Slavery in West Africa

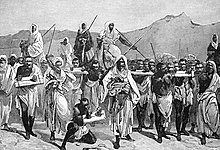

The slavery in West Africa was established socially and in almost all historical cultures. Unless otherwise stated, the presentation of the situation in this article refers to the historical social system of the Akan on the Gold and Ivory Coast of West Africa. In West Africa there was a differentiated classification of different types of slaves with partly hierarchical structures within slavery , which are explained below.

In addition, one differentiated the slaves in so-called Twi designations : first generation slaves were called Nnonum if they were prisoners of war and Nnonkofo if they were bought slaves. The latter were also called Odonko (Sing.) In Asante . Second generation slaves were divided into male Ahenemma and female Ahenenana . These were the children or grandchildren of a ruler or chair holder when the mother was not free.

State slaves

All state slaves belonged to the chair , that is, to the state or king. If they weren't sold on, they were mostly only used for government purposes. In the case of prisoners of war and tribute slaves, these were mainly sacrificial purposes. The state slaves included all foreign slaves who belonged to one of the following categories:

Prisoners of war

( Twi Nnonum ) These had been captured on campaigns and raids.

Tribute slaves

(Twi: "Akwa" or "Ahoho") These came from tributary tribes and were sent as tribute by their tribal chiefs.

Sold children

(Twi: “Nyafo”) This included all those slaves who had been sold into slavery abroad by their families as children. They remained slaves for life with no hope of release.

Household slaves

(Twi: "Fie-nipa") Household slaves among the Akan of the Gold Coast were all those who had voluntarily entered into slavery, mostly due to debts of their own or that of their families, in order to settle their debts in the form of services or because they were out had to flee their previous environment. Sometimes such slaves were also confiscated by their “benefactors” (Twi: Odefu ) to settle a debt.

Typically, household slaves served their benefactors as personal followers, mostly as bodyguards, personal assistants, and the like. Unlike other slaves, however, they had a non-transferable status, so they could not be resold. They were considered "born free" and were viewed as compatriots. The relationship between slave and benefactor in such cases was mostly of a very personal nature and existed until the debt was settled or the reason for flight was no longer given.

A distinction was made among the household slaves (the Twi term "Fie-nipa" actually stands as a general term for "unfree domestic workers") the following groups:

Debt slaves

(Twi: "Asomfo") Debt slaves were those who were left by their families to pay a debt to the creditor.

Escape slaves

(Twi: "Aweafo") Escape slaves were all those who voluntarily entered slavery in order to escape their families or their access. However, the classification as an escape slave presupposed the benevolence of the Odefu. Usually this benevolence was a show of respect for a friendly or influential family. The slave status that this gave them gave them a certain inviolability to outsiders. In all other cases, however, refugees seeking protection were considered family slaves (see below).

Okra slaves

(Twi: Okra, Okrafo, Okra-Manu, fem .: Okrara; however, in the fetu of the 17th century, “Ografo” was also the name for a woman who was cast out by her husband)

Okra is the name of the best and most trustworthy friend of a person for both the Akan and the Ewe in West Africa. Such a person was usually chosen from among the slaves and solemnly elected to this position in connection with a major festival. An okra slave was treated far better than the other slaves, he shared all the joys and sorrows with his owner, he helped the owner carry out his or her plans and mostly also had the supervision of everything that the benefactor owned . Okra slave and master or okra slave and mistress were considered to be one and the same person. The name comes from the fact that the okra slave was destined to stay at his side as a constant companion , like a second "okra" - Kra means "life soul". He shared the fate of his master in every respect, which also meant that in the event of his master's death he was sacrificed in order to be able to serve his earthly master in the world of the dead.

There are also the okra slaves called "okrakwa" in the Twi language, but in the past only a king was allowed to keep them. You always had to be around him and be ready at once at every hint he made. They represented a special group of royal slaves.

Family slaves

(Twi: "Otutunafu") Family slaves were private house slaves who, as a result of poverty or dangerous circumstances, had voluntarily entered into slavery. Most of the time this only affected a single person, but sometimes entire families would commit to a benefactor. This was sometimes done in the settlement of a debt, but mostly for reasons of poverty to maintain the basic necessities of life. Family slaves on the Gold Coast were always regarded as Dihi , as “free citizens”, as well as compatriots of their master, or at least they were treated as equal to the compatriots of their benefactor. During their slavery they also formed part of their Odefu's family. Family slaves usually did the menial housework, working in the fields or in the garden. In general, they were treated well and were mostly allowed to work for themselves on the side and keep what they earned. They were even allowed to keep slaves themselves, that is, families who voluntarily entered slavery could bring their own slaves with them and keep them.

