Russell's teapot

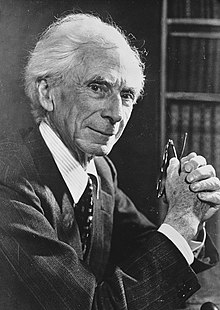

Russell's Teapot ( English Russell's teapot ) is an analogy that Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) in an article entitled Is There a God? served as a reductio ad absurdum . It should demonstrate that the burden of proof of an allegation rests with whoever makes it and in no way has an obligation to refute it . The article was commissioned by the London magazine Illustrated in 1952 and written but not published by Bertrand Russell. The article can ultimately be found in the estate both as a handwritten dictation (written by Edith Russell on March 5, 1952) and as a typescript .

Russell described a hypothetical teapot that orbits the sun in space between Earth and Mars and is so small that it cannot be found with telescopes. If he were to claim that such a teapot existed without further evidence, one could not expect anyone to believe him just because it was impossible to prove otherwise. Russell applied the analogy logically and philosophically directly to religions, comparing belief in the teapot with belief in God .

In 1958, Bertrand Russell used the same analogy again with a similar formulation. Since then, numerous philosophical and literary works on theism and atheism that have appeared since then refer to the analogy of the teapot. The analogy now referred to as “Russell's teapot” is often used in discussions about proof of God . Contrary to the original intention, atheists also used the teapot as a religious parody (teapotism) .

description

Bertrand Russell was born on May 18, 1872. His parents, who came from a noble family, wanted to protect their children from the influence of religion, which was seen as evil. His mother and sister Rachel (four years older than Bertrand) died in 1874. After his father's death in 1876, he and his brother Frank (seven years older) were raised by their devout paternal grandmother on science and social justice held progressive views and had a significant influence on him. Russell studied mathematics and is considered one of the fathers of analytical philosophy . He wrote a variety of works on philosophical, mathematical and social topics and was the driving force of the Russell Einstein Manifesto . In his essay Why I am not a Christian (1927; exp. 1957) he explains that religion is an evil, a disease that is primarily based on fear, the mother of cruelty, a slave religion that requires unconditional submission, the ancient oriental Tyranny comes from and is unworthy of a free person. In the article Is There a God? , commissioned by Illustrated magazine in 1952 (but ultimately not printed), Russell wrote:

“Many Orthodox pretend that it is the job of the skeptics to refute the given dogmas, rather than that of the dogmatists to prove them. That is of course a mistake. If I were to claim that between Earth and Mars there was a porcelain teapot orbiting the sun in an elliptical orbit, no one would be able to refute my claim, provided I would add, as a precaution, that this pot was too small to hold itself to be discovered by our most powerful telescopes. But if I went along and said that since my assertion could not be refuted, it was an intolerable presumption of human reason to question it, then one could rightly assume that I was telling nonsense. However, if the existence of such a teapot were affirmed in ancient books, taught as sacred truth every Sunday and inoculated into the minds of children in school, then doubting its existence would become a sign of norm violation. It would get the doubter in an enlightened age the attention of a psychiatrist or, in an earlier age, the attention of an inquisitor. "

In 1958 Russell used the analogy again:

“I should call myself an agnostic . But for all practical purposes I am an atheist . I don't think the existence of the Christian god is more likely than the existence of the gods of Olympus or Valhalla . To use a different picture, no one can prove that there is no porcelain teapot that moves in an elliptical orbit between Earth and Mars, but no one thinks this is likely enough to realistically need to be considered. I think the Christian God is just as improbable. "

analysis

Peter Atkins

The chemist Peter Atkins wrote in Creation Without a Creator that the core message of Russell's teapot is that there is no obligation to refute unsubstantiated claims. Occam's razor suggests that the simpler theory with fewer claims (e.g., a universe devoid of supernatural beings) should be the starting point for discussion rather than the more complex theory.

