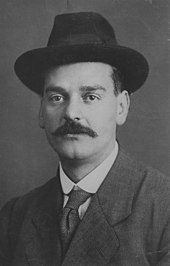

Gottlieb Duttweiler

Gottlieb Duttweiler (born August 15, 1888 in Zurich ; † June 8, 1962 there ; often called "Dutti") was a Swiss entrepreneur , politician , journalist and publicist . He is best known as the founder of the Migros company , which developed into the market leader in Swiss retailing under his leadership . He also founded the State Ring of Independents (LdU), a political party at the center of the political spectrum.

From 1925, Duttweiler changed the Swiss retail trade, which was heavily influenced by cartels , with Migros - first with the sale of groceries from moving vans , then also with shops . His rapid success, which he achieved with significantly lower costs and prices, aroused fierce resistance from established retailers, consumer cooperatives , associations and branded goods manufacturers . There were delivery boycotts and numerous legal proceedings which, however, helped Duttweiler and Migros to become more and more popular. With imitation products , he laid the foundation for the production of own brands . Repeated official harassment (up to a twelve-year ban on opening new branches ) drove him into politics. His “List of Independents” won seven seats in the National Council straight away in 1935 ; a year later he converted this loose group into a party. Duttweiler temporarily withdrew from politics in 1940 and sat again in the National Council from 1943 to 1949. He was then a member of the Council of States , and from 1951 until his death he was again a member of the National Council. He was also a member of the Zurich Cantonal Council from 1943 to 1951 .

In addition to his entrepreneurial and political activities, Duttweiler developed a lively journalistic activity. First, he wrote leaflets that advertised Migros and its goals in the service of consumers - in particular, the cheaper food and the promotion of public health . From 1927 onwards, hundreds of text advertisements were added, which appeared as a newspaper in the newspaper in several third-party publications. In 1935 he founded the weekly newspaper Die Tat (published as a daily newspaper from 1939), and in 1942 the weekly newspaper Wir Brückenbauer . In 1941, Duttweiler converted Migros from a stock corporation into several regional cooperatives , which are linked to one another via the Migros Cooperative Association. Giving away a prosperous company to its customers by issuing share certificates is a unique process in Swiss economic history. Duttweiler had a strong sense of mission and, under the catchphrase “social capital”, strived for a free market economy that is aware of its social responsibility. With the Migros Culture Percentage created in 1957 , he ensured that one percent of Migros' annual turnover is used for cultural and social purposes. In 1962 he founded the Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute , the first think tank in Switzerland.

biography

Childhood and youth

Gottlieb Duttweiler was born on August 15, 1888 in the house at Strehlgasse 13 in Zurich's old town , the third of five children of the father of the same name (1850-1906) and of Elisabeth Duttweiler (née Gehrig, 1857-1936). He was the only son and had four sisters. On the paternal side, the Protestant family had lived in Oberweningen in the Zurich Unterland from around 1500 ; In 1901 she was naturalized in the city of Zurich . On the mother's side, the ancestors can be traced back to the middle of the 18th century in Ammerswil in Aargau . The father had initially worked as an innkeeper and since 1886 he was the administrator of the Zurich Food Association (LVZ). Under his leadership, the LVZ joined the Association of Swiss Consumers (VSK), the predecessor of Coop , in 1890 and developed into the second largest consumer cooperative in Switzerland. Duttweiler senior occasionally took his son on horse-drawn carriage rides to the countryside, where he bought fruit and vegetables directly from the farmers.

In 1896 the Duttweilers moved into an apartment in the LVZ administration building, which was located in the proletarian district of Aussersihl . As the only one from a "better" family, Gottlieb junior always remained an outsider in primary school among all the working class children and was often involved in fights because of the bullying of his classmates. This did not change when he transferred to secondary school in the neighboring industrial district . His school grades ranged from “unsatisfactory” to “very good”. Towards the end of compulsory schooling, he discovered his commercial talent: he earned money raising rabbits, guinea pigs and white mice as well as taking portrait photography. It was more fun for him to earn the money than to own it, since for him it was at best a means to an end in order to be able to earn and spend even more.

In 1903 Duttweiler joined the commercial department of the Cantonal School in Zurich . He repeatedly came into conflict with the teachers, who described his behavior as "inattentive", "restless" and "improper". Finally the school management asked his father to take the son out of school. In 1905, Duttweiler began a commercial apprenticeship instead at the well-known Zurich grocer Pfister & Sigg , in addition to attending the commercial school of the commercial association . He was particularly fascinated by the buying and selling of goods, while the accounting did not appeal to him. His father died on June 10, 1906 after a long illness, whereupon he took his education much more seriously than before out of a sense of responsibility towards his mother and sisters. The family had to move out of the LVZ apartment and moved to the suburb of Rüschlikon . In April 1907 Duttweiler passed the final exam of the commercial school as the second best of 150 graduates of his class. In the same year he was declared unfit for military service due to the long-term effects of pleurisy he contracted at the age of eleven.

From businessman to partner

By the end of the practical part of the apprenticeship in spring 1908, Duttweiler took additional courses in commercial geography and learned Spanish . His teacher Heinrich Pfister sent him to Le Havre for six months to gain experience in international trade. There he also developed a telegraphic code with which orders for important commercial goods could be placed in a single word. The code was a great relief, which is why he was able to sell it to various companies and thus achieved considerable extra income. Duttweiler was daring, willing to take risks and communicative; it was easy for him to establish new business relationships. After a few months he was promoted to junior partner and began doing business in the food wholesale trade in several European countries .

Duttweiler recognized how much the middlemen made the goods more expensive. In order to reduce the costs for end consumers, he contacted exporters in Santos , who from then on supplied Brazilian coffee directly to Pfister & Sigg . After a few years he maintained relationships with almost 150 companies in Germany and abroad. Whenever he was in Switzerland, he took the train every day from Rüschlikon to Zurich to work. In 1911, on one of these trips, he met Adele Bertschi from Horgen , who was four years his junior and who was employed by the ETH Zurich seed control center at the time. For a long time she was dismissive of his advances, but Duttweiler persistently wooed her favor. Two years later they married on March 29, 1913 in the Reformed Church in Horgen , the marriage remained childless.

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War , Duttweiler took over the management of the Genoa branch in September 1914 and bought as much groceries as possible as prices rose rapidly. The wholesale trade experienced a boom of unimaginable proportions and neutral Switzerland developed into an important hub in trade between the warring countries, but was also dependent on imports itself. Duttweiler also bought goods unofficially on behalf of the Swiss Higher War Commissioner; These businesses alone were valued at CHF 50 million a year. Numerous bureaucratic hurdles (especially after Italy entered the war ) gave Duttweiler the idea of bringing Swiss freight trains directly to the ships so that the goods could get to Switzerland without touching Italian soil. Although Pfister & Sigg did not increase the commission , unlike many competitors, the profit rose to more than 30 times the pre-war level. In its heyday, the company controlled a seventh of Swiss coffee imports and a third of trade in technical oils and fats.

Duttweiler felt unjustly rewarded and demanded a quarter of the profit, since the excellent business results were mainly due to him. While Heinrich Pfister wanted to meet the demand, Nathan Sigg, the other partner, was reluctant. To show how serious he was, Duttweiler resigned in April 1915 from the end of June. Pfister did not want to let his best employee go under any circumstances and prevailed, whereupon Duttweiler got a 23 percent stake. As an authorized signatory , he traveled almost non-stop between Switzerland, Italy, France and Spain in order to remove obstacles in the movement of goods. In September 1917 Sigg had had enough of the increasingly risky business and got out. Duttweiler took his place as a new partner and the company was now called Pfister & Duttweiler . In Rüschlikon he had a stately country house built with a bowling alley and a hall with columns (the architect was Hans Vogelsanger , the husband of Adele's sister). From Italy he had three railway cars full of art objects and antique furniture come to equip his house. But he was hardly ever to be found there, since he traveled to New York for a few weeks in September 1917 and for six months in March 1918 in order to establish new business relationships. Although he set up a branch there, he could not achieve anything concrete, since the United States only delivered to its allies.

