touch achieved with the new action immediately attracted musical audiences," but that action was not in widespread use when the 1826 patent expired. He wrote around 1880 that its durability "made it a preferred model here and abroad" and predicted that this mechanism would likely replace the "Sticker Action" in England after it was already widely used in France and Germany be.

This mechanism was depicted as Wornum's double or piccolo action "in an article in Pianoforte magazine in the 1840s. The Penny Cyclopaedia (which R. Wornum named a contributor to the articles on pianos and organs) in which it was described as" The Invention by Mr. Wornum, patented for him about ten or twelve years ago ". A similar claim existed for the instructions for regulating the “double actions” in Wornum's piccolo, harmonic and cabinet pianos.

This is not the only published contribution to the origin of this mechanism, and in particular to the flexible ribbon or bridle tape by which it is known today. Harding explicitly described in the magazine The Pianoforte that Wornum "neither invented nor patented" the strap and attributed the invention to the piano maker Hermann Lichtenthal from Brussels (and later Saint Petersburg), who received a patent in 1832 for the improvement of a mechanism shows, which differs from the drawing of 1840 mainly in the shape and position of the damper lever and its mechanism. In 1836, the French piano tuner and later piano maker Claude Montal described in the magazine L'art d'accorder soi-même son piano that Camille Pleyel made improvements to the design of Wornums small pianos when he introduced the pianino in France in 1830. But although Montal describes the mechanics and the flexible ribbon in detail, he did not say whether these details were part of Pleyel's changes. Both examples of the use of a leather ribbon instead of woven material - which Harding explicitly attributes to Wornum - can thus be distinguished. Hipkins notes that the commercial success of Pleyel's pianos led to the "double action" being referred to as "French action" in England.

The mechanism has also been linked to Wornum's patent of 1842, although it is often dated to have been introduced by him five years earlier, obviously in relation to its description as a "tape check action" in the attached list the English patents for piano making in the 1879 edition of the History of the Pianoforte published in 1879 by piano maker and piano historian Edgar Brinsmead . In the 1870 edition it was named more precisely as "tape action".

Grand piano with double release and double action mechanisms

In 1830, Wornum rented buildings at 15 and 17 Store Street, Bedford Square for a new factory. In 1832 he opened a concert hall in house number 16, "built specifically for morning and evening concerts", with a capacity of 800 to 1000 seats.

According to the Encyclopædia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture and Furniture published by Loudon's , Wornum exhibited a piano in 1833 "which was almost indistinguishable from a library table." In 1838 he offered patented "double action" piccolo pianos at prices from 30 to 50 guineas , and "cottage and cabinet uprights" from 42 to 75 guineas ($ 350), which the encyclopedia as neatly crafted on the underside and "with the same grade." of sound and excellence ... as with the horizontal pianos (table pianos) "- the smallest and largest models are the" most frequently used "- just like 163 cm long pocket - and 237 cm long Imperial Grands for 75 and 90 guineas ($ 420) . He announced that these reduced prices were in response to the success of his piccolo piano, which "led certain manufacturers to build and sell similar instruments of a different character under the same name, thereby deceiving the public". The following year he offered several expensive versions of the larger models. The new six-octave “pocket” and the 6½-octave “Imperial” grand pianos followed the common practice of placing the strings above the hammers, but there was a completely separate support structure for the sound post, wooden frame, soundboard and bridges were all arranged above the strings, showing a rigid and uninterrupted construction similar to the upright pianos, just as they were later built in flapping grand pianos. These grand pianos were equipped with “tied double actions”, similar to those of the high pianos.

In 1840 Wornum had improved his grand piano by attaching a retaining spring to the butt of the hammer and the short end of the lever, with which he wanted to improve the repetition and "strengthen the forte game", but the inverse construction disappeared due to its unsatisfactory shape. Instead, Wornum turned his attention to the production of overstruck ("overstruck" or downstriking ) horizontal pianos ( grand pianos and table pianos), in which the hammers were arranged above the strings. In 1842 he patented the use of movable hammer return springs for flapping grand pianos and square pianos. Wornum included patent claims for a new arrangement of the folding rail and the trigger, and also for a method of operating the damper when pianing up by means of a leather strip that is attached either to the hammer butt or to a wire on the key.

