Taylor rule

The Taylor rule is a monetary policy rule for setting the base rate by a central bank . It was named after its inventor, the US economist John B. Taylor .

Taylor tried to find out how the US central bank, the Federal Reserve System (Fed) , sets the target value for its most important monetary policy instrument, the short-term interest rate ( Federal Funds Rate ) on the money market . In contrast to the European Central Bank, in addition to the goal of stable prices, the American Central Bank also strives for high employment and moderate long-term interest rates. In 1993 John B. Taylor developed this formula in order to precisely quantify the Fed's reaction to changes in real economic development and inflation and thus to derive a target-oriented interest rate. It represents an empirical approach based on economic research. Basically, the studies refer to the G8 countries and their success in achieving their monetary policy goals. For this reason, the rule can be adapted to many other countries. The Taylor rule is intended to be a kind of guide for central banks.

Taylor's intention

It was originally Taylor's intention to find a rule that was suitable to trace the interest rate policy of the Fed (Federal Reserve System). Thus his aim was to devise an alternative to setting the short-term interest rate of monetary policy. He attached great importance to their simplicity and robustness. It should serve as a means of adequately recording and evaluating the central bank's monetary policy. But at the same time it should be a concept as a guideline for policy decisions by central banks. From a legal situation in the USA (the Fed must take price level and economic developments into account) arose its premise that the central banks determine their interest rate policy depending on the current inflation rate and the economic situation.

Components of the Taylor formula and their interpretation

- expected inflation rate

- real equilibrium interest rate

- "Inflation gap" Difference between expected inflation (measured by the GDP deflator) and inflation target (the one that the central bank is aiming for in the medium term)

- "Output gap" is the logarithmic difference between the actual real GDP and the production potential (defined as production volume according to the long-term growth rate)

The expected inflation rate and the real equilibrium interest rate provide, based on the Fischer equation , a benchmark for the short-term interest rate, the level of which is compatible with the achievement of the inflation target at full load ( ). Price stability and economic growth or economic stabilization are summarized in the output and inflation gap. If the inflation target is exceeded in the inflation gap, this requires an increase in the short-term interest rate above the benchmark and vice versa. The output gap captures economic aspects and price perspectives. It is advisable to lower the short-term interest rate when capacities are not fully utilized ( ) and increase when capacities are fully utilized ( ). Both indicate how strongly the central bank assesses deviations from potential output and deviations from the target inflation rate in monetary policy terms. and indicate how strongly monetary policy should react to changes in the inflation rate from its target or production from the level of production. According to Taylor, this is set at an amount of . Thus, if there is any sign of inflationary pressure, the central bank can raise real interest rates in order to restore equilibrium. The use of expected inflation on the right-hand side of this equation shows that although the nominal short-term interest rate acts as a monetary policy instrument, it is ultimately about influencing the real interest rate.

The Taylor rule as a further development of the IS-LM model

In the Taylor rule, classic monetarist-Keynesian elements and elements of the “new classical macroeconomics” are linked. It uses the interest rate depending on the target deviations for macro variables that are considered relevant for monetary policy. This makes the LM condition superfluous in the IS-LM model because it is used to recursively determine the nominal money supply. In the new version of the IS-LM model, the coordinates measure the real interest rate (y-axis) and the real output (x-axis). The IS line is based on the usual hypotheses. Overall demand continues to react in the opposite direction to real interest rates. As a result, the position of the line is determined by the demand component and the supply of goods at all times follows the demand. The position of the new MP line (MP = monetary policy) depends on the current inflation rate and the monetary policy target rate. With regard to the Taylor rule, the central bank follows a simple variant. If the inflation rate is above the monetary policy target, it increases the real interest rate (and vice versa). The bank knows the expected inflation rate (by assuming rational expectations) and controls this through the nominal interest rate in order to influence the real interest rate. However, it is based exclusively on the current inflation rate. The figure shows that there is always a clear and opposing relationship between output level and inflation rate.

Process steps for deriving an appropriate rule

In order to influence deviations from the price and output targets, the short-term interest rate can be determined by deriving it from individual procedural steps. To do this, the monetary policy rule to be checked must be inserted into the selected model and resolved by choosing the possible solution algorithm. The next step is the analysis of the stochastic distribution of the variances of the individual variables (input, output, underemployment). Finally, the evaluation of the monetary policy rule with the fixed properties and the verification of the robustness of the model follow. This can be done through a comparison with other models.