Liquidation, Farmer in Brazil

At the end of the war, Pfister & Duttweiler was an international company with enormous stocks and its own edible oil factory in Málaga . It pursued ambitious expansion plans, but was surprised by the onset of hyperinflation in several European countries and the drop in food prices. Duttweiler tried to compensate for part of the losses by speculating à la baisse with currencies. Rudolf Peter, the chief accountant who was newly hired in the summer of 1920, quickly demonstrated that the bookkeeping had been carried out far too superficially and negligently. In fact, the company had a debt of CHF 12 million. In order to prevent unregulated bankruptcy , the banks agreed to carry out a silent liquidation and to continue the business until all creditors were paid off. Both partners contributed their considerable private assets to the liquidation estate, so that by the end of the proceedings on July 12, 1923, a total of CHF 11.6 million had been paid - significantly more than the agreed bankruptcy dividend of 60%. Duttweiler, who among other things had to part with his luxurious country house and the art treasures, made sure that all employees got a new job.

While the liquidation proceedings were still in progress, Duttweiler looked for new opportunities. In the late summer of 1921 he planned to start a new life as manager of an oil mill in Valencia , but then changed his mind. Financially, he reorganized himself with business for his own account, which he handled in Poland . In particular, the trade in Polish sugar , which he was able to sell in Hamburg at below world market prices, turned out to be extremely profitable. At the turn of the year 1922/23 he planned to mine coal and oil in Poland, but the founding of a company did not materialize. In July 1923 Duttweiler traveled to Brazil with his wife Adele . On the one hand, he wanted to collect an outstanding balance from a former partner company, on the other hand, he wanted to visit one of his sisters who had emigrated there (her husband ran a subsidiary of the Bally shoe company ). He liked the landscape in the state of São Paulo so much that he bought a fazenda without further ado in order to get to know the food trade from the producer side for at least a few years.

The manor had an area of 2400 hectares , of which only 200 were arable . With the help of farm workers, Duttweiler planted rice , corn , beans , cassava and sugar cane . They also planted 30,000 young coffee trees that would bear fruit after about five years. 300 head of cattle grazed in the pastures. The house had not been inhabited for two years and was in poor condition. Gottlieb clearly enjoyed life as a farmer, Adele, on the other hand, felt uncomfortable right from the start, fell ill and lost a lot of weight. In February 1924 the couple returned to Zurich. A doctor found that the hot, humid climate and unfamiliar diet had negatively impacted Adele's red blood cells; in the longer term there would have been a decomposition of the blood. Duttweiler instructed his brother-in-law to sell the fazenda. He judged his short time as a farmer to be a “physical and mental sweat cure”.

Foundation of Migros

Duttweiler concluded various deals in Germany and Poland. He also applied to the VSK for a position as a buyer and dispatcher, but was rejected. Meanwhile, he noticed the huge discrepancy between wholesale prices and those in stores and he decided to get to the bottom of the matter. At the beginning of 1925 he conducted intensive research at the statistical office of the city of Zurich by comparing the food prices of different countries and cities. He received support from his cousin Paul Meierhans who worked there and his superior Carl Brüschweiler . Together they found that Swiss food prices rose sharply within a few years and were now the highest in Europe. Reasons for this were the fragmentation of the retail trade into countless small businesses with low turnover, too expensive shop fittings and rents, spoilage of food due to long storage, high expenses due to discount systems and small purchase quantities, price regulations from branded goods manufacturers , time-consuming weighing and packaging of the smallest quantities, high advertising expenditure as well as leaving a cover letter . Also presented Duttweiler increasing corporate - protectionist tendencies certain: The retailers were interest groups , purchasing groups organized and discount clubs to the chain stores and consumer cooperatives confront. On the other hand, the latter - much to his displeasure - neglected their original role as price regulators and offered their goods at the “local” prices of the retailers.

In Duttweiler's opinion, only the consistent application of the principles of Fordism and Taylorism were able to sustainably reduce costs for end consumers: large sales with a small profit margin, service to the consumer , his participation in the advantage of increasing sales through cheaper goods, classification of articles, small stocks and maximum utilization of working hours. The elimination of the middleman, the rationalization of sales and the abandonment of branded goods were essential for achieving these goals. His former chief accountant Rudolf Peter drew Duttweiler's attention to the mobile shops that were widespread in the USA at the time. There, comfortably furnished buses operated outpatient trade in rural areas and offered the goods they were carrying at a low surcharge. Duttweiler wanted to transfer the concept to Swiss conditions, but wanted to use trucks , since price reductions were his primary goal. It was through Meierhans that he met the national economist Elsa Gasser , then a business journalist for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung , with whom he discussed the idea. It encouraged him in his plan, and at the same time it was the beginning of decades of collaboration. Duttweiler promised his wife Adele: "If this enterprise doesn't succeed, I won't start anything new." As a result, she was his most important advisor and he discussed all strategic decisions with her before making a final decision.

Thanks to his good reputation, Rudolf Peter easily found investors, including the lawyer Hermann Walder . He then presided over the board of directors , while Duttweiler acted as managing director . Peter, in turn, initially took over accounting for half a day a week and rose over the years to become chief financial officer. Migros AG was founded on August 11, 1925 with share capital of 100,000 francs, and it was entered in the Zurich commercial register four days later. The new company chose a bridge symbol as its logo, as it saw itself as a link between producers and consumers. How the name Migros came about can no longer be determined exactly. The most common explanation relates to the targeted price positioning in the middle between en-wholesaling (wholesale) and en-détail (retailing), i.e. to a certain extent mi-wholesaling (medium -sized trade ). The name had the advantage of being applicable in all national languages. On August 25, five converted Ford TT trucks drove for the first time according to a fixed timetable on several routes in Zurich and offered six fast-moving items in simple packaging. The prices were up to 30% below the usual, the selling time at the stops was limited to 15 minutes.

Harassment and arguments

Grocers and associations tried to make the new competition, which had completely unexpectedly penetrated the cartelist retail trade, to disappear. Provocateurs harassed the waiting customers or denounced them to their employers, were violent towards the chauffeurs and sabotaged the sales vehicles . Numerous shops offered the items sold by Migros at below cost , but the rapidly growing clientele saw through the intention and remained loyal to the new provider. Association officials attacked Migros in polemical newspaper articles or commissioned defamatory letters to the editor. Social democrats and communists sensed a big capitalist conspiracy aimed at lowering wages by lowering food prices. The grocery association Zurich, once run by Duttweiler's father, regarded every purchase made by a member of the cooperative at Migros as a betrayal of the working class . Regardless of this, the vending trucks soon drove on routes outside the city.

From the beginning, the food manufacturers were also part of the opposition. Associations decided on delivery blocks and threatened their members with boycotts if they continued to supply Migros. Individual producers willing to deliver deposited their goods in secret warehouses at night, where the chauffeurs picked them up in the morning. Duttweiler responded by expanding the range and temporarily switching to imports. To reduce costs further, in January 1926 he saved the need for passengers and the chauffeurs had to deal with the sale on their own. So that you don't waste time counting change, he introduced another innovation: round prices for uneven amounts of weight. Although this was not at all in line with previous shopping habits, sales increased significantly. At the request of many customers who could not be at the stops at the specified times, Migros opened its first store in Zurich in December 1926 . This proved to be a great success despite the minimalist furnishings (Duttweiler did not want to invest more than 200 francs).

