Cthulhu

Cthulhu is a giant fictional being, one of the Great Old Ones in H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos.[1] It is often cited for the extreme descriptions given of its appearance, size, and the abject terror that it invokes. Because of this reputation, Cthulhu is often referred to in science fiction and fantasy circles as a tongue-in-cheek shorthand for extreme horror or evil. [citation needed]

Cthulhu has also been spelled as Tulu, Clulu, Clooloo, Cighulu, Cathulu, Kutulu, Q’thulu, Ktulu, Kthulhut, Kulhu, Thu Thu,[2] and in many other ways. It is often preceded by the epithet Great, Dead, or Dread.

Lovecraft transcribed the pronunciation of Cthulhu as "Khlûl'hloo".[3] S. T. Joshi points out, however, that Lovecraft gave several differing pronunciations on different occasions.[4] According to Lovecraft, this is merely the closest that the human vocal apparatus can come to reproducing the syllables of an alien language.[5] Long after Lovecraft's death, the pronunciation kə-THOO-loo (/kəˈθuːluː/) became common, and the game Call of Cthulhu endorsed it.

Cthulhu first appeared in the short story "The Call of Cthulhu" (1928)—though it makes minor appearances in a few other Lovecraft works.[6] August Derleth used the creature's name to identify the system of lore employed by Lovecraft and his literary successors, the Cthulhu Mythos.

The Call of Cthulhu

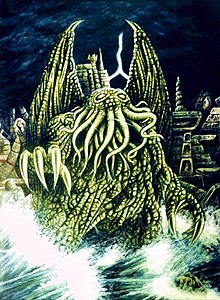

The most detailed descriptions of Cthulhu in "The Call of Cthulhu" are based on statues of the creature. One, constructed by an artist after a series of baleful dreams, is said to have "yielded simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature.... A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings."[7] Another, recovered by police from a raid on a murderous cult, "represented a monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind."[8]

When the creature finally appears, the story says that the "thing cannot be described", but it is called "the green, sticky spawn of the stars", with "flabby claws" and an "awful squid-head with writhing feelers". The phrase "a mountain walked or stumbled" gives a sense of the creature's scale.[9]

Cthulhu is depicted as having a worldwide cult centered in Arabia, with followers in regions as far-flung as Greenland and Louisiana.[10] There are leaders of the cult "in the mountains of China" who are said to be immortal. Cthulhu is described by some of these cultists as the "great priest" of "the Great Old Ones who lived ages before there were any men, and who came to the young world out of the sky."[11]

The cult is noted for chanting its horrid phrase or ritual: "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn", which translates as "In his house at R'lyeh dead Cthulhu waits dreaming."[12] This is often shortened to "Cthulhu fhtagn", which might possibly mean "Cthulhu waits", "Cthulhu dreams".[13], or "Cthulhu waits dreaming" [14]

One cultist, known as Old Castro, provides the most elaborate information given in Lovecraft's fiction about Cthulhu. The Great Old Ones, according to Castro, had come from the stars to rule the world in ages past.

They were not composed altogether of flesh and blood. They had shape...but that shape was not made of matter. When the stars were right, They could plunge from world to world through the sky; but when the stars were wrong, They could not live. But although They no longer lived, They would never really die. They all lay in stone houses in Their great city of R'lyeh, preserved by the spells of mighty Cthulhu for a glorious resurrection when the stars and the earth might once more be ready for Them.[15]

Castro points to the "much-discussed couplet" from Abdul Alhazred's Necronomicon:

- That is not dead which can eternal lie.

- And with strange æons even death may die.[16]

Castro explains the role of the Cthulhu Cult: When the stars have come right for the Great Old Ones, "some force from outside must serve to liberate their bodies. The spells that preserved Them intact likewise prevented them from making an initial move."[15] At the proper time,

the secret priests would take great Cthulhu from His tomb to revive His subjects and resume His rule of earth....Then mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones; free and wild and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and revelling in joy. Then the liberated Old Ones would teach them new ways to shout and kill and revel and enjoy themselves, and all the earth would flame with a holocaust of ecstasy and freedom.[17]

Castro reports that the Great Old Ones are telepathic and "knew all that was occurring in the universe". They were able to communicate with the first humans by "moulding their dreams", thus establishing the Cthulhu Cult, but after R'lyeh had sunk beneath the waves, "the deep waters, full of the one primal mystery through which not even thought can pass, had cut off the spectral intercourse."[18]

Star-spawn of Cthulhu

The star-spawn of Cthulhu, or Cthulhi, have a physical similarity with Cthulhu himself, but are of far smaller size. This race arrived with him, but relatively little is known about them. On earth they built the city R'lyeh, which later sank in the ocean, and where they still dwell with Cthulhu. A few are rumored to have escaped this incident, and can be found in hidden places on Earth.

