Religion in Botswana: Difference between revisions

m Spelling/grammar/punctuation/typographical correction |

m Copyedit (minor) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

}}}} |

}}}} |

||

[[Botswana]] is a [[Christianity|Christian]] majority nation, and allows [[freedom of religion|freedom of religious practice]].<ref name=report/> A country of an estimated 2.26 million people in 2015,<ref name="World Bank Group 2016">{{cite web | title=Botswana | website=World Bank Group | date=2016-09-19 | url=http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/botswana | author = World Bank Group | access-date=2016-10-18}}</ref> [[Christianity]] arrived in Botswana in mid 1870s, with the arrival of [[Christian mission|Christian missionaries]]. The conversion process was quicker than neighboring southern African countries |

[[Botswana]] is a [[Christianity|Christian]] majority nation, and allows [[freedom of religion|freedom of religious practice]].<ref name=report/> A country of an estimated 2.26 million people in 2015,<ref name="World Bank Group 2016">{{cite web | title=Botswana | website=World Bank Group | date=2016-09-19 | url=http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/botswana | author = World Bank Group | access-date=2016-10-18}}</ref> [[Christianity]] arrived in Botswana in mid 1870s, with the arrival of [[Christian mission|Christian missionaries]]. The conversion process was quicker than neighboring southern African countries because regional hereditary tribal chiefs locally called ''[[Kgosi|Dikgosi]]'' converted to Christianity, which triggered the entire group they led to convert as well.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/> |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

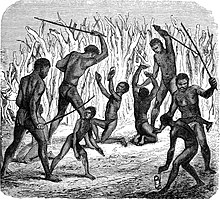

[[File:Seven Years in South Africa, page 397, training the boys.jpg|thumb|left|Beating boys as a part of the Bogwera ceremony (1870s)]] |

[[File:Seven Years in South Africa, page 397, training the boys.jpg|thumb|left|Beating boys as a part of the Bogwera ceremony (1870s)]] |

||

[[File:Hindu temple gaborone01.jpg|thumb|250px|BAPS Swaminarayan Hindu Mission, [[Gaborone]].]] |

[[File:Hindu temple gaborone01.jpg|thumb|250px|BAPS Swaminarayan Hindu Mission, [[Gaborone]].]] |

||

After the arrival of Christianity in Botswana, the missionaries established Bible schools and attempted to end old practices such as ''Bogwera'' (the tribe's traditional initiation ceremony into manhood) and ''Bojale'' (a girl's initiation ceremony into womanhood after she reached puberty), both of which were traditionally linked to the social acceptance of someone readiness to marry as well the right to inherit property.{{Citation needed|date=July 2020}} These practices continued to be in vogue in private, despite missionary efforts to end them.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/> The Christian missionaries, particularly the [[London Missionary Society]], |

After the arrival of Christianity in Botswana, the missionaries established Bible schools and attempted to end old practices such as ''Bogwera'' (the tribe's traditional initiation ceremony into manhood) and ''Bojale'' (a girl's initiation ceremony into womanhood after she reached puberty), both of which were traditionally linked to the social acceptance of someone's readiness to marry as well the right to inherit property.{{Citation needed|date=July 2020}} These practices continued to be in vogue in private, despite missionary efforts to end them.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/> The Christian missionaries, particularly the [[London Missionary Society]], were politically involved as interpreters between the tribal chiefs and the colonial administrators.<ref name="Bongmba2015p389">{{cite book|author=Elias Kifon Bongmba|title=Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9pZACwAAQBAJ&pg=PA389|year=2015|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-50577-7|pages=389–390}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Location Botswana AU Africa.svg|thumb|left|160px|Botswana.]] |

[[File:Location Botswana AU Africa.svg|thumb|left|160px|Botswana.]] |

||

After Botswana gained independence in 1966 from the colonial rule, senior Christian mission officials and [[Reverend]]s served as the first Speaker of the National Assembly and as officials in the new government.<ref name="Bongmba2015p389"/> In 1970s, its new leaders reviewed the Christian colonial curriculum in schools, revised it in order to restore traditional values based on pre-Christian religious ideas, such as ''Kagisanyo'' and ''Botho'', respectively harmony and humanism.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/><ref name="Shillington163"/> Bogwera and Bojale were re-introduced.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/> The new leaders also adopted a policy of religious tolerance and freedom, an approach towards religion in Botswana that continues in the 21st century.<ref name=report/> However, the school curriculum remains largely as before with Christian terminology and ideologies.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/> |

After Botswana gained independence in 1966 from the colonial rule, senior Christian mission officials and [[Reverend]]s served as the first Speaker of the National Assembly and as officials in the new government.<ref name="Bongmba2015p389"/> In 1970s, its new leaders reviewed the Christian colonial curriculum in schools, revised it in order to restore traditional values based on pre-Christian religious ideas, such as ''Kagisanyo'' and ''Botho'', respectively harmony and humanism.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/><ref name="Shillington163"/> Bogwera and Bojale were re-introduced.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/> The new leaders also adopted a policy of religious tolerance and freedom, an approach towards religion in Botswana that continues in the 21st century.<ref name=report/> However, the school curriculum remains largely as before, with Christian terminology and ideologies.<ref name="SwartzTaylor2013p67"/> |

||

An estimated 70 percent of Botswana citizens in 2001 identified themselves as [[Christians]].<ref name=report>[https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2007/90083.htm International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Botswana]. United States [[Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor]] (September 14, 2007). ''This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the [[public domain]].''</ref> In 2006, a Botswana government published report listed 63 percent of its citizens were Christians of various denominations, about 27 percent said their religion |