Duttweiler was prepared for the often-voiced accusation that outpatient grocery sales were unsanitary. As early as September 1925 he had commissioned Wilhelm von Gonzenbach , the director of the hygienic-bacteriological institute at ETH Zurich, to provide an expert opinion . It came to the conclusion that the sale of sealed food from trucks was harmless and even helped to improve public health , since large sections of the population were supplied with fresh goods. In 1928 Migros acquired the insolvent alcohol-free Weine AG in Meilen (today's Midor ), which coincidentally began the vertical integration of the previously pure trading company into industrial goods production. The first Migros production company was the first to significantly expand the production of sweet cider and cut the price to almost half, whereupon the competitors had to follow suit. The former niche product developed into a popular drink in a short time. Surprised by the success, Duttweiler consistently geared marketing towards life reform and social hygiene endeavors. Although he enjoyed drinking wine and smoking cigars privately, he deliberately avoided the lucrative alcohol and tobacco sales. In this way, Migros strengthened its own brands with significant advertising , moved away from the image of the pure discounter and positioned itself as a provider of inexpensive and healthy products of high quality.

Numerous self-made articles and several production facilities were added in the following years. Duttweiler mockingly thanked his opponents, «... who, through their resistance, spurred us on to higher performance and new ideas. We wouldn't have the entire production if we had been supplied. " In 1929, the collaboration with Haco , which continues to this day, began in 1929 , whose operations manager Gottlieb Lüscher followed Duttweiler's commitment to lower prices with sympathy. Migros was now able to offer imitation products of the same quality that competed with established branded products. Duttweiler created brand names and packaging that were closely based on the originals or parodied them. In particular, he wanted to force competitors to lower prices. For example, he praised Eimalzin as an alternative to Ovaltine , whereupon Wander AG launched an advertising battle that rocked each other to defame each other. In 1931, Migros ended the monopoly of the decaffeinated coffee Hag with Kaffee Zaun . In the same year, she challenged Henkel AG , the manufacturer of Persil , with the detergent Ohä : The package showed the words " Ohne Hänkel" and a kettle whose handles (or "handles") were crossed out. When Henkel threatened consequences, Duttweiler had a fig leaf printed on the packaging in such a way that only "Oh ... Huh ..." could be read.

Migros could not be slowed down with boycotts or disruptive actions. Since the outpatient trade was subject to the legal regulations for peddlers , the opposition exercised instead influence on canton and communal authorities and justified this with the alleged endangerment of the state-supporting middle class . Each canton set the amount of the wagon fees at its own discretion. While the vending vehicles were banned from the start in the canton of Aargau, the fees in the canton of Bern were so high that their use was soon no longer worthwhile. Many communities demanded additional bus stop fees or made harassing conditions. Duttweiler organized referendums against the tightening of the peddler laws passed by several cantonal parliaments , which were primarily aimed at Migros . He opposed most of the political parties and campaigned intensively. He succeeded in convincing the voters of the cantons of St. Gallen , Thurgau and Zurich in favor of Migros. In two other cantons, however, he suffered defeats: The canton of Schaffhausen doubled the fees, while the canton of Basel-Landschaft raised them so massively that Migros stopped selling cars there for several decades. From Dutweiler's point of view, only the authorities in the canton of Basel-Stadt treated his company fairly, as the fees there were comparatively low.

Litigation and failure in Berlin

Duttweiler involved the authorities in lengthy administrative proceedings because of the conditions that had been imposed on the sales vehicles . He disregarded their orders and consciously accepted criminal charges and fines . He then provoked the authorities into numerous media-effective court cases across several instances. The city of Bern caused him a great deal of inconvenience . On February 27, 1930, the city police confiscated three sales vehicles, which gave Migros free advertising for the branch opened the day before. When Duttweiler refused to pay a fine of 400 francs in another legal case in February 1931, a chest of drawers was seized on him . He felt this to be particularly unfair, as the judgment had only come about because of a calculation error by the Bern Higher Court and could not be appealed. In a leaflet that he had enclosed with coffee and flour parcels, he addressed the Bern customers directly and asked them to use the enclosed postal check form to deposit ten cents each in favor of Migros. A total of 4,800 payments were received, and he donated the excess of 80 francs to unemployment welfare.

Civil and criminal proceedings for name protection, trademark protection and unfair competition offered Duttweiler additional stages. By incessantly attacking his opponents in polemical newspaper articles, accusing them of exorbitant prices or bringing copycat products onto the market, he challenged them to sue . The provocations were carefully prepared and the result of lengthy discussions with his lawyer Hermann Walder. Duttweiler was not only a defendant, but presented himself as the protector of defenseless consumers who defended himself against overpowering associations and corporations. The negotiations were public, which is why the press reported regularly about Duttweiler and Migros products; the advertising value of the coverage ran into the millions. The courts mostly found that Migros had made a significant contribution to a general reduction in the price level, which should be emphasized in view of the economic situation. They condemned Duttweiler and Migros to small fines, to a moderation of the tone in the advertising or to small changes. Overall, the Migros litigation cost little, but brought it a lot of publicity, while Duttweiler rose to become a well-known figure in public life throughout Switzerland. Years later he said that in its early days, Migros had too little money to advertise across the board. He therefore took into account the predictability of the opponents: "We have always succeeded in meeting our needs for opponents who make us known." Do little he could contrast with trials of the politically protected virtual monopoly of Unilever on edible fats and oils . For this reason, Migros was so severely disadvantaged in the allocation of raw material import quotas that it had to temporarily interrupt its own production in 1935.

In 1930 the Finow Farm in Eberswalde approached Duttweiler and asked him for advice on setting up a Migros-like sales system in Berlin . When the company got into trouble, it was taken over by him as a private person (Migros itself was not involved) and by partners from Geneva and the Netherlands in January 1932 . The resulting Migros-Vertriebs-GmbH served more than 2000 stops with 76 vans from June 10, 1932. While the press reported benevolently, the crisis-ridden Berlin retail trade reacted indignantly to the foreign competition, but could do little. This changed with the seizure of the Nazi Party in January 1933, when Adolf Hitler promised the middle class against " Jews and plutocrats to protect." As a result, the authorities covered the company with bureaucratic harassment and members of the National Socialist Combat League for small and medium- sized businesses threatened the customers. In order to avoid the Jewish boycotts imposed in April , Duttweiler and his senior employee Emil Rentsch presented evidence of Aryans issued in Switzerland . Although the NSDAP removed the company from the boycott list, the Kampfbund intensified its attacks. In view of the hopeless situation, the shareholders decided in autumn 1933 to cease business activities and liquidate, which dragged on until 1937.

The branch ban and its consequences

Since the beginning of the global economic crisis , Swiss economic policy has been increasingly shaped by dirigistic measures to protect various industries . On October 14, 1933, at the request of Parliament , the Federal Council passed a federal resolution on the “prohibition of opening and expanding department stores, department stores, uniform price stores and branch stores”. From November 10, 1933, the ban on branches also applied to the business of large companies in the food retail trade. The federal decree was not explicitly directed against Migros, as it also affected consumer cooperatives and other chain stores, but Migros, as an ambitious and expanding company, was particularly affected. Duttweiler had underestimated the scope of the branch ban at the beginning because he had been distracted by the events in Berlin and the food trade was restricted only afterwards. The federal resolution, limited to two years, had been declared urgent, which is why no optional referendum could be called against it. In the fight against the law, which renowned constitutional lawyers like Fritz Fleiner and Zaccaria Giacometti described as unconstitutional, Duttweiler wrote numerous newspaper articles. He also gave widely acclaimed lectures and organized a petition in twelve cantons, which brought in 230,000 signatures. Nevertheless, the branch ban was extended several times and was in force for a total of twelve years. During this time, Migros was limited to 98 branches, only three more were added due to cantonal exemption regulations.