Robert Wornum & Sons

At the World's Fair in 1851 Robert Wornum & Sons exhibited pianos ("cottage uprights") and double-stringed double-bowed grand pianos and table pianos, which were described as "invented and patented in 1842". Their Albion wing (semi-grand) became known as a good example of how a simpler and more economical construction without metal struts could be achieved with the overlapping mechanics. Wornum received an award for the improved “Piccolo Piano” - behind Sébastien Érard , Paris and London, who won medals for pianos, and on the same level as 22 other piano manufacturers, including John Broadwood & Sons , London, Schiedmayer & Sons, Stuttgart , Pape , Paris, and Jonas Chickering , Boston.

Robert Wornum died on September 29, 1852 after a brief illness. His son Alfred Nicholson Wornum succeeded him in the management of the piano factory.

The company exhibited at the 1855 World's Fair in Paris, but failed to win a prize.

In 1856, AN Wornum patented improvements to the overlapping mechanism, which consisted of a spring that ensured constant contact between the key lever and the pivot lever. Wornum also received a patent for a new arrangement of the regulating screw that made it easier to adjust and for a method of improving repetition using a spring. In 1862 further improvements were patented for Wornum, the aim of which was to substantially compact the mechanics by arranging the dampers under the hammers. The dampers were actuated by a plunger on the long end of the release lever. He also designed a folding mechanism for table pianos to keep them out of the way when not in use.

Robert Wornum & Sons exhibited pianos and grand pianos at the International Exhibition in London in 1862, as did their "folding" square piano. They received a medal for "Innovations in the invention of pianos" - one of almost 70 prizes that piano manufacturers such as Broadwood, Bösendorfer from Vienna, Pleyel, Wolff & Cie , Paris, and Steinway & Sons , New York received. They exhibited a “Piccolo Upright” at the Paris World's Fair “Exposition Universelle” in 1867, and also various moderately priced overturned wings without metal struts, where they received a bronze medal in the same class as J. Brinsmead from London, J. Pramberger, Vienna, and Hornung & Moeller, Copenhagen, among others, but below the level at which they had previously been rated at exhibitions.

In 1866, AN Wornum patented methods that made it possible to extend the soundboards beyond the soundpost bridge on pianos and flap grand pianos, which he claims improved the upper registers, and he patented further improvements to grand pianos in 187. Earlier that year Robert Wornum & Sons had announced that their "new patented construction" allowed a price reduction of over 100 guineas on grand pianos, as well as an assurance that these pianos would have "a full, sweet tone and a resilient touch" in 1871 The company offered four sizes, 168 cm and 259 cm, on the new production schedule, priced between 56 and 96 guineas ($ 260 to $ 450). In any case, a reporter for the Journal of the Society of Arts at the Second Annual International Exhibition in London in 1872 described the sound of the pianos with wooden frames as "sweet, but hardly full or forcible enough." (sweet, but hardly full or strong enough).

AN Wornum patented further improvements to grand pianos in 1875, introducing reversed-orientation hammers to accommodate longer strings in relation to the length of the case, and the company showed "under six foot" and "8 feet" long iron Grand Pianofortes "(" cast iron grand piano ") on his production schedule, together with a piccolo upright at the 1878 World's Fair" Exposition Universelle "in Paris, for which they received a silver medal. This again placed them on the same level as Brinsmead (although the company's founding was awarded a Legion of Honor medal on the same occasion ), as did Kriegelstein , Paris and Charles Stieff , Baltimore.

Hipkins wrote in an article on Wornum in the 1889 edition of the Dictionary of Music and Musicians that the current owner of Robert Wornum & Sons was Mr. AN Wornum , who followed his grandfather's ingenuity ”.

According to Frank Kidson, Wornum "continued to be a major player in the piano trade" in the early 1900s, but Harding said the company was last listed in the London address book as a piano manufacturer in 1900.