Ways to use Taylor's rule

The Taylor rule is very changeable and can therefore be adapted to many different political circumstances. It can be seen as the basis for monetary policy decisions. Model calculations for the variation of the coefficients for the weighting of the expected inflation rate and the output gap are also possible.

Forms of Taylor's rule

The original Taylor rule

denotes the inflation rate and the inflation target, the difference between which results in the inflation gap. The output gap is indicated by y. The long-term development of GDP with normal utilization of the existing capacities can be described as production potential. The variables and again describe the equilibrium variables and the equilibrium real interest rate is described by.

Applied to the Fed, Taylor describes the following rule:

If the equation is adapted to the variables we have already used, it reads as follows:

The expectation that the past inflation rate will coincide with the future inflation rate is indicated with . The output gap ( ) is the deviation from the long-term growth path . The inflation gap is determined by calculating the deviation of the observed inflation rate of the past four quarters from the assumed target inflation rate of 2%. The level of the short-term interest rate is also based on the inflation gap (difference between current and target inflation rate). As described above, the coefficients ( and ) are also the policy-response parameters here.

From the formula it can be concluded that the more the output gap and the inflation gap deviate from the target value, the greater the scope of monetary policy in terms of interest rate policy. If the inflation rate and output gap match the target values, there is no deviation from the long-term growth path.

Assuming an output gap and an inflation gap of zero each, the nominal interest rate is the sum of the constant real interest rate and the targeted inflation rate. If you take a closer look at this equation, you can see that real interest rates rise above the equilibrium value when the inflation target is exceeded or capacities are overloaded. If there are signs of an exuberant economy, inflationary effects will result, with interest rates rising. However, if the economy is in a crisis, the inflation rate is expected to decline. By expressing the two weights α and β, the different target functions of the central banks can be made clear. Because the higher this is, the more deviations are included in the interest rate policy. Specifically, the Taylor rule implies that if the inflation rate increases by one percentage point, the federal funds rate increases by 1.5 percentage points. If GDP falls one percentage point below potential GDP, the federal funds rate must be reduced by 0.5 percentage points. In the event of inflationary pressure, this is intended to ensure that monetary policy becomes more restrictive in order to enable the real interest rate to rise. The Taylor rule can thus be understood in a positive and normative sense. In a positive sense, the rule provides an explanation for the development over time of a short-term controllable interest rate by the central bank. It can be understood as a rule for the reaction function in the normative sense.

A more general Taylor rule

(from the European Central Bank, Jarchow, Schinke und Schäfer)

The real equilibrium interest rate is described with r, the current inflation rate with and the target inflation rate with . The output gap (yy *) is equal to the previous rules. The policy-response parameters can be applied depending on the weighting of the inflation and growth components. This can be, for example, with a strong weighting for α 1.5 and for the output coefficient β 0.5. This weighting depends entirely on the priority given to the individual variables. In the present rule, the greater the inflation rate exceeds the target inflation value and the more the potential output is utilized (and vice versa), the greater the interest rate. It can be seen that the economy is in equilibrium when there is no deviation of GDP from potential output and the target inflation corresponds to the expected inflation. A difference to the original Taylor rule is that the target interest rate is not determined from current inflation and the equilibrium real interest rate, but from the target inflation and the equilibrium real interest rate. Another modification to the original rule is that the expected inflation is used instead of the actual inflation. The reason for this is the time lag that the effect of monetary policy on inflation is subject to.

Apply Taylor's rule to the euro area

(Applied through the analysis of the Bank for International Settlements (1999))

The equilibrium interest rate is assumed to be constant. The changed inflation rate compared to the previous year is . As before, further components of the formula are the output gap ( ), the target inflation rate ( ) and the current inflation rate ( ). A simplified form of the general, dynamic equilibrium model for representing the general economic situation as a function of shocks and temporal expectations can be represented in two equations.

The equation describes the supply side and thus the output. The goal is the current production decision . In the first bracket, the real interest rate is derived from the nominal interest rate ( ) minus the expected inflation rate for the coming period ( ). The expectations regarding future production conditions ( ) have a positive influence on the nominal interest rate. A stochastic disturbance term is taken into account with the variable . The parameters and are> 0. This equation shows the development of aggregate demand for a given political strategy.