Meanwhile, Duttweiler tried to contribute to solving the retail trade crisis. In September 1933, he proposed measures to improve quality and provide financial support for grocery stores in need. While the Federal Office for Industry, Commerce and Labor (Biga) signaled interest, the associations and organizations invited to a conference categorically refused to negotiate with him. In October 1934 another conference took place, but it remained fruitless. A month later, Duttweiler submitted his proposals to the Swiss Trade Association (SGV). Again there was no rapprochement and in May 1935 the SGV declared that it was pointless to continue negotiating with him; the Biga should also refrain from further involving him as an expert. As a result of this blockade, Duttweiler launched the “Giro-Dienst” in 1937: independent grocery stores took over the Migros sales system and were able to purchase Migros products at more favorable terms, but remained free in terms of product range and purchasing. Dozens of stores joined this affiliate program. Several cantons considered the Giro service to be a circumvention of the branch ban, while the Department of Economic Affairs found that Giro stores were not Migros branches.

In 1932 Duttweiler also began to influence agricultural policy. In response to increasing protectionism , he and the agronomist Heinrich Schnyder developed an action program that was supposed to guarantee farmers a higher income without having to increase import tariffs. Since the Swiss Farmers' Association and other agricultural associations refused to work with him, Duttweiler decided to no longer pay attention to the numerous questioners and to simply act. For example, Migros bought the products from farmers at a higher price than the competition (and still remained the cheapest supplier). Around the turn of the year 1934/35, she sold boiled butter at cost price, triggering a sales surge that made the Swiss butter mountain disappear in a short time - a problem that had previously been discussed at several conferences without any results for years. When the Swiss franc was devalued by 30% in September 1936, Duttweiler announced on leaflets that Migros would not increase its prices. In the case of imported goods, he consciously accepted losses until the government lowered the customs tariffs a few weeks later. In 1942, together with the Free Association of Swiss Cheese Traders , after seven years of service, he succeeded in lifting the monopoly-like trading privileges of the Swiss Cheese Union .

In March 1935, Duttweiler visit received by a German travel professional who suggested him with vacation packages to tourism in Switzerland to revive. This was in an existential crisis due to a sharp drop in the number of guests and excessive prices. Duttweiler quickly decided to put the idea into practice and in the following month founded the Hotelplan cooperative , in which Migros and tourism companies were involved. For the first time ever, people from simple backgrounds should be able to afford a holiday with inexpensive all-inclusive offers. In contrast to the totalitarian mass organizations Dopolavoro and Kraft durch Freude (which Duttweiler loathed), vacationers should be able to organize their leisure time individually within a certain region. In a few weeks Emil Rentsch built up an organization and in June the first special trains from Germany and abroad started to travel to Lugano ; further destinations were added in quick succession. By 1939, over 800 hotels, railway companies and shipping companies had participated in the hotel plan. During the Second World War it was temporarily reduced to a small travel agency for domestic travel. Duttweiler did not lay off the employees, but instead used them for some wartime economic functions such as Migros' rationing system .

Entry into politics

With petitions, referendums, newspaper articles and lectures, Duttweiler has been influencing politics for years. For a long time, however, he was reluctant to seek political office before allowing his closest friends to change his mind. He later said that he "got into politics". He explained his hesitation as follows: “You can't ask anyone to share the political views of their macaroni supplier. The risk is very great that you will lose customers as a result. I can hardly believe that you win customers through politics. " In view of its failure during the global economic crisis, Duttweiler considered a renewal of politics to be entirely desirable, but he regarded the anti-democratic front movement as incompatible with the liberal Swiss fundamental values. Instead, he wanted to offer protest voters an alternative that was not located at the extremes of the political spectrum, defended the interests of consumers and fought the power of interest groups and cartels in parliament. On the other hand, he did not want a well-organized party, but contented himself with a simple electoral list.

On September 17, 1935, Duttweiler announced that the «Group of Independents» would participate in the upcoming National Council elections in 1935 . During the election campaign, he campaigned for voters at numerous events. He was not a brilliant speaker, but he had the ability to make complicated economic matters easily understandable. His speeches seemed chaotic at times, but were always peppered with humorous punchlines. He spoke in a casual, conversational tone and responded to heckling with ironic remarks. The election result on October 27th was a sensation: the Independents won seven seats in the National Council , five of them in the canton of Zurich , where they were the second strongest party behind the Social Democrats with 18.3% of the vote . Duttweiler himself managed the election at the same time in the cantons of Zurich, Bern and St. Gallen, whereupon he accepted the Bern mandate. The bourgeois press ridiculed the independents as "Duttweiler's million in the Federal Palace - a one and six zeros after it". In order to prevent that a politician could ever again celebrate such a great personal electoral success, the parliament decided before the elections in 1939 to ban simultaneous National Council candidacies in more than one canton (this regulation still applies today).

After a year, Duttweiler saw that the new movement, contrary to its previous intention, needed organizational structures if it wanted to achieve its goals. Together with like-minded people, on December 30, 1936, he converted the group of independents into a political party , which was given the name Landing Ring of Independents (LdU) and was open to anyone who professed democracy. The delegates elected him in January 1937 as party chairman ("regional chairman"). He held this office until 1951, with the exception of the years 1948/49. In parliament it was difficult for the LdU to find a clear line, especially since Duttweiler dominated the parliamentary group and the other members next to him were hardly noticed. Hostile from left and right, he rarely got one of his motions through. He did not allow himself to be squeezed into a rigid ideological scheme and occasionally changed his mind when it seemed appropriate to him; he was either a “Communist friend” or a “Nazi”. In 1936, Duttweiler was the only member of the National Council, along with the frontist leader Robert Tobler , to speak out in favor of the popular initiative that called for a Masonic ban - in order to set an example against the "unity of opinion". On the other hand, he advocated job creation measures demanded by the Social Democrats.

On June 25, 1940, three days after France's surrender , Federal President Marcel Pilet-Golaz gave a radio address which, with its ambiguous remarks about an authoritarian renewal of democracy , could be understood as an adaptation to the Nazi state . As a member of the power of attorney commission of the National Council, Duttweiler was very critical. He firmly believed that the government must take a firm and determined stance and not give in on even small things. He then gave a series of lectures with which he intended to strengthen the will to resist. Its motto was “Our Struggle” - quite deliberately as an antithesis to Hitler's Mein Kampf . Duttweiler called on the total of 25,000 listeners to make every effort for effective national defense in order to protect freedom and democratic ideals. For a while he was a member of the Gotthard League , which also wanted to strengthen the resistance, but did not accept Jews or Freemasons.

The controversy surrounding the Federal President reached a climax when he received the leaders of the Swiss National Movement for a personal audience on September 10, 1940 . Four days later, Duttweiler learned from Hans Hausamann , a member of the Officers' Union resistance group , that Pilet-Golaz had ordered the release of 17 German air force pilots who had been forced to land and the transfer of their planes for no consideration . On September 17, Duttweiler wrote a confidential letter to the National Councils and the Council of States, asking them to ask Pilet-Golaz to resign immediately. Only the LdU and the Social Democrats accepted this request, while the other parties contented themselves with a reprimand. The letter leaked to the press and Ludwig Friedrich Meyer , parliamentary group leader of the FDP , accused Duttweiler, without evidence, of having committed an indiscretion. The governing parties and the media put his "word break" in the foreground, while he himself was not allowed to inform the public comprehensively because of the censorship regulations . On December 10, the National Council decided with 59 to 52 votes to expel Duttweiler from the Power of Attorney Commission. He immediately resigned as a national councilor, while the LdU parliamentary group stayed away from all meetings in protest until the end of the year.

