The Songs of Bilitis: Difference between revisions

Albinoni67 (talk | contribs) m internal link to Parnassianism |

|||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 23 users not shown) | |||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''The Songs of Bilitis''''' ({{IPAc-en|b|ɪ|ˈ|l|iː|t|ɪ|s}}; {{lang-fr|Les Chansons de Bilitis}}) is a collection of erotic, essentially [[lesbian]], poetry by [[Pierre Louÿs]] published in Paris in 1894. Since Louÿs claimed that he had translated the original poetry from Ancient Greek, this work is considered a [[pseudotranslation]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Venuti|first1=Lawrence|title=The Scandals of Translation|url=https://archive.org/details/scandalsoftransl0000venu|url-access=registration|date=1998|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|pages=[https://archive.org/details/scandalsoftransl0000venu/page/34 34–39]}}</ref> |

'''''The Songs of Bilitis''''' ({{IPAc-en|b|ɪ|ˈ|l|iː|t|ɪ|s}}; {{lang-fr|Les Chansons de Bilitis}}) is a collection of erotic, essentially [[lesbian]], poetry by [[Pierre Louÿs]] published in Paris in 1894. Since Louÿs claimed that he had translated the original poetry from Ancient Greek, this work is considered a [[pseudotranslation]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Venuti|first1=Lawrence|title=The Scandals of Translation|url=https://archive.org/details/scandalsoftransl0000venu|url-access=registration|date=1998|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|pages=[https://archive.org/details/scandalsoftransl0000venu/page/34 34–39]}}</ref> The poems were actually clever [[Fabulation|fabulations]], authored by Louÿs himself, and are still considered important literature. |

||

The poems are in the manner of [[Sappho]]; the collection's introduction claims they were found on the walls of a [[tomb]] in [[Cyprus]], written by a woman of [[Ancient Greece]] called '''Bilitis''' ({{Lang-el|Βιλιτις}}), a [[courtesan]] and contemporary of Sappho to whose life Louÿs dedicated a small section of the book. On publication, the volume deceived even expert scholars.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Skucha|first=Mateusz|date=2019|title=Bilitis. Między tekstem pornograficznym a tekstem lesbijskim|url=https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=903804|journal=Śląskie Studia Polonistyczne|language=Polish|issue= |

The poems are in the manner of [[Sappho]]; the collection's introduction claims they were found on the walls of a [[tomb]] in [[Cyprus]], written by a woman of [[Ancient Greece]] called '''Bilitis''' ({{Lang-el|Βιλιτις}}), a [[courtesan]] and contemporary of Sappho's to whose life Louÿs dedicated a small section of the book. On publication, the volume deceived even expert scholars.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Skucha|first=Mateusz|date=2019|title=Bilitis. Między tekstem pornograficznym a tekstem lesbijskim|url=https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=903804|journal=Śląskie Studia Polonistyczne|volume=1|language=Polish|issue=13|pages=113–130|issn=2084-0772}}</ref> |

||

Louÿs claimed the 143 prose poems, excluding 3 epitaphs, were entirely the work of this ancient |

Louÿs claimed the 143 prose poems, excluding 3 epitaphs, were entirely the work of this ancient poet—a place where she poured both her most intimate thoughts and most public actions, from childhood innocence in [[Pamphylia]] to the loneliness and chagrin of her later years. |

||

Although for the most part ''The Songs of Bilitis'' is original work, many of the poems were reworked epigrams from the ''[[Greek Anthology|Palatine Anthology]]'', and Louÿs even borrowed some verses from Sappho herself. The poems are a blend of mellow sensuality and polished style in the manner of [[Parnassianism]], but underneath run subtle Gallic undertones that Louÿs could never escape. |

Although for the most part ''The Songs of Bilitis'' is original work, many of the poems were reworked epigrams from the ''[[Greek Anthology|Palatine Anthology]]'', and Louÿs even borrowed some verses from Sappho herself. The poems are a blend of mellow sensuality and polished style in the manner of [[Parnassianism]], but underneath run subtle Gallic undertones that Louÿs could never escape. |

||

To lend authenticity to the forgery, Louÿs in the index listed some poems as "untranslated"; he even craftily fabricated an entire section of his book called "The Life of Bilitis", crediting a certain fictional archaeologist Herr G. Heim ("Mr. C. Cret" in German) as the discoverer of Bilitis' tomb. And though Louÿs displayed great knowledge of Ancient Greek culture, ranging from children's games in "Tortie Tortue" to application of scents in "Perfumes", the literary fraud was eventually exposed. This did little, however, to taint their literary value in readers' eyes, and Louÿs' open and sympathetic celebration of lesbian sexuality earned him sensation and historic significance. |