Individual evidence

- ^ David Crombie: Piano GPI Books, San Francisco 1995, p. 105.

- ^ The Musical Directory for 1794 p. 71, quoted in William Sandys and Simon A. Forster: The History of the Violin William Reeves, London 1864, p. 283.

- ↑ a b Alfred J. Hipkins: Robert Wornum. In: A Dictionary of Music and Musicians vol. 4. Macmillan & Co., London 1890, p. 489.

- ↑ Kidson identified Wilkinson's partner as organist Robert instead of Francis Broderip, who is listed in the firm's co-partnership notices in the London Gazette - Frank Kidson "Broderip and Wilkinson" British Music Publishers WE Hill and Sons, London 1900, pp. 18– 19th

-

↑ Thomas Busby , Concert Room and Orchestra Anecdotes of Music and Musicians, Ancient and Modern vol. III, Clementi & Co., London 1825, p. 206

In a promotional leaflet published on the occasion of the International Exhibition of 1862 and based on records from 1838, Broadwood & Sons claimed that the idea of a high piano in a sketch by James Shudi Broadwood dated 1804 . - ^ The Monthly Magazine. vol. XXV part 1, no. 4, May 1, 1808, p. 342.

- ^ Retrospect of the State of Music in Great Britain, since the Year 1789. The Quarterly Musical Register. January 1812, p. 26.

- ↑ AJ Hipkins: Cabinet piano. In: A Dictionary of Music and Musicians. vol. I MacMillan and Co., London 1890, p. 290.

- ↑ a b c Henry Broadhurst Wilkinson. Souvenir of the Broadhurst Wilkinsons Manchester 1902, pp. 24-27.

- ↑ advertisement. The Times. London, August 22, 1809, p. 1.

- ↑ the average exchange being given as 40 dollars to 9 pounds sterling; "Exchange - The United States of America" CT Watkins A Portable Cyclopaedia Richard Phillips, London 1810.

- ↑ a b Piano-forte Penny Cyclopaedia vol. 18. Charles Knight & Co. London, 1840, pp. 141-142.

- ^ Robert Wornum: An Improvement in the piano forte. No. 3419, March 26, 1811 Abridgments of Specifications relating to Music and Musical Instruments. AD 1694-1866. second edition. Office of the Commissioners of Patents for Inventions, London 1871, p. 66.

- ^ Rosamond Harding: The Piano-Forte. Gresham Books, Old Woking, Surrey 1977, p. 226.

- ↑ Harding, p. 230.

- ↑ piano collector CF Colt claimed this was a device to aid in tuning because the arrangement of the action prevented the strings to be muted off in the ordinary manner. CF Colt: The Early Piano. Stainer & Bell, London 1981, pp. 58, 118.

- ^ A b c Musical Instruments in the Great Exhibition London Journal of Arts, Sciences and Manufactures. vol. 39 no. 235 conjoined series, W. Newton, London 1852, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ a b "Fétis, the father", about the London exhibition Neue Berliner Musikzeitung. 5th year, no.44, October 1851, p. 347.

- ^ Messrs. Wilkinson & Wornum's Upright Patent Pianaforte. [sic] Plate 10. In: Fashionable Furniture. The Repository of Arts. February 1812 vol. 7 no.38, p. 111.

- ↑ To the Public - Dreadful Fire! In: The Times. October 13, 1812, p. 2.

- ↑ advertisement The Times. October 16, 1812, p. 1.

- ↑ advertisement The Times. October 27, 1812, p. 1.

- ^ The London Gazette. March 6, 1813, p. 489.

