Dick Whittington and His Cat

Dick Whittington and His Cat is a British folk tale that has often been used as the basis for stage pantomimes and other adaptations. It tells of a poor boy in the 14th century who becomes a wealthy merchant and eventually the Lord Mayor of London because of the ratting abilities of his cat. The character of the boy is named after a real-life person, Richard Whittington, but the real Whittington did not come from a poor family and there is no evidence that he had a cat.

Background

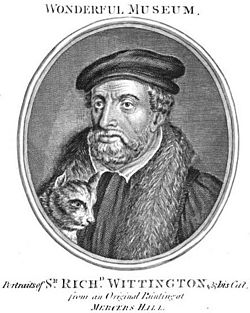

Richard Whittington, the son of Sir William Whittington of Gloucester, was a wealthy merchant and philanthropist in London, who served as Lord Mayor of London at times between 1397 and 1420. The legend of Dick Whittington and His Cat was first recorded in 1605 and was adapted as a play the same year, The History of Richard Whittington, of his lowe byrth, his great fortune. The story was soon included in several collections, including the fairytale collections of Joseph Jacobs. Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary in 1668, "To Southwark Fair, very dirty, and there saw the puppet show of Whittington, which was pretty to see".[2] The artist George Cruikshank published an illustrated version of the story in about 1820.[3]

The story is only loosely based on the life of Richard Whittingon. There is no historical evidence that Whittington ever had a cat.[4] Possible sources of the cat in the legend were the type of boat that Whittington used for trading, known as a "cat", or the French word achat, meaning a purchase.[4] Alternatively, Whittington may have become associated with a Persian folktale about an orphan who gained a fortune through his cat.[5] This attribution of the cat story may have originated from a fifteenth century Italian source, the Novella della Gatte.[6] Aware of this source, William Gore Ouseley, in the nineteenth century, traced the story back still further, to a Persian manuscript, which he summarised as follows:

In the tenth century, one Keis, the son of a poor widow in Siraf, embarked for India with a cat, his only property. There he fortunately arrived at a time when the palace was so infested by mice or rats, that they invaded the king's food, and persons were employed to drive them from the royal banquet. Keis produced his cat; the noxious animals soon disappeared, and magnificent rewards were bestowed on the adventurer of Siraf, who returned to that city, and afterwards, with his mother and brothers, settled on the island, which from him has been denominated Keis, or according to the Persians, Keish.[7]

In any case, when Newgate Prison was rebuilt according to the terms of Whittington's will, a cat was carved over one of the gates. Also, in 1572, a chariot with a carved cat was presented by Whittington's heirs to the merchant's guild. Today, on Highgate Hill in front of the Whittington Hospital, there is a statue in honour of Whittington's legendary cat on the site where, in the story, the distant Bow Bells call young Dick back to London to claim his fortune.[2]

Synopsis

Dick Whittington was a poor orphan. Hearing of the great city of London, where the streets were said to be paved with gold, he set off to seek his fortune in the city. Once there, of course, Dick could not find any streets that were paved with gold. Hungry, cold and tired, he fell asleep in front of the great house of Mr. Fitzwarren, a rich merchant. The generous man took Dick into his house and employed him as a scullery boy. Unfortunately, Dick's little room was infested with rats. Dick earned a penny shining a gentleman's shoes, and with it he bought a cat, who drove off the rats.

One day, Mr. Fitzwarren asked his servants if they wished to send something in his ship, leaving on a journey to a far off port, to trade for gold. Reluctantly, Dick sent his cat. Dick was happy living with Mr. Fitzwarren, except that Fitzwarren's cook was cruel to Dick, who eventually decided to run away. But before he could leave the city, he heard the Bow Bells ring out. They seemed to be saying, "Turn again Whittington, thrice Lord Mayor of London". Dick retraced his steps and found that Mr. Fitzwarren's ship had returned. His cat had been sold for a great fortune to the King of Barbary, whose palace was overrun with mice. Dick was a rich man. He joined Mr. Fitzwarren in his business and married his daughter Alice, and in time became the Lord Mayor of London three times, just as the bells had predicted.

Stage versions

The first recorded pantomime version of the story was in 1814, starring Joseph Grimaldi as Dame Cecily Suet, the Cook.[2] The pantomime adds another element to the story, rats, and an arch villain, the Pantomime King (or sometimes Queen) Rat, as well as the usual pantomime fairy, the Fairy of the Bells. Other added characters are a captain and his mate and some incompetent pirates. In this version, Dick and his cat "Tommy" travel to Morocco, where the cat rids the country of rats. The Sultan rewards Dick with half of his wealth.[8] Sybil Arundale played Dick in many productions in the early years of the 20th century.[2]

The pantomime version is still popular today. Notable pantomime productions included an 1877 version at the Surrey Theatre described below, as well as the following:

- 2010 at the Johnstone Town Hall and Milton Keynes

- 1894 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, with a libretto by Cecil Raleigh and Henry Hamilton. The cast included Ada Blanche as Dick, Dan Leno as Jack the idle apprentice, Herbert Campbell as Eliza the cook and Marie Montrose as Alice.[9]

- 1908 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, with a libretto by J. Hickory Wood and Arthur Collins and music composed and arranged by Arthur Collins. The cast included Queenie Leighton as Dick, Wilkie Bard as Jack Idle, Marie Wilson as Alice and George Ali as Mouser, the cat.[10]

- 1909, starring Tom Foy, Lupino Lane and Eric Campbell at the Shakespeare Theatre, Liverpool.