To lend authenticity to the forgery, Louÿs in the index listed some poems as "untranslated"; he even craftily fabricated an entire section of his book called "The Life of Bilitis", crediting a certain fictional archaeologist Herr G. Heim ("Mr. C. Cret" in German) as the discoverer of Bilitis's tomb. And though Louÿs displayed great knowledge of Ancient Greek culture, ranging from children's games in "Tortie Tortue" to application of scents in "Perfumes", the literary fraud was eventually exposed. This did little, however, to taint their literary value in readers' eyes, and Louÿs's open and sympathetic celebration of lesbian sexuality earned him sensation and historic significance. |

||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

[[File:Desert Flower NGM-v31-p261.jpg|thumb|right|150px|A dancer in [[Biskra]]]] |

[[File:Desert Flower NGM-v31-p261.jpg|thumb|right|150px|A dancer in [[Biskra]]]] |

||

In 1894 Louÿs, travelling in Italy with his friend Ferdinand Hérold, |

In 1894 Louÿs, travelling in Italy with his friend Ferdinand Hérold, grandson of the composer (1791–1831) of the same name,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9-Ferdinand_H%C3%A9rold |title = André-Ferdinand Hérold — Wikipédia}}</ref>{{Circular reference|date=April 2022}} met [[André Gide]], who described how he had just lost his virginity to a Berber girl named Meriem in the oasis resort-town of [[Biskra]] in [[Algeria]]; Gide urged his friends to go to Biskra and follow his example. The ''Songs of Bilitis'' are the result of Louÿs and Hérold's shared encounter with Meriem the dancing-girl, and the poems are dedicated to Gide with a special mention to "M.b.A", Meriem ben Atala.<ref>[https://archive.org/details/andregidelifeinp00sher <!-- quote=André Gide: a life in the present. --> Alan Sheridan, "André Gide: a life in the present", p. 101]</ref> |

||

==Basic structure== |

==Basic structure== |

||

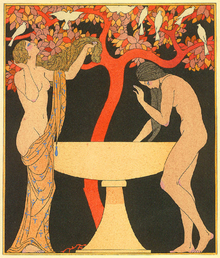

[[File:Bilitis and Mnasidika.png|thumb|Bilitis and Mnasidika as illustrated by Willy Pogány (1926).]] |

[[File:Bilitis and Mnasidika.png|thumb|Bilitis and Mnasidika as illustrated by Willy Pogány (1926).]] |

||

The ''Songs of Bilitis'' are separated into three cycles, each representative of a phase of Bilitis' life: [[Bucolic]]s in |

The ''Songs of Bilitis'' are separated into three cycles, each representative of a phase of Bilitis's life: [[Bucolic]]s in Pamphylia—childhood and first sexual encounters, [[Elegy|Elegies]] at Mytilene—indulgence in homosexual sensuality, and [[Epigram]]s in the Isle of Cyprus—life as a courtesan. Each cycle progresses toward a melancholy conclusion, each conclusion signalling a new, more complex chapter of experience, emotion, and sexual exploration. Each of these melancholy conclusions is demarcated by a tragic turn in Bilitis's relationships with others. In the first stage of her life, Bucolics, she falls in love with a young man but is then raped by him after he comes upon her napping in the woods; she marries him and has a child by him, but his abusive behavior compels her to abandon the relationship. In the second stage (Elegies), her relationship with her beloved Mnasidika turns cold and ends in estrangement, prompting her to relocate once again. Finally, in the Epigrams, in the Isle of Cyprus, despite her fame, she finds herself longing for Mnasidika. Ultimately, she and her beauty are largely forgotten; she pens her poems in silent obscurity, resolute in her knowledge that "those who will love when [she is] gone will sing [her] songs together, in the dark." |

||

One of Louÿs' technical accomplishments was to coincide Bilitis' growing maturity and emotional complexity with her changing views of divinity and the world around |