- ↑ advertisement The Times. November 11, 1812, p. 1; John Watlen was a composer, music seller and tuner, whose business at Edinburgh had failed 1798, and had set up on his own in London by 1807. By 1811 he advertised he had sold over 1,000 pianos, and offered newly patented six octave oblique pianos , "having superiority over all others, being only 19 inches deep", priced from 45 to as much as 80 guineas ($ 210 to $ 375) which he later indicated he "always had the advantage of the inventor of the above to superintend his manufactory" , and his advertisements published after the date of the fire at Oxford street state "the Patentee informs the Public, Merchants ..., & c. that the Oblique cannot be had any where else but at his house". Watlen's piano manufactory failed in 1827; his son Alexander Watlen later manufactured pianos in partnership with William Challen. - Frank Kidson "John Watlen" Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. vol. 5, The MacMillan Company, New York 1911, p. 438; advertisement The Times. September 5, 1811, p. 1; advertisement The Times. November 11, 1812; advertisement The Times. August 15, 1815, p. 1; advertisement The Times. February 28, 1823, p. 1; George Elwick The Bankrupt Directory ... December 1820 to April 1843. Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., London 1843, p. 433; The London Gazette. June 6, 1837, p. 1537.

- ^ Two early pianos also bear the nearby address 3 Welbeck street , occupied by booksellers C. and J. Ollier by 1817 - Arthur WJ Ord-Hume "Robert Wornum" Encyclopedia of the Piano. Taylor & Francis, London 2006, p. 427.

- ^ Daniel Spillane: History of the American Pianoforte. D. Spillane, New York 1891.

- ↑ Harding, p. 229.

- ↑ John Isaac Hawkins: Improvement in Piano Fortes. February 12, 1800.

- ^ "Specification of the Patent Granted to Mr. Isaac Hawkins, for an Invention applicable to Musical Instruments". November 13, 1800 The Repertory of Arts, Manufactures, and Agriculture , vol. VIII second series. J. Wyatt, London 1806, pp. 13-17.

- ↑ "Pianoforte" Economic Encyclopedia vol. 113. Joachim Pauli, Berlin 1810, pp. 9-20.

- ↑ Pianoforte. In: The Encyclopaedia Britannica , Vol. XIX, 9th edition. The Henry G. Allen Company, 1890, p. 75.

- ^ "Recent Patents." The London Journal of Arts and Sciences , vol.1, no.5. Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, London 1820, p. 340.

- ↑ Mr. Wornum's Patent The Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review vol. II, no. VII. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, London 1820, pp. 305-307.

- ↑ Recent Patents. The London Journal of Arts and Sciences , vol. 1, no. V. Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, London 1820, pp. 340-341.

- ^ Alfred Savage "Improvements in Piano-fortes". The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette , vol. XXXV no. 934 (July 3, 1841), pp. 22-23; Savage also described that pianos strung with graduated thicknesses of wire in the usual manner where the lower sounding strings were intentionally short to make their tension the same as the higher strings were more unstable than those with ordinary scales, adding later that if the lowest plain strings were excessively shortened, "no increase of thickness will compensate for want of sufficient tension, which produces a bad tone." - The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette vol. XXXVI no. 977 (April 30, 1842) London, 1842, pp. 345-349.

- ^ "Pianoforte Construction" The English Mechanic and World of Science vol. XIV no.353 December 29, 1871, p. 379.

- ↑ Malcolm Rose, David Law A Handbook of Historical Stringing Practice for Keyboard Instruments, 1671-1856 Lewes, 1991.

- ↑ Julius Bluethner, Heinrich Gretschel: Textbook of Pianofortebaues in its history, theory and technology BF Voigt Weimar 1872.

- ^ "The Harmonious Blacksmith": Improved Scale for the Lengths of Piano Strings, English Mechanic and World of Science , vol. XV, no. 372. May 10, 1872, pp. 202-203.

- ↑ a b c Harding pp. 169, 175b

- ^ Edward F. Rimbault The Pianoforte, its Origin, Progress, and Construction Robert Cocks & Co., London 1860, p. 181.

- ↑ Harding, p. 231.

- ^ "Recent Patents" London Journal of Arts and Sciences vol. 14, no.79. Sherwood, Gilbert & Piper, London, p. 358.

- ↑ a b Robert Wornum, Improvements in pianofortes. No. 5384, July 4, 1826 Abridgments of Specifications relating to Music and Musical Instruments. AD 1694-1866 second edition. Office of the Commissioners of Patents for Inventions, London 1871, p. 98.

- ↑ a b Lawrence M. Nalder The Modern Piano The Musical Opinion, London 1927, pp. 119-120.

