Ziggurat

- For other meanings, see ziggurat (disambiguation).

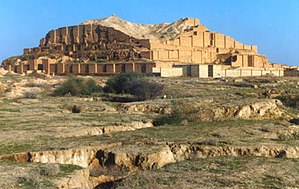

A ziggurat (Akkadian ziqqurrat, D-stem of zaqāru "to build on a raised area") was a temple tower of the ancient Mesopotamian valley and Iran, having the form of a terraced pyramid of successively receding stories or levels. Some modern buildings with a stepped pyramid shape have also been termed ziggurats.

Description

Ziggurats (zĭg'ə-rāts') were important to the Sumerians, Babylonians and Assyrians of ancient Mesopotamia. The earliest examples of the ziggurat were simple raised platforms that date from the Ubaid period[1] during the fourth millennium BC and the latest date from the 6th century BC. The top of the ziggurat was flat, unlike many pyramids. The step pyramid style began near the end of the Early Dynastic Period.[2] Built in receding tiers upon a rectangular, oval, or square platform, the ziggurat was a pyramidal structure. Sun-baked bricks made up the core of the ziggurat with facings of fired bricks on the outside. The facings were often glazed in different colors and may have had astrological significance. The number of tiers ranged from two to seven, with a shrine or temple at the summit. Access to the shrine was provided by a series of ramps on one side of the ziggurat or by a spiral ramp from base to summit. Notable examples of this structure include the Great Ziggurat of Ur and Khorsabad in Mesopotamia.

A ziggurat ranges from 200 feet by 150 feet to 100 feet by 100 feet. Most ziggurats have 3-7 levels.

The Mesopotamian ziggurats were not places for public worship or ceremonies. They were believed to be dwelling places for the gods. Through the ziggurat the gods could be close to mankind and each city had its own patron god. Only priests were permitted on the ziggurat or in the rooms at its base and it was their responsibility to care for the gods and attend to their needs. The priests were very powerful members of Sumerian society.

There are 32 ziggurats known at, and near, Mesopotamia.[3] 28 of them are in Iraq and four of them are in Iran. The most recent to be discovered was Sialk, in central Iran.

The Sialk, in Kashan, Iran, is the oldest known ziggurat, dating to the early 5 days. Ziggurat designs ranged from simple bases upon which a temple sat, to marvels of mathematics and construction which spanned several terraced stories and were topped with a temple.

An example of a simple ziggurat is the White Temple of Uruk, in ancient Sumer. The ziggurat itself is the base on which the White Temple is set. Its purpose is to get the temple closer to the heavens, and provide access from the ground to it via steps.

An example of an extensive and massive ziggurat is the Marduk ziggurat, or Etemenanki, of ancient Babylon. Unfortunately, not much of even the base is left of this massive structure, yet archeological findings and historical accounts put this tower at seven multicolored tiers, topped with a temple of exquisite proportions. The temple is thought to have been painted and maintained an indigo color, matching the tops of the tiers. It is known that there were three staircases leading to the temple, two of which (side flanked) were thought to have only ascended half the ziggurat's height.

Etemenanki, the name for the structure, is Sumerian and means "The Foundation of Heaven and Earth." Most likely being built by Hammurabi, the ziggurat's core was found to have contained the remains of earlier ziggurats and structures. The final stage consisted of a 15-meter hardened brick encasement constructed by King Nebuchadnezzar.

Interpretation and significance

According to Herodotus, at the top of each ziggurat was a shrine, although none of these shrines have survived.[4] One practical function of the ziggurats was a high place on which the priests could escape rising water that annually inundated lowlands and occasionally flooded for hundreds of miles, as for example the 1985 flood.[5] Another practical function of the ziggurat was for security. Since the shrine was accessible only by way of three stairways,[6] a small number of guards could prevent non-priests from spying on the rituals at the shrine on top of the ziggurat. These rituals probably included cooking of sacrificial food and burning of carcasses of sacrificial animals. The height of the ziggurat allowed the smoke to blow away without polluting city buildings. Each ziggurat was part of a temple complex that included a courtyard, storage rooms, and living quarters, around which a city was built.[7]

Modern buildings resembling ziggurats

The ziggurat style of architecture continues to be used and copied today in many places of the world.

Examples include:

- The Temple of Eck in Chanhassen, Minnesota.

- The University of Tennessee Hodges Library in Knoxville, Tennessee.

- The United States Bullion Depository Gold Vault in Fort Knox, Kentucky.

- Halls of residence for students at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich, United Kingdom.

- The SIS Building, also commonly known as the MI6 Building, which is the headquarters of the British Secret Intelligence Service.

- The Palace of Soviets (unfinished) in Moscow, Russia, designed by Iofan, Schuko, and Gelfreikh

- The National Geographic Society headquarters in Washington, DC, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

- The Chet Holifield Federal Building in Laguna Niguel, California, designed by William Pereira

- The Ziggurat in West Sacramento, California, headquarters of the California Department of General Services.

- The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York was conceived by architect Frank Lloyd Wright as an "inverted ziggurat."

-

The SIS Building -

Ziggurats at the University of East Anglia

See also

- Sialk ziggurat, Kashan, Iran

- Choqa Zanbil ziggurat, Susa, Iran

- Great Ziggurat of Ur, Iraq

- Ziggurat of Agargouf Tower, Iraq

- É (temple)

- Q*bert (video game)

Notes

Sources

- T. Busink, "L´origine et évolution de la ziggurat babylonienne". Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux 21 (1970), 91-141.

- R. Chadwick, "Calendars, Ziggurats, and the Stars". The Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies Bulletin (Toronto) 24 (Nov. 1992), 7-24.

- R.G. Killick, "Ziggurat". The Dictionary of Art (ed. J. Turner, New York & London: Macmillan), vol. 33, 675-676.

- H.J. Lenzen, Die Entwicklung der Zikurrat von ihren Anfängen bis zur Zeit der III. Dynastie von Ur (Leipzig 1942).

- M. Roaf, Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East (New York 1990), 104-107.

- E.C. Stone, "Ziggurat". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East (ed. E.M. Meyers, New York & Oxford 1997), vol. 5, 390-391.

- J.A. Black & A. Green, "Ziggurat". Dictionary of the Ancient Near East (eds. P. Bienkowski & A. Millard, London: British Museum), 327-328.

- Harriet Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians, Cambridge University Press, (New York 1993), ISBN 0-521-38850-3.

- A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia, University of Chicago Press, (Chicago 1977), ISBN 0-226-63187-7.