One of Louÿs's technical accomplishments was to coincide Bilitis's growing maturity and emotional complexity with her changing views of divinity and the world around her—after leaving Pamphylia and Mytilene, she becomes involved in intricate mysteries, moving away from a mythical world inhabited by satyrs and Naiads. This change is perhaps best reflected by the symbolic death of the satyrs and Naiads in "The Tomb of the Naiads". |

||

== Bilitis == |

== Bilitis == |

||

Louÿs dedicated a small section of the book to the fictional character of '''Bilitis''' ({{Lang-el|Βιλιτις}}), whom he invented for the book's purpose. He claimed she was a [[courtesan]] and contemporary of [[Sappho]], and the author of the poems he translated. He went so far as |

Louÿs dedicated a small section of the book to the fictional character of '''Bilitis''' ({{Lang-el|Βιλιτις}}), whom he invented for the book's purpose. He claimed she was a [[courtesan]] and contemporary of [[Sappho]]'s, and the author of the poems that he had translated. He went so far as not only to outline her life in a biographical sketch, but also to describe how her fictional tomb was discovered by a fictional archeological expedition, and include a list of additional, "untranslated", works by her.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

==Influence== |

==Influence== |

||

While the work was eventually shown to be a [[pseudotranslation]] by Louÿs |

While the work was eventually shown to be a [[pseudotranslation]] by Louÿs, initially it misled a number of scholars, such as {{ill|Jean Bertheroy|fr|Jean Bertheroy}}, who retranslated several poems without realizing they were fakes.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

Like the poems of Sappho, those of ''The Songs of Bilitis'' address themselves to [[Sapphic love]]. The book became a sought-after cult item among the 20th-century [[lesbian]] underground and was only reprinted officially in the 1970s. The expanded French second edition is reprinted in facsimile by [[Dover Books]] in America. This second edition had a title page that read: "This little book of antique love is respectfully dedicated to the young women of a future society." |

Like the poems of Sappho, those of ''The Songs of Bilitis'' address themselves to [[Sapphic love]]. The book became a sought-after cult item among the 20th-century [[lesbian]] underground and was only reprinted officially in the 1970s. The expanded French second edition is reprinted in facsimile by [[Dover Books]] in America. This second edition had a title page that read: "This little book of antique love is respectfully dedicated to the young women of a future society." |

||

In 1955 the [[Daughters of Bilitis]] was founded in San Francisco<ref>{{cite thesis|last=Perdue|first=Katherine Anne|date=June 2014|title=Writing Desire: The Love Letters of Frieda Fraser and Edith |

In 1955, the [[Daughters of Bilitis]] was founded in San Francisco<ref name="Perdue 276">{{cite thesis|last=Perdue|first=Katherine Anne|date=June 2014|title=Writing Desire: The Love Letters of Frieda Fraser and Edith Williams{{snd}}Correspondence and Lesbian Subjectivity in Early Twentieth Century Canada|type=PhD|publisher=[[York University]]|url=https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10315/28211/Perdue_Katherine__A_2014_PhD.pdf?sequence=2 |access-date=25 May 2017|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525175945/https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10315/28211/Perdue_Katherine__A_2014_PhD.pdf?sequence=2|archivedate=25 May 2017|location=Toronto, Canada|page=276}}</ref> as the [[List of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender firsts by year|first]]<ref name="Perdue 276"/> [[lesbian]] [[civil and political rights]] organization in the United States. In regard to its name, [[Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon]], two of the group's founders, said "If anyone asked us, we could always say we belong to a poetry club."<ref>Meeker, Martin. ''Contacts Desired: Gay and Lesbian Communications and Community, 1940s–1970s.'' p. 78. University of Chicago Press, 2006. {{ISBN|0226517357}}</ref> |