- ^ Robert Wornum "Improvements on upright pianofortes" No. 5678 July 24, 1828 No. 5678 Abridgments of Specifications relating to Music and Musical Instruments. AD 1694-1866 second edition. Office of the Commissioners of Patents for Inventions, London 1871, pp. 107-108.

- ↑ advertisement The Musical World, new series vol. 2, London 1838, p. 299, reproduced by Harding, p. 398.

- ↑ Alfred J. Hipkins "The History of the Piano Forte" Scientific American Supplement No 385. Munn & Co. New York 1,883th.

-

↑ Liverpool piano maker commented in 1878 that the simpler and newly public domain Molyneux check action cost little more than a sticker action but required "considerably greater care in putting together."

"WH Davies " How to Make a Pianoforte "English Mechanic and World of Science vol. 27 1878, pp. 540, 589. - ↑ Alfred J. Hipkins "Piccolo Piano" A Dictionary of Music and Musicians vol.II, MacMillan and Co. London 1880, p 751st

- ↑ Alfred J. Hipkins "The Pianoforte" A Dictionary of Music and Musicians vol.II MacMillan & Co., London 1880, p 719th

-

^ "RN Wornum" is credited, separately, for Lives of Painters, Ancient and Modern; Roman, Tuscan, Venetian Schools, & c.

List of Contributors, The Penny Cyclopaedia vol XXVII Charles Knight and Co., London 1843, p. Vii. - ↑ Harding, p. 245.

- ↑ Analyzes des inventions brevetées depuis nov. 1830 jusqu'à Oct. 1840, et tombées dans le domaine public premiere série. Weissenbruch père, Bruxelles, 1845, pp. 9-11.

- ^ H. Lichtenthal, "Piano picolo" Belg. No. 538, Order no.113, reproduced by Harding, p. 247.

- ^ Claude Montal L'art d'accorder soi-même son piano J. Meissonnier, Paris 1836, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Philip R. Belt, including The Piano. WW Norton & Company , New York 1988, p. 44.

- ^ Edgar Brinsmead History of the Pianoforte . Novello, Ewer & Co. London 1879, p. 167.

- ^ Edgar Brinsmead History of the Pianoforte Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, London, p. 77.

- ^ The Wendover Estate: Counterpart leases and associated correspondence relating to nos. 15 and 17 Store Street, a piano manufactory and premises. Center for Buckinghamshire Studies ref. D 146/95, 1830-1837.

- ↑ Harding, p. 425.

- ↑ advertisement The Musical World no.IX May 13, 1836, p. 148; in 1879 the hall was described as seating between six and seven hundred, and cost £ 4 4s ($ 18.70) to rent, or £ 5 5s ($ 23.30) with the use of a piano - Charles Dickens, Jr. "Public Halls" Dickens's Dictionary of London. Charles Dickens & Evans, London 1879.

- ↑ a b Piano fortes. In: An Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture. vol. II, Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans, London 1839, pp. 1069-1070.

- ^ "Exchange - Great Britain" Michael Walsh The Mercantile Arithmetic, adapted to the Commerce of the United States Charles J. Hendee, Boston 1836, p. 186.

- ↑ advertisement The Musical World, new series vol. 2, London 1838, p. 299, reproduced in Harding, p. 398.

- ^ The Literary Gazette: and Journal of the Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, & c. No. 1163 Motes and Barclay, London May 4, 1839, p. 285.

- ^ JJ Kent: The Dining Room; The dwelling-rooms of a house. In: The Architectural Magazine, and Journal. cond. C. Loudon, vol. 2, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longman, London 1835, pp. 232-233.

- ^ Colt, p. 118.

- ↑ Harding, p. 246.

- ^ "Fig. 9. Mr. Wornum's new Grand Action" Penny Encyclopaedia. P. 141.

- ↑ Harding, p. 263.

- ↑ patent specification: The Record of Patent Inventions , W. Lake, London 1842, pp. 42-44.

- ^ "Additional List of Exhibitors in the Glass Palace." Daily News April 29, 1851, p. 2.