Under the Akan there was a rule that spouses were allowed to own property separately from each other. Consequently the slaves could belong to a master or mistress. This point becomes particularly important when these slaves had children. The children of slaves also remained slaves belonging to the family of their parents' owners.

As part of the colonial legislation, the British on the Gold Coast issued the Marriage Ordinance or Ordinance No.14 of 1884 , u. a. also marriage rules, under which the special position of family slaves was taken into account. It was regulated that although slavery had actually been declared abolished by the British, family slaves were tolerated insofar as they could form part of society, provided that the slaves concerned were satisfied with their lot. In general, the British authorities found that very rarely did family slaves run away from their benefactors to seek protection with the UK District Commissioner , who guaranteed runaway slaves freedom in any event. It should be also mentioned that the British in their early colonial period, the usual form of marriage in West Africa of concubinage saw as slavery.

Pawn slaves

(Twi: "Ahuba" or "Awowa" (pawn slaves) and "Akoa-paa" (persons condemned to temporary slavery))

Pledge slaves were slaves who had to serve their benefactors until they were redeemed or a debt (including interest) had been repaid through work. Her slave status was therefore only temporary. The same was true of people who had been sentenced to a temporary slave state by a court.

Such a pawnbroker worked for his pawnbroker like a family slave, that is, he tilled the soil, did household chores, was sent out to fish, etc., with the difference that he did not belong to the pawnbroker's family, but continued to belong to the pawnbroker's family . A slave with a temporary slave status could not be sold outside the communal community, but could be sold to another family in the same place. Sometimes a pawnbroker was given money so that he could do any kind of trade in order to be able to pay off the pawn debt with the profit made. This was common in Denkira and Assin in the 19th century, but not in the coastal towns of the Gold Coast.

Regarding family ties, a man could punish his sister's child and lease or sell him as a slave to pay off his own debts, since that child would one day be his legal heir. However, he could only do this with his heirs (mother right), but in no case with his own children, as these (in most forms of marriage) belonged to their mother's family. A child of his brother was also taboo in this case. In general, pledging children required the consent of the relationship to which the child belonged according to the type of marriage. In addition, a brother could lease his own brother, but then only in the settlement of a family debt and then only in the event that there were no nephews or nieces. However, there was still the restriction that a younger brother could never lease his older brother, only the other way around.

In the case of a female pawn slave, the pawnbroker was strictly prohibited from taking her as his concubine. If he had nevertheless entered into a connection with her, whether by force or voluntarily was irrelevant, the guilt was immediately considered extinguished and the slave was free and could return home. The same also applied to the use of excessive physical violence, if it was viewed as inappropriate or unjustified. These relatively modern slave rights seem to have developed under European influence in the 19th century.

If a state of debt persisted for years with no prospect of repayment, however, in the case of a female slave, the pledgee was given the right to make her his concubine. If the pawnbroker gave birth to her master, the amount claimed back increased not only by the usual 50% interest on the original amount, but also by 4½ ackies (16 ackies = 1 ounce of gold) for each child as an allowance for their maintenance. Often the pawnbroker families felt compelled to borrow the money to buy the woman and her children elsewhere, which initially abolished serfdom, but gradually increased the debt to an extreme level, so that entire families settled down after one or two generations found themselves in a state of hopeless serfdom. With the death of a pledged person, the debt was by no means extinguished, in such a case the debtor had to give another pledge or pay off the amount originally owed, although the interest was sometimes waived.

The British, at least in the 19th century, viewed this pledge system as an even worse social institution than that of actual slavery, since it irrevocably brought not only individuals but entire family clans into a state of eternal serfdom. This was particularly the case with pledges for loans provided. After taking over jurisdiction in the Fanti Confederation , the UK authorities refused to consider a loan as anything other than any other debt. As a result, the chances of getting out of the state of eternal serfdom or not getting into it in the first place were significantly better than before for many families, because other laws also applied to the Fantis to settle any other, ie non-monetary debt .