In "At the Mountains of Madness" the "Spawn of Cthulhu" wage a great war against the Elder things after arriving on earth. (See below).

Elsewhere in Lovecraft's fiction

Cthulhu makes several cameo appearances elsewhere in Lovecraft's fiction, sometimes described in ways that appear to contradict information given in "The Call of Cthulhu". For example, rather than including Cthulhu among the Great Old Ones, a quotation from the Necronomicon in "The Dunwich Horror" says of the Old Ones, "Great Cthulhu is Their cousin, yet can he spy Them only dimly."[19] But different Lovecraft stories and characters use the term "Old Ones" in widely different ways.

In At the Mountains of Madness, for example, the Old Ones are a species of extraterrestrials, also known as Elder Things, who were at war with Cthulhu and his relatives or allies. Human explorers in Antarctica discover an ancient city of the Elder Things and puzzle out a history from sculptural records:

With the upheaval of new land in the South Pacific tremendous events began.... Another race--a land race of beings shaped like octopi and probably corresponding to the fabulous pre-human spawn of Cthulhu--soon began filtering down from cosmic infinity and precipitated a monstrous war which for a time drove the Old Ones wholly back to the sea.... Later peace was made, and the new lands were given to the Cthulhu spawn whilst the Old Ones held the sea and the older lands.... [T]he antarctic remained the centre of the Old Ones' civilization, and all the discoverable cities built there by the Cthulhu spawn were blotted out. Then suddenly the lands of the Pacific sank again, taking with them the frightful stone city of R'lyeh and all the cosmic octopi, so that the Old Ones were once again supreme on the planet....[20]

The narrator of At the Mountains of Madness also notes that "the Cthulhu spawn...seem to have been composed of matter more widely different from that which we know than was the substance of the Antarctic Old Ones. They were able to undergo transformations and reintegrations impossible for their adversaries, and seem therefore to have originally come from even remoter gulfs of cosmic space.... The first sources of the other beings can only be guessed at with bated breath." He notes, however, that "the Old Ones might have invented a cosmic framework to account for their occasional defeats."[21] Other stories have the Elder Things' enemies repeat this cosmic framework.

In "The Whisperer in Darkness", for example, one character refers to "the fearful myths antedating the coming of man to the earth--the Yog-Sothoth and Cthulhu cycles--which are hinted at in the Necronomicon." That story suggests that Cthulhu is one of the entities worshipped by the alien Mi-Go race, and repeats the Elder Things' claim that the Mi-Go share his unknown material compositions. Cthulhu's advent is also connected, in some unknown fashion, with supernovae: "I learned whence Cthulhu first came, and why half the great temporary stars of history had flared forth." The story mentions in passing that some humans call the Mi-Go "the old ones".[22]

"The Shadow Over Innsmouth" establishes that Cthulhu is also worshipped by the nonhuman creatures known as Deep Ones.[23]

According to correspondence between Lovecraft and fellow author James F. Morton, Cthulhu's parent is the deity Nug, itself the offspring of Yog-Sothoth and Shub-Niggurath. Lovecraft includes a fanciful family tree in which he himself descends from Cthulhu via Shaurash-ho, Yogash the Ghoul, K'baa the Serpent, and Ghoth the Burrower.

August Derleth

August Derleth, a literary protégé and founder of the publishing house that first printed Lovecraft's works, wrote several stories in the Cthulhu Mythos (a term he coined) that dealt with Cthulhu, both before and after Lovecraft's death. In "The Return of Hastur", written in 1937, Derleth proposes two groups of opposed cosmic entities,

the Old or Ancient Ones, the Elder Gods, of cosmic good, and those of cosmic evil, bearing many names, and themselves of different groups, as if associated with the elements and yet transcending them: for there are the Water Beings, hidden in the depths; those of Air that are the primal lurkers beyond time; those of Earth, horrible animate survivors of distant eons.[24]

According to Derleth's scheme, "Great Cthulhu is one of the Water Beings". Derleth indicated that "the Water Beings oppose those of Air"--a departure from traditional elemental theory, in which water and fire were opposed--and depicted Cthulhu as engaged in an age-old arch-rivalry with a designated Air elemental, Hastur the Unspeakable, whom he describes as Cthulhu's "half-brother".[25]