Economic and intellectual national defense

Due to his negative experiences in Berlin, Duttweiler was convinced early on that the National Socialists wanted a war. In August 1934, he applied to the military department that importers, in the interests of national economic defense, should stock up on long-lasting foodstuffs in order to avoid bottlenecks like those during the First World War. His request went unanswered. In February 1938, he went public in newspaper articles and made recommendations on household supplies. He provided tin cans for storing food and gave advice on stock keeping . His competitors expressed the accusation that he was less concerned with the common good than with increasing his own sales. The food retailers' association newspaper even described him as a panic maker who endangers peace and security. Widespread hamster purchases during the Sudeten crisis in September 1938 confirmed Duttweiler's conviction. When Hitler continued his policy of aggression after the Munich Agreement , the Federal Council finally felt compelled in February 1939 to ask the population to stock up on supplies.

In the summer of 1938, Duttweiler had the idea of storing food in underwater tanks and sinking them into Swiss lakes. He wrote in a newspaper article that storage costs next to nothing compared to above-ground warehouses, the constant low water temperature of around 6 ° C makes artificial cooling superfluous and the tanks are safe from air attacks . There was an intensive correspondence with Federal Councilor Hermann Obrecht , which initially remained unsuccessful due to differences of opinion. In the meantime, Duttweiler commissioned the head of the Migros laboratory with the necessary calculations and experiments. In April 1939, together with other entrepreneurs, he founded the not-for-profit “Cooperative for the Procurement and Storage of Raw Materials and Food” (Gerona), which was awarded federal subsidies of 25,000 francs. At the end of July 1939, the Gerona sank a tank with 230 tons of grain near Därligen in Lake Thun . When she brought the “largest tin in the world” back ashore after four and a half months, the contents were perfectly preserved. However, due to official resistance, there were no further underwater storage on a large scale and the Gerona dissolved.

In October 1937, Duttweiler submitted a postulate to the National Council with the aim of purchasing 1,000 aircraft for the Swiss Air Force and training 3,000 pilots. In order to advance the training, he founded the In Memoriam Bider / Mittelholzer / Zimmermann cooperative in August 1938 . The project came to nothing, as the pilots trained by the cooperative were often not assigned to the air force for military service and large parts of the army command viewed the border fortifications as a significantly more important defense measure. After a year, the cooperative ceased operations. Shortly after the outbreak of World War II, Duttweiler suggested to the Federal War Transport Office (KTA) that a truck convoy should be formed to ensure that essential goods could be imported via southern France. The KTA saw no need, which is why in May 1940 he bought 50 trucks in the USA for his own account. Although General Henri Guisan supported the action, the Council of States unanimously refused to even discuss whether the federal government should assume the costs. Since the trucks could not be brought to Europe due to the lack of diplomatic protection, Duttweiler sold them to the United States Army for an unwanted profit of around 400,000 francs. A year later, the KTA was still forced to organize convoys at significantly higher costs.

In a letter to General Guisan in June 1940, Duttweiler complained about Switzerland's practice of continuing to allow coal transports between Germany and Italy . He suggested installing explosives in the Gotthard and Simplon Tunnels in order to have diplomatic leverage. In the event of a blast, the rubble should be mined so that coal transport to Italy would come to a standstill for a long time. The Swiss Federal Railways rejected the proposal because freight traffic should be maintained as a secure source of income. From May 1941, Migros participated in the development of Swiss ocean shipping . Together with business partners, she founded Maritime Suisse SA , which acquired two old freight steamers for transporting food. Duttweiler was a member of the board of directors of this shipping company . After two years, Marc Bloch, one of the partners, wanted to take over the majority of the shares. He apparently did this under pressure from the KTA, which wanted to damage Duttweiler politically (Bloch had close ties to the extreme left in Geneva). Under these circumstances, Migros considered it appropriate to sell its shares in September 1943 at a loss.

Duttweiler actively supported the Intellectual National Defense , an official political and cultural movement that wanted to protect values and customs perceived as “Swiss” in order to ward off totalitarian ideologies. At the end of 1939 he was the editor of the illustrated book Eine Volkes Sein und Schaffen , a commemorative work of the Swiss National Exhibition , which was sold at cost in an edition of 430,000 copies. In 1940 he was one of the founders of the Swiss sponsorship for mountain communities . In 1942 he organized a fundraising campaign for the children's aid of the Swiss Red Cross , which brought in two million francs. He also had a great influence on Swiss filmmaking . After Migros made a significant contribution to the increase in the share capital of the film production company Praesens-Film in 1943 , Duttweiler was a member of its board of directors. Praesens-Film produced feature films that were the only ones in the German-speaking world to revolt against totalitarianism. The film Marie-Louise , premiered in 1944, threatened to flop. However, Duttweiler was very touched and without further ado bought thousands of cinema tickets which he gave away to customers who were shopping outside of the rush hour. Marie-Louise was a commercial success and two years later became the first Swiss film ever to be awarded an Oscar .

Conversion of Migros into a cooperative

Increasingly, Duttweiler realized that he also had social responsibility with his commercial activities. For example, in 1943 he introduced a label called Vota at Migros , which marked offers that were made at a fair price, in good quality and under decent working conditions. Ten years earlier he had first toyed with the idea of converting Migros into a cooperative . He initially achieved this goal on a small scale in the canton of Ticino , where the Migros branch was structured as a cooperative from the start. After an amendment to the statutes in October 1935, Migros donated its net profit to charitable purposes after deducting taxes. Duttweiler made his conversion plans public on June 1, 1940. This step was preceded by internal disputes, as a result of which Chairman of the Board of Directors Hermann Walder left the company. The other board members wanted to dissuade Duttweiler from his plan and asked Adele Duttweiler-Bertschi to change her husband's mind. But she stood behind his decision and practically agreed to her own disinheritance. It only imposed the condition that one of the production companies, GD Produktion AG in Basel , remained in his possession for security reasons.

Giving away a company with a turnover of 72 million francs turned out to be a legally complex matter. Duttweiler, who paid out the remaining shareholders, wrote: “We have found out that it is a much more delicate task to give away money than to make money. […] The conversion of a cooperative into a stock corporation is regulated by law, does not cost taxes and is a simple company change. On the other hand, the unheard-of of the transformation of a stock corporation into a cooperative, that is not even planned! The only way left is liquidation and a new establishment. " The transfer of Migros, together with its branches and subsidiaries, into cooperative structures began in January 1941 and dragged on for twelve months. In the first year, Migros had 75,540 members. In addition to the employees, these were regular customers who had received a customer card during the hamster shopping wave of 1938/39. They were each given a share certificate worth CHF 30. In the following years the number of members of the cooperative increased continuously. The corporate structure comprised ten autonomous regional cooperatives, which together formed the Federation of Migros Cooperatives (MGB). The MGB kept its own production and took care of most of the purchasing, while the cooperatives mainly concentrated on sales.

Duttweiler named the main reason for the transformation of Migros to secure its charitable orientation. With much pathos he described the process as "Tatgemeinschaft federal type, built on the firm foundation of the Swiss Allmend idea , far from manchesterlich -American business sentiments." In addition to this socio-ethical motive, the economic framework also played a role. Contrary to earlier assertions, he admitted at the end of the 1950s that the equalization tax levied from 1938 onwards for the purpose of national defense and job creation was another reason, as cooperatives were exempt from it. In addition, cooperatives founded before 1935 were exempt from the branch ban, so he probably hoped that Migros would also benefit from a possible amendment to the law. A motive that should not be underestimated was his fear of the occupation of Switzerland by the German Reich , especially since, unlike other business leaders, he was far less optimistic about the course of the war. The expropriation of a cooperative with thousands of members would, in his opinion, have been much more difficult for a National Socialist regime than for a single millionaire. His opponents, on the other hand, saw the conversion as just a clever PR move.