The inflation rate results in what corresponds to the demand side. The current inflation rate results from price adjustments that are made based on expectations for the future inflation rate, and the current level of capacity utilization (roughly corresponds to the output gap and an interference term). Since only some of the companies make adjustments, the values of and are always between 0 and 1.

If one solves both equations by and on, we get: Short-term rates in the current period are called r * and the target inflation . The inflation gap ( ) relates to the deviation of the future expected inflation rate from the target inflation rate, which is weighted with α. Since the formula can lead to instability and arbitrary expectations, the ECB does not consider its use to be advisable. One reason for this can be the increase in the stability problem when the forecast period k increases. Given the sensitivity of monetary policy, it can cause extreme fluctuations in results. For this reason, the stabilizing properties of Taylor's rule are lost. But changes in expectations can also lead to economic developments. As a result, it is unclear to economic agents how the monetary policy system reacts to exogenous shocks. Ultimately, the anchor effect of the Taylor rule is lost, which leads the ECB to use it only as a guide for achieving monetary policy goals.

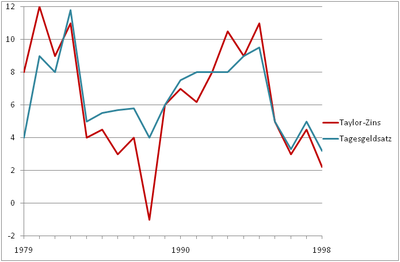

The Taylor interest rate in Germany

In Germany the inflation gap and output gap are weighted equally with 0.5 each and the inflation rate is based on the West German price index for life support. The inevitable inflation rate (or from 1985 the price norm) used as the basis for deriving the money supply targets from the Bundesbank serves as the inflation target. The output gap is based on the potential estimate by the West German Bundesbank. The equilibrium real short-term interest rate is set at 3.4%. This corresponds to the average of the real overnight money rate over the period under review from the 1st quarter 1979 to the 4th quarter 1998. If the Taylor rule is applied, it must be borne in mind when interpreting that other average values are also acceptable. The figure shows that the overnight interest rate observed is smoother than the calculated Taylor interest rate. If the Bundesbank had oriented itself towards the Taylor interest rate, this would have implied more interest rate movements ceteris paribus than it actually allowed with its concept. The reason for the strong fluctuations is that the Taylor interest rate does not take into account the negative consequences of an activist monetary policy. Despite everything, both interest rates have developed similarly. It is surprising that they are so similar, since the output gap played a major role in Bundesbank policy. This can be explained by the similarities between the Taylor rule and the money supply strategy. This means that if GDP grows more slowly than potential output, the central bank will make more money available through falling interest rates than would be required to finance ongoing growth.

A Taylor rule for the United Kingdom

(postulated by Nelson, 2000)

The equilibrium short-term interest rate for steady growth is marked with i * and the target inflation rate with . The inflation gap is weighted with a policy response barometer of 1.5. The output gap has a lower weighting of 0.5.

Taking into account the exchange rates

The inflation rate is shown here again by and the output gap by . The parameter et takes the place for the exchange rates. An increase means an appreciation of the domestic currency. The political influence is reflected in δ and ρ. A decreasing weighting of the past real exchange rates to one another corresponds to the relation of the two coefficients. This is caused by the effect of price rigidities in imports and exports on inflation rates. According to Taylor, it does not matter whether anticipated or current inflation rates are used, because they are often very similar and because anticipated inflation rates depend on the assumed transmission mechanisms. For small countries in particular, it makes sense to take exchange rates into account, because the coefficients and depend on the exchange rate reactions of political measures.

reception

Transmission mechanisms

- The financial market perspective assumes that the monetary policy measures will have an effect on returns. The intensity of the transmission effects via foreign trade depends on the sensitivity of the exchange rates.

- The credit channel, the effect of which is to increase or decrease the cost of credit. This can lead to small variances in inflation and output.