||

==Adaptations== |

==Adaptations== |

||

*Louÿs' close friend [[Claude Debussy]] |

*In 1897, Louÿs's close friend [[Claude Debussy]] set three of the poems—''La flûte de Pan'', ''La chevelure'' and ''Le tombeau des Naïades''—as songs for female voice and piano. The composer returned to the collection in a more elaborate fashion in 1900, creating ''Musique de scène pour les chansons de bilitis'' (also known as ''Chansons de bilitis'') for recitation of twelve of Louÿs's poems. These pieces were scored for two flutes, two harps and [[celesta]]. According to contemporary sources, the recitation and music were accompanied by ''tableaux vivants'' as well. Apparently, only one private performance of the entire creation took place, in Venice. Debussy did not publish the score in his lifetime, but he later adapted six of the twelve for piano as ''[[Six Epigraphes Antiques]]'' in 1914. |

||

*French composer and pianist [[Rita Strohl]] composed her settings of 12 ''Chansons de Bilitis'' in 1898. They were performed by [[Jane Bathori]]. There is a modern recording by Marianne Croux and Anne Bertin-Hugault.<ref>''[https://www.editionshortus.com/catalogue_fiche.php?prod_id=285 Rita Strohl : Douze Chants de Bilitis]'', Hortus 213 (2022)</ref> |

|||

*[[Claude Debussy]]'s ''Chansons de Bilitis'' received its first performance on February 7 1901 in Paris. Based on poems by Pierre Louys, this piece is scored for two flutes, two harps and celesta but is different from another work of the same name by Debussy, which is a group of songs. Today's performance includes narrator and mime; Debussy later incorporates the music into his ''[[Six Epigraphes Antiques]]'' for piano duo. |

|||

*French composer [[Charles Koechlin]] completed his five ''Chansons de Bilitis'', Op.39 between 1898 and 1908. The first complete performance was on 29 January 1918 by Jane Bathori and [[Andrée Vaurabourg]]. They were published in 1923.<ref>''[https://imslp.org/wiki/Chansons_de_Bilitis,_Op.39_(Koechlin,_Charles) Chansons de Bilitis, Op.39 (Koechlin, Charles)]'', score at IMSLP</ref> |

|||

*In 1932 [[Roman Maciejewski]] set some poems to music as well.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

*[[ |

*Brazilian composer [[Luciano Gallet]] set his ''Deux chansons de Bilitis'' for three voices and piano in 1920. |

||

*Polish composer [[Roman Maciejewski]] published ''The Songs of Bilitis'' (translated into Polish by [[Leopold Staff]]) for soprano & orchestra in 1935.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

*[[Joseph Kosma]]'s ''comédie musicale'' (or operetta) ''Les chansons de Bilitis'' was produced in Paris in 1954 at the [[Théâtre des Capucines]].<ref>[https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/rehearsal-of-the-chansons-de-bilitis-of-joseph-kosma-news-photo/56229105 Rehearsal of the Chansons de Bilitis, Getty Images, February 1954]</ref> |

|||

*[[Michael Findlay (filmmaker)|Michael Findlay]] and [[Roberta Findlay]] made a 1966 [[sexploitation]] film titled ''Take Me Naked'' which features narrated passages from ''The Songs of Bilitis''. In the film, the main character is shown in bed reading the collected works of Pierre Louÿs. He then has a series of erotic dreams depicting nude or scantily dressed women while a female voice narrates passages of the Bilitis poetry. |

*[[Michael Findlay (filmmaker)|Michael Findlay]] and [[Roberta Findlay]] made a 1966 [[sexploitation]] film titled ''Take Me Naked'' which features narrated passages from ''The Songs of Bilitis''. In the film, the main character is shown in bed reading the collected works of Pierre Louÿs. He then has a series of erotic dreams depicting nude or scantily dressed women while a female voice narrates passages of the Bilitis poetry. |

||

*The 1977 French film ''[[Bilitis (film)|Bilitis]]'', directed by [[David Hamilton (British photographer)|David Hamilton]] and starring [[Patti D'Arbanville]] and Mona Kristensen, was based on Louÿs' book, as stated in the opening credits. It concerns a twentieth century girl and her sexual awakening, but the British magazine ''[[Time Out (magazine)|Time Out]]'' said that, "surprisingly, a strong hint of Louys' erotic spirit survives, transmitted mainly through the effective playing and poise of the two leading characters."<ref>{{cite web |title=Bilitis |url=https://www.timeout.com/london/film/bilitis |website=Time Out |accessdate=10 July 2019 |archive-date=26 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200426201958/https://www.timeout.com/london/film/bilitis |url-status=dead }}{{ |