Richard Dawkins

In his books A Devil's Chaplain (2003) and Der Gotteswahn (2006), the ethologist Richard Dawkins used the teapot as an analogy to an argument against what he calls the agnostic mediation position , an approach of intellectual appeasement that allows areas of philosophy to to deal exclusively with religious matters. Science has no way of proving the existence or non-existence of a god. According to the agnostic mediator , therefore, belief and disbelief in a supreme being deserve the same respect and attention, for it is a matter of individual taste. Dawkins uses the teapot as a reductio ad absurdum of this position: If agnosticism demands that belief and disbelief in a supreme being be respected equally, it must respect belief in a teapot in orbit, since its existence is just as scientifically plausible as its existence of a supreme being.

Paul Chamberlain

The philosopher Paul Chamberlain countered that it was logically flawed to claim that positive statements bear a burden of proof and negative statements do not. He wrote that all allegations carry a burden of proof, including the existence of Mother Goose , the Tooth Fairy , the Flying Spaghetti Monster, and even Russell's teapot. It would be absurd to ask anyone to prove their non-existence. The burden of proof rests on those who claim that these fictional characters exist.

However, if real people were to be used instead of these fictional characters, such as Plato , Nero , Winston Churchill or George Washington , it would become clear that anyone who denies the existence of these people has a burden of proof that is in some ways greater than the burden of proof Person who claims they exist. Chamberlain argued that believing in Russell's teapot is not comparable to believing in God because billions of thoughtful and intelligent people are convinced of the existence of God.

Brian Garvey

The philosopher Brian Garvey argued that the teapot analogy with regard to religion fails because when it comes to the teapot, believers and non-believers simply disagree about an object in the universe, while all other beliefs about the universe can share, but not for atheists and theists apply. Garvey argued that it is not a matter of the theist claiming the existence of a thing and the atheist denying it - everyone has an alternative explanation of why the cosmos exists and how it came about: “The atheist doesn't just doubt an existence that the Theist affirms - the atheist also believes that God is not the cause of the state of the universe. There is either another reason for this or no reason at all. "

Peter van Inwagen

The philosopher Peter van Inwagen described the analogy as a fine example of Russell's rhetoric, but its logical argumentation was unclear, and if one wanted to make it more precise, it would prove to be inconsistent.

Alvin Carl Plantinga

In an interview with Gary Gutting for the New York Times philosophy blog The Stone , Alvin Plantinga said in 2014 that there are many arguments against teapotism . The only way to get a teapot into orbit around the sun is if a country with sufficiently developed rocket technology has put that teapot into orbit. No country with such capabilities wasted such resources; besides, one would have heard of such a process on the news. If one were to put belief in Russell's teapot on the same level as belief in God, there should be similar arguments against belief in God.

Eric Reitan

The philosopher Eric Reitan introduced belief in God in his book Is God a Delusion? the belief in Russell's teapot, fairies and Santa Claus . He argued that belief in God is different from belief in a teapot because a teapot is a physical object and therefore in principle verifiable . The main difference between God and Russell's teapot is that God stands for the ethical-religious hope of a fundamentally benevolent universe.

Similar analogies

Other thinkers have drawn up similar irrefutable analogies. John Bagnell Bury wrote in his 1913 book History of Freedom of Thought :

“Some people speak as if we were not justified in rejecting a theological doctrine unless we can prove it false. But the burden of proof does not lie upon the rejecter. I remember a conversation in which, when some disrespectful remark was made about hell, a loyal friend of that establishment said triumphantly, "But, absurd as it may seem, you cannot disprove it." If you were told that in a certain planet revolving around Sirius there is a race of donkeys who speak the English language and spend their time in discussing eugenics, you could not disprove the statement, but would it, on that account, have any claim to be believed? Some minds would be prepared to accept it, if it were reiterated often enough, through the potent force of suggestion. "

“Some people talk as if we don't have the right to reject an irrefutable theological teaching. But the burden of proof is not on the rejecter. I recall a conversation in which a disrespectful remark was made about Hell and a loyal friend of the institution said triumphantly, "But, as absurd as it may seem, you cannot refute it." If you were told that a particular planet orbiting Sirius had a breed of donkeys who speak the English language and spend their time discussing eugenics, you wouldn't be able to disprove the statement, but would that be from this one Reason credible? Some minds would be willing to accept it, if only it were repeated enough times, through the mighty power of suggestion. "

The philosopher Peter Boghossian commented on the statement: "You can't prove there's not a God." "You can't prove that God doesn't exist." in his book A Manual for Creating Atheists, the following counter-question:

"Do you believe there are little blue men living inside the planet Venus?"