- A delayed price and wage adjustment, because inflation expectations can influence future price and wage adjustments.

theses

Fully or tend to apply:

- the smaller the inflation gap (or lower inflation rate), the greater the liquidity supply from the ECB

- the smaller the output gap (or the lower economic growth), the greater the liquidity injection from the ECB

- Price adjustments react to growth with an economic lag

- Wage developments react to economic growth with a delay

- Short-term interest rates respond to the expected deviations between the inflation rate and the target inflation rate

- Taylor's rule is suitable for assessing the monetary policy environment

Does not apply:

- Taylor's rule can be used as a rule-based form of monetary policy

- does not apply to the euro currency system because shocks require discrete interest rate control

- Applying the expected inflation rates gives better results than the current inflation rates

- according to Taylor, it does not matter whether the expected or current inflation rate is used

- Considering exchange rates can lead to better or worse results

- causes slightly worse results in the euro currency area d. H. greater variance in interest rates

Strengths and weaknesses of the Taylor rule

Strengthen

One advantage of Taylor's rule is its relative simplicity. It offers a comparatively clear structure of monetary policy arguments.

Furthermore, it offers many degrees of freedom in the choice of price variables and is therefore flexible.

In addition to the price level stability, Taylor also includes the economic development in the formula. He continues to assume that the central bank only controls the short-term interest rate and thus the money supply is endogenous.

It is also positive that it is relatively easy to apply by the central bank and that its application is relatively easy to understand for experts in monetary policy in the private sector. This makes it easier to communicate about monetary policy orientation.

Supporters of the forecast-based version even go so far as to claim that it contains all the relevant information for monetary policy decisions.

weaknesses

One of the biggest problems is the assumption of a constant real interest rate. Taylor used the long-term growth rate (GDP) of the US economy in place of the real interest rate. Although the two are interdependent, they cannot be equated. The rate of GDP growth is not an interest rate. So it cannot be ruled out that the central bank would have created a different growth rate with a different monetary policy. As a result, the central bank's interest rate policy would have produced a different equilibrium interest rate. The interest rate is a result of monetary policy decisions and is therefore not a variable derived from the real economy. With this fact, the Taylor rule loses its anchor of determining the interest rate and thus also its tax function as a guide.

The determination of the coefficients with which the output and inflation gap are weighted is also controversial. If a central bank attaches importance to a strict fight against inflation, it will value the inflation gap higher than the output gap. Determining an appropriate weighting cannot be correctly determined because it depends on several factors, such as B. the "inflation culture" or the labor market constellation. As a result, these quantities must be estimated, which can be very risky. It would also be possible, for example, that the weighting would have to be determined by politicians. It is also uncertain whether the inflation gap should be determined on the basis of the GDP deflator or on the basis of the cost of living index. Determining the size of the output gap is also not without problems. It always depends on which method is used for the calculation. The result will always be different whether you use the log-linear trend, the Hodrick-Prescott trend, or the estimate of a production function. These will be reflected directly in the level and in the course of the Taylor interest rate.

Another negative aspect is that the application of the Taylor rule could cause a somewhat higher economic volatility than the prevailing practice due to comparatively large fluctuations in the interest rate.

Another weakness is that, based on experience in many countries, the time lags of the interest rate signals are difficult to predict and the procyclical effect cannot be ruled out. A stock market crash, for example, also requires short-term monetary measures, but this does not necessarily mean that the central bank generally returns from a monetary policy linked to monetary policy to a discretionary monetary policy. Even in the case of a one-time price increase - such as B. as a result of an increase in VAT - there is a need for action in principle. The nominal interest rate used also leads to frequent criticism, as it cannot be negative. If it falls to a low level, the Taylor rule no longer succeeds in ensuring that the system is linked to monetary policy objectives.

Furthermore, an assumption that the real interest rate is constant is critical. The factors to be taken into account are the (expected) rate of return on property, plant and equipment, the general propensity to save, the general assessment of the uncertainties in the economy and the degree of credibility of the central bank.

One important point that is not taken into account is the need to be proactive.

literature

- Michael Woodford: The Taylor Rule and Optimal Monetary Policy. In: The American Economic Review. Vol. 91, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Hundred Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association , May 2001, pp. 232-237.

- Lars EO Svensson : What Is Wrong with Taylor Rules? Using Judgment in Monetary Policy through Targeting Rules. In: Journal of Economic Literature , Vol. 41 No. 2 (June 2003), pp. 426-477.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Heine, Hansjörg Herr: The European Central Bank. A critical introduction to the strategy and policies of the ECB. Marburg 2004, ISBN 3-89518-455-1 , p. 150.