*The 1977 French film ''[[Bilitis (film)|Bilitis]]'', directed by [[David Hamilton (British photographer)|David Hamilton]] and starring [[Patti D'Arbanville]] and Mona Kristensen, was based on Louÿs's book, as stated in the opening credits. It concerns a twentieth century girl and her sexual awakening, but the British magazine ''[[Time Out (magazine)|Time Out]]'' said that, "surprisingly, a strong hint of Louys' erotic spirit survives, transmitted mainly through the effective playing and poise of the two leading characters."<ref>{{cite web |title=Bilitis |url=https://www.timeout.com/london/film/bilitis |website=Time Out |accessdate=10 July 2019 |archive-date=26 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200426201958/https://www.timeout.com/london/film/bilitis |url-status=dead }} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200426201958/https://www.timeout.com/london/film/bilitis |date=26 April 2020 }}</ref> |

||

*More recently ''Songs of Bilitis'', a play adapted from the poems by Katie Polebaum with music by [[Ego Plum]], was performed by [[Rogue Artists Ensemble]] under a commission from the [[Getty Villa]] in Los Angeles. |

*More recently ''Songs of Bilitis'', a play adapted from the poems by Katie Polebaum with music by [[Ego Plum]], was performed by [[Rogue Artists Ensemble]] under a commission from the [[Getty Villa]] in Los Angeles. |

||

In 2010, the faculty and students of [[Southwestern University]] (Georgetown, Texas) performed the complete corpus of Debussy's Bilitis-inspired music, together with original musical compositions and one original poem inspired by the story of Bilitis. The performances featured a reconstruction of the 1901 performance using pantomime, recitation, and ''tableaux vivants''. It also included a modern "deconstruction" of the Bilitis story, also using pantomime and tableaux vivants, to the music of Debussy's ''6 Epigraphes antiques'', much of which is based on the music used for the 1901 performance. The theatrical performances were directed by Kathleen Juhl, who also performed the recitation of the poems. Debussy's 3 Chansons de Bilitis were performed by mezzo-soprano Carol Kreuscher and pianist Kiyoshi Tamagawa in Victoria Star Varner's megalographic installation ''The Mysteries Revisited'', which was inspired by the [[Villa of the Mysteries]] and addresses some of the themes present in Louÿs' Bilitis poems.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.southwestern.edu/sarofim/bilitis/ |title=Archived copy |access-date=2015-09-23 |archive-date=2015-09-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923060417/http://www.southwestern.edu/sarofim/bilitis/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

== Translations == |

== Translations == |

||

The book was translated |

The book was translated into Polish twice, in 1920 by [[Leopold Staff]] and in 2010 by [[Robert Stiller]].<ref name=":0" /> |

||

English translations: |

|||

*Horace Manchester Brown in 1904. "Privately printed for members of The Aldus Society" (https://openlibrary.org/books/OL24152668M/The_songs_of_Bilitis) |

|||

*Alvah C. Bessie in 1926. "Privately printed for subscribers" (https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/sob/sob000.htm) |

|||

*H.M. Bird in 1931. Argus Books. |

|||

*J. Rolf in 2013. |

|||

==Illustrations== |

==Illustrations== |

||

''The Songs of Bilitis'' has been illustrated extensively by numerous artists. |

''The Songs of Bilitis'' has been illustrated extensively by numerous artists. |

||

The most famous |

The most famous artist to illustrate the book was [[Louis Icart]], while the most famous illustrations were done by [[Willy Pogany]] for a 1926 privately circulated English language translation: drawn in an [[art-deco]] style, with numerous visual puns on sexual objects.{{citation needed|date=August 2018}} |

||

Other artists have been [[Georges Barbier]], [[Edouard Chimot]], [[Jeanne Mammen]], [[Pascal Pia]], [[Joseph Kuhn-Régnier]], [[Sigismunds Vidbergs]], Pierre Leroy, Alméry Lobel Riche, Suzanne Ballivet, Pierre Lissac, Paul-Emile Bécat, Monique Rouver, Génia Minache, Lucio Milandre, A-E Marty, J.A. Bresval |

