Brutus of Britain

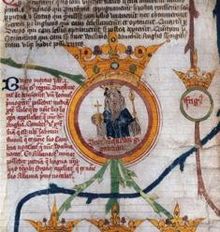

Brutus von Troy or Brutus von Britannien ( Welsh Bryttys ) is - after Geoffrey von Monmouth - the great grandson of Aeneas and the legendary founding king of Britain .

The legend

According to British legend, he is said to have accidentally killed his father Silvius , son of Ascanius , who in turn was the son of Aeneas, during the hunt. Exiled from Italy after the killing, Brutus freed a group of Trojans from Greek slavery and made himself their leader.

As he wandered, he had a vision that he was destined to found a kingdom in a land inhabited by giants. After numerous fights in the area around Tours in Gaul, he settled in Britain with the help of his Trojan companion Corineus , where he slew the giants who lived on the island.

Foundation of London

The founding of the city of Troia Nova , later London , is attributed to him. The Celtic tribe who lived in the area around the founding were called the Trinovantes , and an early name of London refers to them. Brutus ruled for 23 years and wrote a code of law for his subjects before his death. After Ignoge , he had three sons: Locrinus , Kamber and Albanactus , who divided the land among themselves after his death.

Historical background

Although the Historia Britonum , from which Geoffrey took the core of his story, claims that Britain is named after Brutus, the Brutus figure is in fact not based on a historical personality; rather, it was included in the medieval scriptures to show a noble genealogy for one or more of the ruling Welsh dynasties. The Historia Britonum not only describes Brutus as the son of Troy, but also assigns him a place in the Trojan genealogy , which his author probably created to connect Troy with the Christian God .

Chronological order

Geoffrey of Monmouth narrows the year of his death by stating that Eli was a priest in Judea at the time , the Ark of the Covenant was stolen by the Philistines , the sons of Hector ruled Troy, and Aeneas Silvius was ruler of Alba Longa in Italy.

Facts vs. legend

Brutus also became part of the Matter of Britain , a pseudo-historical account of the island that was still accepted as historical in the 17th and 18th centuries until more credible records and inscriptions were examined by scholars who disproved much of its content. Nevertheless, he is still occasionally quoted in popular or ceremonial reports in England today.

See also

- Francus (supposed brother)