"Macrons"

Macrons, especially in the 17th and 18th centuries, were those slaves who were singled out by European slave traders as "unworthy" or "unfit". The ship's captains or, on their behalf, the ship's doctor or ship's barber also made a precise selection and assessment when buying slaves. At the end of the 17th century in Whydah all such slaves were classified as "Macrons" (Bosmann), who were older than 35, had mutilations, who were missing at least 1 tooth, had lines over their eyes (the tribal symbol of a certain nation) or which were sick.

Sacral or cult slaves

Sacral or cult slaves were slaves who belonged to a particular temple, oracle or other religious location and who mostly performed the necessary work to maintain the place of worship, to support the cult activities or whatever the bearers of religious titles ordered them. In the past, such slaves rarely had to be acquired; most came voluntarily. This was due to the fact that the bearers of religious titles generally also enjoyed a certain immunity in terms of person and property and they could delegate this immunity to third parties. In particular in the case of court proceedings, until a judgment had been passed or also at the voluntary request, the person concerned was handed over to the religious title holder as a slave for the protection of person and property. The reasons for this could be of very different nature for the individual, whether wrongly accused or not, in each case they enjoyed temporary protection until a specific matter was resolved. In any case, the religious titleholders were encouraged to mediate in order to avoid the need for an elaborate courtroom. If it was necessary to extend the granting of immunity in the long term, this was only possible with the surrender of freedom for life; a transfer back to the status of a free person was usually not provided, since officially a sacred slave was considered the personal property of the deity for whom he was became active. Depending on which religious title the title holder was, these sacral slaves were then also slaves of the respective title or secret society that had awarded this title.

Special features in Kano

Royal slaves

In general, slaves, especially in the Islamic societies of West Africa, were considered worthless creatures that were not viewed as fully-fledged human beings. In the special case of the Hausa in Kano (Northern Nigeria) the class of royal slaves was added. With these royal slaves, which belonged directly and personally to the Sarkin (king, later: Emir) of Kano, a distinction was made between Bayi = slaves of the first generation and Cucanawa = those who were already born as slaves. Within the Bayi slaves, the Baibayi were also delimited , ie "the doves", by which all those first generation slaves were understood who could not (or not yet) understand or speak the Haussa language. It was a kind of "elite slave", whose most deserving representatives were sometimes rewarded with one or the other important office that was associated with specially created slave titles. In some cases, the emirs and the royal slaves had already played with each other as children, as both the mother of the emir and that of the royal slave children had belonged to the harem of the previous emir. The loyalty of these slaves to their emir was hardly called into question even in the case of larger slave revolts.

Slave title of the royal slaves

There were some special offices that were reserved exclusively for representatives of the royal slaves in the Kanos state apparatus in the 19th century. This included the Dan Rimi . This was the slave who in Kano had the honor of being able to crown a new emir, that is, he carried out the actual enthronement ceremony. The real kingmakers were of course free nobles, although when drawing up a list of candidates, at least towards the end of the 19th century, the "Dan Rimi" was also consulted. The Caliph of Sokoto himself then decided on the appointment of a new Emir. The emirate of Kano has been part of the Sokoto Caliphate since it was founded in 1809. The Shettima fulfilled another special office . This was the commander of a special rifle division formed from the ranks of the royal slaves. There was also the shamaki . He was responsible for overseeing the palace budget and its staff, including the emir's stables and horses. He lived in a special property within the palace complex.

Eunuchs

Eunuchs played an important role among the royal slaves in Kano . Some of the slave offices were, at least in theory, reserved only for eunuchs. Kanos eunuchs were mostly bought in special centers in which one had specialized in their "production". There was one near Kano , as well as in Baguirmi and Nupe . Because of their social ostracism, eunuchs were particularly dependent on the rulers they served and consequently particularly closely related to them. Therefore, they were granted access to numerous roles that would otherwise only have been occupied by privileged people from the royal family. However, this concerned z. B. not only the bodyguards of the royal concubines, but above all military services at the highest levels, since the rulers could be sure of a special loyalty with them. Supervision of the palace eunuchs and the yan bindiga , the palace guard, which was made up of slave shooters , was the responsibility of the sallama in Kano , who did not necessarily have to be a eunuch himself.