Other artists have been [[Georges Barbier]], [[Edouard Chimot]], [[Jeanne Mammen]], [[Pascal Pia]], [[Joseph Kuhn-Régnier]], [[Sigismunds Vidbergs]], Pierre Leroy, Alméry Lobel Riche, [[Suzanne Ballivet]], Pierre Lissac, Paul-Emile Bécat, Monique Rouver, Génia Minache, Lucio Milandre, A-E Marty, J.A. Bresval, James Fagan and Albert Gaeng from Geneva.{{citation needed|date=August 2018}} |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 96: | Line 103: | ||

* [http://traffic.libsyn.com/gardnermuseum/debussy_chansons.mp3 Debussy's ''Trois Chansons de Bilitis''] performed by [[Sasha Cooke]] (mezzo-soprano) and Pei-Yao Wang (piano) at the [[Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum]] in [[MP3]] format |

* [http://traffic.libsyn.com/gardnermuseum/debussy_chansons.mp3 Debussy's ''Trois Chansons de Bilitis''] performed by [[Sasha Cooke]] (mezzo-soprano) and Pei-Yao Wang (piano) at the [[Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum]] in [[MP3]] format |

||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Songs Of Bilitis}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Songs Of Bilitis}} |

||

[[Category:1894 books]] |

[[Category:1894 books]] |

||

| Line 102: | Line 110: | ||

[[Category:Erotic poetry]] |

[[Category:Erotic poetry]] |

||

[[Category:LGBT literature in France]] |

[[Category:LGBT literature in France]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Ancient Greece in art and culture]] |

||

[[Category:Ancient Greek erotic literature]] |

[[Category:Ancient Greek erotic literature]] |

||

[[Category:1890s LGBT literature]] |

[[Category:1890s LGBT literature]] |

||

[[Category:Works by Pierre Louÿs]] |

|||

[[Category:LGBT poetry]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 09:31, 16 January 2024

Illustration by Georges Barbier for The Songs of Bilitis | |

| Author | Pierre Louÿs |

|---|---|

| Original title | Les Chansons de Bilitis |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Poetry, erotica |

Publication date | 1894 |

| Media type | |

The Songs of Bilitis (/bɪˈliːtɪs/; French: Les Chansons de Bilitis) is a collection of erotic, essentially lesbian, poetry by Pierre Louÿs published in Paris in 1894. Since Louÿs claimed that he had translated the original poetry from Ancient Greek, this work is considered a pseudotranslation.[1] The poems were actually clever fabulations, authored by Louÿs himself, and are still considered important literature.

The poems are in the manner of Sappho; the collection's introduction claims they were found on the walls of a tomb in Cyprus, written by a woman of Ancient Greece called Bilitis (Greek: Βιλιτις), a courtesan and contemporary of Sappho's to whose life Louÿs dedicated a small section of the book. On publication, the volume deceived even expert scholars.[2]

Louÿs claimed the 143 prose poems, excluding 3 epitaphs, were entirely the work of this ancient poet—a place where she poured both her most intimate thoughts and most public actions, from childhood innocence in Pamphylia to the loneliness and chagrin of her later years.

Although for the most part The Songs of Bilitis is original work, many of the poems were reworked epigrams from the Palatine Anthology, and Louÿs even borrowed some verses from Sappho herself. The poems are a blend of mellow sensuality and polished style in the manner of Parnassianism, but underneath run subtle Gallic undertones that Louÿs could never escape.

To lend authenticity to the forgery, Louÿs in the index listed some poems as "untranslated"; he even craftily fabricated an entire section of his book called "The Life of Bilitis", crediting a certain fictional archaeologist Herr G. Heim ("Mr. C. Cret" in German) as the discoverer of Bilitis's tomb. And though Louÿs displayed great knowledge of Ancient Greek culture, ranging from children's games in "Tortie Tortue" to application of scents in "Perfumes", the literary fraud was eventually exposed. This did little, however, to taint their literary value in readers' eyes, and Louÿs's open and sympathetic celebration of lesbian sexuality earned him sensation and historic significance.