Although Duttweiler invoked the ideals of the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers and made a reference to his father, there were clear differences from the conventional cooperative movement . He saw the benefit essentially in the fact that the members of the cooperative bought from Migros as consumers and thus increased the sales volume. This enabled Migros to lower its prices, which in turn benefited the customers' economic situation. The members' self-help was limited to customer loyalty to Migros, which empowered them to “serve customers”. For Duttweiler, the cooperative movement was therefore not an alternative to capitalism , but a harmonizing correction of commercial excesses and distortions. At the core of his vaguely outlined economic philosophy , which he called “social capital”, was social responsibility within a free, market-based social order that affirmed the market as an efficient economic selection principle. While the traditional, organically grown consumer cooperatives were pluralistic and pursued a cautious business strategy out of consideration for different political opinions, Duttweiler was considered an undisputed charismatic leader, which is why Migros maintained its expansionary thrust. In contrast to the cooperatives organized on the basis of democracy, Migros had a top-down structure with a concentration of power in the management of the FMC, while the cooperative councils elected in strike votes had no real decision-making authority and the cooperative members were only asked about a few strategic decisions. The cooperatives that arose in a single founding act were completely free from the influence of external investors, but were subject to certain predetermined principles of the FMC. As a result, as wanted by Duttweiler, they had more of the character of foundations.

The generosity was not limited to Migros. In September 1939, the unprofitable Monte Generoso Railway in Ticino had ceased operations. Duttweiler learned of the imminent demolition of this rack railway and spontaneously acquired it in March 1941. He handed them over to a newly founded cooperative, which repaired the systems and resumed operations. The reduction of the fare by almost two thirds resulted in a nine-fold increase in the number of passengers in the first year, which guaranteed the long-term survival of the railway. In 1925, the Duttweiler couple began to acquire property above Rüschlikon . Over the years a total of 45,000 m² of meadow and woodland came together. They had a modest house with a thatched roof built on the edge of the site. They commissioned the painter Hermann Gattiker to transform it into a park . Shortly after completion, they donated the “ Park im Grüene ” (including the house) to the Migros Cooperative Association for Christmas 1946 . At first it was open to the members of the cooperative and a little later to the general public. Luxury had meanwhile become completely unimportant for Duttweiler and he had a modest lifestyle. For example, he drove a Fiat Topolino , although its large and heavy stature made it difficult to fit into this small car. Basically, he took train journeys in third class. The thrift also extended to everyday office life: Envelopes had to be reused as notes, and he wrote his manuscripts on the back of the obituary notices that were sent to him.

Journalism and journalism

Duttweiler developed a brisk journalistic activity. The advertising he designed himself in the early years was deliberately aimed at housewives , the main customer segment. The first leaflet shortly before the start of sales began with the words: «To the housewife who has to calculate! - To the intelligent woman who can count ». It explained why the groceries could be offered at such low prices and ended with the bold threat of closing the shop if it was unsuccessful: “Either the old shopping habits, the advertising and the buzzwords will win - or the hoped-for popularity will emerge ; in this case we may be able to reduce the prices, otherwise we will have to give up this serious attempt to serve the consumer. " Although the vans caused a stir wherever they stopped, Migros also relied on advertising. This turned out to be difficult in that associations and competitors put the publishers of smaller newspapers under massive pressure, so that they often did not accept advertisements . In addition to the timetable and price list, the leaflets always contained a text section written by Duttweiler and Elsa Gasser with brief comments and analyzes as well as Migros' goals. This resulted in Migros - Die Brücke , a multi-page free newspaper that was distributed to all households in the catchment area and was the most important journalistic tool of the early years.

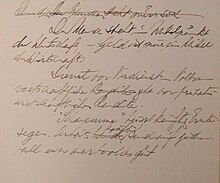

With increasing opposition, Duttweiler felt the need to communicate directly with his customers. He was his own press officer instead of delegating public relations like other entrepreneurs and remaining anonymous in the background. In the endeavor to put yourself at the center and thus to make yourself vulnerable, vanity may have played a certain role. His move into journalism was also a natural consequence of his sense of mission . For him, it wasn't just about selling goods as cheaply as possible, but also wanted to convey attitudes, confessions and demands and to be understood in principle. He went on to write longer articles, which from December 17, 1927 appeared weekly in the form of half-page advertisements in up to 30 newspapers; he called the concept newspaper in the newspaper . When individual publishers gave in to the pressure of Migros opponents and no longer accepted the advertisements, Duttweiler defended himself by prominently mentioning the newspapers that had dropped out and thus directing the anger of the loyal readership onto the publishers. Other publishers made compromises and only refused to publish the newspaper if it contained attacks on advertising companies. Duttweiler wrote 1350 of these text advertisements, in which he merged advertising and consumer politics, over the decades.

After being elected to the National Council, the Independent Group needed its own body. From November 12, 1935, Duttweiler brought out the weekly newspaper Die Tat . He viewed them as "a simple, serious weekly report sheet from the 7 Independents for their friends". As a motive for founding the newspaper, he also cited the defense against National Socialism in Switzerland: "It was the spring of the fronts in 1935. The screams of the Swiss Nazi disciples had to be countered with something juicy." Four years later, Duttweiler converted the deed into a daily newspaper that appeared for the first time on October 2, 1939 and maintained its anti-Nazi course. Duttweiler initially worked with enthusiasm, but withdrew more and more because it was difficult for him to report on current events. He often quarreled with the spirited editor-in-chief Erwin Jaeckle , and despite a print run of 40,000 copies, the act was hardly ever self-supporting (the result of an advertising boycott by branded goods, alcohol and tobacco manufacturers). Migros made up for the deficits, and construction contractor Ernst Göhner , who was friends with Duttweiler, also poured in money on a regular basis. One year after Migros was transformed into a cooperative, Wir Brückenbauer , a free weekly newspaper for all members of the cooperative , appeared for the first time on July 30, 1942 . With it, Duttweiler was able to get in much closer contact with his customers than with the newspaper in the newspaper ; Week after week he wrote the editorial .

For his publications Duttweiler wrote a total of almost 3000 articles, commentaries and glosses . They dealt with economic problems, political disputes as well as social and cultural issues, contained suggestions and appeals to authorities, first-hand reports from the court cases, but also humoristic things. When something particularly annoyed him, Duttweiler used sarcasm . A major concern for him were reflective texts on secular and religious holidays, in which he referred to historical events, the Bible and famous poets and thinkers. His writing style was strongly influenced by his personality, that is, his articles were mostly passionate, powerful and peppered with puns, idioms, literary quotations and pictorial descriptions. In 1948 Gasser described his way of working as follows: «Most articles are dictated at a stormy pace, you could almost say: spat out. The usual interludes - telephone, oil or coffee tasting, conversations about shopping and other dispositions - may interrupt the thread ten times, but do not throw the author off balance. [...] Thoughts and words rush, the understanding of the reader is expected to take a long leap, but there is also something in it. [...] His ambition as a journalist is to print something that interests the professor and the laundress and is understandable to both. "

Further political activity

Duttweiler continued to shape the party he co-founded, but because of his authoritarian leadership style and for ideological reasons, a rift developed between him and most of the LdU national councils, who perceived his social commitment as a "slide to the left". Particular displeasure aroused the fact that he had always spoken out against the ban on the Communist Party and supported an election list in the Geneva cantonal elections in 1942 that united supporters of the communist Léon Nicole and the fascist Georges Oltramare . Duttweiler had emphasized that it is more in line with Switzerland's values to include political extremes in the democratic process than to drive them and their voters into illegality. Another point of criticism was that in April 1943 he had been elected to the Zurich Cantonal Council without consulting the parliamentary group (which he then belonged to for eight years). When he announced his candidacy as a member of the National Council on June 15, 1943, the parliamentary group (with the exception of Otto PfÄNDER ) opposed him and accused him of arbitrariness. Within the party , “Dossier B”, presumably leaked by Federal Councilor Eduard von Steiger , made the rounds. In it, Marc Bloch, a former partner at Maritime Suisse SA , claimed that Duttweiler had commissioned him to donate CHF 12,800 for the election campaign of the communists Léon Nicole and André Ehrler . An investigative commission set up by the LdU came to the conclusion that Bloch's allegations were not true. When the assembly of delegates confirmed Duttweiler's candidacy on September 30th, there was a final break. A day later, the dissidents drew up their own electoral list, the "Independent-Free List". In the National Council elections on October 31, 1943 , the Duttweiler wing prevailed (he himself was elected in the Canton of Zurich). Heinrich Schnyder was the only dissident to win a seat and then resigned from the LdU.