- ^ John B. Taylor: An Historical Analysis of Monetary Policy Rules. (PDF; 1.5 MB) Working Paper 6768, Cambridge USA, October 1998, pp. 51–52. Retrieved November 25, 2010

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg: Fundamentals of monetary theory and monetary policy. Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-58148-5 , p. 313.

- ↑ Klaus Schaper (2001), p. 138.

- ↑ Johannes Treu: The Taylor interest rate and European monetary policy 1999–2009. ( Memento of the original from January 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 234 kB) Moritz Arndt University Greifswald, Faculty of Law and Political Science 2010, ISSN 1437-6989 , pp. 2–3. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), p. 313.

- ↑ Michael Heine, Hansjörg Herr (2004), p. 150.

- ^ Christian Peukert: The Taylor rule. (PDF; 175 kB) Exercise on empirical economic research, Ulm 2010, pp. 2–3. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ↑ Michael Heine, Hansjörg Herr (2004), pp. 150, 151.

- ^ Egon Görgens, Franz Seitz, Karlheinz Ruckriegel: European monetary policy. Theory, Empire, Practice. 4th revised edition. Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8252-8285-6 , pp. 228-229.

- ↑ European Central Bank. ( Memento of the original from February 26, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) October 2001 monthly report, p. 46. Accessed November 29, 2010

- ^ Franco Reither: Fundamentals of the New Keynesian Macroeconomics. (PDF) Hamburg 2003, pp. 2–3. Retrieved November 27, 2010

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), pp. 322–323.

- ↑ a b Ralph Anderegg (2007), p. 322.

- ↑ Johannes Treu: The Taylor interest rate and European monetary policy 1999–2009. ( Memento of the original from January 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 234 kB) Moritz Arndt University Greifswald, Faculty of Law and Political Science, 2010, ISSN 1437-6989 , p. 3. Accessed on November 16, 2010.

- ^ John B. Taylor: Discretion versus policy rules in practice. (PDF; 1.8 MB) In: Carnegie-Rochester Conferences Series on Public Policy. 39, 1993, p. 202. Retrieved November 27, 2010

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), p. 316.

- ↑ Egon Görgens, Franz Seitz, Karlheinz Ruckriegel (2004), p. 245.

- ↑ Michael Heine, Hansjörg Herr (2004), p. 151

- ↑ Johannes Treu: The Taylor interest rate and European monetary policy 1999–2009. ( Memento of the original from January 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 234 kB) Moritz Arndt University Greifswald, Faculty of Law and Political Science 2010, ISSN 1437-6989 , pp. 3–5. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), pp. 316, 317

- ↑ Johannes Treu: The Taylor interest rate and European monetary policy 1999–2009. ( Memento of the original from January 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 234 kB) Moritz Arndt University Greifswald, Faculty of Law and Political Science 2010, ISSN 1437-6989 , pp. 7–9. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), pp. 217-319

- ↑ Taylor Interest Rate and Monetary Conditions Index. ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . (PDF) Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report April 1999, pp. 51–52. Retrieved November 28, 2010

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), p. 317

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), pp. 319, 320.

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), p. 324f.

- ↑ Peter Bofinger, Julian Reischle, Andrea Schächter: Monetary Policy. Goals, Institutions, Strategies, and Instruments. New York 2001, ISBN 0-19-924057-4 , p. 274.

- ↑ a b c d Taylor Interest Rate and Monetary Conditions Index. ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Deutsche Bundesbank , Monthly Report April 1999, p. 50. Retrieved on November 28, 2010

- ↑ Michael Heine, Hansjörg Herr (2004), p. 153.

- ↑ European Central Bank. ( Memento of the original from February 26, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) October 2001 monthly report, p. 47. Accessed November 29, 2010

- ↑ a b Michael Heine, Hansjörg Herr (2004), pp. 153–155.

- ^ Klaus Schaper: Macroeconomics. A textbook for social scientists. Frankfurt / Main 2001, ISBN 3-593-36733-5 , p. 139.

- ↑ Ralph Anderegg (2007), p. 325.

- ↑ European Central Bank. ( Memento of the original from February 26, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) October 2001 monthly report, p. 49. Retrieved November 29, 2010

![i_t = r ^ {eq} + \ pi_t + 0.5 [y_t + (\ pi ^ * - \ pi ^ {ob})]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/32e326af5bba0882f0d550af50543aa321c13341)