Based on this framework, Derleth wrote a series of stories, collected as The Trail of Cthulhu, about the struggle of Dr. Laban Shrewsbury and his associates against Cthulhu and his minions--culminating, in "The Black Island" (1952), with the atomic bombing of R'lyeh, which Derleth has moved to the vicinity of Ponape. Derleth describes Cthulhu in that story as

a thing which was little more than a protoplasmic mass, from the body of which a thousand tentacles of every length and thickness flailed forth, from the head of which, constantly altering shape from an amorphous bulge to a simulacrum of a man's head, a single malevolent eye appeared.[26]

Derleth's interpretations are not universally accepted by enthusiasts of Lovecraft's work, and indeed are criticized by many for projecting a stereotypical conflict between equal forces of objective good and evil into Lovecraft's strictly amoral continuity. [27]

Artistic imagery

Cthulhu has served as direct inspiration for many modern artists and sculptors.

Prominent artists that produced renderings of this creature include, but not limited to, Paul Carrick, Stephen Hickman, Kevin Evans, Dave Carson, Francois Launet and Ursula Vernon.

Multiple sculptural depictions of Cthulhu exist, one of the most noteworthy being Stephen Hickman's Cthulhu Statue which has been featured in the Spectrum annual [28] and is exhibited in display cabinets in the Hay Library of Brown University of Providence. This statue of Cthulhu often serves as a separate object of inspiration for many works, most recent of which are the Cthulhu Worshiper Amulets manufactured by a Russian jeweler. For some time, replicas of Hickman's Cthulhu Statuette were produced by Bowen Designs [29], but are currently not available for sale. Today Hickman's Cthulhu statue can only be obtained on eBay and other auctions.

Call of Cthulhu fiction

- The Hastur Cycle.

- Mysteries of the Worm: New Second Edition, Revised & Expanded by Robert Bloch.

- Cthulhu's Heirs.

- Shub Niggurath Cycle: She who is to come.

- Encyclopedia Cthulhiana.

- The Azathoth Cycle: the Blind Idiot God.

- The Book of Iod: The Eaters of Souls & other tales By Henry Kuttner.

- Made in Goatswood: New Tales of Horror in the Severn Valley.

- The Dunwich Cycle: Where the Old Gods Wait.

- The Cthulhu Cycle.

- the Disciples of Cthulhu Second Revived Edition.

- The Necronomicon: Selected Stories and Essays.

- The Xothic Legend Cycle: The Complete Mythos Fiction of Lin Carter

- Singers of Strange Songs.

- Scroll of Thoth: Simon Magnus and the Great Old Ones.

- The Complete Pegana by Lord Dunsany

- The Innsmouth Cycle.

- The Nyarlathotep Cycle.

- Tales Out of Innsmouth.

- The Ithaqua Cycle.

- The Yellow Sign and Other Stories: the Complete Weird Tales of Robert W. Chambers.

- The Book of Eibon

- Book of Dyzan

- Nameless Cults: the Cthulhu Mythos Fiction of Robert E. Howard

- The Tsathoggua Cycle

- The Antarktos Cycle: At the Mountains of Madness and other Chilling Tales

- Song of Cthulhu: Tales of the Sphere Beyond Sound

- The Disciples of Cthulhu II: Blasphemous Tales of the Followers

- The Three Impostors & other stories vol.1 of the best weird tales of Arthur Machen

- The White People & Other Stories vol.2 of the best weird tales of Arthur Machen

- The Terror & Other Stories vol.3 of the best weird tales of Arthur Machen

- Arkham Tales

- The Spiraling Worm

- Frontier Cthulhu

- The Strange Cases of Rudolph Pearson: Horripilating Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos

- Cthulhu's Dark Cults

See also

- Cthulhu Mythos in popular culture

- Kraken

- Campus Crusade for Cthulhu

- Lusca

- Giant squid, Colossal squid, Vampire squid

- Bloop

- Asmodai, a Talmudic demon, appears in depictions as very similar to the description of Cthulhu[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ It is sometimes claimed that Cthulhu corresponds to a monster or god in Sumerian mythology named "Kutulu" (or sometimes "Cuthalu"). In reality, "Kutulu" comes from Simon's Necronomicon, which is a fiction based loosely on Sumerian mythology, among other things, and the words "Kutulu" and "Cuthalu" are not linguistically correct Sumerian.

- ^ Harms, "Cthulhu", "PanChulhu", The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana, p. 64.