"Do you think that little blue men live inside the planet Venus?"

About possible answers he wrote:

“If they say“ yes, ”then I change the color to yellow. I continue to change the color until they admit that not all the men I've described can physically live inside the planet. […] If they say “no,” I reply, “Why not? You can't prove it not to be true. " [...] If they respond, “I don't know,” to the question of little blue men living inside Venus, I ask them why they don't take the same stance with God and say, “I don't know. ” […] Finally, I ask, “What evidence could I give you that would prove God doesn't exist? Can you please give me a specific example of exactly what that evidence would look like? ””

“When someone says 'yes', I change the color to yellow. I keep changing the color until it is admitted that not all of the men I have described can physically live on the planet. […] When someone says "no", I answer: "Why not? You cannot prove that it is not the case." [...] When someone answers the question of the little blue men who live in Venus with "I don't know", I ask why he does not take the same attitude towards God and says: "I don't know". […] Finally, I ask: "What evidence could I give you that proves that God does not exist? Can you please give me a concrete example of what this evidence would look like exactly?" "

The astronomer Carl Sagan described a fire-breathing dragon in his garage in his book The Demon-Haunted World . If anyone wanted to see him, Sagan replied, the dragon was invisible. If you wanted to touch it, Sagan replied, the dragon was immaterial. If someone wanted to see his footprints, Sagan replies, the dragon would be floating. If one were to try to detect the fire with an infrared sensor , the response would be that the dragon would be heatless.

“Now, what's the difference between an invisible, incorporeal, floating dragon who spits heatless fire and no dragon at all? If there's no way to disprove my contention, no conceivable experiment that would count against it, what does it mean to say that my dragon exists? "

“Now what is the difference between an invisible, incorporeal, floating dragon that breathes heatless fire and no dragon at all? If there is no way to refute my claim, no conceivable experiment that would speak against the claim, what does it mean to say that my dragon exists? "

Carl Sagan questioned whether it makes sense to assume the existence of something when this existence has no (measurable) effects. At the same time he criticized the defensive attitude of the believers perceived by him to produce new explanations why God was not visible and could not be proven with other methods.

influence

The concept of Russell's teapot has explicitly influenced several religious parodies, such as the invisible pink unicorn and the flying spaghetti monster .

Rock musician Daevid Allen published with the band he founded Gong , among others, the album Flying Teapot , describing Russell's teapot in his book Gong Dreaming .

See also

literature

- Teja Bernardy: Project Zero. With zero religion to world peace - from religious ethics to secular autonomous ethics . 1st edition. Engelsdorfer Verlag, Leipzig 2016, ISBN 978-3-96008-483-9 .

- Peter W. Atkins: Creation Without a Creator . Rowohlt Tb., Reinbek near Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-499-18391-9 .

Web links

- The sense of nonsense atheism by other means author = Daniela Wakonigg. (No longer available online.) MIZ materials and information at the time, 2012, archived from the original on September 17, 2017 ; accessed on December 11, 2018 .

- The Religion of Teapotism. Logical Atheism Central, accessed December 11, 2018 .

- Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) Why I am not a Christian. (PDF) atheisten-info.at, accessed on December 11, 2018 .

- Yves Bossart : Should we believe in God? Thought experiment: teapot in space. Filosofix Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen, January 6, 2016, accessed on December 11, 2018 .

- Stephan Angene: The best and strongest argument against religion (s). (No longer available online.) December 31, 2012, archived from the original on October 20, 2018 ; accessed on December 11, 2018 .