Back in parliament, Duttweiler continued to suffer defeat after defeat as he hardly ever compromised. In 1944, in a motion , he demanded a law for up to two years of sufficient stocks of essential raw materials and food. Both chambers of parliament delayed his submission by more than four years. In view of the communists' seizure of power in Eastern Europe, Duttweiler was convinced that his concern was more topical than ever. The President of the National Council ended the session again on October 8, 1948 , without submitting the motion for discussion. Duttweiler had suspected this and had an acquaintance bring two stones to the Bundeshaus . Shortly after the session ended, he smashed two window panes in an adjoining room, from the inside, in protest. The incident, which Duttweiler described as the “last well-considered, albeit desperate, remedy” caused a sensation. The Basler Nachrichten wrote that the stone's throw was "not only psychologically but also psychiatrically interesting". When the motion was discussed two months later, it met with widespread opposition even from the co-signatories. Duttweiler's popularity, it did not hurt: On July 3, 1949 was held in Zurich and one of States -Ersatzwahl instead. Although he was a candidate just two weeks earlier, he achieved the best result. In the second ballot on September 11th, he clearly prevailed and entered the small parliamentary chamber. In the regular election of the Council of States on October 28, 1951, however, he was defeated by the FDP candidate Ernst Vaterlaus . At the same time, he had successfully run for membership in the canton of Bern and represented it until the end of his life.

Duttweiler and the LdU are increasingly relying on popular initiatives and optional referendums . These were mostly aimed at preventing or reversing dirigistic measures and emergency ordinances based on special powers. Duttweiler was not a doctrinal liberal who refused any state intervention, especially since he was in favor of short-term measures. However, he resolutely opposed permanent regulations and the transfer of extraordinary restraints of competition into ordinary law. The referenda prevented a proof of need for road transport (1951), a permit requirement for hotels (1952) and a restriction on the opening of craft shops (1954). There were defeats with the Agriculture Act (1952), the structure-preserving taxation of the tobacco industry (1952), the Dairy Industry Decree (1960) and the Clock Statute (1961). Initiatives for a right to work (1946), a cartel ban (1958) and the introduction of the 44-hour week (1958) also remained unsuccessful . Duttweiler was not directly involved in the people's initiative "Return to Direct Democracy" , but its adoption on September 11, 1949 benefited him. From now on it was no longer possible to withdraw urgent federal resolutions from the optional referendum, which made laws such as the branch ban practically unenforceable.

A political issue that touched Duttweiler emotionally was the state financial support for the Swiss abroad who had fled or been expelled to Switzerland during the Second World War and who had largely lost their property abroad. Two months before the end of the war, he set up a support committee. With the agreement on German assets in Switzerland agreed in May 1946 , 121 million francs were available for compensation, but implementation was delayed by years. Finally, in December 1953, the Federal Council presented the “Federal Decree on Extraordinary Assistance to War-Damaged Swiss Abroad” in order to set up a “dispensation fund” with the money that had still not been distributed. Duttweiler determined that only about one in ten beneficiaries would receive compensation and commissioned the propaganda film The Trial of the Twenty Thousand to point out the injustice. The LdU seized the referendum and prevailed in the referendum of June 20, 1954 against the resistance of all Federal Council parties. Although the Federal Council and Parliament promised to implement the will of the people, nothing happened again. Without informing anyone, Duttweiler went to Geneva on June 24, 1955 and went on a hunger strike in protest at the headquarters of the International Red Cross , which he broke off after four days. Another federal decree of June 13, 1957 takes into account around a fifth of all those entitled to benefits, the particularly needy. The support committee refused to be involved because it had lost confidence in the authorities.

Rapid expansion of Migros

When Migros was legally recognized as a self-help cooperative on January 1, 1945, it was no longer subject to the branch ban, but remained subject to mandatory registration for a year through a voluntary agreement with the trade association. With the final repeal of the law on January 1, 1946, there were no longer any restrictions. A long period of exponential growth began as a result of the post-war boom . Only 15 years later, sales exceeded the one billion franc mark; In 1961 Migros already had 585,630 members, 397 shops and 135 sales vehicles. On business trips to the USA, Duttweiler got to know self-service shops that were still unknown in Europe . He was initially reluctant to introduce this system as well, fearing that personal contact between customers and sales staff could be lost. Elsa Gasser , his economics advisor, however, pushed for an introduction as soon as possible and was able to convince him. Finally, on March 15, 1948, the first Swiss self-service shop opened in Zurich, just two months after the European premiere in St Albans at the British retail chain Tesco . In 1951, Migros began to expand into the non-food sector, and in 1952 it opened the first supermarkets in Europe in Basel and Zurich .

Duttweiler's position at the head of Migros was not unchallenged. In 1948, the Migros cooperatives demanded in the Romandie the approval of the sale of wine, which he left to carry out a ballot for the first time. 54.2% of the participating cooperative members spoke out against the sale of wine. In 1956, Duttweiler surprised the management bodies of Migros when he spoke out in favor of the introduction of a discount system (which he had fought vigorously against three decades earlier). When he didn't get through with his idea internally, he made use of his statutory rights and contacted the cooperative members directly. They clearly rejected his request with 72.9% of the votes. In the meantime the media in the USA had become aware of Duttweiler and, in contrast to the Swiss press, showed admiration for his successes. Numerous newspapers and magazines published articles and interviews. They were surprised to find that on the one hand he was considered “too American” in his homeland, on the other hand he had given up most of his fortune for idealistic reasons. The Boston Conference on Distribution , an organization of the City of Boston and its Chamber of Commerce, accepted him into their Hall of Fame in 1953 . In the same year, the Turkish government approached Duttweiler and asked him for support in setting up a sales system based on the Migros model. He traveled to Istanbul for negotiations and founded Migros Türk with local partners on April 1, 1954 , which then remained associated with the Swiss Migros for 20 years.

Outside of the food retail trade, Duttweiler also stood out for his wealth of ideas. On his initiative, between June 1946 and February 1947, Migros placed over 3,000 domestic helpers from the province of Trentino for Swiss families with many children, which prompted the Italian government to negotiate an agreement with Switzerland on the recruitment of workers. In July 1951, Duttweiler decided to do something about the high prices for taxi rides in Zurich. Just his announcement that he would import a hundred Vauxhall taxis from Great Britain caused a stir among the established taxi companies. Before the cars were even in Switzerland, they lowered the tariffs by around a third. Duttweiler had achieved what he wanted and agreed a "non-aggression pact" in the "taxi war". He sold 40 Vauxhall taxis to chauffeurs; the others ended up in Basel, where they also corrected prices. From August 1951, Duttweiler again pursued shipping projects. Together with Ernst Göhner , he founded the Reederei Zürich AG . A year later, the Stülcken shipyard in Hamburg completed two cargo ships on their behalf, which were named after the founder's wives, Adele and Amelia . In 1954, the Rheinreederei AG was added, which was involved in the Rhine shipping (both merged in 1963 to Rheinreederei Zürich AG ). Duttweiler found that Migros also had to get into the financial business because, in his opinion, the banks were neglecting small savers. Migros Bank was founded in 1957, and Secura insurance followed two years later .