Background[edit]

In 1894 Louÿs, travelling in Italy with his friend Ferdinand Hérold, grandson of the composer (1791–1831) of the same name,[3][circular reference] met André Gide, who described how he had just lost his virginity to a Berber girl named Meriem in the oasis resort-town of Biskra in Algeria; Gide urged his friends to go to Biskra and follow his example. The Songs of Bilitis are the result of Louÿs and Hérold's shared encounter with Meriem the dancing-girl, and the poems are dedicated to Gide with a special mention to "M.b.A", Meriem ben Atala.[4]

Basic structure[edit]

The Songs of Bilitis are separated into three cycles, each representative of a phase of Bilitis's life: Bucolics in Pamphylia—childhood and first sexual encounters, Elegies at Mytilene—indulgence in homosexual sensuality, and Epigrams in the Isle of Cyprus—life as a courtesan. Each cycle progresses toward a melancholy conclusion, each conclusion signalling a new, more complex chapter of experience, emotion, and sexual exploration. Each of these melancholy conclusions is demarcated by a tragic turn in Bilitis's relationships with others. In the first stage of her life, Bucolics, she falls in love with a young man but is then raped by him after he comes upon her napping in the woods; she marries him and has a child by him, but his abusive behavior compels her to abandon the relationship. In the second stage (Elegies), her relationship with her beloved Mnasidika turns cold and ends in estrangement, prompting her to relocate once again. Finally, in the Epigrams, in the Isle of Cyprus, despite her fame, she finds herself longing for Mnasidika. Ultimately, she and her beauty are largely forgotten; she pens her poems in silent obscurity, resolute in her knowledge that "those who will love when [she is] gone will sing [her] songs together, in the dark."

One of Louÿs's technical accomplishments was to coincide Bilitis's growing maturity and emotional complexity with her changing views of divinity and the world around her—after leaving Pamphylia and Mytilene, she becomes involved in intricate mysteries, moving away from a mythical world inhabited by satyrs and Naiads. This change is perhaps best reflected by the symbolic death of the satyrs and Naiads in "The Tomb of the Naiads".

Bilitis[edit]

Louÿs dedicated a small section of the book to the fictional character of Bilitis (Greek: Βιλιτις), whom he invented for the book's purpose. He claimed she was a courtesan and contemporary of Sappho's, and the author of the poems that he had translated. He went so far as not only to outline her life in a biographical sketch, but also to describe how her fictional tomb was discovered by a fictional archeological expedition, and include a list of additional, "untranslated", works by her.[2]

Influence[edit]

While the work was eventually shown to be a pseudotranslation by Louÿs, initially it misled a number of scholars, such as Jean Bertheroy, who retranslated several poems without realizing they were fakes.[2]

Like the poems of Sappho, those of The Songs of Bilitis address themselves to Sapphic love. The book became a sought-after cult item among the 20th-century lesbian underground and was only reprinted officially in the 1970s. The expanded French second edition is reprinted in facsimile by Dover Books in America. This second edition had a title page that read: "This little book of antique love is respectfully dedicated to the young women of a future society."

In 1955, the Daughters of Bilitis was founded in San Francisco[5] as the first[5] lesbian civil and political rights organization in the United States. In regard to its name, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, two of the group's founders, said "If anyone asked us, we could always say we belong to a poetry club."[6]

Adaptations[edit]

- In 1897, Louÿs's close friend Claude Debussy set three of the poems—La flûte de Pan, La chevelure and Le tombeau des Naïades—as songs for female voice and piano. The composer returned to the collection in a more elaborate fashion in 1900, creating Musique de scène pour les chansons de bilitis (also known as Chansons de bilitis) for recitation of twelve of Louÿs's poems. These pieces were scored for two flutes, two harps and celesta. According to contemporary sources, the recitation and music were accompanied by tableaux vivants as well. Apparently, only one private performance of the entire creation took place, in Venice. Debussy did not publish the score in his lifetime, but he later adapted six of the twelve for piano as Six Epigraphes Antiques in 1914.

- French composer and pianist Rita Strohl composed her settings of 12 Chansons de Bilitis in 1898. They were performed by Jane Bathori. There is a modern recording by Marianne Croux and Anne Bertin-Hugault.[7]

- French composer Charles Koechlin completed his five Chansons de Bilitis, Op.39 between 1898 and 1908. The first complete performance was on 29 January 1918 by Jane Bathori and Andrée Vaurabourg. They were published in 1923.[8]

- Brazilian composer Luciano Gallet set his Deux chansons de Bilitis for three voices and piano in 1920.