Videos:

- Creation Without a Creator - How the Universe Organizes Itself on YouTube

- Russell's Teekanne - Criticism of Religion / by Christian Weilmeier on YouTube

- Criticism of religion / Feuerbach / Marx / Freud / Dawkins on YouTube

- Richard Dawkins - The Creation Lie and The God Delusion on YouTube

Individual evidence

- ↑ Yves Bossart: Should we believe in God? Thought experiment: teapot in space. Filosofix: The “Teapot” thought experiment. SRF , January 6, 2016, accessed on September 26, 2017 (article accompanying the Filosofix program on January 4, 2016 in SRF Kultur): “With the thought experiment, Russell wanted to draw attention to the fact that it is not the task of science, the existence of God to refute, but rather that the religions must show that God exists. "

- ^ A b John G. Slater with the help of Peter Kollner: Is There a God? In: Bertrand Russell Archives, McMaster University (Ed.): The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell . tape 11 : Last Philosophical Testament, 1943-68 . Routledge, London / New York 1997, ISBN 0-415-09409-7 , pp. 69 ff . (English, russell.mcmaster.ca [PDF; 89 kB ; retrieved on September 26, 2017] First edition: 1952).

- ^ Fritz Allhoff, Scott C. Lowe: Christmas - Philosophy for Everyone: Better Than a Lump of Coal . John Wiley and Sons, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4443-3090-8 , chap. 5 , p. 65-66 (English, 256 pages).

- ↑ a b c d Brian Garvey: Absence of evidence, evidence of absence, and the atheist's teapot . Ed .: Ars Disputandi . 10th edition. 2010, p. 9–22 , doi : 10.1080 / 15665399.2010.10820011 (English, tandfonline.com [PDF]).

- ^ Andrew David Irvine: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, accessed January 1, 2015 .

- ↑ The Peerage: John Francis Stanley Russell, 2nd Earl Russell. Retrieved September 18, 2016 .

- ↑ Bertrand Russell's Father. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011 ; accessed on September 22, 2017 .

- ↑ Brian Leiter: “Analytic” and “Continental” Philosophy. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on November 15, 2006 ; accessed on September 22, 2017 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Götz Neuneck , Michael Schaaf (Ed.): On the history of the Pugwash movement in Germany. Publication by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science , Berlin 2005.

- ^ Bertrand Russell: Why I Am Not a Christian (1927). Retrieved September 21, 2017 .

- ↑ Peter W. Atkins : Creation Without a Creator . Rowohlt Tb., ISBN 978-3-499-18391-1 .

- ^ Peter W. Atkins : The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Science . Ed .: Philip Clayton, Zachary Simpson. OUP Oxford, 2016, ISBN 978-0-19-954365-6 , pp. 129-130 (English, 1023 pp., Books.google.com - Atheism and science).

- ↑ Richard Dawkins : A Devil's Chaplain . Houghton Mifflin, 2003, ISBN 0-618-33540-4 (English).

- ^ A b Richard Dawkins : The God Delusion . Houghton Mifflin, 2006, ISBN 0-618-68000-4 (English).

- ^ Paul Chamberlain: Why People Don't Believe: Confronting Six Challenges to Christian Faith . Baker Books, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4412-3209-0 , pp. 82 (English, books.google.com ).

- ↑ Dariusz Lukasiewicz, Roger Pouivet: The Right to Believe. Perspectives in Religious Epistemology . Ontos, 2012, ISBN 978-3-86838-132-0 , pp. 15 ff . (English).

- ^ Gary Gutting: The Stone - Is Atheism Irrational? The New York Times, Feb 09, 2014, 2014 (English, opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com ).

- ↑ Eric Reitan: Is God a Delusion? Wiley-Blackwell, 2008, ISBN 1-4051-8361-6 , pp. 78-80 (English).

- ↑ John Bagnell Bury: History of Freedom of Thought . Prometheus Books, London 2007, ISBN 978-1-59102-519-1 , pp. 11 (English, books.google.ie - first edition: Williams & Norgate, 1913).

- ↑ Carl Sagan: The demon-haunted world. Science as a candle in the dark . Random House, New York 1995, ISBN 978-0-394-53512-8 , pp. 171-173 (English).

- ^ Gary Wolf: The Church of the Non-Believers . Wired News, November 14, 2006 ( wired.com ).

- ↑ genius.com