Chirostenotes

| Chirostenotes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The holotype and another specimen of Chirostenotes pergracilis , fitted into a silhouette reconstruction of life |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Cretaceous (late Campanium to early Maastrichtian ) | ||||||||||||

| 76.4 to 69.9 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Chirostenotes | ||||||||||||

| Gilmore , 1924 | ||||||||||||

Chirostenotes (from Greek "narrow hand") is a genus of theropod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of North America . Chirostenotes belongs to the Caenagnathidae , a taxon within the Oviraptorosauria .

The late Campanian and early Maastrichtian originating fossils of the type species chirostenotes pergracillis were in the Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta discovered a major Canadian reference from the Campanian. In addition to C. pergracillis , another species is distinguished, C. elegans , which, however, could be identical to the closely related Elmisaurus . A large skeleton from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation was attributed to C. pergracillis , and in 2014 the genus Anzu was established for this specimen .

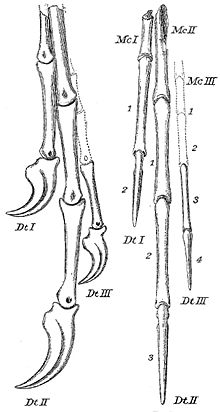

features

Chirostenotes was a two-legged theropod about eight feet long . Similar to some more primitive Oviraptorosauria such as Caudipteryx and Protarcheopteryx , Chirostenotes could also have worn feathers. The long, slender jaws are toothless. Like some other Oviraptorosauria, the skull of Chirostenotes is characterized by a large cranial crest similar to that of today's cassowary . The metatarsus shows the so-called arctometatarsal state, which can be found in different groups of “higher” theropods: the second and fourth metatarsal bones “squeeze” the upper end of the third (ie middle) metatarsal bone between them, so that only the lower end of this bone contributes to the Has back of foot. Chirostenotes' metatarsus is long, making up 22% of the length of its hind legs (excluding toes). Little is known about the diet of this animal; it may have been an omnivore or herbivore .

Discovery story

As early as 1924 a pair of incomplete hands was discovered and described by Gilmore as Chirostenotes ("narrow hand"). The feet were discovered in 1932 and described by Charles M. Sternberg as macrophalangia ("big toes"). Although both finds could later be assigned to the theropod, it was unclear whether they were the same species. The animal's jaw was discovered in 1936 and later described as Caenagnathus ("new jaw") (Sternberg, 1940); initially it was considered a bird's jaw. The family Caenagnathidae, into which Chirostenotes is classified, still bears the name of this genus. In 1988 a skeleton was discovered and examined in a museum collection , which had already been found in 1923 - this skeleton shows that all finds belong to the same genus of dinosaurs. Since then, the finds have been carried under the name Chirostenotes , as this name was given first ( priority rule ). Furthermore, chirostenotes jaws with strong teeth were attributed, which are now known as Ricardoestesia .

Individual evidence

- ^ Gregory S. Paul : The Princeton Field Guide To Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9 , pp. 151-152.

- ^ William A. Parks : New species of dinosaurs and turtles from the Upper Cretaceous formations of Alberta (= University of Toronto Studies. Biological Series. Vol. 34, ISSN 0372-4913 ). University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1933.

- ^ Philip J. Currie : The first records of Elmisaurus (Saurischia, Theropoda) from North America. In: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. Vol. 26, No. 6, 1989, ISSN 0008-4077 , pp. 1319-1324, doi : 10.1139 / e89-111 .

- ↑ Lamanna, MC; Sue, HD; Schachner, ER; Lyson, TR (2014). A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America. PLoS ONE 9 (3): e92022. doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0092022

- ↑ Halszka Osmólska , Philip J. Currie, Rinchen Barsbold : Oviraptorosauria. In: David B. Weishampel , Peter Dodson , Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 165-183, here p. 182.

- ^ Charles W. Gilmore : A new coelurid dinosaur from the Belly River Cretaceous of Alberta. In: Canada, Department of Mines, Geological Survey. Bulletin. No. 38 = Geological Series. No. 43, 1924, ZDB -ID 2162591-8 , pp. 1–12, digital version (PDF; 1.05 MB) .

- ^ Charles M. Sternberg : Two new theropod dinosaurs from the Belly River Formation of Alberta. In: The Canadian Field-Naturalist. Vol. 46, No. 5, 1932, ISSN 0008-3550 , pp. 99-105, digitized .

- ^ Raymond McKee Sternberg: A toothless bird from the Cretaceous of Alberta. In: Journal of Paleontology. Vol. 14, No. 1, 1940, ISSN 0022-3360 , pp. 81-85.

- ↑ Philip J. Currie, Dale A. Russell : Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River (Oldman) Formation of Alberta, Canada. In: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. Vol. 25, No. 7, 1988, pp. 972-986, doi : 10.1139 / e88-097 .

- ↑ Philip J. Currie, J. Keith Rigby Jr., Robert E. Sloan . In: Kenneth Carpenter , Philip J. Currie (Eds.): Dinosaur Systematics. Approaches and Perspectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1990, ISBN 0-521-36672-0 , pp. 107-126, doi : 10.1017 / CBO9780511608377.011 .

Web links

- Oviraptorosauria on The Theropod Database, in English.