- Polish composer Roman Maciejewski published The Songs of Bilitis (translated into Polish by Leopold Staff) for soprano & orchestra in 1935.[2]

- Joseph Kosma's comédie musicale (or operetta) Les chansons de Bilitis was produced in Paris in 1954 at the Théâtre des Capucines.[9]

- Michael Findlay and Roberta Findlay made a 1966 sexploitation film titled Take Me Naked which features narrated passages from The Songs of Bilitis. In the film, the main character is shown in bed reading the collected works of Pierre Louÿs. He then has a series of erotic dreams depicting nude or scantily dressed women while a female voice narrates passages of the Bilitis poetry.

- The 1977 French film Bilitis, directed by David Hamilton and starring Patti D'Arbanville and Mona Kristensen, was based on Louÿs's book, as stated in the opening credits. It concerns a twentieth century girl and her sexual awakening, but the British magazine Time Out said that, "surprisingly, a strong hint of Louys' erotic spirit survives, transmitted mainly through the effective playing and poise of the two leading characters."[10]

- More recently Songs of Bilitis, a play adapted from the poems by Katie Polebaum with music by Ego Plum, was performed by Rogue Artists Ensemble under a commission from the Getty Villa in Los Angeles.

Translations[edit]

The book was translated into Polish twice, in 1920 by Leopold Staff and in 2010 by Robert Stiller.[2]

English translations:

- Horace Manchester Brown in 1904. "Privately printed for members of The Aldus Society" (https://openlibrary.org/books/OL24152668M/The_songs_of_Bilitis)

- Alvah C. Bessie in 1926. "Privately printed for subscribers" (https://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/sob/sob000.htm)

- H.M. Bird in 1931. Argus Books.

- J. Rolf in 2013.

Illustrations[edit]

The Songs of Bilitis has been illustrated extensively by numerous artists.

The most famous artist to illustrate the book was Louis Icart, while the most famous illustrations were done by Willy Pogany for a 1926 privately circulated English language translation: drawn in an art-deco style, with numerous visual puns on sexual objects.[citation needed]

Other artists have been Georges Barbier, Edouard Chimot, Jeanne Mammen, Pascal Pia, Joseph Kuhn-Régnier, Sigismunds Vidbergs, Pierre Leroy, Alméry Lobel Riche, Suzanne Ballivet, Pierre Lissac, Paul-Emile Bécat, Monique Rouver, Génia Minache, Lucio Milandre, A-E Marty, J.A. Bresval, James Fagan and Albert Gaeng from Geneva.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Venuti, Lawrence (1998). The Scandals of Translation. New York: Routledge. pp. 34–39.

- ^ a b c d e Skucha, Mateusz (2019). "Bilitis. Między tekstem pornograficznym a tekstem lesbijskim". Śląskie Studia Polonistyczne (in Polish). 1 (13): 113–130. ISSN 2084-0772.

- ^ "André-Ferdinand Hérold — Wikipédia".

- ^ Alan Sheridan, "André Gide: a life in the present", p. 101

- ^ a b Perdue, Katherine Anne (June 2014). Writing Desire: The Love Letters of Frieda Fraser and Edith Williams – Correspondence and Lesbian Subjectivity in Early Twentieth Century Canada (PDF) (PhD). Toronto, Canada: York University. p. 276. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Meeker, Martin. Contacts Desired: Gay and Lesbian Communications and Community, 1940s–1970s. p. 78. University of Chicago Press, 2006. ISBN 0226517357

- ^ Rita Strohl : Douze Chants de Bilitis, Hortus 213 (2022)

- ^ Chansons de Bilitis, Op.39 (Koechlin, Charles), score at IMSLP

- ^ Rehearsal of the Chansons de Bilitis, Getty Images, February 1954

- ^ "Bilitis". Time Out. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2019. Archived 26 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

External links[edit]

- The Songs of Bilitis, full text of 1926 English translation by Alvah C. Bessie

- Rogue Artists Ensemble's theatrical adaptation The Songs of Bilitis

- Debussy's Trois Chansons de Bilitis performed by Sasha Cooke (mezzo-soprano) and Pei-Yao Wang (piano) at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in MP3 format