Slavery and "Honor" in Islamic West Africa

Slaves, including royal slaves, officially had no honor in Islamic societies ( Hausa : Martaba ). Their status as slaves meant that they lived apart from the general code that governed the life and status of a free person within the framework of kinship, family and religion. Once in slavery, social norms resulting from kinship or religion could be completely ignored. All slaves, royal or not, were exempt from all social rights, including rights over their own bodies and sexuality, but they were also exempt from the duties, constraints and responsibilities to which free individuals in the social community were subject. This is expressed in particular in the social value component “honor”, which formally possessed in Kano every free individual who was not guilty of something particularly despicable. The existence of a term like “honor” also presupposes that there must be something like “ shame ”. A shame always arises from the violation of a generally applicable, social norm. It is less important whether this standard is codified as a law or whether this standard is “good custom”. Since a slave had no official honor with the Hausa , Fulani and others, there was nothing a slave should (or could) be ashamed of. The general view was that where there is no honor, there is no shame. While a free Muslim woman, for example, had to be ashamed of leaving the house without her body being completely covered, the public, lightly clad appearance for slaves was perfectly legitimate, "because she need not be ashamed of it." The same goes for B. for field work, for which a Muslim "woman of honor" should have been ashamed in the past. In this regard, the royal slaves in Kano, even if they had no other social rights, sometimes had more freedom than the free "citizens of honor", provided their rulers allowed it. However, the royal slaves in Kano were by no means lawless; in addition to their special loyalty to their king and master, they also had a certain code of conduct for their behavior in the community, which sometimes helped them to gain some recognition. Therefore, royal slaves were sometimes entrusted with particularly delicate and trustworthy tasks, such as: B. in difficult diplomatic negotiations outside the country.

Slaves were generally outside the jurisdiction, they could not be punished by third parties. In the event of a crime, their respective masters were held responsible. Royal slaves had special freedoms, provided that their behavior was approved by the emir, for in most cases it was impossible to prosecute the emir for anything. This was sometimes used by the emirs to commit acts that would normally have meant a serious breach of social norms for them. For example, royal slaves were sent to the forcible capture of particularly beautiful young women for the emir's harem. If these were free women, marriage to the emir was planned. In the event of a complaint from the woman's family, at best the slave who had committed the act was executed, even though he had actually only obeyed the orders of his master. Most of the concubines in the harems were the sisters, aunts, and daughters of the royal slaves.

In the past, an Islamic society combined very high moral and ethical standards with the office of ruler, which were also underpinned by religion. Unrestricted violence, such as that developed by the European aristocracy in modern times, was not possible in Islamic societies or would not have been able to survive in the long term.

“Although the negroes have no qualms about robbing their slaves of their lives, I have never had the opportunity to find out that they are torturing him or that they are exhausting him. The negro does not regard it as a great evil to be a slave in the country itself; but to be led out of the country or killed is one thing to him. "

literature

- Brodie Cruickshank, An eighteen-year stay on the gold coast of Africa , Leipzig 1855

- HC Monrad, painting of the coast of Guinea and the inhabitants of it as well as the Danish colonies on this coast, designed during my stay in Africa from 1805 to 1809 , Weimar 1824

- Wilhelm Bosmann, Reyse to Guinea or detailed description of the gold pits / elephant teeth and slave trade / along with their inhabitants customs / religion / regiment / wars / heyraths and burials / also all animals located here / so previously unknown in Europe , Hamburg 1708

- Sean Stilwell: Power, Honor and Shame: The ideology of Royal slavery in the Sokoto caliphate. Africa, 70 (3) (2000) 394-421

specifically on the subject of morality and ethics in relation to Islamic rulers see:

- Marc. Jos. Müller, About the supreme rulers under Muslim constitutional law , treatises of the philosophical-philological class of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences, 4 (3) (1847)

specifically on the subject of slavery and cohabitation see:

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Concubinage and the status of women slaves in early colonial Northern Nigeria , Journal of African History, 29 (1988) 245-266;

- ders., Concubinage in the Sokoto Caliphate (1804-1903) , Slavery and Abolition 11 (1990), 159-189.

Web links

- Mirjam de Bruijn, Lotte Pelekmans: Facing dilemmas: former Fulbe slaves in modern Mali. Canadian journal of African studies 39 (1), 2005, pp. 69-96