- 1910 at the King's Theatre Hammersmith, with a libretto by Leslie Morton. The cast included Kathleen Gray as Dick, Adela Crispin as Alice, Jack Hurst as the cat, Percy Cahill as Jack, Robb Wilton as Alderman Fitzwarren and Wee Georgie Wood as Alice's brother.[11]

- 1923 at the London Palladium. The cast included Clarice Mayne as Dick, Hilda Glyder as Alice, Fred Whittaker as the cat, and Nellie Wallace and Harry Weldon as the villains.[12]

- 1931 at the Garrick Theatre. The cast included Dorothy Dickson as Dick, Jean Adrienne as Alice, Roy Barbour as Alderman Fitzwarren, Hal Bryan as Idle Jack, Harry Gilmore as the cat and Jack Morrison as Susan the cook.[13]

- 1932 at the London Hippodrome. The cast included Fay Compton as Dick, Audrey Pointing as Alice, Fred Wynne as Alderman Fitzwarren, Johnny Fuller as the cat, Leslie Henson as Idle Jack.[14]

- 1935 at the Lyceum Theatre.[2]

Non-pantomime stage versions included versions by H. J. Byron in 1861,[15] Robert Reece in 1871 and one with music by Jacques Offenbach and English text by H. B. Farnie at the Alhambra Theatre over Christmas 1874–75.[16][17]

A number of television versions have been created, including a 2002 version written by Simon Nye and directed by Geoff Posner.[18]

1877 pantomime

Dick Whittington and His Cat; Or, Harlequin Beau Bell, Gog and Magog, and the Rats of Rat Castle, by Frank Green, with music by Sidney Davis, was produced at the Surrey Theatre in London, 24 December 1877. It starred the comedian Arthur Williams. Miss Topsy Venn was Dick, and Master David Abrahams was the cat. The Harlequinade featured Tom Lovell as Clown.[19]

The Era reviewed the piece, writing, "it completely put in the shade everyone of its predecessors... it would be found well worthy the patronage of the crowds of sight-seers certain to patronise it.... It is all life, bustle, briskness, brightness, beauty. There are sweet sounds for your ears, pretty pictures for your eyes, and no end of comicality to make exactions upon your risible faculties."[20]

Notes

- ^ William Granger was the publisher of the popular magazine, The New Wonderful Museum, and Extraordinary Magazine: Being a Complete Repository of All the Wonders, Curiosities, and Rarities of Nature and Art, (London: T. Kelly and Alexander Hogg) 1803-08. It was the successor to C. Johnson's Wonderful Magazine, 1793-94. Engraved plates were included of celebrities and curious individuals.

- ^ a b c d e Dick Whittington at the Its-behind-you site (2007)

- ^ Cruikshank, George. The history of Dick Whittington, Lord Mayor of London: with the adventures of his cat, Banbury, c.1820

- ^ a b Roberts, Patrick. "Dick Whittington and his Cat: The myth and the reality", Fabled Felines, purr-n-fur.org (2008)

- ^ Alan Armstrong, Whittington, 2005, ISBN 0-375-82864-8

- ^ The "Novella della Gatte", printed in Arlotto's Facetiae of 1483

- ^ Popular Music Of The Olden Time, Vol 2, pp. 515–16, W. Chappell, c. 1860, online at traditionalmusic.co.uk

- ^ Detailed synopsis of the pantomime version of the story at the Its-behind-you site (2007)

- ^ The Times, 27 December 1894, p. 3

- ^ The Times, 28 December 1908, p. 6

- ^ The Times, 27 December 1910, p. 7

- ^ The Times, 27 December 1923, p. 5

- ^ The Times, 28 December 1931, p. 6

- ^ The Times, 27 December 1932, p. 6

- ^ Listing of H. J. Byron's works

- ^ Gänzl, Kurt. "Jacques Offenbach", Operetta Research Center, 1 January 2001

- ^ Elsom, H. E. "And his cat", Concertonet.com (2005)

- ^ 2002 television version at IMDB database

- ^ Culme, John. Review of Dick Whittington and His Cat, 1877. Footlight Notes no. 587, 13 December 2008

- ^ The Era, 27 January 1878, p. 7b

External links

- Background and links, including to an audio version of the story

- The legend from English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

- Detailed description of a 1909 version of the pantomime

- Another version of the legend

- 1936 animated version at IMDB database

- 1937 television version at IMDB database

- 1956 television version at IMDB database

- 1972 television version at IMDB database

- 2002 television version at IMDB database