- ^ XA Class, Report of Musical Instruments, & c. Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851: Reports by the Juries on the Subjects in the Thirty Classes into Which the Exhibition was Divided. William Clowes & Sons, London 1852, pp. 333-334.

- ^ "Obituary" The Gentleman's Magazine , vol. 38, John Bowyer Nichols and Son, London 1852, p. 549.

- ↑ Deaths. In: The Times October 4, 1852, p. 7.

- ^ Ord-Hume Encyclopedia of the Piano. P. 427.

- ↑ List des Exposants, Angleterre et Colonies, Adrien de La Fage Quinze Visites Musicales à l'Exposition Universelle de 1855 Tardif, Paris, 1856, p. 201.

- ^ Ve Section: Pianos. Exposition universelle de 1855. Rapports du jury mixte international Imprimerie impériale, Paris 1856, p. 1364.

- ^ "Specifications of Patents Recently Filed" Mechanics Magazine vol.66, no.1754. Robertson, Brooman & Co., London 1857, p. 280.

- ^ Alfred Nicholson Wornum, An Improvement in the piano forte. No. 1148, April 19, 1862 "Improvements in pianofortes" Abridgments of Specifications relating to Music and Musical Instruments. AD 1694-1866 second edition. Office of the Commissioners of Patents for Inventions, London 1871, pp. 370-371.

- ↑ John Timbs: The Industry, Science & Art of the age: Or, The International Exhibition of 1862 Popularly Described from its origin to its close. Lockwood & Co., London 1863, p. 150; Robert Hunt: Handbook of the Industrial Department of the International Exhibition, 1862 vol. 2, Edward Stanford, London 1862, p. 133.

- ^ Class XVI Musical Instruments International Exhibition, 1862: Medals and Honorable Mentions awarded by the International Juries second edition George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, London 1862, pp. 217-221.

- ^ Frederick Clay: Report upon Musical Instruments (Class 10) - Pianofortes. In: Reports on the Paris Exhibition, 1867, vol. 2. George E. Eyer and William Spottiswoode, London 1868, p. 200.

- ^ "Groupe II, Classe 10 - Instruments de Musique" Exposition Universelle de 1867, à Paris. List of Générale des Récompenses Décernées par le Jury International Imprimerie Impériale, Paris 1867, p. 54.

- ↑ Alfred Nicholson Wornum, no.1,833 (provisional protection only), July 19, 1866 Abridgments of Specifications relating to Music and Musical Instruments. AD 1694-1866 second edition. Office of the Commissioners of Patents for Inventions, London 1871, p. 477.

- ^ Bennet Woodcroft Subject-matter Index of Patentees and Applications for Patents of Invention for the Year 1870 George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, London 1872, p. 291.

- ↑ advertisement The Times. June 27, 1870, p. 18.

- ↑ advertisement The Times. July 28, 1871, p. 15.

- ^ "International Exhibition, 1872" Journal of the Society of Arts vol. XX no. 1,038 (October 11, 1872) Bell and Daldy, London 1872, p. 890.

- ^ Catalog of the Special Loan Collection p. 164.

- ^ "Class 14 - Musical Instruments" Official Catalog of the British Section part I, second edition. George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, London 1878, pp. 65-66.

- ↑ Gustave Chouquet, "Rapport sur les instruments de musique" Exposition universelle internationale de 1878 à Paris. Rapports du jury international Imprimerie Nationale, Paris 1880, p. 34.

- ↑ Alfred J.Hipkins "Brinsmead" A Dictionary of Music and Musicians vol. IV MacMillan and Co., London 1890, p. 565.

- ↑ Gustave Chouquet Groupe II, Classe 13 Rapport sur les Instruments de Musique et les Editions Musicales Exposition universelle internationale de 1878 à Paris. Rapports du jury international Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1880, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Frank Kidson "Robert Wornum" British Music Publishers, Printers and Engravers WE Hill & Sons, London 1900, p. 156.

- ↑ Harding, appendix G, p. 425.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wornum, Robert |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English piano maker |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 1, 1780 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 29, 1852 |

| Place of death | London |