Duttweiler was not successful with all of his ideas: An example of this is the failure of the clothing guild, which he founded in 1944 in the form of a cooperative and with which he wanted to expand the Migros principle to include the men's fashion trade. The guild united 17 retailers and seven manufacturers who designed joint collections and offered them at particularly favorable conditions. Due to various conceptual errors and a lack of sales, the clothes guild disbanded after five years. The expansion to Spain did not get beyond the planning phase . There, on April 14, 1960, Migros Ibérica was founded, which was supposed to cooperate with independent food retailers. After only one year, the project failed due to the strict credit restrictions imposed by Spanish banks.

Fight against international corporations and arbitrariness

In January 1947 Duttweiler resumed litigation and sued Nestlé for unfair competition. He accused the food company of incorrectly declaring the content of the coffee products Nescoré and Nescafé and of secretly reducing the fresh milk content of condensed milk . A year later, those responsible were sentenced to conditional prison terms and fines, while Nestlé had to correct the declarations. In the spring of 1947, Duttweiler learned from an informant that the neocide powder produced by the Basel chemical company J. R. Geigy , which had been sold to the Red Cross and the Swiss donation to fight a typhus epidemic in Romania , contained too little active substance to be effective. The Department of Economic Affairs then launched an investigation. In November 1949 J. R. Geigy suffered a defeat in the last instance and had to accept heavy fines and the return of the illegally obtained profit. In August 1947, Duttweiler launched a new attack on Unilever : He accused the “oil trust scoundrels” (as he consistently called the company management) of exercising their influence right up to the highest levels of government. Specifically, he claimed that Walter Gattiker, the director of the Unilever Trust owned oil and grease works SAIS , was promoted to colonel despite lack of qualifications; In return, Colonels Eugen Bircher and Renzo Lardelli were rewarded with seats on the SAIS board of directors. In May 1949 there was a sensational defamation trial before the jury court in Winterthur . Seconded by his lawyer Walter Baechi , Duttweiler used this platform to drag the machinations of Unilever to the public. On June 4, one month before the Council of States election, he was sentenced to ten days in prison and a fine of 10,000 francs for defamation. In the bridge builder he wrote that the fight was still worth it.

As early as 1929, Duttweiler had recognized that the gasoline price was far too high compared to the actual production costs . 25 years later, he had the opportunity to take action against the cartel of oil companies when he entered into negotiations with the independent oil trader Jean Arnet. He immediately hired him as director and entrusted him with founding the mineral oil company Migrol , which from March 1954 had an aggressive price policy in the heating oil trade and forced competition to lower prices. In September, Migrol opened its first petrol station in Geneva , which was soon followed by several others. The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal even reported on the "gasoline war" which then broke out and which had cut prices by an average of 15% by the end of the year . With Rheinreederei AG , Migrol had its own supply route to Rotterdam and Antwerp , which is why delivery boycotts were pointless. In order to be independent of the corporations in the processing of the crude oil, Duttweiler aimed at an independent refinery . In Germany he negotiated with Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard and Finance Minister Franz Etzel as well as with the state government of Lower Saxony about the construction of the Frisia oil works in Emden . With the support of the Girozentrale , the financing was mainly provided by thousands of small shareholders. After 14 months of construction, the refinery started operations on August 25, 1960. Only five years later, Migrol withdrew from the refining business due to a lack of profitability and sold the shares to Saarbergwerke .

In 1956, Duttweiler founded the Bureau against Office and Association Arbitrariness , which was supposed to help people who had "fallen under the wheels of the judiciary or the administration". He entrusted journalist Werner Schmid with its management , which was remarkable since he had led a sharp public controversy with the Migros founder for over two decades. For example, Schmid had examined it in the 1937 publication Duttweiler - x-rayed! referred to as a “man with the desire to rule” and a “Napoleonide [n]”. The office, financed by Migros, handled cases in which all legal remedies had been exhausted, often successfully, on a private basis.

Cultural promotion

In November 1943, in an article on bridge builders , Duttweiler called for people to learn more languages in view of the "impending breakout of peace" in order to contribute to international understanding. He was inspired to do this by a survey of cooperative members who wanted Migros to organize all kinds of courses. An Italian teacher offered him to teach Migros employees, but Duttweiler had bigger plans. In agreement with Migros, an advertisement appeared in March 1944 promoting language courses at unrivaled low prices. More than 1400 interested people registered, whereupon organizational structures had to be created quickly to cope with the unexpected rush. Duttweiler understood that adult education had to take place in a relaxed atmosphere; Teachers and students should be able to meet and talk to each other like in a club. With that the name for the new offer was found, Club School Migros . In addition to language courses, it soon also offered arts and crafts courses. Duttweiler later described the club schools as "plantations of goodwill" because they plowed that "no man's land that the profitable economy found too little interesting". From 1956, Migros also organized language trips abroad, which in 1960 were outsourced to the Eurocentres Foundation, which it supported .

The post-war consumer society , to which Duttweiler himself had contributed, began to become increasingly alien to him. He feared that the people would do too little for their cultural education in the face of the new prosperity, which would inevitably lead to a “dulling of prosperity”. According to him, growing material power always had to be accompanied by greater social and cultural services. That is why he saw it as his task to give access to culture to those “ordinary people” who were previously excluded from it for financial or social reasons. On his initiative, “Clubhouse Concerts” were held for the first time in 1947 - performances of classical music at affordable prices and without the need for expensive cloakrooms, for which Migros hired world-famous choirs, orchestras and conductors. Theatrical performances, visual arts, exhibitions and other cultural events were added later.

As early as 1941, Migros began to give away books to its members at regular intervals, for which it bought up remnants of literary works or published its own publications (mostly non-fiction books) with a large number of copies. This should make it possible for broad sections of the population to set up their own home library. In 1950, the founders of the book club Ex Libris turned to Duttweiler for assistance. Migros took part and took over Ex Libris six years later. The offer consisted of licensed editions of the most important publishers in the German-speaking area, from 1952 records and turntables were also on offer. In the mid-1950s, Duttweiler began buying works of art by contemporary Swiss artists, which were initially used to decorate the Migros offices. The collection, which has grown over the decades, formed the basis for the Migros Museum for Contemporary Art, which opened in 1996 .

Securing life's work and death

On December 29, 1950, Gottlieb and Adele Duttweiler published 15 jointly developed theses. As a kind of ideal legacy, they laid down the intellectual goals and moral values of Migros. They are not legally binding, but represent guidelines that executives and cooperative councils can refer to at any time. One of the most important theses was that people must be placed at the center of the economy. Two days earlier, the couple had founded the Gottlieb and Adele Duttweiler Foundation , which, especially after the death of its founders, will work to ensure “that the goals we set out to establish the Migros cooperatives are preserved and pursued”. Among other things, it is intended to "support all efforts which, in the spirit and spirit of the founders, are based on the free development of people in a liberal but socially responsible democratic economy".

The assembly of delegates of the Federation of Migros Cooperatives (MGB) discussed the revision of the statutes on March 30, 1957 . While new administrative structures for the fast-growing company were undisputed, Duttweiler's demand that culture should take on an equal footing with economic activity sparked a heated debate. He had to allow himself to be accused by numerous critics that he was too arrogant and interfered with the competencies of his department heads and directors. Even his removal did not seem out of the question. Finally Duttweiler prevailed with 56 to 35 votes. The statutes enshrined the ideas of the Duttweiler couple about the ideal, social, cultural and economic policy goals as well as other non-business obligations of Migros. In order to secure the necessary financial means on a permanent basis, the MGB and the affiliated cooperatives founded the Migros Culture Percentage based on the 15 theses . Since then, this has been fed from one percent of the wholesale sales of the MGB and half a percent of the retail sales of the cooperatives.