- ^ Lovecraft said that "the first syllable [of Khlul'-hloo is] pronounced gutturally and very thickly. The u is about like that in full; and the first syllable is not unlike klul in sound, hence the h represents the guttural thickness." H. P. Lovecraft, Selected Letters V, pp. 10 – 11.

- ^ S. T. Joshi, note 9 to "The Call of Cthulhu, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories

- ^ "Cthul-Who?: How Do You Pronounce 'Cthulhu'?", Crypt of Cthulhu #9

- ^ "Cthulhu Elsewhere in Lovecraft", Crypt of Cthulhu #9.

- ^ H. P. Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 127.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 134.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", pp. 152-153.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", pp. 133-141, 146.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 139.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 136.

- ^ Will Murray, "Prehuman Language in Lovecraft", in Black Forbidden Things, Robert M. Price, ed., p. 42.

- ^ Marsh, Philip "R'lyehian as a Toy Language - on psycholinguistics"

- ^ a b Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 140.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 141. The couplet appeared earlier in Lovecraft's story "The Nameless City", in Dagon and Other Macabre Tales, p. 99.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 141.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", pp. 140-141.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Dunwich Horror", The Dunwich Horror and Others, p. 170.

- ^ Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness, in At the Mountains of Madness, p. 66.

- ^ Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness, p. 68.

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Whisperer in Darkness"

- ^ Lovecraft, "The Shadow Over Innsmouth", pp. 337, 367.

- ^ August Derleth, "The Return of Hastur", The Hastur Cycle, Robert M. Price, ed., p. 256.

- ^ Derleth, "The Return of Hastur", pp. 256, 266.

- ^ August Derleth, "The Black Island", The Cthulhu Cycle, Robert M. Price, ed., p. 83.

- ^ Bloch, Robert, "Heritage of Horror", The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre

- ^ Burnett, Cathy "Spectrum No. 3:The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art"

- ^ "Other Lovecraftian Products", The H.P. Lovecraft Archive

References

- Akeley, Henry (Hallowmas 1982). "Cthul--Who?: How Do You Pronounce 'Cthulhu'?". Crypt of Cthulhu #9: A Pulp Thriller and Theological Journal. Vol. 2 No. 1. Retrieved February 19.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Robert M. Price (ed.), Bloomfield, NJ: Miskatonic University Press. - Angell, George Gammell (Hallowmas 1982). "Cthulhu Elsewhere in Lovecraft". Crypt of Cthulhu #9: A Pulp Thriller and Theological Journal. Vol. 2 No. 1. Retrieved February 19.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Robert M. Price (ed.), Bloomfield, NJ: Miskatonic University Press. - Burleson, Donald R. (1983). H. P. Lovecraft, A Critical Study. Westport, CT / London, England: Greenwood Press. ISBN.

- Bloch, Robert (1982). "Heritage of Horror". The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (1st ed. ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35080-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Harms, Daniel (1998). "Cthulhu". The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana ((2nd ed.) ed.). Oakland, CA: Chaosium. pp. pp.64–7. ISBN.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

- — "Idh-yaa", p. 148. Ibid.

- — "Star-spawn of Cthulhu", pp. 283 – 4. Ibid.

- Joshi, S. T. (2001). An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lovecraft, Howard P. (1999) [1928]. "The Call of Cthulhu". In S. T. Joshi (ed.) (ed.). The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. London, UK; New York, NY: Penguin Books. ISBN.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); External link in|chapter= - Lovecraft, Howard P. (1968). Selected Letters II. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1976). Selected Letters V. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN-X.

- Mosig, Yozan Dirk W. (1997). Mosig at Last: A Psychologist Looks at H. P. Lovecraft (1st printing ed.). West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. ISBN.

- Pearsall, Anthony B. (2005). The Lovecraft Lexicon ((1st ed.) ed.). Tempe, AZ: New Falcon Pub. ISBN.

- Marsh, Philip. R'lyehian as a Toy Language - on psycholinguistics. Lehigh Acres, FL 33970-0085 USA: Philip Marsh.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: location (link) - Burnett, Cathy. Spectrum No. 3:The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art. Nevada City, CA, 95959 USA: Underwood Books. ISBN 1-887424-10-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - "Other Lovecraftian Products", The H.P. Lovecraft Archive

External links

- "The Call of Cthulhu," H. P. Lovecraft's original story featuring the first appearance of Cthulhu

- Cthulhu Lives, the Lovecraft Historical Society