An estimated 70 percent of Botswana citizens in 2001 identified themselves as [[Christians]].<ref name=report>[https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2007/90083.htm International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Botswana]. United States [[Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor]] (September 14, 2007). ''This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the [[public domain]].''</ref> In 2006, a Botswana government published report listed 63 percent of its citizens were Christians of various denominations, about 27 percent said their religion was “God,” about 8 percent claimed to have no religion, 2 percent were adherents of the traditional indigenous religion Badimo, and all other religious groups (Buddhism, Hindu, Islam, Judaism, others) in total were less than 1 percent of Botswana population.<ref name="U.S. Department of State2016">{{cite web | title=International Religious Freedom Report for 2015, Country Report: Botswana | author=U.S. Department of State | year=2016| url=https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm | access-date=2016-10-18}}</ref> Of the others category, Muslims were 0.4% and Hindus were 0.3% of the total population.<ref>{{cite book|author=Pew Research Center|publisher= PRG, Washington DC|title = Religious Composition by Country: Global Religious Landscape |url=http://www.pewforum.org/files/2012/12/globalReligion-tables.pdf|year=2012}}</ref> |

||

The constitution of Botswana protects the freedom of religion |

The constitution of Botswana protects the freedom of religion and allows missionaries and proselytizers to work freely after they register with the government, but forced conversion is against the law. There is no state religion in Botswana.<ref name=report/><ref name="U.S. Department of State2016"/> |

||

Botswana recognizes only Christian holidays as public holidays. The nationwide religious observations include Good Friday, Easter Monday, Ascension Day, and Christmas.<ref name=report/><ref name="U.S. Department of State2016"/> |

Botswana recognizes only Christian holidays as public holidays. The nationwide religious observations include Good Friday, Easter Monday, Ascension Day, and Christmas.<ref name=report/><ref name="U.S. Department of State2016"/> |

||

Revision as of 20:21, 27 February 2021

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Botswana |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Religion in Botswana (Pew Research)[1]

Botswana is a Christian majority nation, and allows freedom of religious practice.[2] A country of an estimated 2.26 million people in 2015,[3] Christianity arrived in Botswana in mid 1870s, with the arrival of Christian missionaries. The conversion process was quicker than neighboring southern African countries because regional hereditary tribal chiefs locally called Dikgosi converted to Christianity, which triggered the entire group they led to convert as well.[4]

History

Before the arrival of Christianity, Animism was the prevailing belief system of the country.[citation needed]

Later the Dikgosi converted in the belief that the Christian missionaries would help them source guns to resist Afrikaner trekkers from south as well as help resist imperialist white foreigners.[4] Some scholars place the initial contacts between Christian missionaries and Bechuanaland (the old name of Botswana) a few decades earlier.[5]

After the arrival of Christianity in Botswana, the missionaries established Bible schools and attempted to end old practices such as Bogwera (the tribe's traditional initiation ceremony into manhood) and Bojale (a girl's initiation ceremony into womanhood after she reached puberty), both of which were traditionally linked to the social acceptance of someone's readiness to marry as well the right to inherit property.[citation needed] These practices continued to be in vogue in private, despite missionary efforts to end them.[4] The Christian missionaries, particularly the London Missionary Society, were politically involved as interpreters between the tribal chiefs and the colonial administrators.[6]

After Botswana gained independence in 1966 from the colonial rule, senior Christian mission officials and Reverends served as the first Speaker of the National Assembly and as officials in the new government.[6] In 1970s, its new leaders reviewed the Christian colonial curriculum in schools, revised it in order to restore traditional values based on pre-Christian religious ideas, such as Kagisanyo and Botho, respectively harmony and humanism.[4][5] Bogwera and Bojale were re-introduced.[4] The new leaders also adopted a policy of religious tolerance and freedom, an approach towards religion in Botswana that continues in the 21st century.[2] However, the school curriculum remains largely as before, with Christian terminology and ideologies.[4]

An estimated 70 percent of Botswana citizens in 2001 identified themselves as Christians.[2] In 2006, a Botswana government published report listed 63 percent of its citizens were Christians of various denominations, about 27 percent said their religion was “God,” about 8 percent claimed to have no religion, 2 percent were adherents of the traditional indigenous religion Badimo, and all other religious groups (Buddhism, Hindu, Islam, Judaism, others) in total were less than 1 percent of Botswana population.[7] Of the others category, Muslims were 0.4% and Hindus were 0.3% of the total population.[8]

The constitution of Botswana protects the freedom of religion and allows missionaries and proselytizers to work freely after they register with the government, but forced conversion is against the law. There is no state religion in Botswana.[2][7]

Botswana recognizes only Christian holidays as public holidays. The nationwide religious observations include Good Friday, Easter Monday, Ascension Day, and Christmas.[2][7]

See also

- Badimo

- Bahá'í Faith in Botswana

- Botswana Council of Churches

- Christianity in Botswana

- Freedom of religion in Botswana

- Hinduism in Botswana

- Irreligion in Botswana

- Islam in Botswana

References

- ^ Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project: Botswana. Pew Research Center. 2010.

- ^ a b c d e International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Botswana. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ World Bank Group (2016-09-19). "Botswana". World Bank Group. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ a b c d e f Sharlene Swartz; Monica Taylor (2013). Moral Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Culture, Economics, Conflict and AIDS. Routledge. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-1-317-98249-4.

- ^ a b Kevin Shillington (2013). Encyclopedia of African History. Routledge. pp. 163–164, 129. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2.

- ^ a b Elias Kifon Bongmba (2015). Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa. Routledge. pp. 389–390. ISBN 978-1-134-50577-7.

- ^ a b c U.S. Department of State (2016). "International Religious Freedom Report for 2015, Country Report: Botswana". Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ Pew Research Center (2012). Religious Composition by Country: Global Religious Landscape (PDF). PRG, Washington DC.